Different Skills? Identifying Differentially Effective Teachers of

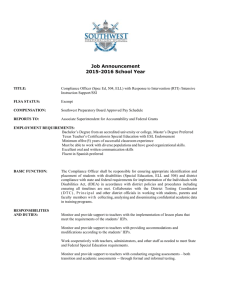

advertisement