Symposium Proposal Abstract The Why, Who and How of

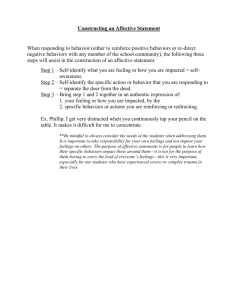

advertisement

Symposium Proposal Abstract The Why, Who and How of Identification in Organizations Organizations often wish to evoke high identification among their members. But what exactly do they wish to encourage? Organizational members can identify with different constituents of the organization (e.g., teams, leaders, colleagues). They may also identify with each in different ways (e.g., affectively, evaluatively, ideologically). Given its complex nature, it is crucial to explore the varied aspects of identification, in order to harness its benefits for the sake of the organization and its members. In the proposed symposium we seek to provide a comprehensive view on the concept of identification, by examining its motivational basis, content, structure, and outcomes. The first two presentations focus on motivational bases underlying identification with different constituents of the organization. First, Sverdlik and Rabin will present two studies conducted in a non-profit mentoring organization. They examined individual differences in values as predictors of identification: Whereas conformity and tradition (vs. self-direction) values were associated with affective organizational commitment, benevolence (vs. power) values were associated with positive affect towards the mentee (Study 1). In a longitudinal study (Study 2), mentor-supervisor value congruence was positively associated with organizational-related outcomes (e.g., affective organizational commitment), whereas mentor-mentee value congruence was positively associated with mentee-related outcomes (e.g., affective commitment towards the mentee). In the second presentation, Rechter and Higgins employed a multi-level design to examine the role of regulatory modes (i.e., assessment and locomotion) on team-athletes' positive affiliation with their leader. Athletes' assessment was negatively related to affiliation with the team leader, while locomotion was unrelated to it. Moreover, fit between athletes' and leaders' regulatory modes positively predicted affiliation with the leader: Athletes high on assessment (locomotion) affiliated more with leaders high on assessment (locomotion), and vice versa – athletes low on assessment (locomotion) affiliated more with leaders low on assessment (locomotion). Whereas the first two presentations focused on identification with current group constituents, the third presentation by Berlin and colleagues suggests that groups can also be represented as temporally continuous entities. Members differ in the extent to which they perceive their group to be composed of past and future generations versus current members only. Individuals whose perception of their ingroup includes past and future generations tended more to favor internal newcomers and reject external ones (Studies 1a & 1b). Furthermore, the perception of the group's inclusiveness affected attitudes towards public policy regarding environmental plans (Studies 2a & 2b). In the fourth presentation Elster, Sagiv, and Roccas examined the multidimensional structure of identification and its differential consequences to voice behavior. In a longitudinal field study conducted in a public university, the authors showed the differential effect of two modes of identification: The commitment mode (the affective component) positively predicted voice behavior, whereas the deference mode (the ideological component) predicted it negatively. These findings were consistent, both when identification modes and voice behavior were measured at the same time point, and when voice behavior was assessed two years later. The four presentations included in this symposium differ in the nature of studies (field and lab), methodology (correlational, longitudinal, multi-level designs) and context (non-profit organizations, sports teams). Taken together, the research included in this symposium provides new insights into a fundamental concept in organizational life – identification, by focusing on different aspects of it. Our joint contributions can be utilized by theoreticians and practitioners to manage and maintain positive relations between individuals and their organization. First Presentation Congruence between Personal Values and Perceived Expectations Predicts Affective Attachment to the Organization and Client Noga Sverdlik and Tali Rabin Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Employees' affective commitment may be directed towards various targets in the workplace such as the organization, the supervisor or the work group (e.g., Vandenberghe, Bentein, & Stinglhamber, 2004). Despite a growing interest in this phenomena there is still much to be learned about the antecedents of these various directions of commitment. In the present research we focus on the congruence between person's values and the environment. Values congruence is believed to be one of the primary bases for the developments of affective commitment (e.g., Meyer, & Herscovitch, 2001). Nevertheless, research on the relationship between value congruence and commitment largely overlooks the variability in targets of commitment (e.g., Greguras & Diefendorff, 2009). Our aim is to expand our knowledge on how values congruence with different organizational entities is related to affective commitment and emotions towards various targets in the workplace. In the present studies, we use Personal Values' theory (Schwartz, 1992) to link values and value congruence with different organizational entities (supervisor and client) to affective reactions (i.e., positive emotions and affective commitment) directed towards different targets. In two field studies in a non-profit mentoring organization (similar to the “Big Brothers Big Sisters” program in the US), we show that different values (Study 1) and different indicators of value congruence (Study 2) predict affective commitment and positive emotions towards the organization and towards the clients of the organization (i.e., the mentees). In Study 1, mentors (N = 84), reported their personal values, their level of organizational affective commitment and their level of positive emotions towards their mentee. We expected that the orientation towards the organization will be related to values that promote (conformity, tradition) versus hinder (self-direction) adherence to institutional authority. In addition, because of the nature of the mentors' role, we expected that the orientation towards the mentee will be related to values that promote (benevolence) versus hinder (power) concern for the welfare of others. As expected, different values predicted each of the two outcomes. Specifically, self-direction values were negatively related (r = -.45, p < .01), and conservation values were positively related (r = .22, p < .05), to organizational affective commitment. Power values were negatively related (r = -.30, p < .01), and benevolence values were positively related (r = .26, p < .05), to positive emotions towards the mentee. Study 2 (N = 62) was a longitudinal study in which we measured personal values, subjective value expectations from the supervisor, and subjective value expectations from the mentee (client), in Time 1. These measures served to calculate two types of values congruence indicators: (a) Mentor-supervisor expectations congruence, (b) Mentors-mentee expectations congruence. In Time 2, five to seven months later, participants reported their: (a) affective reactions (i.e., commitment and emotions) towards that organization and their clients and (b) organizational outcomes. We found (see Figure 1) that the two different indicators of person-environment values congruence predicted affective orientations towards different entities. In particular, person-supervisor expectations congruence predicted organizational commitment and positive feelings towards the organization, whereas person-mentee expectations congruence predicted positive feeling towards the mentee. These, in turn, predicted affective commitment towards the mentee. Furthermore, both types of commitment predicted intentions to remain in the organization as a mentor. However, only organizational commitment predicted the inspiration to become a supervisor and only commitment to the mentee predicted job satisfaction. Together Studies 1 and 2 show that the values framework enables a better understanding of different types of affective commitment, different types of emotional orientations and their role as mediators between values congruence and additional outcomes. References Greguras, G. J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). Different fits satisfy different needs: linking personenvironment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 465. Meyer, J. P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11(3), 299-326. Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (vol. 25, pp. 1-69). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 47-71. Figure 1.Model with standardized path coefficients. -.22* Mentorsupervisor value congruence .32** .49** Positive affect towards the organization .59** Affective organizational commitment .26 * Intentions to remain a mentor .35** .60** Promotion aspirations .32** Mentor-mentee value congruence .26* Positive affect towards the mentee .60** Affective reactions *p < .05, **p < .01 Affective commitment to the mentee .61** Job satisfaction Organizational outcomes Second Presentation Followers' Reactions to their Leaders: Regulatory Mode Congruence Eyal Rechter1 and Tory E. Higgins2 1 Ono Academic College and Columbia University 2Columbia University Effective self-regulation requires two basic components: assessment and locomotion. Assessment involves comparisons and evaluations of goals and means, while locomotion involves initiating and maintaining movement (Kruglanski et al., 2000). Individuals chronically differ in their emphasis of assessment and locomotion. Individuals with high assessment focus more on goals selection and the choice of appropriate means, to ensure making the right decisions. They tend to engage in deep, critical thinking, comparisons and evaluation. Individuals with high locomotion, on the other hand, prefer continuous movement and action, and are impatient with delays. The study of regulatory mode in organizational contexts is still a growing field, specifically when it comes to leadership. Kruglanski et al. (2007) found that employees' job satisfaction is related to fit between their regulatory mode and leadership style, with high assessment employees showing a preference for "advisory" style, and high locomotion employees showing a preference for "forceful" style. In a school context, Pierro et al. (2009) found that students' satisfaction from their teacher is related to fit between their regulatory mode and teaching climate, with high assessment students showing a preference for controlling climate, while high locomotion students showing a preference for autonomy promoting climate (Pierro et al., 2009). The current study focuses on the congruence of regulatory mode between leaders and followers. We examine both the simple effects of followers' regulatory mode, and the interactions between followers' and leaders' regulatory mode, on followers' affective reaction toward and satisfaction from their leader. Players (N = 207) and coaches (N = 30) from a women community sport organization in Israel participated in the study (90 players were paired with their coaches). Participants reported their regulatory mode, andplayers also reported their emotions toward and satisfaction from their coach, that were highly correlated and collapsed into a single measure. Results indicate that players' assessment is negatively related to favorable reaction to the coach (r = -.16, p < .05). Interactions between players' and coaches' regulatory mode were examined using hierarchical linear modeling. Results indicate the players' and coaches' assessment interact to predict positive reaction toward the coach (γ = 0.29, p < .05; see Figure 1), with high assessment players showing a preference for high assessment coaches, and low assessment players showing a preference to low assessment coaches. Players' and coaches' locomotion also interacted to predict positive reaction to the coach (γ = 0.96, p < .05; see Figure 2), with high locomotion players showing a preference for high locomotion coaches, and low locomotion players showing a preference for low locomotion coaches. The current results show that to better understand how regulatory mode is related to followers' attachment to their leaders, we need to consider the congruence between leaders and followers personality. References Kruglanski, A.W., Pierro, A. & Higgins, E.T. (2007). Regulatory mode and preferred leadership styles: How fit increases job satisfaction. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 137-149. Kruglanski, A. W., Thompson, E. P., Higgins, E. T., Atash, M. N., Pierro, A., Shah, J. Y., Spiegel, S. (2000). To "do the right thing" or to "just do it": Locomotion and assessment as distinct self-regulatory imperatives. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 79, 793-815. Pierro, A., Presaghi, F., Higgins, E.T., & Kruglanski, A.W. (2009). Regulatory mode preferences for autonomy supporting versus controlling instructional style. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 599-615. Figure 1: Interaction between players' and coaches' assessment to predict affective reaction 5.60 Low Coach Assessment Affective Reaction to Coach High Coach Assessment 5.47 5.35 5.22 5.09 -1.25 -0.64 -0.04 0.57 1.18 Players Assessment Figure 2: Interaction between players' and coaches' locomotion to predict affective reaction 5.56 Low Coach Locomotion Affective Reaction to Coach High Coach Locomotion 5.38 5.21 5.04 4.87 -0.99 -0.53 -0.07 0.38 Players Locomotion 0.84 Perceiving the Ingroup as Trans-Generational: Consequences of Differences in Temporal Representations of the Ingroup Avihay Berlin1, Sonia Roccas2, David Schiefer3, Yechiel Klar4, Katja Hanke3, and Klaus Boehnke3 1 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2The Open University of Israel, 3Jacobs University Bremen, 4Tel Aviv University Group members differ in the extent to which their mental representation of the ingroup includes past and future generations. Those who have a temporally-inclusive representation of the ingroup view it as Trans-Generational. Consequently, their sense of belonging and loyalty lies not only with current group members, but with all generations of the group that ever have and ever will exist. Previous research has shown that Trans-Generational Perception (TGP) of the ingroup is related to a tendency to give primacy to abstract and symbolic group interests over the concrete interests of its current generation (Kahn, Klar, & Roccas, 2014). However, this research was conducted exclusively within the context of severe intergroup conflict, and therefore it is yet unclear whether the concept of TGP is useful for explaining "peace-time" intragroup behavior. In the present studies we sought to further our understanding of TGP by exploring its relation with other forms of ingroup-protective behaviors: Studies 1a and 1b examined TGP's relation with readiness to integrate newcomers into the group. Studies 2a and 2b examined TGP's relations with attitudes toward public policies regarding environmentally hazardous development plans. Studies 1a and 1b: Newcomers who wish to join the group pose various threats to its assets, both concrete (e.g., consuming resources) and symbolic - by taking on the identity of the group. Existing members who perceive the group as trans-generational are likely to be highly protective of these assets, especially when deciding who should be granted the identity and access to the group. We thus hypothesize that those high on TGP are likely to favor (internal) newcomers who share some common essence of the group (e.g., repatriates), over those (external) who have no such links to it (e.g., immigrants). German (N = 155) and Israeli (N = 147) citizens participated in Studies 1a and 1b, respectively. Participants were randomly assigned to an internal vs. external newcomers condition. They first reported their TGP and then their attitudes toward newcomers. A subsample of 96 Israeli participants also ranked the importance of different criteria for granting newcomers access to the group (e.g., shared ethnicity, assimilation, contribution). As hypothesized, in both studies a significant interaction effect emerged between TGP and Newcomer-Type on attitudes (β1a = -.17, p1a < .05, ΔR21a = .03; β1b = -.18, p1b < .01, ΔR21b = .03): TGP led to greater origin-based distinctions between newcomers. Specifically, in both studies TGP was negatively associated with attitudes toward external newcomers (r1a = -.34, p1a < .001; r1a = .21, p1a < .07). In contrast, TGP was unrelated to attitudes toward internal newcomers in Study1a, whereas in Study 1b TGP was positively associated with attitudes toward internal newcomers (r = 23, p < .05). Furthermore, TGP was associated with greater support for ethnicity-based criteria for inclusion in the group versus all other criteria (F(3,282) = 4.04, p < .05). Studies 2a and 2b: Here we sought to extend previous findings on concrete-asset protection (e.g., territory, human and material resources), to the realm of environmental assets. In addition, we wanted to explore long-term focus as the mechanism explaining the TGP protective syndrome. Participants (N2a = 59, N2b = 147) first reported their TGP. They then read a description of two environmentally hazardous development plans emphasizing short-term (suggested by the Transportation Ministry, TM) and long-term (suggested by environmental organizations, EO) benefits, rated the plans' desirability, and evaluated their long-term benefits. The higher participants were on TGP, the more desirable they found the EO plan (r2a = .35, p2a < .01; r2b = .25, p2b < .01). No such relations were found with TM plan desirability. Moreover, focus on long-term mediated these relations (Figures 1 & 2). Taken together, the findings show that different temporal representations of the ingroup affect members' inclinations for protecting its symbolic and concrete assets. Our research extend previous findings by showing that intergroup conflict is not a necessary precondition for such a protective stance. References Kahn, D., Klar, Y., & Roccas, S. (2014). For the sake of the eternal group: Perceiving the group as a Trans-Generational Entity and Endurance of Ingroup Suffering. Unpublished manuscript. Long-Term Benefits * *** 0.32 TGP 0.75 EO Plan Evaluation ** 0.42 (0.19, n.s) Figure 1. Mediation Model for the Effect of TGP on EO Evaluation, Mediated by EO Long-term Benefits, in Study 2a Note .Values are unstandardized regression weights. Indirect effect = 0.24, Z = 2.15, p < .05, 95% CI [0.03, 0.53]. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Long-Term Benefits * *** 0.22 TGP 0.70 ** EO Plan Evaluation * 0.26 (0.14 ) Figure 2. Mediation Model for the Effect of TGP on EO Evaluation, Mediated by EO Long-term Benefits, in Study 2b Note. Values are unstandardized regression weights. Indirect effect = 0.12, Z = 2.04, p < .05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.24]. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Fourth Presentation The Differential Effect of Identification Modes on Voice Behavior in Organization Andrey Elster, Lilach Sagiv, and Sonia Roccas Identification with organizations has been studied extensively (see Riketta, 2005 for a metaanalysis). It has been associated with variables crucial to organizational striving, such as job satisfaction, intentions to leave, in-role and extra-role performance. There is a growing consensus among researchers that identification is a multi-dimensional construct (e.g., Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004). Little is known, however, on the different ways in which dimensions, or modes of identification, affect groups and organizations. In the current project we aim to fill this gap by focusing on two aspects of identification and studying their differential, even opposing, implications for voice behavior – "behavior that emphasizes expression of constructive challenge with an intent to improve the organization" (Van Dyne & LePine, 1998, p. 109). Specifically, in a two-year longitudinal study, we investigate how commitment (an affective aspect of identification) and deference (an ideological aspect of identification) differ in their implications for voice behavior in the organization. Commitment identification reflects the wish to contribute to the organization and its members. Commitment should therefore lead employees to act in ways that benefit the organization, even actions that challenge the organization and require change or alteration of its policies and practices. We thus hypothesize that commitment will positively predict voice behavior. In contrast, deference identification reflects glorification of the organization, and an unquestioning, respectful positive regard to the organization’s leadership and symbols. Deference should therefore hinder activities doubting the existing organizational course of action and undermining its policies. We thus hypothesize that deference will negatively predict voice behavior. Method. The data were collected as a part of a multi-wave satisfaction survey conducted among faculty members of a public university in Israel. We measured identification with the university and voice behavior at time 1 (n = 604) and measured voice behavior once again two years later (n = 483). As part of the survey, the participants were presented with open questions in which they were asked to comment and make suggestions regarding various topics (e.g., If you could make one change in the university what would you change?). To assess the voice behavior for each participant we summed the number of comments written at each wave. We measured the commitment and deference modes of identification with 3 items from the CIDS scale (Roccas et al., 2008) adapted for the current research. Results. To test our hypotheses we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis predicting the number of comments written at each time point while controlling for gender, academic rank, and whether or not the participants specified the department and faculty to which they belong. As hypothesized, commitment mode positively predicted voice behavior measured at time 1 (β = .18, t(596) = 4.21, p < .001) whereas deference mode predicted it negatively (β = -.18, t(596) = -4.30, p < .001). Moreover, similar results were obtained even when voice behavior was measured two years later at time 2 (commitment: β = .14, t(221) = 1.89, p = .06; deference: β = -.16, t(221) = -2.25, p < .05). Conclusions. Our findings indicate that organizational members who identify through different modes react differently to opportunities for organizational change. Thus, organizations aiming to evoke high identification among their members should carefully consider the specific identification mode they may encourage, bearing in mind their differential implications for organizational behavior. References Ashmore, R. D., Deaux, K., McLaughlin-Volpe, T. (2004). An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 80-114. Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 358-384. Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108-119. Table 1. The Regression Results for Predicting Voice Behavior by Identification Modes Voice behavior at Time 1 Voice behavior at Time 2 β t p β t p -.13 -3.06 .002 -.24 -3.50 .001 .01 0.21 .831 -.13 -1.62 .106 .09 1.90 .058 .00 0.03 .973 D full professor .05 0.90 .371 -.11 -1.35 .180 D specified -.19 -4.83 .001 -.11 -1.72 .086 R2 .059 Step 1: Control Variables D gender D assistant professor without tenure D assistant professor with tenure Step 2: Independent Variables Commitment .18 at Time 1 Deference -.18 at Time 1 .076 4.21 .001 .14 1.89 .060 -4.30 .001 -.16 -2.25 .025 ∆R2 .039 .027 N 604 221 Note. The controls were measured at the same time point as the voice behavior and were coded as dummy variables.