The Assassination and Funeral of President Abraham Lincoln: A

advertisement

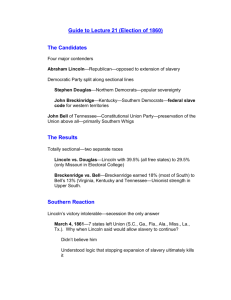

The Assassination and Funeral of President Abraham Lincoln: A Nation Mourns Its Slain Leader At 8:00 on Friday morning, April 21, 1865, the body of Abraham Lincoln, sixteenth president of the United States, departed from the Washington Depot in the funeral car of a special train to arrive in Springfield, Illinois thirteen days later. The train followed a circuitous route, stopping at major cities and state capitals of the eastern and mid-western United States, including Baltimore, Harrisburg, New York, Albany, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, and Chicago, before arriving home in Springfield, Illinois, where the President’s body was laid to rest. Thousands of mourners gathered by the wayside to glimpse a view of the president’s funeral car. How had a President, who had served the Nation, little more than four years, leading it into and through a costly Civil War, gained such devotion from its citizenry? Copy of Lithograph from the 1865 Illustrated Life, Services, Martyrdom, and Funeral of Abraham Lincoln. Sixteenth President of the United States. With a Portrait of President Lincoln, and other Illustrative Engravings of the Scene of the Assassination In his re-election campaign of 1864 President Lincoln demonstrated his War leadership with a combination of resolve and compassion. He struck a somber chord in an address at a United States Sanitary Commission fair at Logan Square in Philadelphia. Speaking about the War, he proclaimed that, “War at its best, is terrible, and this war of ours, in its magnitude and its duration, is one of the most terrible. It has deranged business, totally in many localities, and partially in all localities. It has destroyed property, and ruined homes; it has produced a national debt and taxation unprecedented, at least in this country. It has carried mourning to almost every home, until it can almost be said that the ‘heavens are hung in black.’” Little did he realize that the War would take a personal toll on his own house, costing Abraham Lincoln his life and making his wife a widow. No one anticipated the dire consequences yet to come. Instead, the autumn of 1864 brought good news for Lincoln and the Union. September, 1864 witnessed the fall of Atlanta. Two months later President Lincoln and his running mate, Andrew Johnson, won re-election by over 400,000 votes. On March 4, 1865 Lincoln was inaugurated for a second term. In his inaugural address he hoped and “fervently” prayed that the “scourge of war would speedily pass away.” Yet, if God willed it to continue, “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword,” Lincoln willingly accepted this as God’s righteous judgment. So, “With malice toward none, with charity toward all, with firmness in the right,” he urged his countrymen to “strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the Nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve . . . a just and a lasting peace.” Bold in his pursuit of victory, President Lincoln went to the front to witness the assault on Petersburg, Virginia and was nearby when Richmond fell on April 2. The fall of Richmond was followed by the surrender of General Robert E. Lee a week later at Appomattox Court House. After the President’s return to Washington, there was joy and celebration throughout the Capital. Monday evening, April 17 was proclaimed “a night of illumination,” when every loyal household in the country hung flags and portraits of their heroic warriors, lighting candles, lamps and bonfires to celebrate the peace. That day Mr. Lincoln was “unusually cheerful,” members of his Cabinet remarking that it appeared “that the great burden which had been weighing so heavily upon his spirits for the four years previous, was at last lifting from his breast.” The Assassination and Death of President Abraham Lincoln That evening Mr. Lincoln was invited to visit Ford’s Theater to see a performance of Our American Cousin. Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant was also present. President and Mrs. Lincoln reached the theater around 9:00 PM. Before the performance Lincoln bowed repeatedly to the audience from his box, as they cheered and waved their handkerchiefs and hats. It was a proud moment. About 10:00 PM as the play progressed, a stranger, later identified as the noted actor John Wilkes Booth, made his way to the proscenium box where the President and Mrs. Lincoln sat. He leveled a pistol close behind Lincoln’s head and fired, launching the ball deep into Lincoln’s brain. The assassin then drew a dagger and waving it about, he sprang to the stage exclaiming Virginia’s motto, “Sic Semper Tyrannis!” Before the actors or the audience realized what had taken place, the murderer stole out of a rear exit into an alley, where a horse awaited. Mrs. Lincoln’s screams first alerted the audience to the fact that the President had been shot. Many persons rushed to the President’s box. Some cried for others to “Stand back! [And] Give him fresh air!” Others called for stimulants. At first, those around him did not realize he was wounded. Some thought he was shot through the heart, but after removing his vest, and finding no wound, they discovered that he had been shot in the back of the head. After a few moments he was taken to a private house across the street from the theater, where he was attended to by the Surgeon-General. Several other prominent physicians and surgeons were also summoned. Gathered round him were Secretaries Stanton, Welles, Usher, McCullough and Attorney-General Speed together with House Speaker Schuyler Colfax. All night long the party held vigil around the couch of the dying President. Several times Lincoln’s son Captain Robert Lincoln and Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd entered the room, but, grief-stricken, they stayed only a short while. Friends encouraged them to remain in an adjoining room. From the moment he was shot, Lincoln never regained consciousness. As morning dawned, his pulse began to fail, and his breathing became labored. At 7:22 A.M. he quietly passed away. After the President’s death, his body was borne to the Executive Mansion in a hearse, and wrapped in an American Flag. A crowd of mourners accompanied the body to the White House, but a military guard allowed in only members of the household and personal friends. Lincoln’s body was laid out in the guest’s room in the northwest wing of the White House, dressed in a suit of black clothes that he had worn for his second inauguration. The Fate of John Wilkes Booth In the meantime, Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth, a Maryland native of Harford County, had escaped to St. Mary’s County, where he lay hidden for a number of days. Despite a reward of over $100,000 for his capture, he eluded his pursuers until Sunday, April 23, when parties of cavalry under Government Detective Colonel L.C. Baker discovered that Booth and an accomplice, David Herold, had crossed the Potomac into the neighborhood of Swann Point, Maryland. The next day Lieutenant Edward Doherty with a detachment of the 16th New York Cavalry, accompanied by Baker’s detectives took a steamer to Belle Plain. On Tuesday, April 25 they arrested a man named Jett, who had ferried the two conspirators across the Rappahannock River. Under pressure, Jett led the party to the farm of Mr. Garrett, about three miles from Port Royal, where Booth and Herold had ridden from the ferry. Doherty’s cavalry surrounded the barn, and talked to Booth and his accomplice for three hours, trying to convince them to surrender. Doherty received a report that southern sympathizers were gathering, and decided to burn out the conspirators. After the soldiers set fire to the barn, Herold surrendered, but Booth refused and prepared to fire. Instead, he was shot in the head by Sergeant Boston Corbett, and died two and a half hours later. Lincoln’s Funeral and National Mourning for the Slain President The Cabinet decided that funeral services for the late President would be held on Wednesday, April 19, two days after the assassination. Secretary of State William Hunter announced the funeral ceremonies would be held in the White House at noon. He invited churches from the Nation’s various religious denominations to observe the mournful occasion with worship services at that hour. Tuesday, April 18 was set aside for American citizens, regardless of rank, to pay their respects to the body of Mr. Lincoln, and fully 20,000 did so. The following day the nation’s capital was steeped in mourning. All of the stores were closed. Public buildings were draped in black, and every house in the city had hung a black crape on the door. Although attendance at the funeral was limited by invitation, already by 10:30 AM it became impossible to navigate the crowd of mourners. In the center of the East Room Lincoln’s coffin lay on a catafalque, surrounded by a large wreath of white camellias, orange blossoms and evergreens. On the east side of the casket were the President and Cabinet; on their right the Diplomatic Corps, Governors, the Judiciary, and representatives of the Army and Navy. To the left were the Supreme Court, Senators, Representatives, the Illinois and Kentucky delegations, the clergy and the Washington City authorities. On the west side were members of the Press. The funeral service was an ecumenical one. Bishop Simpson of the Methodist Episcopal Church led the audience in a fervent prayer. The Rev. Dr. Gurley, Pastor of the Presbyterian Church that the Lincolns attended in Washington preached an eloquent funeral oration. He concluded with the words of Tacitus, “You are blessed, not only because your life was a career of glory, but because you were released when your country was safe.” Baptist minister, the Rev. Dr. Gray closed the service with a prayer. Then the coffin was closed and carried out by twelve sergeants of the Veteran Reserve Corps. Following the funeral there was a solemn procession up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol. It was comprised of a military escort, including officers from the Cavalry, Artillery, the Marines, Army and Navy; a civic procession with clergy and pall bearers from the House and Senate, and the family, accompanied by delegations from Illinois and Kentucky. These were followed by the President, the Cabinet, representatives of Congress, the Judiciary, delegations from various states, the Officers of the Sanitary Commission, as well as any other societies who wished to join the procession. The column reached the Capitol by 3:00 P.M.. The coffin was borne into the Rotunda and an Honor Guard was assigned for several hours in the afternoon and evening. Lincoln’s body lay in state in the Capitol on Thursday with thousands of visitors coming to pay their respects. The Long Journey Home to Springfield At 7:00 A.M. on Friday Lincoln’s coffin was taken to the Washington Train Station to begin the long journey back to Springfield, Illinois. The coffin was deposited in a special funeral car. Cabinet members Edwin Stanton, Gideon Welles, Hugh McDulloch and Jonathan P. Usher, and Lieutenant General U.S. Grant and General M.C. Meigs accompanied the body. A special train was provided for the occasion, the route to Springfield designated by the War Department. Stops were scheduled as follows: Baltimore, April 21, 10:00 A.M.-3:00 P.M. Midnight A.M. A.M.-April 25, 4:00 P.M. April 25,11:00 P.M.- April 26, 4:00 P.M. York, April 27, 7:00 A.M.-10:10 A.M. Ohio, April 28, 7:00 A.M.-12:00 Midnight A.M.-8:00 P.M. 30, 7:00 A.M.-12:00 Midnight A.M.-May 2, 9:30 P.M. May 3, 8:00 A.M. Harrisburg, April 21, 8:20 P.M.-12:00 Philadelphia, April 22, 4:30 P.M.-4:00 New York, April 24, 10:00 Albany, New York, Buffalo, New Cleveland, Columbus, Ohio, April 29, 7:30 Indianapolis, Indiana, April Chicago, Illinois, 11:00 Springfield, Illinois, At various points along the route Lincoln’s remains were borne by State and municipal authorities in a hearse to receive public honors. The train proceeded no faster than twenty miles an hour to guard against any accident. Thousands of mourners gathered by the wayside to catch a glimpse of Lincoln’s passing funeral car. The funeral train arrived in Philadelphia 4:30 P.M. on the second day of the journey. It reached the Baltimore depot at Broad and Washington Streets, where tens of thousands of Philadelphians—men, women and children--had been waiting for hours. The procession moved east toward Independence Hall. Arriving at the Walnut Street entrance, the coffin was carried into Independence Hall and placed on an oblong platform in the center of the building just opposite the “Old Independence Bell”. The lid of the coffin was removed far enough to expose Lincoln’s face and breast. At the head of the casket was a cross made of japonicas with a center consisting of black exotics. The inscription below it read “To the memory of our beloved President, from a few ladies of the United States Sanitary Commission.” It had been decided that Lincoln’s remains would reside in Independence Hall on Sunday, April 23. Beginning at 6:00 in the morning a double line of mourners formed to file past the casket. The line extended as far west as Eighth Street and as far east as Third Street. By 11:00 A.M. the lines extended as far west as the Schuykill River and as far east as the Delaware. Throughout the day and night, until 1:00 in the morning, mourners came to pay their respects. Finally, at 3:00 A.M., the funeral train departed Philadelphia for New York City. In the following days it would travel to Albany, Syracuse, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, and Chicago, before its terminus in Springfield, Illinois on May 1. Lincoln’s funeral in Springfield occurred on May 4. At noon there was a twenty-one gun salute to the fallen leader, after which Lincoln’s body was taken from the Illinois State House, where he lay in state. A chorus of hundreds of voices accompanied a brass band, singing, “Children of the heavenly King, Let us journey as we sing.” The funeral procession was under the direction of Major-General Hooker, Marshal-in-chief, Brigadier-General Cook and Brevet Brigadier-General Oaks. The procession was viewed by immense crowds of people stretching for several miles. The procession arrived at the Oak Ridge Cemetery at 1:00 P.M. The President’s Pastor, Rev. Dr. Gurley, led the graveside service that began with the singing of a hymn. Methodist Bishop Simpson delivered the funeral oration. After a final hymn, Dr. Gurley pronounced the benediction. The solemn procession reformed and returned to the Capitol, leaving behind the remains of the sixteenth president. The American Nation felt a deep sense of loss, as they mourned their fallen President. Millions of Americans had glimpsed Lincoln’s funeral train on its way home. Others were fortunate enough to file past the casket in one of the cities along the way. Regardless of class, race, religion or political affiliation, “all hearts seemed to beat as one at the bereavement.” The preceding account of the assassination and funeral of President Abraham Lincoln comes from a contemporary volume on the Illustrated Life, Services, Martyrdom, and Funeral of Abraham Lincoln. Sixteenth President of the United States . With a Portrait of President Lincoln, and other Illustrative Engravings of the Scene of the Assassination. Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson & Brothers, 1865. This small volume from the State Library’s “transitionally” rare collection transports 21st century readers into the past to experience some of the shock and sense of loss that gripped the nation. The Rare Collections Library is open to students and researchers by appointment, Monday-Friday, between the hours of 9:00 am and 12:00 noon, and 1:00 pm-4:00 pm. To make an appointment, contact Dr. Iren Snavely by telephone at 717.783.5982, or by email at: irsnavely@pa.gov. The Rare Books reading room is also open periodically for tours to the general public and to Pennsylvania Commonwealth employees.