Kathleen Springer Dr. James S. Josefson PSCI-470

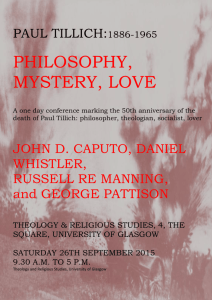

advertisement

Kathleen Springer Dr. James S. Josefson PSCI-470-01 8 December 2015 Death of God Theology Death of God theology is a branch of philosophy of religion in which theologians have wrestled with postmodern ideas within a Christian framework. The earliest figure in death of God theology is Wilhelm George Friedrich Hegel. Hegel was a philosopher well-known for his dialectics in Phenomenology of Spirit, in which consciousness progresses to freedom. With regards to the death of God, Hegel viewed this as one part of the development of consciousness. As scholar Findlay writes of this in his Hegel’s Study of the Religious Consciousness, “The descent of the abstract universal into sensuous embodiment is also, of course, the elevation of what I sensuous into what is abstract and notional: the death of God leads to His Resurrection and Ascension” (55, 1967). To Hegel, Jesus’ death, resurrection, and ascension do not represent a series of historical events but rather holds abstract meaning for a deeper understanding of consciousness. Hegel had hypothesized that God had once been a free Spirit at the beginning, but had progressed dialectically into becoming God as understood in the Old Testament (need citation). This is the thesis. Then God negated himself through Jesus, who is the antithesis. The death of God, as manifested in the death of Jesus during the crucifixion, allowed for the synthesis, the Holy Spirit (need citation). At the end, the Holy Spirit will become Absolute Spirit, which corresponds to the ultimate goal of human consciousness, which is to be reconciled with Absolute Spirit (need citation). Paul Tillich, a death of God theologian, wrestles with the framework Hegel has presented with regards to Christianity. He reject’s Hegel’s dialectics, in that the Christianity in the Bible was one part of Spirit’s progression but not Absolute Spirit. To Tillich, the thesis, Christianity, must be maintained. There is no progression of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Although Tillich recognizes that there are antitheses, he sees these as enemies of the thesis that must be removed. In the conclusion of his The Courage to Be, he writes, “It returns in terms of the absolute faith which says Yes although there is no special power that conquers guilt The courage to take the anxiety of meaninglessness upon oneself is the boundary line up to which the courage to be can go. Beyond it is mere non-being. Within it all forms of courage are re-established in the power of the God above the God of theism. The courage to be is rooted in the God who appears when God has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt” (190, 1952). This absolute faith refers to the undying conviction to maintain the thesis, which Tillich specifically identifies as “the courage to be.” Being refers to the thesis, and non-being refers to the dangerous antithesis. The anxiety of meaninglessness comes from attacks of the antithesis upon the thesis. This courage to attack the anxiety and meaningless comes from God. Tillich develops this idea of reconfirmation of the thesis through an exploration of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. According to Tillich, “Nietzsche is the most impressive and effective representation of what could be called a “philosophy of life.” Life in this term is the process in which the power of being actualizes itself. But in actualizing itself it overcomes that in life which, although belonging to life, negates life. One would call it the will which contradicts the will to power” (27, 1952). By this, Tillich explicitly demonstrated an understanding opposite to Hegel’s. While Hegel argues for a dialectical understanding of a synthesis building upon a thesis and a corresponding antithesis, Tillich does not see any progression or development of a synthesis bringing about a new thesis. Rather, Tillich argues that the thesis must be maintained despite reason. There is no “other” that negates and limits the thesis; rather, the thesis itself must look within itself and remove portions of itself that demonstrate internal inconsistency. Tillich further expresses this when he writes that “courage is the power to affirm itself in spite of this ambiguity, while the negation of life because of its negativity is an expression of cowardice” (27, 1952). So we need to affirm life. Tillich builds on Nietzsche’s ideas to a better understanding of how we should not let pity drive us to reason and instead affirm life. p. 27 has answer for p. 24: transcendence! (for self-affirmation) p. 28 “Self-affirmation is the affirmation of life and of the death which belongs to life.” Interesting “Virtue for Nietzsche as for Spinoza is self-affirmation.” To develop this idea, Tillich uses a quotation from Thus Spoke Zarathustra as follows: “And life itself confided this secret to me: ‘Behold,’ it said, “I am that which must always overcome itself.” (Then explain about Tillich “Rather would I perish than foreswear this; and verily, where there is perishing and a falling of leaves, behold, where life sacrifices itself—for power. That I must be struggle and a becoming and an end and an opposition to ends—alas, whoever guesses what is my will should also guess on what crooked paths it must proceed” (115). Here Nietzsche expresses the unpleasantness of reality, that we must struggle Furthermore, this passage can be clarified by another portion of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “God is a thought that make crooked all that is straight and makes turn whatever stands. How? Should time be gone, and all that is impermanent a mere lie? To think this is a dizzy whirl for human bones, and a vomit for the stomach; verily, I call it the turning sickness to conjecture thus. Evil I call it.” (Nietzsche 86, 1978). This quotation, taken by itself, may appear to be a negative criticism of God; however, taken within the larger context of the previous passage, it becomes apparent that God is a part of the struggle that life experiences in needing to negate itself. Evil can be understood as the need for sacrifice, from a Hegelian perspective [need citation]. This sacrifice can be seen as the sacrifice of God God’s Self. God is evil because God requires God’s own sacrifice. God is simultaneously good and evil. Because God is good, the sacrifice of God is evil. Because God requires the sacrifice of God, God is evil. This is a very interesting paradox. Nietzsche may have been developing this paradox in claiming that God is evil. God makes the straight crooked because God demands God’s sacrifice. That is rather crooked. But in doing so, God makes things real. The literal sacrifice in this exchange is God. God is sacrificed so that we may live in reality. Bonhoeffer is quite useful here. Suffering connects us to God. We must remember and identify with the Crucifixion if we are to become alive. I just noticed something interesting. Tillich wants to hold onto the thesis, and Hegel wants the synthesis, but Bonhoeffer wants the antithesis. Or rather, God is one aspect of the life’s struggle in negating itself. As Franke wrote, “Only in the temporal world can God truly live, and this entails submitting to death as well” (217, 2007). In becoming part of life as defined by the temporal world in which we live, God must submit to death. How does God become alive? Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a death of God theologian, addresses this in one of his letters from prison near the later years of his life, in which he writes, And we cannot be honest unless we recognize that we have to live in the world etsi deus non daretur [“even if there were no God”]. And this is just what we do recognize—before God! God himself compels us to recognize it. So our coming of age leads us to a true recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we must live as men who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15.34). The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world on to the cross. He is weak and powerless in this world, and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us (360, 1997). Instead of a being outside human beings, God is in the life of a Christian. Jesus on cross—it’s your responsibility to respond to the crucified Jesus. God is in suffering, we should respond to suffering, “least of these” verse, God of the law is dead, idea of a personal, magical God as the driving force of the world is dead—we have no responsibility with that kind of a God being alive. You have a responsibility to act as though Jesus is in the world wherever you go. Otherness “anything that is not you” This transition, from God as a Supreme Being to a part of life, can be understood well through one of the writings of Slavoj Žižek. Although he is not an advocate for Christianity such as Bonhoeffer or Tillich, his insight into death of God theology is nonetheless very useful. In The Parallax View, he writes, “God’s suffering implies that he is involved in history, affected by it, not just a transcendent Master pulling the strings from above: God’s suffering means that that human history is not just a theatre of the shadows but the place of real struggle, the struggle in which the Absolute itself is involved, and its fate is decided” (184). According to Žižek, the suffering of God is evidence that God is in the world and hence life is real because God is in the world. This is best understood within the context of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which Žižek has alluded to in his quotation. In the Allegory of the Cave, Plato explains of how a group of people who live in a cave have relied on shadows from puppets to convey truth about the world (209—210, 1985). They have seen only shadows, so to them, the shadows represent truth (209— 210, 1985). An instructor comes to set one of the men from the cave free, and through a painful struggle, that man learns to adjust his eyes to the sun and see the world as it is (210, 1985). In Plato’s allegory, the sun represents absolute truth, which is God (NOT my words, but I am unsure of who or what to cite. I cannot cite lectures.). Absolute truth is reflected through the shadows in the cave, which represent the reality we experience on Earth. The philosopher is the man who is set free from the cave. According to Žižek, God does not represent the sun. He argues that if God represents the sun, then God is not present in our world, the cave. Instead we only get shadows. This means that our “reality” is only a reflection of the real world, in which God lives. However, our world became real when God left God’s place as the sun1 to join our world. Specifically, when God allows God’s Self to suffer, does God become alive to us. What is the suffering that God gets to experience as an alive being? Nietzsche highlights pity as a particular way of suffering God experiences. However, the suffering God experiences “God…maintained himself in this process [of death], and the latter is only the death of death. God rises again to life, and thus things are reversed.” (Lectures 65). (Franke) The result is the creation of Absolute Spirit “I love him who chastens his god because he loves his god: for he must perish of the wrath of his god” (Nietzsche 16, 1978) However, pity is rooted not in love, but in hate. It is interesting to note that Žižek refers to God as a puppeteer rather than as the sun, which suggests that God is not absolute truth but rather a manipulator of absolute truth, a viewpoint consistent with the postmodern idea that there is no single ultimate religion. Nonetheless, the concept remains the same. Our world was not real because God was not actually here in the struggle; but now God has joined our world and is here in life’s struggles. 1 God is part of the life that must be negated (or is that life must regularly negate itself, and that includes God when God joins life?) Nietzsche had previously By this Nietzsche I feel like this must connect to God making straight paths crooked. And is this how we’re going to connect Tillich’s courage and Nietzsche’s life with the death of God! (Maybe) Nietzsche continues this idea, “Whatever I create and however much I love it—soon I must oppose it and my love; thus my will wills it. And you too, lover of knowledge, are only a path and footprint of my will; verily my will to power walks also on the heels of your will to truth” (115). Will to power: we created God (this is so weird) In order to understand God, we had to create God (Karl Barth). This also sounds a lot like Kant and concepts. So is Barth Kantian? But because we loved God, we had to kill God. Because love requires equality (this is a Platonic idea, right?), and the rest of Dr. J’s comment. And a love of knowledge hurts the will to truth through the will to power. This, I think, is the part about using reason to solve pity. Oo! This is so Platonic: we are made in the image of God! So cool! Nietzsche writes in Thus Spoke Zarathustra In order for God to come into our world, God must have pity on us. In order for us to be real, God must have pity on us But this doesn’t relate to us killing God out of our pity, out of us using reason (here we can use Nietzsche again, with regards to Tillich in saying that we must go beyond reason and live in faith and keep supporting the thesis) I so want to connect this to Nietzsche and succumbing to the wrath of God What if we need God’s wrath to succumb to it, just like we need absolute values through God (Dostoevsky) so that we can make our own values later? This is part of the paradox. God’s death is meaningful because God was first alive. The antithesis (and synthesis) comes because of the thesis. The death of religious values is meaningful because religious values were once so important. If there were no religious values to begin with, there would be no meaning The death of God is inspired from hate and resentment towards God, but it is a bringer of life and synthesis. It is necessary for our development. This creates a paradox for Nietzsche in which the will of eternal recurrence brings up ressentiment (or vice versa, I am really confused. Too much all-nighter) The paradox is that in order to embrace the freedom that a thesis promises you, you must go through an antithesis and synthesis. You have to kill the thesis in order for the thesis to have meaning. Of course, Tillich begs to differ. Bonhoeffer makes sense of Tillich because he puts God’s true existence as within the life of the Christian. If the Christian becomes alive through the death of “God” (God as defined by the Church or Western Orthodox society), then, God the thesis is actually reconfirmed through the death of “God.” This reconfirmation continues as long as the Christian continues to identify with suffering. God’s death gives us meaning because we love the life of God, but God must die in order that we may have life (so like short response paper) Reason develops to get rid of pity (but is more of a response to pity), more problems are solved, like evolution: struggle of natural selection, so no more human values. Humans destroy truth by promoting reason, we end up resenting God (now how to relate this to Zara?) The more human beings exercise their pity and using reason to solve the problems of the world, and as a result they come to the conclusion that God is dead. Does Tillich respond in saying that we need to return to the thesis and ignore the antithesis? Works Cited Altizer, Thomas J. J., ed. Toward a New Christianity: Readings in the Death of God Theology. United States of America: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1967. Print. Barth, Karl. Dogmatics in Outline. Thomas, G. T. trans. Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Letters & Papers from Prison. Bethge, Eberhard, ed. Fuller, Reginal, and Clark, Frank, trans. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997. Print. Franke, William. “The Deaths of God in Hegel and Neitzsche And The Crisis of Values in Secular Modernity And Post-Secular Postmodernity.” Religion & The Arts. 11.2 (2007): 214— 241. Academic Search Complete. Web 18 November 2015 Nietzsche, Friedrich. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for None and All. Kaufmann, Walter, trans. United States of America: Penguin Group, 1966. Print. Plato. The Republic. Sterling, Richard W. and Scott, William C., trans. New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton, 1985. Print. Tillich, Paul. The Courage to Be. Gomes, Peter J. trans. United States of America: Yale University Press, 1952. Print. Žižek, Slavoj. The Parallax View. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006. Print.