Disability in the Medieval Period 1050

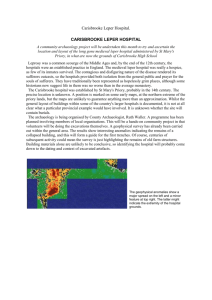

advertisement

R20 Teachers’ notes - Disability in the Feudal and Medieval Period Disability in the Medieval Period 1050 - 1485 This section describes the life of people with disabilities in the medieval period. It also explains how monasteries and convents cared for sick and disabled people and became the hospitals we use today. In the feudal and medieval period, most disabled people were accepted as part of the family or group, working on the land or in small workshops. But at times of social upheaval, plague or pestilence, disabled people were often made scapegoats as sinners or evil people who brought the disasters upon society. In medieval Europe the church took control of discussions about illness and disability. The Church’s interest in people with impairments was based on Jesus’ role as a miraculous healer and spiritual ‘physician’; maybe Jesus’ institutional representatives in the church monasteries were hoping optimistically for recovery. This belief was regularised by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215;“Since bodily infirmity is sometimes caused by sin, the Lord saying to the sick man who he had healed ‘Go and sin no more, lest some worse thing happen to thee’(John 5:14)we declare in the present decree and strictly command that when physicians of the body are called to the bedside of the sick, before all else they admonish them to call for the physician of the soul, so that spiritual health has been restored to them, the opportunities of bodily medicine may be of greater benefit, for the cause being removed, the effect will pass away.”1 The caring for the sick and disabled in Monasteries and Abbeys by the clergy across Europe in the medieval period has its roots in such declarations and the concept of charity. In medieval society there was a very fixed order, with each person knowing their place, and there was general hostility to those who did not have a place in that order, be they immigrants, beggars or disabled people. This horror of becoming disfigured or different was extremely powerful. If you were different you were somehow marked and this strong prejudice continues to the present day. 'William heals a blind woman' York Minster© English Heritage http://www.englishheritage.org.uk/content/images/disability-history/williamheals-a-blind-woman.jpg In medieval England, the 'lepre' (leaper), the 'blynde' (blind), the 'dumbe' (dumb), the 'deaff (deaf)', the 'natural fool' (people with learning difficulties), the 'creple' 1 Wheatley, E.(2010) ‘Stumbling Block Before the Blind: Medieval Construction of Disability’ Michigan University Press p10. http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=915892 (cripple), the 'lame' and the 'lunatick' (lunatic) were a highly visible presence in everyday life. People could be born with impairment, or become disabled by diseases such as leprosy or years of backbreaking work. Attitudes to disability were mixed. Some people thought it was a punishment for sin or the result of being born under the hostile influence of the planet Saturn. Others believed that disabled people were closer to God - they were suffering purgatory on earth rather than after death and would get to heaven sooner. Irene Metzler who has studied in detail this part of medieval history suggests a transition from cures by Saints around 1000 AD to an increased emphasis on the power of priests leading to a decline in accounts of healing miracles and a growth in religious mysticism. One reaction to this was that during times of plague thousands of people, called flagellants, wandered around Europe beating themselves to try to make themselves more 'holy' so they didn't get the plague. This self-imposed injury also spiritually downgraded those born with impairment or those who acquired their impairment randomly through disease or accident. It was believed that if you were penitent you would not become ill or disabled. Provision and care There was no state provision for people with disabilities. Most lived and worked in their communities, supported by family and friends. If they couldn't work, their town or village might support them, but sometimes people resorted to begging. They were mainly cared for by monks and nuns who sheltered pilgrims and strangers as their Christian duty. Care for sick and disabled people was based on the Church's teachings. The monks and nuns would follow the seven 'comfortable works' which involved feeding, clothing and housing the poor, visiting them when in prison or sick, offering drink to the thirsty, and burial. The seven 'spiritual works' included counsel and comfort for the sick. For further information please see Appendix 5 for links. Acting for themselves We know that disabled people made pilgrimages on foot to holy sites such as the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury in search of a cure or relief. Sometimes disabled people had to battle injustice. In 1297 the residents of the leper house in the Norfolk village of West Somerton mutinied against the thieving abbot and his men, looting and demolishing the buildings and killing the guard dog. First Hospitals Over this period a nationwide network of hospitals based in (or near) religious establishments began to emerge. Specialised hospitals for leprosy, blindness and physical disability were created. England's first mental institution, later known as 'Bedlam', was originally the Bethlehem hospital in the City of London (1247). It was a hospital (place of refuge) from the beginning 'originally intended for the poor suffering from any ailment and for such as might have no other lodging, hence its name, Bethlehem, in Hebrew, the "house of bread". At the same time, almshouses were founded to provide a supportive place for the disabled and elderly infirm to live. See Appendix 5 for more information. The Medieval Legacy The people, religious institutions and towns and cities of the medieval period were pioneers in terms of providing a specialised response to disability. Only a small number of their buildings remain, but over the next 500 years their early professional approach would eventually develop into our modern system of public services. In the 15th century, black magic and evil forces were felt to be ever-present. Martin Luther, founder of Protestantism, speaking of congenitally impaired children, said: “Take the changeling child to the river and drown them”. In 16th century Holland, those who caught leprosy were seen as sinners and had all their worldly goods confiscated by the State so they had to be supported by the alms of those who were not stricken. If these penitent sinners were humble enough, it was believed their reward was heaven after they died. The time of Leprosy: 11th Century to 14th Century This section explains how leprosy became endemic in England by the 11th century, and describes medieval attitudes towards the disease and how sufferers were cared for in religious houses and hospitals. A leper begging for alms from the margins of an English Pontifical c 1425 MS Lansdowne 451, fo 127r© British Library The Spread of Leprosy During the medieval period, leprosy's disabling consequences became very visible in all communities across England - rural and urban, rich and poor. Its impact would change both the landscape of the country and the mindset of its people. Chapel of St Mary Magdalen, Stourbridge, near Cambridge Leprosy had entered England by the 4th century and was a regular feature of life by 1050. Known today as Hansen's disease, in its extreme form it could cause loss of fingers and toes, gangrene, blindness, collapse of the nose, ulcerations, lesions and weakening of the skeletal frame. Enduring Purgatory on Earth Reaction to the disease was complicated. Some people believed it was a punishment for sin, but others saw the suffering of lepers as similar to the suffering of Christ. Because lepers were enduring purgatory on earth, they would go directly to heaven when they died, and were therefore closer to God than other people. Those who cared for them or made charitable donations believed that such good works would reduce their own time in purgatory and accelerate their journey to heaven. A stained glass depiction of Elias the leprous monk, Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral © Annaliza Gaber Leper Houses and Hospitals The earliest known example of a leper hospital is thought to be St Mary Magdalen in Winchester, Hampshire where burial excavations found evidence of leprosy. The remains were radiocarbon-dated to between 960 and 1030 AD. At least 320 religious houses and hospitals for the care of lepers (known as leper or 'lazar' houses) were established in England between the end of the 11th century and 1350. The houses were usually built on the edge of towns and cities, or if they were in rural areas, near crossroads or major travel routes. Lepers needed to stay in contact with society to beg alms, trade items, and offer services such as praying for the souls of benefactors. There was high demand for places in leper hospitals, and 'leprous brothers and sisters' were often accepted fully into the religious order of the house. Many of the buildings have decayed or were destroyed during Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. Some remain however, including the oldest - St Nicholas Harbledown in Canterbury, Kent (1070s) - St Mary Magdalene in Stourbridge near Cambridge, St Mary & St Margaret in Sprowston, Norwich, Norfolk and the hospital of St Mary the Virgin in Ilford, Greater London. Others survive as ruins or archaeological sites. The courtyard and 14th century almshouses at St.Cross Hospital, Winchester. The porch on the right leads to the kitchen and Bretherens Hall.© English Heritage Physical and Spiritual Care Care in religious leper houses centred as much on a person's spiritual needs as on their physical problems. Most hospitals consisted of a group of cottages built around a detached chapel where praying and singing continued throughout the day. Excavations at St Mary Magdalen in Winchester suggest that its chapel had a master's hall attached at right angles, with cells for the inmates built around the inside of the enclosure wall. The existing chapel at Harbledown in Kent has a sloping floor, perhaps so the floor could be washed after the lepers had attended mass. Life and Work in the Leper Hospital The emphasis was on cleanliness and wholesome food - clothes were washed twice a week and a varied diet was supplied if possible, often from the house's own fields and livestock. The therapeutic effect of horticultural work and the beauty of nature were recognised many houses had their own fragrant gardens of flowers and healing herbs, and residents took part in their upkeep. Many lepers stayed in touch with their family and friends and were allowed to make visits home and receive visitors. Leprosy in Retreat Attitudes began to change in the 14th century, particularly after the horrors of the Black Death (1347-1350). Fear of contagion led to greater restriction and isolation, while abusive and corrupt practices increased. But leprosy was in retreat - possibly due to greater immunity in the population - and many houses fell into disuse or were put to new uses. St Mary Magdalen in Ripon and the hospital of St Margaret and St Sepulchre in Gloucester both became almshouses for the sick and disabled poor. The impact of leprosy lived on - it had brought about an institutional response to disability in the form of buildings and methods of care which would strongly influence future generations.