Unit 1 Short Stories

advertisement

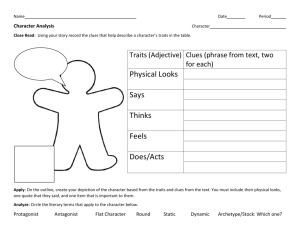

Page 1 of 22 GARY ALLAN HIGH SCHOOL ENG4C: Grade-12 College Unit 1 Short Stories To submit: 1. Answers for questions for four of the unit’s stories a. one of the stories must be “All the Years of Her Life” 2. Rubrics: “Short Story Questions” Remember: 1. Return your unit booklet when you submit your work. Page 2 of 22 Narrative Elements Setting: The time and location in which a story takes place is called the setting. a) place - geographical location. Where is the action of the story taking p lace? b) time - When is the story taking place? (historical period, time of day, year, etc) Atmosphere: the atmosphere is the feeling surrounding the setting. The light, darkness, weather, natural surroundings will affect the mood or feeling in a story. Plot: the plot is how the author arranges events to develop his basic idea: it is the sequence of events in a story or play. The plot is a planned, logical series of events having a beginning, middle, and end. There are five essential parts of plot: Introduction - The beginning of the story where the characters and the setting is revealed. The Trigger Incident-the event that starts the rising action. The main conflict of the story is introduced. Rising Action - This is where the events in the story become complicated. Climax - the protagonist makes a decision or takes an action which resolves the main conflict. Denouement - This is the final outcome or untangling of events in the story. Conflict: the conflict is essential to plot. Without conflict there is no plot. It is the opposition of forces which ties one incident to another and makes the plot move. There are four kinds of conflict: 1. Man vs. Man (physical) - The leading character struggles with his physical strength against other men, forces of nature, or animals. 2. Man vs. Circumstances (classical) - The leading character struggles against fate, or the circumstances of life facing him/her. 3. Man vs. Society (social) - The leading character struggles against ideas, practices, or customs of other people. 4. Man vs. Himself/Herself (psychological) - The leading character struggles with himself/herself; with his/her own soul, ideas of right or wrong, physical limitations, choices, etc. Character: There are two meanings for the word character: 1.The person in a work of fiction. 2.The characteristics or character traits of a person. Character traits refer to personality, not physical appearance. Persons in a work of fiction - Antagonist and Protagonist Short stories use few characters. One character is clearly central to the story with all major events having some importance to this character - he/she is the PROTAGONIST. The ANTAGONIST is the character who opposes the main character. The Characteristics of a Person In order for a story to seem real to the reader its characters must seem real. The author may reveal a character in several ways: 1. his/her physical appearance 2. what he/she says, thinks, feels and dreams 3. what he/she does or does not do 4. what others say about him/her and how others react to him/her Page 3 of 22 Point of view: Point of view, or p.o.v., is defined as the perspective from which the story is told. The person telling the story is the narrator. 1. First Person - The story is told by the protagonist (using pronouns I, me, we, etc). The reader sees the story through this person's eyes as he/she experiences it and only knows what he/she knows or feels. 2. Omniscient- The author can narrate the story using more than one point of view. He can move from character to character revealing the thinking of each. 3.Third person limited: the person telling the story is not part of the action. "He" or "she" presents the protagonist's perspective from "outside" the narrative. Theme: The theme in a piece of fiction is its controlling idea or its central insight. It is the author's underlying meaning or main idea that he is trying to convey. Some examples: Things are not always as they appear to be. Love cannot exist without trust Loss can teach important lessons Assignment Options A Man Who Had No Eyes by Mackinlay Kantor A beggar was coming down the avenue just as Mr. Parsons emerged from his hotel. He was a blind beggar, carrying the traditional battered can, and thumping his way before him with the cautious, half-furtive effort of the sightless. He was a shaggy, thick-necked fellow; his coat was greasy about the lapels and pockets, and his hand splayed over the cane’s crook with a futile sort of clinging. He wore a black pouch slung over his shoulder. Apparently he had something to sell. The air was rich with spring; sun was warm and yellowed on the asphalt. Mr. Parsons, standing there in front of his hotel and noting the clack-clack approach of the sightless man, felt a sudden and foolish sort of pity for all blind creatures. And, thought Mr. Parsons, he was very glad to be alive. A few years ago he had been little more than a skilled laborer; now he was successful, respected, admired… Insurance… And he had done it alone, unaided, struggling beneath handicaps… And he was still young. The blue air of spring, fresh from its memories of windy pools and lush shrubbery, could thrill him with eagerness. He took a step forward just as the tap-tapping blind man passed him by. Quickly the shabby fellow turned. "Listen guv’nor. Just a minute of your time." Mr. Parsons said, "It’s late. I have an appointment. Do you want me to give you something?" "I ain’t no beggar, guv’nor. You bet I ain’t. I got a handy little article here" he fumbled a small article into Mr. Parsons’ hand --- "that I sell. One buck. Best cigarette lighter made." Page 4 of 22 Mr. Parsons stood there, somewhat annoyed and embarrassed. He was a handsome figure with his immaculate grey suit and grey hat and malacca stick. Of course, the man with the cigarette lighter could not see him… "But I don’t smoke," he said. "Listen. I bet you know plenty people who smoke. Nice little present," wheedled the man. "And, mister, you wouldn’t mind helping a poor guy out?" He clung to Mr. Parsons’ sleeve. Mr. Parsons sighed and felt in his vest pocket. He brought out two half dollars and pressed them into the man’s hand. "Certainly I’ll help you out. As you say, I can give it to someone. Maybe the elevator boy would ---" He hesitated, not wishing to be boorish and inquisitive, even with a blind peddlar. "Have you lost your sight entirely?" The shabby man pocketed the two half dollars. "Fourteen years, guv’nor." Then he added with an insane sort of pride: "Westbury, sir, I was one of ‘em." "Westbury," repeated Mr. Parsons. "Ah yes. The chemical explosion . . . the papers haven’t mentioned it for years. But at the time it was supposed to be one of the greatest disasters in--- " "They’ve all forgot about it." The fellow shifted his feet wearily. "I tell you, guv’nor, a man who was in it don’t forget about it. Last thing I ever saw was C shop going up in one grand smudge, and that damn gas pouring in at all the busted windows." Mr. Parsons coughed. But the blind peddler was caught up with the train of his one dramatic reminiscence. And, also, he was thinking that there might be more half dollars in Mr. Parsons’ pocket. "Just think about it, guv’nor. There was a hundred and eight people killed, about two hundred injured, and over fifty of them lost their eyes. Blind as bats." He groped forward until his dirty hand rested against Mr. Parsons’ coat. "I tell you sir, there wasn’t nothing worse than that in the war. If I had lost my eyes in the war, okay. I would have been well took care of. But, I was just a worker, working for what was in it. And I got it. You’re damn right I got it, while the capitalists were making their dough! They was insured, don’t worry about that. They ---" "Insured," repeated his listener. "Yes, that’s what I sell. ---" "You want to know how I lost my eyes?" cried the man. "Well, here it is!" His words fell with the bitter and studied drama of a story often told and told for money. "I was there in C shop, last of all the folks rushin’ out. Out in the air there was a chance, even with buildings exploding right and left. A lot of guys made it safe out the door and got away. And just when I was about there, crawling along between those big vats, a guy behind me grabs my leg. He says, ‘Let me past, you ---! Maybe he was nuts. I dunno. I try to forgive him in my heart, guv’nor. But he was bigger than me. He hauls me back and climbs right over me! Tramples me into the dirt. And he gets out, and I lie there with all that poison gas pouring down on all sides of me, and flame and stuff . . ." He swallowed ---a studied sob---and stood dumbly expectant. He could imagine the next words: Tough luck, my man. Damned tough luck. Now I want to ---"That’s the story, guv’nor." The spring wind shrilled past them, damp and quivering. Not quite," said Mr. Parsons. The blind peddlar shivered crazily. "Not quite? What do you mean, you ---? " "The story is true," Mr. Parsons said, "except that it was the other way around." "Other way around?" He croaked unamiably. "Say, guv’nor---" "I was in C shop," said Mr. Parsons. "It was the other way around. You were the fellow who hauled back on me and climbed over me. You were bigger than I was, Markwardt." The blind man stood for a long time, swallowing hoarsely. He gulped: "Parsons. By heaven. By heaven! I thought you---" And then he screamed fiendishly: "Yes. Maybe so. Maybe so. But I’m blind! I’m blind, and you’ve been standing there letting me spout to you, and laughing at me every minute of it! I’m blind!" People in the street turned to stare at him. "You got away but I’m blind! Do you hear? I’m---" "Well," said Mr. Parsons, don’t make such a row about it, Markwardt…So am I." Page 5 of 22 Questions: 1. Referring to the text (by using direct quotations) describe each of the two characters in the story. Include at least two character traits for each. 2. Which man originally seems to deserve our sympathy? Why? How do our sympathetic feelings toward this character change? 3. How would you describe the atmosphere around the story? How does the setting contribute to this atmosphere? 4. Why does Markwardt tell the story about the chemical explosion? 5. A theme is the main underlying message, or moral, which the author tries to convey. What is the theme in this story, how is it developed and what line in the story best illustrates this theme? (requires, at least, one paragraph) All the Years of Her Life by Morley Callaghan The drug store was beginning to close for the night. Young Alfred Higgins who worked in the store was putting on his coat, getting ready to go home. On his way out, he passed Mr. Sam Carr, the little gray hair man who owned the store. Mr. Carr looked up at Alfred as he passed and said in a very soft voice, ''Just a moment, Alfred, one moment before you go.'' Mr. Carr spoke so quietly that he worried Alfred. ''What is it, Mr. Carr?'' ''Maybe you'd be good enough to take a few things out of your pockets and leave them here before you go.'' Said Mr. Carr. ''What things? What are you talking about?'' ''You've got a compact and a lipstick and at least two tubes of toothpaste in your pockets, Alfred.'' ''What do you mean?'' Alfred answered. ''Do you think I am crazy?'' His face got red. Mr. Carr kept looking at Alfred, coldly. Alfred did not know what to say and tried to keep his eyes from meeting the eyes of his boss. After a few moments, he put his hand into his pockets and took out the things he had stolen. ''Petty thieving, eh, Alfred?'' said Mr. Carr. ''And maybe you'd be good enough to tell me how long this has been going on.'' ''This is the first time I ever took anything.'' Mr. Carr was quick to answer, ''So now you think you tell me a lie? What kind of a fool do I look like, hah? I don't know what goes on in my own store, eh? I/ tell you, you have been doing this for a long time.'' Mr. Carr had a strange smile on his face. ''I don’t like to call the police,'' he said, ''but maybe I should call your father and let him know I'm going to have to put you in jail.'' ''My father is not home, he is a printer, he works nights.'' ''Who is at home?''Mr. Carr asked. ''My mother, I think.'' Mr. Carr started to go to the phone. Alfred's fears made him raise his voice. He wanted to show he was afraid of nobody. He acted this way every time he got into trouble. This had happened many times since he left school. At such times, he always spoke in a loud voice as he did tonight. Page 6 of 22 "Just a minute!" He said to Mr. Carr. "You don't have to get anybody else into this, you don't have to tell her." Alfred tried to sound big, but deep down he was like a child. He hoped that someone at home would come quickly to save him. But Mr. Carr was already talking to his mother, he told her to come to the store in a hurry. Alfred thought his mother would come rushing in, eyes burning with anger. Maybe she would be crying and would push him away when he tried to explain to her. She would made him feel so small. Yet he wanted her to come quickly before Mr. Carr called in a policeman. Alfred and Mr. Carr waited but said nothing, at last they heard someone at the closed door. Mr. Carr opened it and said, "Come in, Mrs. Higgins." His face was hard and serious. Alfred's mother came in with a friendly smile on her face and put out her hand to Mr. Carr and said politely, "I am Mrs. Higgins, Alfred's mother." Mr. Carr was surprised at the way she came in. She was very calm, quiet and friendly. "Is Alfred in trouble?" Mrs. Higgins asked. "He is, he has been taking things from the store, little things like toothpaste and lipsticks, things he can easily sell." Mrs. Higgins looked at her son and said sadly,"Is it so, Alfred?" "Yes". "Why have you been doing it?" she asked. "I've been spending money, I believe." "On what?" "Going around with the boys, I guess." said Alfred. Mrs. Higgins put out her hand and touched Mr. Carr's arm with great gentleness as if she knew just how he felt. She spoke as if she did not want to cause him any more trouble. She said, "If you will just listen to me before doing anything." Her voice was cool and she turned her head away as if she had said too much already. Then she looked again at Mr.Carr with a pleasant smile and asked, "What do you want to do, Mr.Carr?" "I was going to get a cop. That is what I should do, call a police." She answered, "Yes, I think so, it's not for me to say because he is my son. Yet I sometimes think a little good advice is the best thing for a boy at certain times in his life." Mrs. Higgins looks like a different woman to her son Alfred. There she was with a gentle smile saying, "I wonder if you don't think it would be better just to let him come home with me. He looks like a big fellow, doesn't he? Yet it takes some of them a long time to get any sense into their heads." Mr. Carr had expected Alfred's mother to come in nervously, shaking with fear, asking with wet eyes for a mercy for he son, but no, she was most calm and pleasant and was making Mr. Carr feel guilty. After a time, Mr. Carr was shaking his head in agreement with what she was saying. "Of course," he said, " I don't want to be cruel. I'll tell you what I'll do. Tell your son not to come back here again, and let it go at that, how is that?" And he warmly shook Mrs. Higgins's hand. "I will never forget your kindness. Sorry we had to meet this way," said Mr. Carr. "But I'm glad I got in touch with you, just wanted to do the right thing, that is all. "It's better to meet like this than never, isn't it?" She said. Suddenly they held hand as if they liked each other, as if they had known each other for a long time. "Good night, sir." "Good night, Mrs. Higgins. I'm truly sorry." Mother and son left. They walked along the street in silence. She took long steps and looked straight in front of her. After a time, Alfred said, "Thank Dod it turned out like that, never again!" "Be quiet, don't speak to me, you have shamed me enough, have the decency to be quiet." Page 7 of 22 They reached home at last. Mrs. Higgins took off her coat and without even looking at him, she said to Alfred, "You are a bad luck. God forgive you. It is one thing after another, always has been. Why do you stand there so stupidly? go to bed." As she went into the kitchen, she said, "Not a word about tonight to your father." In his bedroom, Alfred heard his mother in the kitchen. There was no shame in him, just pride in his mother's strength. "She was smooth!" he said to himself. He felt he must tell her how great she was. As he got to the kitchen, he saw his mother drinking a cup of tea. He was shocked by what he saw. His mother's face, as she said, was a frightened, broken face. It was not the same cool, bright face he saw earlier in the drug store. As Mrs. Higgins lifted the tea cup, her hand shook. And some of the tea splashed on the table. Her lips moved nervously. She looked very old. He watched his mother without making a sound. The picture of his mother made him want to cry. He felt his youth coming to an end. He saw all the troubles he brought his mother in her shaking hand and the deep lines of worry in her grey face. It seemed to him that this was the first time he had ever really seen his mother. The author comments on his own story: This story was written with astonishing ease – almost as if I were remembering something. A writer is very lucky when someone tells him a little story that is half complete. What has been given to him in this way seems to set his imagination off, and, almost at once he finds himself completing the story in his mind….The story, “All the Years of Her Life” came out of a scene that had been very real to me. I saw a middle-aged woman who had just saved her son from some trouble with the law. Her simple, effortless dignity, which was all she had to protect her son, had been overwhelming. It had actually embarrassed the man who had proposed to prosecute her son. Of course, the mother afterwards was really rattled. The son at first didn’t understand her strange magic. His wonder was in her face. I knew about this story for a long time before I wrote it. Then one day I seemed to know what went on in the boy’s heart as he watched his mother at home, having a cup of tea after the battle, and he tried to understand the years of her life – his own mother, his own life with her. I started to write this story late one afternoon. I had finished by dinnertime. I knew that the whole success or failure of the story had to come in the last paragraph. So, I kept the story around for about a week, repeating it aloud, and I knew I didn’t want to change any of it. There was no plotting or planning of [this] story. It had to come out like a poem; there had to be a total poignant impact, and first, of course, this impact had to be on me. Questions: 1. Like “Two Fishermen” and “The Snob”, this story by Morley Callaghan revolves around a dilemma or conflict that requires a choice or action on the part of one of the main characters. In this instance, the conflict’s focus is largely within the context of a family. Discuss the dilemma facing each of Sam Carr, Alfred and Mrs. Higgins. Do you agree with the way each of these characters resolves his/her respective dilemma? In a short paragraph for each character explain why or why not. 2. Callaghan is noted for writing about ordinary, everyday people in ordinary, everyday settings. To some extent, we can all relate to the problems faced by his characters. In your opinion, is Callaghan’s storytelling effective? With references to specific moments, sequences or descriptions from the story, justify your response. Page 8 of 22 3. At the end of the story, Alfred learns a lesson about life and his place in it. Using at least one quotation from the piece, discuss what you believe that lesson is. Before you conclude your answer to this question, look back to the author’s own comments about “All the Years of Her Life”, especially concerning the last paragraph. From your point of view was he correct in not changing any of the last paragraph? Does it achieve that “poignant impact” that he was aiming for? 4. Research the issue of teenage shoplifting on the Internet. Try to find two articles which give you some facts, examples, and perhaps even some of the motivations for this behaviour. Try to focus on the issue as it relates to young people, like Alfred, in the story, but if you find valuable or interesting material that deals with the issue on a more general basis. Feel free to select it. Read through these two articles and submit them, along with the following: a brief summary paragraph for each article one quotation from each article that embodies or summarizes each article’s main idea—feel free to use more than one quotation if you feel that it is necessary 5. Keep the research that you’ve done on these articles to give you ammunition for the next task: You’ve just found out that your child has been caught shoplifting. Compose the lecture that you’re going to give him/her when you pick-up the child at the police station, or at the place of business where he/she has been caught. You decide the tone. You decide how serious you’re going to be and whether or not you’re going to use personal anecdotes or statistics, or both as part of this speech. Make certain to identify the age of the child involved; that would obviously influence what you say and how you say it. Your lecture should be approximately ¾ to 1 page in length. The Snob Morley Callaghan It was at the book counter in the department store that John Harcourt, the student, caught a glimpse of his father. At first he could not be sure in the crowd that pushed along the aisle, but there was something about the color of the back of the elderly man’s neck, something about the faded felt hat, that he knew very well. Harcourt was standing with the girl he loved, buying a book for her. All afternoon he had been talking to her, eagerly, but with an anxious diffidence, as if there still remained in him an innocent wonder that she should be delighted to be with him. From underneath her wide-brimmed straw hat, her face, so fair and beautifully strong with its expression of cool independence, kept turning up to him and sometimes smiled at what he said. That was the way they always talked, never daring to show much full, strong feeling. Harcourt had just bought the book, and had reached into his pocket for the money with a free, ready gesture to make it appear that he was accustomed to buying books for young ladies, when the white-haired man in the faded felt hat, at the other end of the counter, turned half-toward him, and Harcourt knew he was standing only a few feet away from his father. The young man’s easy words trailed away and his voice became little more than a whisper, as if he were afraid that everyone in the store might recognize it. There was rising in him a dreadful uneasiness; something very precious that he wanted to hold seemed close to destruction. His father, standing at the end of the bargain counter, was planted squarely on his two feet, turning a book over thoughtfully in his hands. Then he took out his glasses from an old, worn leather case and adjusted them on the end of his nose, looking down over them at the book. His coat was thrown open, two buttons on his vest were undone, his hair was too long, and in his rather shabby clothes he looked very much like a workingman, a carpenter perhaps. Such a resentment Page 9 of 22 rose in young Harcourt that he wanted to cry out bitterly, “Why does he dress as if he never owned a decent suit in his life? He doesn’t care what the whole world thinks of him. He never did. I’ve told him a hundred times he ought to wear his good clothes when he goes out. Mother’s told him the same thing. He just laughs. And now Grace may see him. Grace will meet him.” So young Harcourt stood still, with his head down, feeling that something very painful was impending. Once he looked anxiously at Grace, who had turned to the bargain counter. Among those people drifting aimlessly by with hot red faces, getting in each other’s way, using their elbows but keeping their faces detached and wooden, she looked tall and splendidly alone. She was so sure of herself, her relation to the people in the aisles, the clerks behind the counters, the books on the shelves, and everything around her. Still keeping his head down and moving close, he whispered uneasily, “Let’s go and have tea somewhere, Grace.” “In a minute, dear,” she said. “Let’s go now.” “In just a minute, dear,” she repeated absently. “There’s not a breath of air in here. Let’s go now.” “What makes you so impatient?” “There’s nothing but old books on that counter.” “There may be something here I’ve wanted all my life,” she said, smiling at him brightly and not noticing the uneasiness in his face. So Harcourt had to move slowly behind her, getting closer to his father all the time. He could feel the space that separated them narrowing. Once he looked up with an unclear, sidelong glance. But his father, red-faced and happy, was still reading the book, only now there was a meditative expression on his face, as if something in the book had stirred him and he intended to stay there reading for some time. Old Harcourt had lots of time to amuse himself, because he was on a pension after working hard all his life. He had sent John to the university and he was eager to have him do well. Every night when John came home, whether it was early or late, he used to go into his father and mother’s bedroom and turn on the light and talk to them about the interesting things that had happened to him during the day. They listened and shared this new world with him. They both sat up in their night clothes and, while his mother asked all the questions, his father listened attentively with his head cocked on one side and a smile or a frown on his face. The memory of all this was in John now, and there was also a desperate longing and a pain within him growing harder to bear as he glanced fearfully at his father, but he thought stubbornly, “I can’t introduce him. It’ll be easier for everybody if he doesn’t see us. I’m not ashamed. But it will be easier. It’ll be more sensible. It’ll only embarrass him to see Grace.” By this time he knew he was ashamed, but he felt that his shame was reasonable, for Grace’s father had the smooth, confident manner of a man who had lived all his life among people who were rich and sure of themselves. Often when he had been in Grace’s home talking politely to her mother, John had kept on thinking of the plainness of his own home and of his parents’ laughing, good-natured untidiness, and he resolved desperately that he must make Grace’s people admire him. He looked up carefully, for they were about eight feet away from his father, but at that moment his father, too, looked up and John’s glance shifted swiftly far over the aisle, over the counters, seeing nothing. As his father’s blue, calm eyes stared steadily over the glasses, there was an instant when their glances might have met. Neither one could have been certain, yet John, as he turned away and began to talk hurriedly to Grace, knew surely that his father had seen him. He knew it by the steady calmness in his father’s blue eyes. John’s shame grew, and then embarrassment sickened him as he waited and did nothing. His father turned away, going down the aisle, walking erectly in his shabby clothes, his shoulders very straight, never once looking back. His father would walk slowly down the street, he knew, with that thoughtful expression deepening and becoming grave. Page 10 of 22 Young Harcourt stood beside Grace, brushing against her soft shoulder, and made faintly aware again of the delicate scent she used. There, so close beside him, she was holding within her everything he wanted to reach out for, only now he felt a sharp hostility that made him sullen and silent. “You were right, John,” she was drawling in her soft voice. “It does get unbearable in here on a hot day. Do let’s go now. Have you ever noticed that department stores after a time can make you really hate people?” But she smiled when she spoke, so he might see that she really hated no one. “You don’t like people, do you?” he said sharply. “People? What people? What do you mean?” “I mean,” he went on irritably, “you don’t like the kind of people you bump into here, for example.” “Not especially. Who does? What are you talking about?” “Anybody could see you don’t,” he said, full of a savage eagerness to hurt her. “I say you don’t like simple, honest people, the kind of people you meet all over the city.” He blurted the words out as if he wanted to shake her, but he was longing to say, “You wouldn’t like my family. Why couldn’t I take you home to have dinner with them? You’d turn up your nose at them, because they’ve no pretensions. As soon as my father saw you, he knew you wouldn’t want to meet him. I could tell by the way he turned.” His father was on his way home now, he knew, and that evening at dinner they would meet. His mother and sister would talk rapidly, but his father would say nothing to him, or to anyone. There would only be Harcourt’s memory of the level look in the blue eyes, and the knowledge of his father’s pain as he walked away. Grace watched John’s gloomy face as they walked through the store, and she knew he was nursing some private rage, and so her own anger and exasperation kept growing, and she said crisply, “You’re entitled to your moods on a hot afternoon, I suppose, but if I feel I don’t like it here, then I don’t like it. You wanted to go yourself. Who likes to spend very much time in a department store on a hot afternoon? I begin to hate every stupid person that bangs into me, everybody near me. What does that make me?” “It makes you a snob.” “So I’m a snob now?” she asked angrily. “Certainly you’re a snob,” he said. They were at the door and going out to the street. As they walked in the sunlight, in the crowd moving slowly down the street, he was searching for words to describe the secret thoughts he had always had about her. “I’ve always known how you’d feel about people I like who didn’t fit into your private world,” he said. “You’re a very stupid person,” she said. Her face was flushed now, and it was hard for her to express her indignation, so she stared straight ahead as she walked along. They had never talked in this way, and now they were both quickly eager to hurt each other. With a flow of words, she started to argue with him, then she checked herself and said calmly, “Listen, John, I imagine you’re tired of my company. There’s no sense in having tea together. I think I’d better leave you right here.” “That’s fine,” he said. “Good afternoon.” “Good-by.” “Good-by.” She started to go, she had gone two paces, but he reached out desperately and held her arm, and he was frightened, and pleading, “Please don’t go, Grace.” All the anger and irritation had left him; there was just a desperate anxiety in his voice as he pleaded, “Please forgive me. I’ve no right to talk to you like that. I don’t know why I’m so rude or what’s the matter. I’m ridiculous. I’m very, very ridiculous. Please, you must forgive me. Don’t leave me.” He had never talked to her so brokenly, and his sincerity, the depth of his feeling, began to stir her. While she listened, feeling all the yearning in him, they seemed to have been brought closer together, by opposing each other, than ever before, and she began to feel almost shy. “I don’t know what’s the matter. I suppose we’re both irritable. It must be the weather,” she said. “But I’m not angry, John.” Page 11 of 22 He nodded his head miserably. He longed to tell her that he was sure she would have been charming to his father, but he had never felt so wretched in his life. He held her arm tight, as if he must hold it or what he wanted most in the world would slip away from him, yet he kept thinking, as he would ever think, of his father walking away quietly with his head never turning. Questions: 1. Discuss why you think John makes the decision to ignore his father. Make sure to include quotations that clearly explain John’s justification for this form of discrimination. 2. Describe the possible irony of the story’s title, by suggesting who John assumes might be the snob and who really is. 3. Callaghan’s stories usually contain a subtle but significant comment about human nature. What do you feel is the ‘lesson’ in this story, and how does it parallel the message that seems to be there in “Two Fishermen”? 4. Application journal: Consider the situation that occurs in “The Snob”. Try to think about a similar situation in your own life, when you’ve either been the snob or the victim of someone else’s snobbery. In a few well- composed paragraphs, write a personal response describing how it felt to be in either of those positions. Two Fishermen By Morley Callaghan The only reporter on the town paper, the Examiner, was Michael Foster, a tall, long-legged, eager young fellow; who wanted to go to the city some day and work on an important newspaper. The morning he went into Bagley's Hotel, he wasn't at all sure of himself. He went over to the desk and whispered to the proprietor, Ted Bagley, "Did he come here, Mr. Bagley?” Bagley said slowly, "Two men came here from this morning's train. They're registered.” He put his spatulate forefinger on the open book and said, "Two men. One of them's a drummer. This one here, T. Woodley. I know because he was through this way last year and just a minute ago he walked across the road to Molson's hardware store. The other one—here's his name, K Smith. H "Who's K Smith?" Michael asked. “I don't know. A mild, harmless. looking little guy.” “Did he look like the hangman, Mr. Bagley?" "I couldn't say that, seeing as I never saw one. He was awfully polite and asked where he could get a boat so he could go fishing on the lake this evening, so I said likely down at Smollet's place by the power-house." "Well, thanks. I guess if he was the hangman, he'd go over to the jail first," Michael said. He went along the street, past the Baptist church to the old jail with the high brick fence around it. Two tall maple trees, with branches dropping low over the sidewalk, shaded one of the walls from the morning sunlight. Last night, behind those walls, three carpenters, working by lamplight, had nailed the timbers for the scaffold. In the morning, young Thomas Delaney, who had grown up in the town, was being hanged: he had killed old Mathew Rhinehart whom he had caught molesting his wife when she had been berry picking in the hills behind the town. There had been a struggle and Thomas Delaney had taken a bad beating before he had killed Rhinehart Last night a crowd had gathered on the sidewalk by the lamp-post, and while moths and smaller insects swarmed around the high blue carbon light, the Page 12 of 22 crowd had thrown sticks and bottles and small stones at the out-of-town workmen in the jail yard. Billy Hilton, the town constable, had stood under the light with his head down, pretending riot to notice anything. Thomas Delaney was only three years older than Michael Foster. Michael went straight to the jail office where Henry Steadman, the sheriff, a squat, heavy man, was sitting on the desk idly wetting his long moustaches with his tongue. “Hello, Michael, what do you want?” he asked. “Hello, Mr. Steadman, the Examiner would like to know if the hangman arrived yet." “Why ask me?" “I thought he’d come here to test the gallows. Won't he?" “My, you're a smart young fellow, Michael, thinking of that." Is he here now, Mr. Steadman?" “Don’t ask me. I'm saying nothing. Say, Michael, do you think there’s. 'going to be trouble? You ought to know. Does anybody seem sore at me? I can’t do nothing. You can see that." I don’t think anybody blames you, Mr. Steadman. Look here, can't I see the hangman? Is his name K. Smith?" “What does it matter to you, Michael? Be a sport, go on away and don’t bother us anymore." “All right, Mr. Steadman," Michael said very competently, just leave to me." Early that evening, when the sun was setting, Michael Foster walked south of town on the dusty road leading to the power-house and Smollet’s fishing pier. He knew that if Mr. K. Smith wanted to get a boat he would go down to the pier. Fine powdered road dust whitened Michael’s shoes. Ahead of him he saw the power-plant, square and the smooth lake water. Behind him the sun was hanging over the hills beyond the town and shining brilliantly on square patches of farm land. The air around the powerhouse smelt of steam. Out on the jutting, tumbledown pier of rock and logs, Michael saw a little fellow without a hat, sitting down with his knees hunched up to his chin, a very small man with little grey baby curls on the back of his neck, who stared steadily far out over the water. In his hand he was holding stick with a heavy fishing-line twined around it and a gleaming copper spoon bait, the hooks brightened with bits of feathers such as they used in the neighbourhood when trolling for lake trout. Apprehensively Michael walked out over the rocks toward the stranger and called, “Were you thinking of going fishing, mister?" Standing up, the man smiled. He had a large head, tapering down to a small chin, a birdlike neck: and a very wistful smile. Puckering his mouth up, he said shyly to Michael, “Did you intend to go fishing?” "That's what I came down here for. I was going to get a boat back at the boat-house there. How would you like if we went together?" “I’d like it first rate, "the shy little man said eagerly."We could take turns rowing. Does that appeal to you?" "Fine. Fine. You wait here, and I'll go back to Smollet's place and ask for a row-boat and I'll row around here and get you." “Thanks. Thanks very much," the mild little man said as he began to untie his line. He seemed very enthusiastic. When Michael brought the boat around to the end of the old pier and invited the stranger to make himself comfortable so he could handle the line, the stranger protested comically that he ought to be allowed to row. Pulling strong at the oars, Michael was soon out in the deep water and the little man was letting his line out slowly. In one furtive glance, he had noticed that the man's hair, grey at the temples, was inclined to curl to his ears. The line was out full length. It was twisted around the little man's forefinger, which he let drag in the water. And then Michael. looked full at him and smiled because he thought he seemed so meek and quizzical. "He's a nice little guy," Michael assured himself and he said, "I work on the town paper, the Examiner." Page 13 of 22 “Is it a good paper? Do you like the work?" "Yes, but it's nothing like a first-class city paper and I don't expect to be working on it long. I want to get a reporter's job on a city paper. My name's Michael Poster." "Mine's Smith. Just call me Smitty." "I was wondering if you'd been over to the jail yet." Up to this time the little man had been smiling with the charming ease of a small boy who finds himself free, but now he became furtive and disappointed. Hesitating, he said, "Yes, I was over there first thing this morning." "Oh, I just knew you'd go there," Michael said. They were a bit afraid of each other. By this time they were far out on the water which had a mill-pond smoothness. The town seemed to get smaller, with white houses in rows and streets forming geometric patterns, just as the blue hills behind the town seemed to get larger at sundown. Finally Michael said, "Do you know this Thomas Delaney that's dying in the morning?" He knew his voice was slow and resentful. "No, I don't know anything about him. I never read about them. Aren't there any fish at all in this old lake? I'd like to catch some fish," he said rapidly. "I told my wife 1'd bring her home some fish." Glancing at Michael, he was appealing without speaking that they should do nothing to spoil an evening's fishing. The little man began to talk eagerly about fishing as he pulled out a small flask from his hip pocket. “Scotch," he said, chuckling with delight. “Here, take a swig.” Michael drank from the flask and passed it back. Tilting his head back and saying, "Here's to you, Michael," the little man took a long pull at the flask. "The only time I take a drink,”' he said still chuckling, "is when I go on a fishing trip by myself. I usually go by myself,” he added apologetically, as if he wanted the young fellow to see how much he appreciated his company. They had gone far out on the water but they had caught nothing. It began to get dark. "No fish tonight, I guess, Smitty," Michael said. "It's a crying shame,” Smitty said. "I looked forward to coming up here when I found out the place was on the lake. I wanted to get some fishing in. I promised my wife I'd bring her back some fish. She'd often like to go fishing with me, but of course, she can't because she can't travel around from place to place like I do. Whenever I get a call to go some place, I always look at the map to see if it's by a lake or on a river, then I take my lines and hooks along." "If you took another job, you and your wife could probably go fishing together," Michael suggested. "I don't know about that. We sometimes go fishing together anyway." He looked away, waiting for Michael to be repelled and insist that he ought to give up the job. And he wasn't ashamed as he looked down at the water, but he knew that Michael thought he ought to be ashamed. "Somebody's got to do my job. There's got to be a hangman,” he said. “I just meant that if it was such disagreeable work, Smitty." The little man did not answer for a long time. Michael rowed steadily with sweeping, tireless strokes. Huddled at the end of the boat, Smitty suddenly looked up with a kind of melancholy hopelessness and said mildly, "The job hasn't been so disagreeable.” “Good God, man, you don't mean you like it?" "Oh, no," he said, to be obliging, as if he knew what Michael expected him to say. "I mean you get used to it, that's all." But he looked down again at the water, knowing he ought to be ashamed of himself. "Have you got any children?" “I sure have. Five. The oldest boy is fourteen. It’s funny, but they're all a lot bigger and taller than I am. Isn't that funny?" They started a conversation about fishing rivers that ran into ·the lake farther north. They felt friendly again. The little man, who had an extraordinary gift for storytelling, made many quaint faces, Page 14 of 22 puckered up his lips, screwed up his eyes and moved around restlessly as if he wanted to get up in the boat and stride around for the sake of more expression. Again he brought out the whiskey flask and Michael stopped rowing. Grinning, they toasted each other and said together, "Happy days.” The boat remained motionless on the placid water. Far out, the sun's last rays gleamed on the waterline. And then it got dark and they could only see the town lights. It was time to turn around and pull for the shore. The little man tried to take the oars from Michael, who shook his head resolutely: and insisted that he would prefer to have his friend catch a fish on the way back to the shore. “It’s too late now and we may have scared all the fish away," Smitty laughed happily. “But we're having a grand time, aren't we?" When they reached the old pier by the power-house, it was full night and they hadn't caught a single fish. As the boat bumped against the rocks Michael said, "You can get out here. 111 take the boat around to Smollet's.” “Won't you be coming my way?" “Not just now. I’ll probably talk with Smollet a while." The little man got out of the boat and stood on the pier looking down at Michael. “I was thinking dawn would be the best time to catch some fish," he said. “At about five o'clock. I'll have an hour and a half to spare anyway. How would you like that?” He was speaking with so much eagerness that Michael found himself saying, "I could try. But if I'm not here at dawn, you go on without me." “All right. I'll walk back to the hotel now.” "Good night, Smitty.” “Good night, Michael. We had a fine, neighbourly time, didn't we?" As Michael rowed the boat around to the boat-house, he hoped that Smitty wouldn't realize he didn't want to be seen walking back to town with him. And later, when he was going slowly along the dusty road in the dark and hearing the crickets chirping in the ditches, he couldn't figure out why he felt so ashamed of himself. At seven o'clock next morning Thomas Delaney was hanged in the town jail yard. There was hardly a breeze on that leaden grey morning and there were no small white-caps out over the lake. It would have been a fine morning for fishing. Michael went down to the jail, for he thought it his duty as a newspaperman to have all the facts, but he was afraid he might get sick. He hardly spoke to all the men and women who were crowded under the maple trees by the jail wall. Everybody he knew was staring at the wall and muttering angrily. Two of Thomas Delaney's brothers, big, strapping fellows with bearded faces, were there on the sidewalk. Three automobiles were at the front of the jail. Michael, the town newspaperman, was admitted into the courtyard by old Willie Mathews, one of the guards, who said that two newspapermen from the city were at the gallows on the other side of the building. “I guess you can go around there, too, if you want to," Mathews said, as he sat down slowly on the step. White-faced, and afraid, Michael sat down on the step with Mathews and they waited and said nothing. At last the old fellow said, “Those people outside there are pretty sore, ain't they?" They're pretty sullen, all right. I saw two of Delaney's brothers there." "I wish they'd go,” Mathews said. “I don't want to see anything. I didn't even look at Delaney. I don't want to hear anything. I'm sick." He put his head back against the wall and closed his eyes. "The old fellow and Michael sat close together till a small procession came around the comer from the other side of the yard. First came Mr. Steadman- the sheriff, with his head down as though he were crying, then Dr. Parker, the physician, then two hard-looking young newspapermen from the city, walking with their hats on the backs of their heads, and behind them came the little hangman, erect, stepping out with military precision and carrying himself with a strange cocky dignity. He was dressed in a long black cut-away coat with grey striped trousers, a gates-ajar collar and a narrow red tie, as if he alone felt the formal importance of the occasion. He walked with brusque precision till he saw Michael, who was standing up, staring at him with his mouth open. Page 15 of 22 The little hangman grinned and as soon as the procession reached the doorstep, he shook hands with Michael. They were all looking at Michael. As though his work were over now, the hangman said eagerly to Michael, "I thought I'd see you here. You didn't get down to the pier at dawn?” "No. I couldn't make it.” “That was tough, Michael. I looked for you,” he said. "But never mind. I've got something for you." As they all went into the jail, Dr. Parker glanced angrily at Michael, then turned his back to him. In the office, where the doctor prepared to sign a certificate, Smitty was bending down over his fishing-basket which was in the comer. Then he pulled out two good-sized salmon-bellied trout, folded in a newspaper, and said, "I was saving these for you, Michael. I four in an hour’s straight fishing.” Then he said, “I'll talk about that later, if you'll wait. We'll be busy here, and I've got to change my clothes.” Michael went out to the street with Dr. Parker and the two city newspapermen. Under his arm he was carrying the fish, folded in the newspaper. Outside, at the jail door, Michael thought that the doctor and the two newspapermen were standing a little apart from him. Then the small crowd, with their clothes all dust-soiled from the road, surged forward, and the doctor said to them, "You might as well go home, boys. It's all over." "Where's old Steadman?" somebody demanded. “We’ll wait for the hangman," somebody else shouted. The doctor walked away by himself. For a while Michael stood beside the two city newspapermen, and tried to look as nonchalant as they were looking, but he lost confidence in them when he smelled whiskey. They only talked to each other. Then they mingled with the crowd, and Michael stood alone. At last he could stand there no longer looking at all those people he knew so well, so he, too, moved out and joined the crowd. When the sheriff came out with the hangman and two of the guards, they got half-way down to one of the automobiles before someone threw an old boot. Steadman ducked into one of the cars, as the boot hit him on the shoulder, and the two guards followed him. The hangman, dismayed, stood alone on the sidewalk. Those in the car must have thought at first that the hangman was with them for the car suddenly shot forward, leaving him alone on the sidewalk. The crowd threw small rocks and sticks, hooting at him as the automobile backed up slowly towards him. One small stone hit him on the head. Blood trickled from the side of his head as he looked around helplessly at all the angry people. He had the same expression on his face, Michael thought, as he had had last night when he had seemed ashamed and had looked down steadily at the water. Only now, he looked around wildly, looking for someone to help him as the crowd kept pelting him. Farther and farther Michael backed into the crowd and all the time he felt dreadfully ashamed as though he were betraying Smitty, who last night had had such a good neighbourly time with him. “It’s different now, it's different,” he kept thinking, as he held the fish in the newspaper tight under his arm. Smitty started to run toward the automobile, but James Mortimer, a big fisherman, shot out his foot and tripped him and sent him sprawling on his face. Mortimer, the big fisherman, looking for something to throw, said to Michael, “Sock him, sock him.” Michael shook his head and felt sick. "What's the matter with you, Michael?” "Nothing. I got nothing against him." The big fisherman started pounding his fists up and down in the air. “He just doesn't mean anything to me at all," Michael said quickly. The fisherman, bending down, kicked a small rock loose from the road bed and heaved it at the hangman. Then he said, “What are you holding there, Michael, what's under your arm? Fish. Pitch them at him. Here, give them to me." Still in a fury, he snatched the fish, and threw them one at a time at the little man just as he was getting up from the road. The fish fell in the thick dust in front of him, sending up a little cloud. Smitty seemed to stare at the fish with his mouth hanging open, then he didn't even look at the crowd. That expression on Smitty's face as he saw the fish on the road made Michael hot with shame and he tried to get out of the crowd. Smitty had his hands over his head, to shield his face as the crowd pelted him, yelling "Sock the Page 16 of 22 little rat. Throw the runt in the lake." The sheriff pulled him into the automobile. The car shot forward in a cloud of dust. Questions: 1. Briefly explain the situation, involving Thomas Delaney, that has brought Smitty to this town. 2. Callaghan is thought to be a master of the short story form because he is so good at capturing his characters with quick but precise strokes. Quote THREE detailed descriptions of Smitty, and suggest why each one is so effective in setting-up the apparent contrast between him and his profession. 3. Describe what you think Michael’s motives are, first in befriending Smitty, and then, ultimately, in betraying him. 4. What ‘message(s)’ do you take away from this piece? Explain your interpretation with specific references to the story. 5. Respond to the statement, “No one in the story is really guilty.” Discuss the reasoning that led you to this conclusion by mentioning at least THREE characters, or groups of characters, in the story. 6. With as much honesty as you can, suggest how you believe you would have reacted if you had been faced with the same dilemma that Michael is at the story’s conclusion. Your response should be approximately ¾ of a page to a full page. The Possibility of Evil by Shirley Jackson Miss Strangeworth is a familiar fixture in a small town where everyone knows everyone else. Little do the townsfolk suspect, though, that the dignified old woman leads another, secret life... Miss Adela Strangeworth came daintily along Main Street on her way to the grocery. The sun was shining, the air was fresh and clear after the night's heavy rain, and everything in Miss Strangeworth's little town looked washed and bright. Miss Strangeworth took deep breaths and thought that there was nothing in the world like a fragrant summer day. She knew everyone in town, of course; she was fond of telling strangers—tourists who sometimes passed through the town and stopped to admire Miss Strangeworth's roses—that she had never spent more than a day outside this town in all her long life. She was seventy-one, Miss Strangeworth told the tourists, with a pretty little dimple showing by her lip, and she sometimes found herself thinking that the town belonged to her. "My grandfather built the first house on Pleasant Street," she would say, opening her blue eyes wide with the wonder of it. "This house, right here."My family has lived here for better than a hundred years. My grandmother planted these roses, and my mother tended them, just as I do. I've watched my town grow; I can remember when Mr. Lewis, Senior, opened the grocery store, and the year the river flooded out the shanties on the low road, and the excitement when some young folks wanted to move the park over to the space in front of where the new post office is today. They wanted to put up a statue of Ethan Allen"—Miss Strangeworth would frown a little and sound stern—"but it should have been a statue of my grandfather. There wouldn't have been a town here at all if it hadn't been for my grandfather and the lumber mill." Page 17 of 22 Miss Strangeworth never gave away any of her roses, although the tourists often asked her. The roses belonged on Pleasant Street, and it bothered Miss Strangeworth to think of people wanting to carry them away, to take them into strange towns and down strange streets. When the new minister came, and the ladies were gathering flowers to decorate the church, Miss Strangeworth sent over a great basket of gladioli; when she picked the roses at all, she set them in bowls and vases around the inside of the house her grandfather had built. Walking down Main Street on a summer morning, Miss Strangeworth had to stop every minute or so to say good morning to someone or to ask after someone's health. When she came into the grocery, half a dozen people turned away from the shelves and the counters to wave at her or call out good morning. "And good morning to you, too, Mr. Lewis," Miss Strangeworth said at last. The Lewis family had been in the town almost as long as the Strangeworths; but the day young Lewis left high school and went to work in the grocery, Miss Strangeworth had stopped calling him Tommy and started calling him Mr. Lewis, and he had stopped calling her Addie and started calling her Miss Strangeworth. They had been in high school together, and had gone to picnics together, and to high-school dances and basketball games; but now Mr. Lewis was behind the counter in the grocery, and Miss Strangeworth was living alone in the Strangeworth house on Pleasant Street. "Good morning," Mr. Lewis said, and added politely, "Lovely day." End of Section One "It is a very nice day," Miss Strangeworth said, as though she had only just decided that it would do after all. "I would like a chop, please, Mr. Lewis, a small, lean veal chop. Are those strawberries from Arthur Parker's garden? They're early this year." "He brought them in this morning," Mr. Lewis said. "I shall have a box," Miss Strangeworth said. Mr. Lewis looked worried, she thought, and for a minute she hesitated, but then she decided that he surely could not be worried over the strawberries. He looked very tired indeed. He was usually so chipper, Miss Strangeworth thought, and almost commented, but it was far too personal a subject to be introduced to Mr. Lewis, the grocer, so she only said, "and a can of cat food and, I think, a tomato." Silently, Mr. Lewis assembled her order on the counter, and waited. Miss Strangeworth looked at him curiously and then said, "It's Tuesday, Mr. Lewis. You forgot to remind me." "Did I? Sorry." "Imagine your forgetting that I always buy my tea on Tuesday," Miss Strangeworth said gently. "A quarter pound of tea, please, Mr. Lewis." "Is that all, Miss Strangeworth?" "Yes, thank you, Mr. Lewis. Such a lovely day, isn't it?" "Lovely," Mr. Lewis said. Miss Strangeworth moved slightly to make room for Mrs. Harper at the counter. "Morning, Adela," Mrs. Harper said, and Miss Strangeworth said, "Good morning, Martha." "Lovely day," Mrs. Harper said, and Miss Strangeworth said, "Yes, lovely," and Mr. Lewis, under Mrs. Harper's glance, nodded. "Ran out of sugar for my cake frosting," Mrs. Harper explained. Her hand shook slightly as she opened her pocketbook. Miss Strangeworth wondered, glancing at her quickly, if she had been taking proper care of herself. Martha Harper was not as young as she used to be, Miss Strangeworth thought. She probably could use a good strong tonic. "Martha," she said, "you don't look well." "I'm perfectly all right," Mrs. Harper said shortly. She handed her money to Mr. Lewis, took her change and her sugar, and went out without speaking again. Looking after her, Miss Strangeworth shook her head slightly. Martha definitely did not look well. Page 18 of 22 Carrying her little bag of groceries, Miss Strangeworth came out of the store into the bright sunlight and stopped to smile down on the Crane baby. Don and Helen Crane were really the two most infatuated young parents she had ever known, she thought indulgently, looking at the delicately embroidered baby cap and the lace edged carriage cover. "That little girl is going to grow up expecting luxury all her life," she said to Helen Crane. Helen laughed. "That's the way we want her to feel," she said. "Like a princess." End of Section Two "A princess can see a lot of trouble sometimes," Miss Strangeworth said dryly. "How old is Her Highness now?" "Six months next Tuesday," Helen Crane said, looking down with rapt wonder at her child. "I've been worrying, though, about her. Don't you think she ought to move around more? Try to sit up, for instance?" "For plain and fancy worrying," Miss Strangeworth said, amused, "give me a new mother every time." "She just seems-slow," Helen Crane said. "Nonsense. All babies are different. Some of them develop much more quickly than others." "That's what my mother says." Helen Crane laughed, looking a little bit ashamed. "I suppose you've got young Don all upset about the fact that his daughter is already six months old and hasn't yet begun to learn to dance?" "I haven't mentioned it to him. I suppose she's just so precious that I worry about her all the time." "Well, apologize to her right now," Miss Strangeworth said. "She is probably worrying about why you keep jumping around all the time." Smiling to herself and shaking her old head, she went on down the sunny street, stopping once to ask little Billy Moore why he wasn't out riding in his daddy's shiny new car, and talking for a few minutes outside the library with Miss Chandler, the librarian, about the new novels to be ordered and paid for by the annual library appropriation. Miss Chandler seemed absentminded and very much as though she were thinking about something else. Miss Strangeworth noticed that Miss Chandler had not taken much trouble with her hair that morning, and sighed. Miss Strangeworth hated sloppiness. Many people seemed disturbed recently, Miss Strangeworth thought. Only yesterday the Stewarts' fifteen-year-old Linda had run crying down her own front walk and all the way to school, not caring who saw her. People around town thought she might have had a fight with the Harris boy, but they showed up together, at the soda shop after school as usual, both of them looking grim and bleak. Trouble at home, people concluded, and sighed over the problems of trying to raise kids right these days. From halfway down the block Miss Strangeworth could catch the heavy scent of her roses, and she moved a little more quickly. The perfume of roses meant home, and home meant the Strangeworth House on Pleasant Street. Miss Strangeworth stopped at her own front gate, as she always did, and looked with deep pleasure at her house, with the red and pink and white roses massed along the narrow lawn, and the rambler going up along the porch; and the neat, the unbelievably trim lines of the house itself, with its slimness and its washed white look. Every window sparkled, every curtain hung stiff and straight, and even the stones of the front walk were swept and clear. People around town wondered how old Miss Strangeworth managed to keep the house looking the way it did, and there was a legend about a tourist once mistaking it for the local museum and going all through the place without finding out about his mistake. But the town was proud of Miss Strangeworth and her roses and her house. They had all grown together. Page 19 of 22 End of Section Three Miss Strangeworth went up her front steps, unlocked her front door with her key, and went into the kitchen to put away her groceries. She debated about having a cup of tea and then decided that it was too close to midday dinnertime; she would not have the appetite for her little chop if she had tea now. Instead she went into the light, lovely sitting room, which still glowed from the hands of her mother and her grandmother, who had covered the chairs with bright chintz and hung the curtains. All the furniture was spare and shining, and the round hooked rugs on the floor had been the work of Miss Strangeworth's grandmother and her mother. Miss Strangeworth had put a bowl of her red roses on the low table before the window, and the room was full of their scent. Miss Strangeworth went to the narrow desk in the corner and unlocked it with her key. She never knew when she might feel like writing letters, so she kept her notepaper inside and the desk locked. Miss Strangeworth's usual stationery was heavy and creamcolored, with STRANGEWORTH HOUSE engraved across the top, but, when she felt like writing her other letters, Miss Strangeworth used a pad of various-colored paper bought from the local newspaper shop. It was almost a town joke, that colored paper, layered in pink and green and blue and yellow; everyone in town bought it and used it for odd, informal notes and shopping lists. It was usual to remark, upon receiving a note written on a blue page, that so-and-so would be needing a new pad soon-here she was, down to the blue already. Everyone used the matching envelopes for tucking away recipes, or keeping odd little things in, or even to hold cookies in the school lunchboxes. Mr. Lewis sometimes gave them to the children for carrying home penny candy. Although Miss Strangeworth's desk held a trimmed quill pen which had belonged to her grandfather, and a gold-frosted fountain pen which had belonged to her father, Miss Strangeworth always used a dull stub of pencil when she wrote her letters, and she printed them in a childish block print. After thinking for a minute, although she had been phrasing the letter in the back of her mind all the way home, she wrote on a pink sheet: DIDN'T YOU EVER SEE AN IDIOT CHILD BEFORE? SOME PEOPLE JUST SHOULDN'T HAVE CHILDREN SHOULD THEY? She was pleased with the letter. She was fond of doing things exactly right. When she made a mistake, as she sometimes did, or when the letters were not spaced nicely on the page, she had to take the discarded page to the kitchen stove and bum it at once. Miss Strangeworth never delayed when things had to be done. After thinking for a minute, she decided that she would like to write another letter, perhaps to go to Mrs. Harper, to follow up the ones she had already mailed. She selected a green sheet this time and wrote quickly: HAVE YOU FOUND OUT YET WHAT THEY WERE ALL LAUGHING ABOUT AFTER YOU LEFT THE BRIDGE CLUB ON THURSDAY? OR IS THE WIFE REALLY ALWAYS THE LAST ONE TO KNOW? Miss Strangeworth never concerned herself with facts; her letters all dealt with the more negotiable stuff of suspicion. Mr. Lewis would never have imagined for a minute that his grandson might be lifting petty cash from the store register if he had not had one of Miss Strangeworth's letters. Miss Chandler, the librarian, and Linda Stewart's parents would have gone unsuspectingly ahead with their lives, never aware of possible evil lurking nearby, if Miss Strangeworth had not sent letters opening their eyes. Miss Strangeworth would have been genuinely shocked if there had been anything between Linda Stewart and the Harris boy, but, as long as evil existed unchecked in the world, it was Miss Strangeworth's duty to keep her town alert to it. It was far more sensible for Miss Chandler to wonder what Mr. Shelley's first wife had really died of than to take a chance on not knowing. There were so many wicked people in the world and only one Strangeworth left in the town. Besides, Miss Strangeworth liked writing her letters. She addressed an envelope to Don Crane after a moment's thought, wondering curiously if he would show the letter to his wife, and using a pink envelope to match the pink paper. Then she addressed a second envelope, green, to Mrs. Harper. Then an idea came to her and she selected a blue Page 20 of 22 sheet and wrote: YOU NEVER KNOW ABOUT DOCTORS. REMEMBER THEY'RE ONLY HUMAN AND NEED MONEY LIKE THE REST OF US. SUPPOSE THE KNIFE SLIPPED ACCIDENTALLY. WOULD DR. BURNS GET HIS FEE AND A LITTLE EXTRA FROM THAT NEPHEW OF YOURS? She addressed the blue envelope to old Mrs. Foster, who was having an operation next month. She had thought of writing one more letter, to the head of the school board, asking how a chemistry teacher like Billy Moore's father could afford a new convertible, but, all at once, she was tired of writing letters. The three she had done would do for one day. She could write more tomorrow; it was not as though they all had to be done at once. She had been writing her letters—sometimes two or three every day for a week, sometimes no more than one in a month—for the past year. She never got any answers, of course, because she never signed her name. If she had been asked, she would have said that her name, Adela Strangeworth, a name honored in the town for so many years, did not belong on such trash. The town where she lived had to be kept clean and sweet, but people everywhere were lustful and evil and degraded, and needed to be watched; the world was so large, and there was only one Strangeworth left in it. Miss Strangeworth sighed, locked her desk, and put the letters into her big black leather pocketbook, to be mailed when she took her evening walk. She broiled her little chop nicely, and had a sliced tomato and a good cup of tea ready when she sat down to her midday dinner at the table in her dining room, which could be opened to seat twentytwo, with a second table, if necessary, in the hall. Sitting in the warm sunlight that came through the tall windows of the dining room, seeing her roses massed outside, handling the heavy, old silverware and the fine, translucent china, Miss Strangeworth was pleased; she would not have cared to be doing anything else. People must live graciously, after all, she thought, and sipped her tea. Afterward, when her plate and cup and saucer were washed and dried and put back onto the shelves where they belonged, and her silverware was back in the mahogany silver chest, Miss Strangeworth went up the graceful staircase and into her bedroom, which was the front room overlooking the roses, and had been her mother's and her grandmother's. Their Crown Derby dresser set and furs had been kept here, their fans and silver-backed brushes and their own bowls of roses; Miss Strangeworth kept a bowl of white roses on the bed table. She drew the shades, took the rose satin spread from the bed, slipped out of her dress and her shoes, and lay down tiredly. She knew that no doorbell or phone would ring; no one in town would dare to disturb Miss Strangeworth during her afternoon nap. She slept, deep in t he rich smell of roses. After her nap she worked in her garden for a little while, sparing herself because of the heat; then she came in to her supper. She ate asparagus from her own garden, with sweet -butter sauce and a soft boiled egg, and, while she had her supper, she listened to a late evening news broadcast and then to a program of classical music on her small radio. After her dishes were done and her kitchen set in order, she took up her hat—Miss Strangeworth's hats were proverbial in the town; people believed that she had inherited them from her mother and her grandmother -and, locking the front door of her house behind her, set off on her evening walk, pocketbook under her arm. She nodded to Linda Stewart's father, who was washing his car in the pleasantly cool evening. She thought that he looked troubled. There was only one place in town where she could mail her letters, and that was the new post office, shiny with red brick and silver letters. Although Miss Strangeworth had never given the matter any particular thought, she had always made a point of mailing her letters very secretly; it would, of course, not have been wise to let anyone see her mail them. Consequently, she timed her. walk so she could reach the post office just as darkness was starting to dim the outlines of the trees and the shapes of people's faces, although no one could ever mistake Miss Strangeworth, with her dainty walk and her rustling skirts. There was always a group of young people around the post office, the very youngest roller-skating upon its driveway, which went all the way around the building and was Page 21 of 22 the only smooth road in town; and the slightly older ones already knowing how to gather in small groups and chatter and laugh and make great, excited plans for going across the street to the soda shop in a minute or two. Miss Strangeworth had never had any self-consciousness before the children. She did not feel that any of them were staring at her unduly or longing to laugh at her, it would have been most reprehensible for their parents to permit their children to mock Miss Strangeworth of Pleasant Street. Most of the children stood back respectfully as Miss Strangeworth passed, silenced briefly in her presence, and some of the older children greeted her; saying soberly, "Hello, Miss Strangeworth." Miss Strangeworth smiled at them and quickly went on. It had been a long time since she had known the name of every child in town. The mail slot was in the door of the post office. The children stood away as Miss Strangeworth approached it, seemingly surprised that anyone should want to use the post office after it had been officially closed up for the night and turned over to the children. Miss Strangeworth stood by the door, opening her black pocketbook to take out the letters, and heard a voice which she knew at once to be Linda Stewart's. Poor little Linda was crying again, and Miss Strangeworth listened carefully. This was, after all, her town, and these were her people; if one of them was in trouble she ought to know about it. "I can't tell you, Dave," Linda was saying—so she was talking to the Harris boy, as Miss Strangeworth had supposed—"I just can't. It's just nasty." "But why won't your father let me come around anymore? What on earth did I do?" "I can't tell you. I just wouldn't tell you for anything. You've got to have a dirty, dirty mind for things like that." "But something's happened. You've been crying and crying, and your father is all upset. Why can't I know about it, too? Aren't I like one of the family?" "Not anymore, Dave, not anymore. You're not to come near our house again; my father said so. He said he'd horsewhip you. That's all I can tell you: You're not to come near our house anymore." "But I didn't do anything." "Just the same, my father said . . ." Miss Strangeworth sighed and turned away. There was so much evil in people. Even in a charming little town like this one, there was still so much evil in people. She slipped her letters into the slot, and two of them fell inside. The third caught on the edge and fell outside, onto the ground at Miss Strangeworth's feet. She did not notice it because she was wondering whether a letter to the Harris boy's father might not be of some service in wiping out this potential badness. Wearily Miss Strangeworth turned to go home to her quiet bed in her lovely house, and never heard the Harris boy calling to her to say that she had dropped something. "Old lady Strangeworth's getting deaf," he said, looking after her and holding in his hand the letter he had picked up. "Well, who cares?" Linda said. "Who cares anymore, anyway?" "It's for Don Crane," the Harris boy said, "this letter. She dropped a letter addressed to Don Crane. Might as well take it on over. We pass his house anyway." He laughed. "Maybe it's got a cheque or something in it and he'd be just as glad to get it tonight instead of tomorrow." "Catch old lady Strangeworth sending anybody a cheque," Linda said. "Throw it in the post office. Why do anyone a favor?" She sniffled. "Doesn't seem to me anybody around here cares about us," she said. "Why should we care about them?" "I'll take it over anyway," the Harris boy said. "Maybe it's good news for them. Maybe they need something happy tonight, too. Like us." Sadly, holding hands, they wandered off down the dark street, the Harris boy carrying Miss Strangeworth's pink envelope in his hand. Miss Strangeworth awakened the next morning with a feeling of intense happiness, and for a minute wondered why, and then remembered that this morning three people would open her letters. Harsh, perhaps, at first, but wickedness was never easily banished, and a clean heart was a scoured heart. Page 22 of 22 She washed her soft old face and brushed her teeth, still sound in spite of her seventy-one years, and dressed herself carefully in her sweet, soft clothes and buttoned shoes. Then, coming downstairs and reflecting that perhaps a little waffle would be agreeable for breakfast in the sunny dining room, she found the mail on the hall floor and bent to pick it up. A bill, the morning paper, a letter in a green envelope that looked oddly familiar. Miss Strangeworth stood perfectly still for a minute, looking down at the green envelope with the pencilled printing, and thought: It looks l ike one of my letters. Was one of my letters sent back? No, because no one would know where to send it. How did this get here? Miss Strangeworth was a Strangeworth of Pleasant Street. Her hand did not shake as she opened the envelope and unfolded the sheet of green paper inside. She began to cry silently for the wickedness of the world when she read the words: LOOK OUT AT WHAT USED TO BE YOUR ROSES. Questions: Answer questions one, two and three based upon the first section of the story: 1. What first impression does Jackson create of Miss Strangeworth? List three details that support that impression. 2. What impression does the author create of the town? List details that support that impression. 3. What details suggest that things might not be as perfect as they seem. Answer question four based upon the second section of the story: 4. Make a list of the details that Miss Strangeworth notices about each person she meets. Then note the assumption that she draws from each detail. Answer question five based upon the third section of the story: 5. Explain fully why Miss Strangeworth feels compelled to write her letters. Then write your own explanation of why you think that she really writes the letters. Support both answers with quotations and examples from the story. 6. This is an excerpt from the full story that Jackson wrote. Write either a beginning to the story that would help us understand why Miss Strangeworth is the way that she is, or write an ending to the story. 7. “It isn’t fair.” In a few well-developed paragraphs (approximately one page in length), write about something that you’ve experienced or observed that made you feel, at least sometimes, that the statement “Life is unfair” is quite true. Be sure to describe the incident of situation clearly and persuasively to reinforce your point of view.