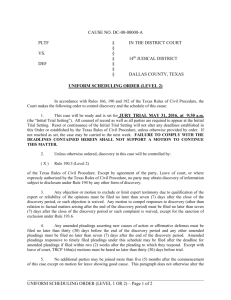

Mediation: A Revolutionary Process that is Replacing

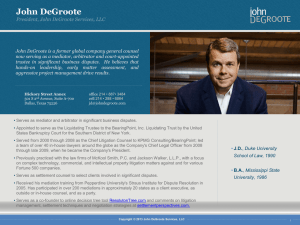

advertisement