Suggested Databases: Google Scholar

advertisement

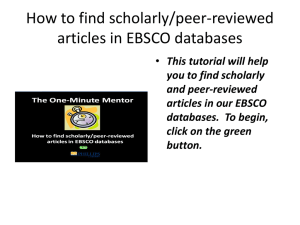

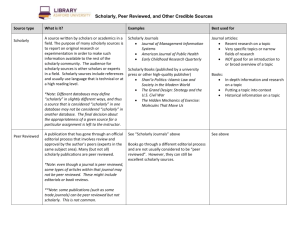

Library Resources Research Methods for Property Students – Handout By david.litting@uts.edu.au / 95143390 Library Website url: www.lib.uts.edu.au Information Resources for you to consider: The Catalogue: Is a searchable list of all the things that UTS library owns or subscribes to. It’s useful for finding the location of books, dvd’s and for finding specific journals titles. To do a ‘keyword’ search in the library catalogue use the box labelled Search catalogue on the library homepage. For other search options press ‘search’. Databases: Databases are search engines that find journal articles. We need databases because the catalogue cannot find journal articles if you type words into the catalogue. There are lists of databases that are relevant to Built Environment topics you can access by clicking on the ‘ find databases’ tab above the search catalogue box (see previous graphic). There are also specialised lists for Planning and Property Development found on this page. You can also access more information resources for Built Environment topics through the Study Guides. The navigation trail to the study guides for the Built Environment is shown below: home – students – study guides etc.. Suggested Database: ScienceDirect Science Direct is a great resource for journal articles. Despite its name it’s good for business topics and planning. It’s also a ‘full text’ database which means everything you find you can read the article straight away. Suggested Databases: Google Scholar There are other databases that are pertinent to Built Environment students, like Academic Search Premier and Wiley Interscience. However an alternative to trying these sources is to combine several UTS databases and search them via the Google Scholar interface. If you are off campus you’ll need to provide look up Google Scholar from the find databases page and click the link provided – this will connect everything you can find in Google Scholar to everything that UTS library owns. Once Google Scholar is configured you should see ‘Full Text @ UTS’ icon next to anything UTS subscribes to (see below): Suggested Database: Informit Complete (Australian content) Informit is an Australian database. It has many sub-databases. You can select them individually from a list or select them all. Whilst not containing as much information as ScienceDirect and Google Scholar, it is a useful resource to be aware of. If you come across an article in a database that does not provide the full text for you try the icon to conduct a search for the full text article elsewhere Symbols for Database Searching: An asterisk (*) – can be used to finish a word in a variety of ways. Eg: cultur* = culture, cultures, cultural, etc. Does not work in Google Scholar though. Quotation Marks (“ ..”) – can be used to search for a phrase Eg; “global warming” searches for these words next to eachother Specialist Services Links to other services – such as AUSTATS - The Australian Bureau of Statistics The Building Code of Australia online Standards Australia, Rp Data/Domain Property Data Can be found typing their names into the catalogue, or from the study guides or find databases pages. Be aware Domain covers only the city cbd and city east, whereas RP Data covers all of Sydney This is a database that features sales and rental information for properties in the inner city (the rest of Sydney is not included in our package) Logging into both RP Data and Domain Property Data requires you to provide extra logon information, which is provided after you enter your UTS username and password: Referencing Guides to the Harvard UTS System can be found via the referencing and writing guide on the left of the library homepage: Within this guide is also instructions on how to access and use referencing software. For more information about referencing software please contact myself or use the ask-alibrarian function also seen in the screenshot below. Evaluating Information: Handout The Basics – It helps to know what type of research you are doing before you begin to assemble your information. Some tasks require more ‘formal’ sources of knowledge than others. Blogs and the like are rarely used as references in peer reviewed journals for instance. The higher the level of the work you intend to do, the higher the level of work it should be based upon. The underpinning question of evaluating information is ‘who wrote this, and for whom, and why? And what sort of quality control is this writing subject to?’. One way in which quality and accuracy is assured in the publishing field, both in print and online, is via ‘editorial’ processes. Let’s take a look at some different information mediums and see what kind of editorial controls they are subject to: Blogs and personal websites are generally not edited, as they are wholly owned and controlled by their authors. Determining who publishes a websites can determine whether it is someone’s personal opinion or not. This information can usually be found at the foot of a website’s home page or in the ‘about’ area within a webpage. Websites like Wikipedia are edited by other Wikipedia contributors, thus providing more quality control. However temporary errors or distortions are still common. Notes on a Wikipedia page often point out problems with an entry – saying things like weasel words, or assertions not supported, etc. Corporate websites are better in terms of quality control like fact checking, but contain bias and advertorial content. This bias needs to be taken into account when referring to their statements and claims. Most Government and educational, also some organizational websites (.gov, .edu and .org) tend to have the most quality control, and the least vested corporate or personal interests. However there can be exceptions to these rules. Newspapers have editors and fact checking, although because of the speed at which they are published they are more likely to make errors than other print publications. However they are obliged to print corrections and provide apologies if necessary when they do this, usually very soon after the mistake was made. Books also have publishing houses to fact check them before publishing. Because of the time taken to write, market and publish a book, the amount of time to correct errors is longer. Books selected by academic libraries are often sought from academic (ie: university press) publishers and hopefully have an extra layer of quality assurance. Periodicals have different layers of editorial and quality control. They range from the lower end (popular magazines) up to trade publications and then finally scholarly or peer reviewed journals. Peer reviewed journal articles are considered to be good research because a panel of experts in the area read the article and provide suggestions and corrections before they are published. Authors: Understanding authors and their qualifications is also important. Like edited publications, professional qualifications lend weight to the opinions of writers. Writing for organizational bodies like the World Health Organization or for Government publications also implies authority for authors. Sometimes a link will be provided in a website called ‘about’ that will provide information about their background. Academic qualifications like PHD’s or job titles such as Professor confer authority. Websites – How to Evaluate Cardiff has an ‘Evaluating information in websites’ flow chart that is quite useful https://ilrb.cf.ac.uk/evalinfo/evalinfo.html The flow chart deals with a series of questions you ask yourself as you approach a resource Is the Author indicated? Is the page hosted by an organization? – If you can’t see an author, or if the information isn’t hosted by an organization you are on shaky ground! What type of website is this? What is the suffix of the url? .edu? .org? .gov .com? - .edu and .gov sites tend to be the most authoritative, then .org, then .com – as a rough general rule. Advocacy and Bias: Other websites provide useful information about a topic but do so in the cause of advocacy. Example: http://www.no-smoke.org/getthefacts.php?dp=d18 Knowing a little about the potential political value of your topic will help you determine how much advocacy will be involved when you search for information – for example the global warming debate or the Israel/Palestine debate. Check the sources these advocates use, and try to provide balance from different points of view if you can find them. Recognition: One way of determining the recognition given to a particular site is to do some research on who is linking or citing the webpage you are looking at. You can locate similar sites that "link" to a particular URL using Google. In the search box, type: link:[URL of known site] Example:link:www.deathpenaltyinfo.org Be careful to format your search exactly as shown above. It may be easier to use Google Advanced Search. Click the plus sign to open the full advanced search form, then scroll down to Page Specific Tools, and type the URL into the box labelled Find pages that link to the page. Another way of determining recognition is to look at who is bookmarking the site in question. Check to see whether a Web site has been tagged and chosen for inclusion in one of the Web-based bookmarking sites, such as del.icio.us or diigo.com. Enter the site title or the URL in the search box at the top of the page (as shown in the illustration) find out how many people have tagged this site. For blogs, tools like Technorati can assist in finding out more about blogs and bloggers. Try a search for either the blogger's name or the title of the blog, then click the Blogs tab at the top of the search results. This will show you a list of blogs that match your search. Now simply click on the title of a blog to view more information, such as the "authority" rating, number of fans, etc. (as shown in the illustration below). Technorati authority is defined as the number of blogs linking to a website in the last six months. Currency is also important - Check to see whether the website is current, or still being updated. The last update can usually be seen at the bottom of a webpage. Also, are there links to other websites? And if so do they work? Variety and balance: Finally, consult a variety of sources, not just websites. For things like Wikipedia, try and see if there are references at the end of the article, and if the references add information to the topic you are exploring look at them too. Periodicals –Magazines, Trade Publications and Scholarly Journals http://www.library.vanderbilt.edu/peabody/tutorials/scholarlyfree/ Periodicals are publications that come out every day, every week, every month, quarterly etc. The fact that they come out after a given period of time is what gives them their names. Different periodicals are for different audiences, and the information within some is considered more reliable and authoritative than in others. Magazine is a word associated with popular periodicals. Magazines tend to be easily identified in their print form because of their eye catching covers (Rolling Stone or Vogue for example) whereas Scholarly Journals tend to be a bit more low key, even plain, featuring only a masthead logo and text. Popular Magazine – Rolling Stone Scholarly Journal – Journal of Molecular Biology Similarly magazines tend to have a fairly large amount of advertising content, whereas scholarly journals do not. If you see a periodical in a newsagent the chances are it’s a popular magazine, even if it does have references, like the Harvard Business Review or the Scientific American. Scholarly journals are usually sold direct to the purchaser on subscription. Newspapers are housed within the popular/magazine bracket. Trade Publications: Between popular magazine and scholarly journals lie trade publications, for industry professionals who are not doing research or teaching at university. They are written by professionals in the industries, and sometimes journalists. It is common for these publications to be subject to the sort of scrutiny a newspaper or popular magazine might be, with editorial control, but not peer review. Ways to spot Scholarly Journals - Authors credentials listed at the top of the article, or an author biography provided to show their authority on their subject of choice - An abstract, or summary of the article - Quoting, and a bibliography or reference list at the end of an article also indicates a scholarly type of publication, though this does not guarantee peer review Although there are exceptions, popular articles tend to be shorter than scholarly articles, and use less ‘jargon’ or terminology. Is this this scholarly journal peer reviwed/scholarly? To determine if a scholarly journal is ‘peer reviewed’ scholarly journal, use these methods: Some databases like EBSCO (Academic Search Premier, Business Source Premier, and more) and Proquest have a ‘restrict to peer review’ option. Other databases purport to have only peer reviewed material, like Scopus and ScienceDirect. Another way of investigating a journal is to look up its title in the UTS library catalogue. When you do this, you should be take to the title page of the journal in the database you connect to. Information such whether its peer reviewed should be displayed on this page. Harvard Business Review – Not Scholarly (see below) If you really can’t determine whether a journal is peer reviewed any other way try looking up the journal in google. Their home page should indicate whether the journal is peer reviewed or not.. Finally - When in doubt – ask! Ask a librarian in person or online, or run a question by your lecturer. We’re all here to help. http://www.lib.uts.edu.au/students/need-help