fgm-event - Dumi International Aid

advertisement

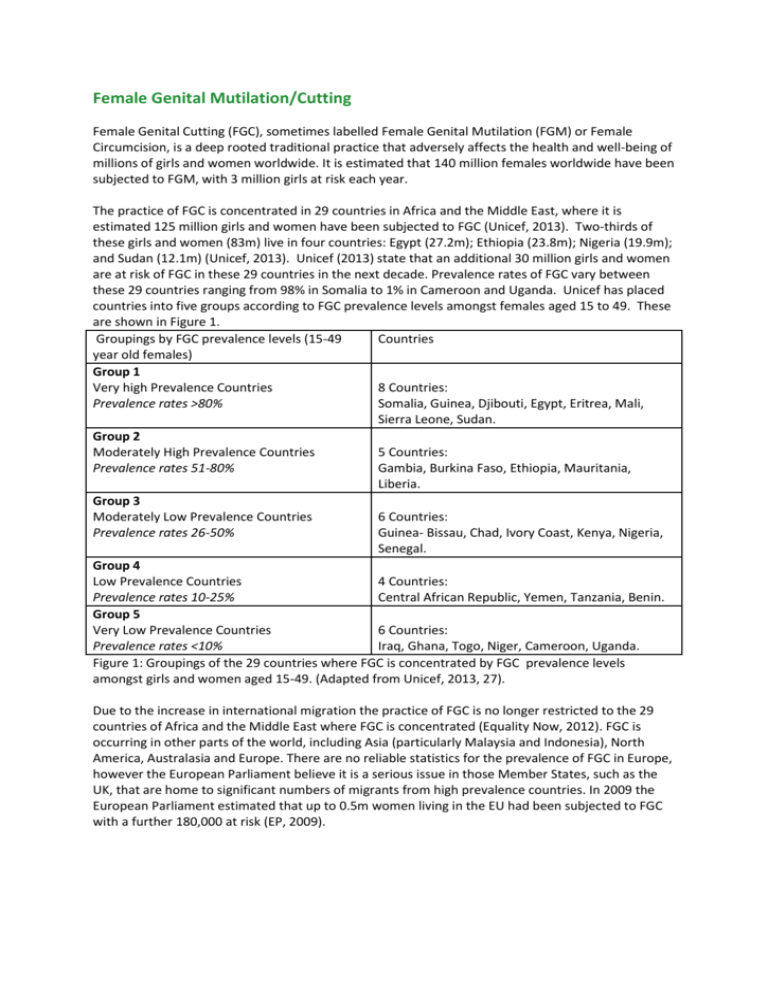

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Female Genital Cutting (FGC), sometimes labelled Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Circumcision, is a deep rooted traditional practice that adversely affects the health and well-being of millions of girls and women worldwide. It is estimated that 140 million females worldwide have been subjected to FGM, with 3 million girls at risk each year. The practice of FGC is concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, where it is estimated 125 million girls and women have been subjected to FGC (Unicef, 2013). Two-thirds of these girls and women (83m) live in four countries: Egypt (27.2m); Ethiopia (23.8m); Nigeria (19.9m); and Sudan (12.1m) (Unicef, 2013). Unicef (2013) state that an additional 30 million girls and women are at risk of FGC in these 29 countries in the next decade. Prevalence rates of FGC vary between these 29 countries ranging from 98% in Somalia to 1% in Cameroon and Uganda. Unicef has placed countries into five groups according to FGC prevalence levels amongst females aged 15 to 49. These are shown in Figure 1. Groupings by FGC prevalence levels (15-49 Countries year old females) Group 1 Very high Prevalence Countries 8 Countries: Prevalence rates >80% Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Mali, Sierra Leone, Sudan. Group 2 Moderately High Prevalence Countries 5 Countries: Prevalence rates 51-80% Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Liberia. Group 3 Moderately Low Prevalence Countries 6 Countries: Prevalence rates 26-50% Guinea- Bissau, Chad, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal. Group 4 Low Prevalence Countries 4 Countries: Prevalence rates 10-25% Central African Republic, Yemen, Tanzania, Benin. Group 5 Very Low Prevalence Countries 6 Countries: Prevalence rates <10% Iraq, Ghana, Togo, Niger, Cameroon, Uganda. Figure 1: Groupings of the 29 countries where FGC is concentrated by FGC prevalence levels amongst girls and women aged 15-49. (Adapted from Unicef, 2013, 27). Due to the increase in international migration the practice of FGC is no longer restricted to the 29 countries of Africa and the Middle East where FGC is concentrated (Equality Now, 2012). FGC is occurring in other parts of the world, including Asia (particularly Malaysia and Indonesia), North America, Australasia and Europe. There are no reliable statistics for the prevalence of FGC in Europe, however the European Parliament believe it is a serious issue in those Member States, such as the UK, that are home to significant numbers of migrants from high prevalence countries. In 2009 the European Parliament estimated that up to 0.5m women living in the EU had been subjected to FGC with a further 180,000 at risk (EP, 2009). It is known that FGC is practised in the UK (RCM, 2013). A study published in 2007, based on the UK 2001 Census, estimated that 66,000 women in England and Wales had undergone FGC and 23,000 girls under the age of 15 were at risk (Dorkenoo, Morison & Macfarlane, 2007). Another study, using the UK 2001 Census together with birth registration data from 1993-2004, suggests that over 98,376 girls under the age of 15 living in the UK have been subject to FGC or are at risk (Equality Now, 2012). These figures are, according to the Royal College of Midwives (2013, 10), ‘alarming’. The number of girls at risk of FGC in the UK is increasing as the births to women affected by FGC has increased from 1.04% in 2001 to 1.67% in 2008 (Equality Now, 2012; RCM, 2013). According to the Royal College of Midwives FGC is a hidden phenomenon in the UK with the numbers of girls and women affected by FGC increasing. FGC: definition and classification The WHO defines FGC as ‘all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.’ (WHO, 2008, 4). WHO recognise four types of FGC, which are described in Figure 2. Types I to III reflect increasing invasiveness of the cutting, whilst Type IV includes unclassified genital injuries where flesh is not removed but bleeding occurs. EndFGM (2010) estimate that globally, of females who have been affected by FGC, 90% have been subjected to Types I, II and IV, with 10% subjected to the more serious Type III which predominates in Sudan and Somalia. FGC Classification Type I Clitoridectomy Type II Excision Type III Infibulation Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce. Partial or total removal of the clitoris and labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora. Narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting and bringing together the labia minora and/or labia majora to create a type of seal, with or without the excision of the clitoris. All other harmful procedures to the female genitals for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, cauterisation. Type IV Symbolic Circumcision Figure 2: WHO classification of FGC (Adapted from WHO, 2008; Unicef, 2013) There is a range in the type of FGC performed in a selection of countries. Figure 3 shows the diversity of FGC performed within countries. For example, despite having FGC prevalence in excess of 90%, in Somalia 63% of girls under 15 have been subjected to FGC Type III, whereas in Djibouti the proportion is 30%. This illustrates the difficulties of using one term, FGC, to refer to the range of FGC practices. Country Type IV Types I and II Type III Benin Djibouti Eritrea Mali Nigeria Somalia Tanzania % of total FGC 2 15 52 16 16 5 1 % of total FGC 95 53 6 71 69 25 98 % of total FGC 2 30 38 3 6 63 2 FGC prevalence rate (15-49 years) 13 93 89 89 27 98 15 Figure 3: Percentage of girls who have undergone FGC, by type, as reported by their mother. (Compiled from Unicef, 2013). In the UK a recent study estimating the numbers of girls under 15 with or at risk of FGC indicates that all types of FGC are present in the UK (Equality Now, 2012). This study suggests that over 24,000 girls under the age of 15 have or are at risk of FGC Type III. A further 9,000 girls are at high risk of FGC Type I or II, with over 65,000 girls at low or medium risk of FGC (Figure 4). This study also highlights that over 80% of under 15 year old girls with or at risk of FGC have been born in England or Wales, with almost 72% of girls with or at risk of Type III having been born in England or Wales. British citizens and permanent residents are continuing to be victims of FGC, despite FGC being illegal in the UK since 1985, with an extraterritoriality clause added in 2003, making it illegal for a British citizen or permanent resident to have the procedure performed overseas. Countries by Unicef Born in country FGC Grouping Group 1 High risk of FGM 6,800 Countries Type III Born in England and Wales 17,212 Total 24,012 Group 1 and 2 countries High risk FGM Type I or II 1,972 6,941 8,913 Group 3 and 4 countries Medium risk FGM Type I or II 2,346 13,488 15,834 Group 4 and 5 countries Low risk FGM Type I or II 7,622 41,995 49,617 18,740 79,636 Total 98,376 Figure 4: Estimated numbers of girls aged under 15 living in England and Wales with or at risk of FGC and type of FGC. (Adapted from Equality Now 2012, 25). The EU frames FGC as domestic violence against females, a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against females. Most EU Member States have criminal legislation which defines the practice of FGC as an offence. Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK all have specific provisions associated with FGC. Other Member States address FGC under general criminal law, such as grievous bodily harm. Most also have an extra territoriality clause. However there have been few convictions in the EU indicating that the law is not enforced. FGC has been a criminal offence in the UK since 1985 under the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act which was replaced in 2003 by the Female Genital Mutilation Act (updated to address FGC performed on UK citizens and permanent residents outside the UK) with a maximum 14 years imprisonment penalty. To date there have been no prosecutions in the UK although three doctors have been found to have committed serious professional misconduct by the General and the Dental Medical Council in relation to FGC and have been struck off (RCM, 2013). UK law treats FGC as child abuse and as such frontline professionals, including doctors, nurses, teachers, social workers and others have a legal duty to protect girls from FGC. It is Local Safeguarding Children’s Boards which have the responsibility for developing inter-agency policies and procedures for safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children, which covers FGC. There is evidence that child protection guidelines are not being followed when girls affected by FGC are identified (RCM, 2013). In 2013 the NSPCC launched a national FGM helpline (0800 028 3550) for children at risk and as a point of reference for the public and professionals to report concerns. In the first three months of the setting up of the helpline, 102 enquiries were received and 38 referrals made to the police (RCM, 2013). This indicates a serious under-reporting of FGC in the UK, by those who have undergone or are at risk of the procedure, as well as those who encounter FGC professionally. References Barrett, H.R., Brown, K., Beecham, D., Otoo-Oyortey, N., & Naleie, S., 2011, Pilot toolkit for replacing approaches to ending FGM in the EU: implementing behaviour change with practising communities. REPLACE. Coventry university, Coventry. Cook, R.J., Dickens, B.M. & Fathalla, M.F., 2002, Female Genital Cutting (Mutilation/Circumcision): ethical and legal dimensions. International journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics, 79, 281-287. Dorkenoo, E., Morison, L, Macfarlane, A, 2007, A statistical study to estimate the prevalence of FGM in England and Wales. FORWARD, London. EndFGM, 2010, Ending Female Mutilation: a strategy for the European Union Institutions. EndFGM, Brussels. Equality Now, 2012, Female Genital Mutilation: Report of a research methodology workshop on estimating prevalence of FGM in England and Wales. 22-13 March 2012. Equality Now, London. European Parliament (EP), 2009, European Parliament Resolution on Combating FGM in the EU. 24th March 2009(2008/2071(INI)). EU Brussels. Morison, L., Scherf, C., Ekpo, G., Paine, K., West, B., Coleman, R., & Walraven, G., 2001, The longterm reproductive health consequences of Female Genital Cutting in rural Gambia: a communitybased survey. Tropical Medicine and International health, 6 (8), 643-653. Okonofua, F, 2006, FGM and reproductive health in Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 10 (2), 7-9. Population Reference Bureau (PRB), 2010, Female Genital mutilation/Cutting: data and trends. Available from : http://www.prb.org/pdf10/fgm-wallchart2010.pdf [accessed 3.2.11] Royal College of Midwives (RCM), 2013, Tackling FGM in the UK. Royal college of Midwives, London. Shaaban, L.M. & Harbison, S., 2005, Reaching the tipping point against FGM. The Lancet, 366, 347349. Toubia, N F & Sharief, E H, 2003, FGM: have we made progress? International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 82, 251-261. Unicef, 2007, Coordinated strategy to abandon Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in one generation. Unicef, New York. Unicef, 2010, Prevalence among women 15-49 as of 1st October 2010: Unicef global databases based on data from MICS, DHS and other national surveys, 1997-2009. Unicef, New York. Unicef, 2013, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. Unicef, New York. UNFPA, 2007, A holistic approach to the ababndonment of FGM/cutting. UNFPA, New York. UNFPA-Unicef, 2012, Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: accelerating change. Annual Report 2012. UNFPA-Unicef, New York. WHO, 1999, Female Genital Mutilation: Programmes to date. What works and what doesn’t. Department of Women’s Health, WHO, Geneva. WHO, 2000, A Systematic Review of the Health Complications of FGM. Department of Women’s Health, Family and Community Health, WHO, Geneva. WHO, 2006, FGM and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative study in six African countries. The Lancet, 367, 1799-1800. WHO, 2008, FGM WHO Fact Sheet 241. Available from: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/print.html [accessed 12.9.11] WHO, 2011, An update on WHO’s work on FGM: Progress Report. WHO, Geneva