3 Against Expand Supply Presumed Consent and

advertisement

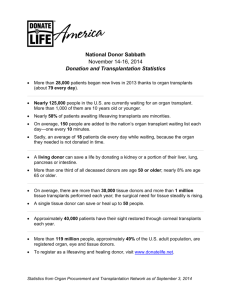

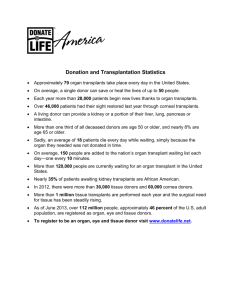

1 Don't Take Your Organs To Heaven by Margaret R. McLean "Don't take your organs to heaven. Heaven knows we need them here." Bumper sticker, Mission Concepción, San Antonio, Texas Todd Krampitz's message was simple-"I Need a Liver - Please Help Save My Life!" Plastered on two billboards along a busy Houston freeway, Todd's plea included a toll free number and web site, which told his story. Krampitz, 32, was hospitalized in May 2004 with sudden severe abdominal pain. The diagnosis was liver cancer so extensive that he would never survive the average 515 day climb to the top of the liver transplant wait list some 17,000 patients long. Seeing no other option, his family and friends skirted the national organ donor registry pleading for a directed donation, one in which a family would ask that their loved one's liver go directly to Krampitz. It worked. Within a week, a family directed that their deceased relative's liver go to Krampitz rather than to the person on the top of the list maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which coordinates the nation's transplants. Such directed donations to strangers are legal but raremost directed donations occur within families or between friends. Internetbrokered transplants raise ethical concerns about human need, the just distribution of available organs, and the formation of an international cybermarket in human organs. Organ transplants fascinate us. They are ripe with the promise of life and drenched in the mystery of otherness. In the decades since the first organ transplant, a kidney, on December 23, 1954, surgeons have successfully transplanted many vital organs-kidney, liver, lungs, heart, pancreas, intestine-and some nonvital body parts, notably hands and soon possibly faces. Improved surgical techniques, organ preservation, and tissue matching together with increasingly effective anti-rejection agents and antibiotics, have produced remarkable success. In 2004, one-year patient survival for kidney transplants was approximately 95%. For livers, it was around 80%. After 10 years, the survival rate for both drops to around 55 to 75%-the higher survivability the result of living donor transplants. Controlling chronic rejection continues to be difficult. Organ transplantation is expensive. In 2003, a kidney transplant averaged $51,000 and a liver transplant five times that. The cost of immunosuppressive agents adds thousands of dollars per year in expenses for the remainder of the patient's life. Medicare, Medicaid, and most insurance pick up some, but not all, of these costs. In addition, it costs approximately $35 billion per year to care for those patients who wait in line with end-stage organ failure. 2 The biggest challenge in transplantation is the chronic scarcity of organs. Although a record 27,000 human organs were transplanted in the United States in 2004, 6,200 patients died waiting for an organ that never camealmost 88,000 wait still. Despite 7,153 deceased donors and almost 7,000 living donors, organ donation has chronically failed to keep up with need. Each day, 106 people are added to the organ waiting list, 68 people receive a new organ, 17 people die waiting, and 27 people become organ donors, averaging 3 usable organs each. This unyielding shortage is exacerbated by the fact that many patients require multiple transplants, since after 10 years or so the transplanted organs fail due chronic rejection. Given the paucity of transplantable organs, we face two vexing questions: How should we distribute the organs that are currently available-to the sickest, to the one waiting longest, to the highest bidder? And, how can the supply be increased? The ELCA addressed this "acute shortage" in its 2004 policy resolution on The Donation of Organs, Tissue, and Whole Blood. Here, organ donation is considered "an act of stewardship" and "an expression of sacrificial love for a neighbor." The statement calls on the government to prohibit coercion, to outlaw the buying and selling of organs, and to assure "efficient, equitable access" to organs, tissues, and blood. It calls for closing the gap between medical need and organ availability in ways that do not involve payment. Finally, it seeks careful deliberation and assessment of a shift in the default position from "no one is a donor unless otherwise indicated" to "everyone is a donor unless otherwise indicated" and of the purported promise of xenotransplantation. Todd Krampitz's successful media campaign raised concerns about the bypassing of the established organ allocation system. The American Medical Association preaches that the distribution of any scarce medical resource should be rooted in ethically justified criteria such as likely benefit to the patient and the extent of need-the same triage criteria used in over-taxed military field hospitals and over-crowded emergency rooms. In November 2004, UNOS adopted a position statement opposing public solicitation of organs from dying or deceased donors for a transplant candidate when no familial or personal tie exists. The concern is for putting the needs of one advertising-savvy candidate above those of others whose condition may be more acute or long-term survival more assured, or who lack the wherewithal to rent billboards or navigate the Internet. Certainly, public trust in the fairness of organ allocation is threatened by such private solicitation. There is the fear that in private negotiations, money may change hands. Justice and equity may be compromised when "the market" rather than altruism directs organ donation. Even so, who of us would not launch a website or pay for a billboard to save a life? The ELCA statement urges careful deliberation about replacing our policy of "presumed refusal" with "presumed consent" under which we all would be 3 presumed to be organ donors unless we specified otherwise or our family objected. However, being required to provide tissues and organs so that others might live flies in the face of our strong cultural concern for individual autonomy and bodily integrity, even after death. Whether or not "presumed consent" would result in an increased organ supply is the subject of much debate with evidence from Europe that it may have little impact on the supply chain. Effective or not, presumed consent is a giant step away from our current reliance on altruistic donation, which appeals to our best selves in making a donated organ a gift rather than an obligation or transaction. Such gift-giving embodies compassion and affirms our solidarity with others. Perhaps, in a world of infinite resources and unbounded justice, gift-giving would be enough. However, what do we do in this imperfect world where there are not enough resources to meet human need? The focus on the organ as gift turns a blind eye to the fact that once the gift has been given money enters the process-surgeons are paid; hospitals are paid; why not living donors or deceased donors' families? Perhaps living donors-especially the poor-would be coerced into accepting a great risk for a pittance. However, cadaveric donations put no one at risk and perhaps families would be more willing to donate if compensated. Because many patients die before a needed organ becomes available, there has been increasing interest in living donors, many of them unrelated to the recipient. Living donors are sought for liver, kidney, pancreas, and small bowel transplantation. However, asking someone to donate an organ that is currently in use raises a raft of ethical questions-the most striking one being how can one justify exposing healthy individuals to the risk of major surgery and loss of an organ, or a slice of an organ, solely to benefit another? How does one weigh the tangible health risk to the donor with the intangibles of heroism, compassion, and gratitude that come with saving a life? In the context of such desperate need, is free and informed consent of the donor ever possible? And, if consent is possible, how is medicine's responsibility to do no harm fulfilled? Many of us have had to weigh the risks and benefits of surgery. Cardiac bypass surgery saves lives, and the risk of life-threatening complications and death is worth it for many. However, being a living donor puts an otherwise healthy person at risk solely to benefit another. Surely, there is strong ethical impetus to protect the health and well-being of living donors, to be certain that they understand not only the surgical risks but also personal, financial, and insurance implications of their decision. As there are no direct health benefits to the donor, a true balance between risks and benefits for both the donor and the recipient is required. Ethicists worry about situations in which benefit accrues to one person or group at the expense of another. Recognizing the real danger faced by living donors, true balance may involve providing them with catastrophic life and health insurance policies. Even so, at times, despite the compelling need and a willing donor, such sacrifice would simply be wrong-such as when the recipient has a poor chance of long term survival. 4 Organ scarcity is forcing us to look to animals for help. Xenotransplantation is the transplantation of cells, tissues, or organs from one species to another, from animals to humans for example. Pigs are the most promising "donors" for human organ transplants since they can be genetically modified relatively easily-a necessity if rejection is to be avoided-and have similar anatomical structure to humans. As deep as the need for transplantable organs is and as promising as recent pig studies are, there is a major ethical concern-the trade-off between benefit to individual patients and risk of infection of the general population with animal viruses. All pigs harbor porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) that might infect organ recipients with possibly deadly results. Bird flu is a current reminder of the proclivity of animal viruses to jump to humans. Notably, this threat would be to the public, not solely to an individual, since animal viruses can reprogram themselves to jump from person to person bypassing the need for an animal host. HIV is a powerful case in point. We must weigh desperate individual need against the potentially grave, but unknown, risk of public infection. The model of the autonomous patient making an informed decision does not help, as this is not a risk taken solely by the patient. It is a public risk that requires public consideration and attention to the common good. At the very least, clinical trials ought not be undertaken unless and until the viral threat is thwarted. As the very public dying of Terri Schiavo so painfully reminded us, we need to tell our loved ones of our wishes about end-of-life care including organ donation. Moreover, we need not interfere in the fulfilling of our loved ones' wishes to be a donor. Our families need to know and be supportive, as Todd Krampitz's family knew and was supportive, of our desire to be an organ donor. When Todd Krampitz died on April 20, 2005, he became a donor himself, leaving his corneas so others could see again. McLean is the director of biotechnology and health care ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics and a Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies at Santa Clara University. This article was originally published in The Lutheran (Sept. 2005). Man with billboard campaign for liver dies This op-ed was published in the San Jose Mercury News on 31 January 2002 under the title, "Criminals Should Be Far Down on the Heart Transplant List." A Houston man who moved to the head of the line for a liver transplant after a much-publicized billboard campaign has died eight months after the transplant. 5 It was not clear whether Todd Krampitz, diagnosed with advanced LIVER CANCER last year, succumbed to cancer, transplant-related complications or some other cause. Family members did not return calls seeking information, but thanked supporters in a statement. "Definitely (the transplant) was the right thing to do. We gave him eight more months with his family," said Sherrill Lanthier, director of the Multiorgan Transplant Center at The Methodist Hospital where Krampitz, who died Wednesday, had his operation. "We hope his story has heightened awareness of the dire need for organ donation. While we don't condone advertising for an organ ... we feel that transplanting Todd was the right thing to do for him." The family statement noted that 32-year-old Krampitz donated his corneas "so that now another will be able to see." Krampitz's August 2004 transplant angered many waiting for organs and prompted charges that he had cut in line. Most people wait months for a liver, and many die before one is found. (In Texas, more than 1,200 people are waiting for fewer than 500 livers available in the state each year.) The controversy prompted the United Network for Organ Sharing, which oversees organ allocation, to recommend in November that hospitals discourage patients from soliciting organs, and if possible, refuse to perform such transplants. Supporters argued that the family that donated the liver to Krampitz might not have donated anything at all without the media attention generated by the billboards. Krampitz, who had a digital photography business, and his wife, Julie, whom he married just two months before being diagnosed with cancer, appeared on local television and CNN. Nationwide, patients were inspired to post their own pleas on the Internet, with mixed results. "It seems to me this tragedy of his death is a reminder of what happens when you allow people to jostle in line to gain access to transplants, it may not be the best or most effective use of this scarce resource," said Arthur Caplan, chairman of medical ethics at the University of Pennsylvania, who criticized the Krampitz transplant. "You wind up making it harder for people to trust the system is fair." Without advertising, Krampitz likely would not have gotten a transplant. In accordance with UNOS guidelines, which factor in severity of illness as well as the patient's odds of benefiting from the operation, he was low on the waiting list. That's because patients with advanced LIVER CANCER typically do not survive long even after transplantation. (Without cancer or other complications, transplant patients can hope to live out a normal lifespan.) However, UNOS guidelines contain a loophole seldom used by deceased donors. The loophole, called "directed donation," allows donor families to decide where the organs go. 6 The Krampitz billboards — which featured a smiling photo of the attractive newlywed — placed next to busy highways, and a Web site detailing his story, resulted in widespread public support. Less than a week after the signs went up along U.S. 59 at Buffalo Speedway and the Beltway, an anonymous donor family specified that the liver go to Krampitz. Stung by criticism and sensitive to how their good fortune might strike those still waiting, the Krampitz family soon stopped talking to the media. They put up another billboard, one that said, "Thank you." They urged awareness of the need for organ donors and provided updates on their Web site, www.toddneedsaliver.com. Five weeks after the transplant, Julie Krampitz reported on the Web site that Todd was driving again and gaining weight. By December, he was back at work full time. A family photo shows a slightly wan-looking Krampitz. A January update hinted of problems, with lab tests showing elevated liver enzymes. There was no mention of organ rejection, and a biopsy showed the liver was healthy. However, there was evidence of some sort of blockage in his bile duct. A February entry expressed gratitude for the donor family's generosity, but made no mention of Todd's health status. The last entry says, "On the morning of April 20, 2005, Todd went to be with his Lord and Savior. He was surrounded by his family and friends and passed away peacefully." Sharleen Bridgman of Aubrey, near Denton, was one of those angered by Krampitz's transplant. At the time, she and her husband were living in a motel near the Texas Medical Center while he waited for a liver. Today, Bobby Bridgman has returned to his former self, having gotten a transplant one month after Krampitz. Upon learning Krampitz had died, Sharleen Bridgman expressed sympathy for the family — but remained unwavering in her criticism of the way they solved the problem. "I feel like if you advertise for something, you're buying. I still feel strong today about making sure you go through the proper channels," she said. "Time was ticking away for us, too.