Societies flourish when all voices are heard, when all

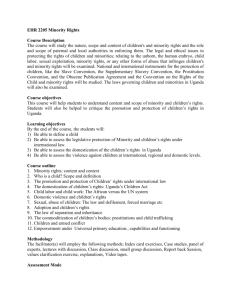

advertisement