Highlights from Hugo

advertisement

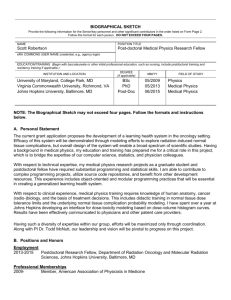

HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Karen Stapleton’s review of Hugo The film Hugo is a wonderful adaptation of Brian Selznick's novel, The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Filmed in 3D it brings to life the images in the text as much as the written narrative. The film follows the book faithfully with only a few minor changes or omissions. The opening sequence with its innovative cinematography sets the scene for the mystery and enchantment of the story. Set in 1931 in Paris most of the action takes place in the Gare Montparnasse railway station where Hugo, recently orphaned, lives on his own in its walls and keeps the clocks working. His daily routine is one of survival and we see him pilfering food and other essentials as he observes through the clock faces and other apertures the microcosm of the world that is represented in the hustle and bustle of daily life in the railway station. But the key to the story revolves around an automaton that he is trying to fix that he believes holds a message from his dead father; through his efforts he befriends Isabelle, a young girl looking for adventure. Their friendship, and Isabelle’s key that brings the automaton to life, lead to the discovery that her godfather is the famous filmmaker, Georges Méliès. It is here that the film gains momentum and a shift in focus as the audience is given insights into the art of making films and details of cinematic history. The beauty and cinematic design of these scenes makes them worthy of close study as do other sequences in the film such as Hugo’s nightmare which recreates the famous 1895 train derailment at Gare Montparnasse. Beyond the stunning visuals and 3D effects there are so many elements to this film that engage the audience and create a wonderful cinematic experience that any class would enjoy, and benefit from, studying it. The film received enormously positive reviews, with many critics praising the visuals, acting and direction. Some critics called it the best 3D visual event of the decade. At the Academy Awards Hugo received 11 nominations and won five Oscars—for Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, Best Visual Effects, Best Sound Mixing, and Best Sound Editing. Hugo also won two BAFTAs and was nominated for three Golden Globe Awards, earning Martin Scorsese his third Golden Globe Award for Best Director. Wikipedia plot summary: (downloaded 7th May, 2012) In 1931, Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), a 12-year-old boy, lives with his widowed father (Jude Law), a master clockmaker in Paris. Hugo's father takes him to see films and his father particularly loves the films of Georges Méliès. Hugo's father dies in a museum fire, and Hugo is taken away by his uncle (Ray Winstone), an alcoholic watchmaker who is responsible for maintaining the clocks in the railway station Gare Montparnasse. His uncle teaches him to take care of the clocks and then disappears. He is later discovered to have drowned. Hugo lives between the walls of the station, maintaining the clocks, stealing food and working on his father's most ambitious project: repairing a broken automaton, a mechanical man who is supposed to write with a pen. Convinced the automaton contains a message from his father, Hugo goes to desperate lengths to fix it. He steals mechanical parts to repair the automaton, but he is caught by a toy store owner, Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley), who takes Hugo's notebook from him, with notes and drawings for fixing the automaton. To recover the notebook, Hugo follows the shopkeeper to his house and meets Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), an orphan close to his age and Georges' goddaughter. She promises to help. The next day, Georges gives some ashes to Hugo, referring to them as the notebook's remains, but Isabelle informs him that the notebook was not burned. Finally he © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 1 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO agrees that Hugo may earn the notebook back by working for him until he pays for all the things he stole from the shop. Hugo works in the toy shop, and in his time off manages to fix the automaton, but it is still missing one part—a heart–shaped key. A Georges Méliès drawing similar to the one drawn by the automaton in the film. Hugo introduces Isabelle to the movies, which her godfather has never let her see, while she introduces Hugo to a bookstore whose owner (Christopher Lee) initially mistrusts Hugo. Isabelle turns out to have the key to the automaton. When they use the key to activate the automaton, it produces a drawing of a film scene, signed by Georges Méliès. Hugo remembers it is the film his father always talked about as the first film he ever saw (Voyage to the Moon) and Isabelle recognises the signature as being the name of her godfather, Papa Georges and the two of them take it to her home for an explanation. Hugo shows Georges' wife Mama Jeanne (Helen McCrory) the drawing made by the automaton, but she will not tell them anything and makes them hide in a room when Georges comes home. While hiding, Isabelle and Hugo find a secret cabinet and accidentally release pictures and screen boards of Georges' creations - the noise attracts Georges, who is deeply upset and throws Hugo out, feeling betrayed. The bookseller refers Hugo and Isabelle to a book on the history of film and are surprised that the author, Rene Tabard (Michael Stuhlbarg), refers to Méliès as having died in World War I. Tabard himself appears, and the children tell him that Méliès is alive. Tabard, a devotee of Méliès' films, owns a copy of Voyage to the Moon, thought to be the last copy of one of Méliès' films in existence. Then Hugo convinces Tabard to go to Georges' home. That night Hugo dreams of being run over by a train when trying to retrieve the heart key from the rails, a sequence that ends in a re-creation of the Montparnasse train accident. When he wakes up, he hears a loud ticking sound and discovers it is coming from his own chest, at which point he suddenly turns into the same form and shape as the automaton, but then awakens for good. Hugo, Isabelle and Tabard go to Georges' home, and at first Jeanne tells them to go before her husband wakes. However, Jeanne accepts their offer to show Voyage to the Moon when Tabard compliments her as the beautiful actress in Georges' films. As they finish watching the film, Georges appears and explains how he came to make movies, invented the special effects, and how he lost faith in films when World War I began, being forced to sell his films as chemicals to get money, and opening the toy shop to survive. He also believes the automaton he created was lost in the museum fire and nothing remains of his life's work. Hugo goes back to the station to get the automaton, to surprise Georges, but he is cornered by the station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) and his dog. Hugo escapes and runs to the top of the clock tower and hides by climbing out onto the hands of the clock. Once the inspector is gone, he runs for the exit with the automaton, but he is trapped by the inspector © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 2 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO and the automaton is thrown onto the railway tracks. Climbing onto the tracks, Hugo is almost run over by an approaching train when the officer saves him and detains him as an orphan without a guardian. While Hugo pleads with the officer, Georges arrives and says Hugo is in his care. The officer lets him go. At the end of the movie, Georges introduces a tribute ceremony to his movies with Tabard announcing that over 80 films have been recovered and restored. Georges thanks Hugo for his actions and invites the audience to "follow his dreams". Wikipedia: (downloaded 7th May, 2012) Georges Méliès (8 December 1861 – 21 January 1938), full name Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès, was a French illusionist and filmmaker famous for leading many technical and narrative developments in the earliest days of cinema. Méliès, a prolific innovator in the use of special effects, accidentally discovered the substitution stop trick in 1896, and was one of the first filmmakers to use multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, dissolves, and hand-painted color in his work. Because of his ability to seemingly manipulate and transform reality through cinematography, Méliès is sometimes referred to as the first "Cinemagician". Two of his most well-known films are A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904). Both stories involve strange, surreal voyages, somewhat in the style of Jules Verne, and are considered among the most important early science fiction films, though their approach is closer to fantasy. Méliès was also an early pioneer of horror cinema, which can be traced back to his Le Manoir du diable (1896). Stage magic: . . . While in London, he began to visit the Egyptian Hall, run by the famous London illusionist John Nevil Maskelyne, and he developed a lifelong passion for stage magic. . . Upon his return from London he worked in his father’s shoe but continued to cultivate his interest in stage magic, attending performances at the Théâtre RobertHoudin, which had been founded by the famous magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin. He also began taking magic lessons from Emile Voisin, who gave him the opportunity to perform his first public shows, at the Cabinet Fantastique of the Grévin Wax Museum and, later, at the Galerie Vivienne. In 1888 Méliès's father retired, and Georges Méliès sold his share of the family shoe business to his two brothers. With the money from the sale and from his wife's dowry, he purchased the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. Although the theatre was "superb" and equipped with lights, levers, trapdoors, and several automatons, many of the available illusions and tricks were out of date, and attendance to the theatre was low even after Méliès' initial renovations. Over the next nine years, Méliès personally created over 30 new illusions that brought more comedy and melodramatic pageantry to performances, much like those Méliès had seen in London, and attendance greatly improved. Film career: Méliès began shooting his first films in May 1896, and screening them at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin by that August. At the end of 1896 he and Reulos founded the Star- © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 3 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Film Company, with Lucien Korsten acting as his primary camera operator. Many of his earliest films were copies and remakes of the Lumière brothers films, made to compete with the 2000 daily customers of the Grand Café. This included his first film Playing Cards, which is similar to an early Lumière film. However, many of his other early films reflected Méliès's knack for theatricality and spectacle, such as A Terrible Night, in which a hotel guest is attacked by a giant bedbug. But more importantly, the Lumière brothers had dispatched camera operators across the world to document it as ethnographic documentarians, intending their invention to be highly important in scientific and historical study. Méliès's StarFilm Company, on the other hand, was geared more towards the "fairground clientele" who wanted his specific brand of magic and illusion: art. In these earliest films, Méliès began to experiment with (and often invent) special effects that were unique to filmmaking. This began, according to Méliès's memoirs, by accident when his camera jammed in the middle of a take and "a Madeleine-Bastille bus changed into a hearse and women changed into men. The substitution trick, called the stop-trick*, had been discovered.” This same stop-trick effect had already been used by Thomas Edison when depicting a decapitation in The Execution of Mary Stuart; however, Méliès's film effects and unique style of film magic are his own. He first used these effects in The Vanishing Lady, in which the by then cliché magic trick of a person vanishing from the stage by means of a trap door is enhanced by the person turning into a skeleton until finally reappearing on the stage. In September 1896, Méliès began to build a film studio on his property in Montreuil, just outside of Paris. The main stage building was made entirely of glass walls and ceilings so as to allow in sunlight for film exposure and its dimensions were identical to the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. The property also included a shed for dressing rooms and a hangar for set construction. Because colors would often photograph in unexpected ways on black and white film, all sets, costumes and actors' makeup were colored in different tones of gray. Méliès described the studio as "the union of the photography workshop (in its gigantic proportions) and the theatre stage." Actors performed in front of a painted set as inspired by the conventions of magic and musical theater. Later life: After being driven out of business, Méliès disappeared from public life. By the mid-1920s he was making a meager living as a candy and toy salesman at the Montparnasse station in Paris, with the assistance of funds collected by other filmmakers. In 1925 he married his longtime mistress Jeanne d'Alcy, and they lived together in Paris with Méliès's young granddaughter Madeleine Malthête-Méliès. By the late 1920s several journalists began to research Méliès and his life's work, creating new interest in him. As his prestige began to grow in the film world, he was given more recognition and in December 1929 a gala retrospective of his work was held at the Salle Pleyel. In his memoirs, Méliès said that at the event "he experienced one of the most brilliant moments of his life." *Stop trick – discuss how this could be considered as a precursor to stop-motion (also known as stop frame), an animation technique to make a physically manipulated object appear to move on its own. The object is moved in small increments between individually photographed frames, creating the illusion of movement when the series of frames is played as a continuous sequence. Dolls with movable joints or clay figures are often used in stop motion for their ease of repositioning. Stop motion animation using clay is called clay animation or "clay mation". © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 4 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Wikipedia: (downloaded 7th May, 2012) A Trip to the Moon or Voyage to the Moon (French: Le Voyage dans la lune) is a 1902 French black-and-white silent science fiction film. It is based loosely on two popular novels of the time: Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon and H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon. The film was written and directed by Georges Méliès, assisted by his brother Gaston. The film runs 14 minutes if projected at 16 frames per second, which was the standard frame rate at the time the film was produced. It was extremely popular at the time of its release, and is the bestknown of the hundreds of fantasy films made by Méliès. A Trip to the Moon is the first known science fiction film, and uses innovative animation and special effects, including the wellknown image of the spaceship landing in the Moon's eye. Lost ending The ending sequence of the parade and statue was considered lost until 2002, when a well preserved complete print was discovered at a barn in France. The extended version was screened at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in 2003. Hand-colored version Like many of Méliès's films, A Trip to the Moon was sold in both black-and-white and handcolored versions. A hand-colored print, the only one known to survive, was rediscovered in 1993 by the Filmoteca de Catalunya. [A film archive in Catalunya, Spain.] It was in a state of almost total decomposition, but a frame-by-frame restoration was launched in 1999 and completed in 2010 at the Technicolor Lab of Los Angeles - and after West Wing Digital Studios matched the original hand tinting by colorizing the damaged areas of the newly restored black and white. The restored version finally premiered on May 11, 2011, eighteen years after its discovery and 109 years after its original release, at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, with a new soundtrack by the French band Air. It was released by Flicker Alley as a 2-disc Blu-Ray/DVD edition, also including the documentary The Extraordinary Voyage about its restoration on April 10, 2012. Amazon search results 7 May, 2012: A Trip to the Moon Restored (Limited Edition, Steelbook) [Blu-ray] Starring George Melies (2012) (13 customer reviews) Blu-ray Buy new : $39.95 $29.96 3 new from $29.41 1 used from $29.95 © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 5 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Wikipedia: 1895 train derailment (downloaded 7th May, 2012) The original photo of the Granville– Paris Express wreck on 22 October 1895. The original Gare de l'Ouest name of the station is visible on the outside of the building. The Gare Montparnasse became famous for a derailment on 22 October 1895 of the Granville–Paris Express that overran the buffer stop. The engine careened across almost 30 metres (100 ft) of the station concourse, crashed through a 60-centimetre (2 ft) thick wall, shot across a terrace and smashed out of the station, plummeting onto the Place de Rennes 10 metres (33 ft) below, where it stood on its nose. Two of the 131 passengers sustained injuries, along with the fireman and two conductors. The only fatality was a woman on the street below who was killed by falling masonry. The accident was caused by a faulty Westinghouse brake and the engine drivers who were trying to make up for lost time. A conductor was given a 25-franc fine and the engine driver a 50-franc fine. The story of the train crash and the picture features in the 2007 children's novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick and in its film adaptation, Hugo, where it was in one of Hugo's nightmares. See following text from pages 380-381 of Brian Selznick’s novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret (and see pp382-383 for double page archival photo – as above) At last it was the night before the visit from Etienne and René Tabard. Hugo could hardly fall asleep, and when he did, he dreamed about a terrible accident that occurred in the train station thirty-six years ago, which people still talked about. Hugo had heard stories about the accident from the time he was very young. A train had come into the station too fast. The brakes had failed, and the train slammed through the guardrail, jumped off the tracks, barrelled across the floor of the station, rammed through two walls, and flew out the window, shattering the glass into a billion pieces. © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 6 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Wikipedia: Automaton (downloaded 7th May, 2012) An automaton (plural: automata or automatons) is a self-operating machine. The word is sometimes used to describe a robot, more specifically an autonomous robot. Etymology: The word automaton is the latinization of the Greek αὐτόματον, automaton, (neuter) "acting of one’s own will". It is more often used to describe non-electronic moving machines, especially those that have been made to resemble human or animal actions, such as the jacks on old public striking clocks, or the cuckoo and any other animated figures on a cuckoo clock. Modern automata: The famous magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805–1871) was known for creating automata for his stage shows. The period 1860 to 1910 is known as "The Golden Age of Automata". During this period many small family based companies of Automata makers thrived in Paris. From their workshops they exported thousands of clockwork automata and mechanical singing birds around the world. It is these French automata that are collected today, although now rare and expensive they attract collectors worldwide. The main French makers were Vichy, Roullet & Decamps, Lambert, Phalibois, Renou and Bontems. Automaton in the Swiss CIMA museum (Centre International de la Mécanique d'Art) Hugo and his father work on the automaton. The automaton in the film prepares to write. © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 7 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO HUGO – THE FILM - Focuses for study The Past Time Historical events History of cinema Clocks Highlights from HUGO Mechanics & inventions Connections Magic & illusion Adventures & dreams Automaton Keys and locks Secrets and mysteries Family Home Friendships Self/identity AND? © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 8 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO For example, How represented in the film? For what meaning/purpose? Symbols of clocks and watches Hugo viewing the world ‘through’ time as it ‘literally’ ticks by him Hugo hanging off the clock arm to escape from the Station Inspector; suspended ‘in time’ (as his life is?) Georges Méliès as a recluse from his past glory; his initial reference to ‘ghosts’ when he sees the notebook and sketches of his automaton Iconography and intertextuality – train crash and archival image manifested in Hugo’s nightmare Flashbacks of Hugo with his father and his father’s death (as part of the exposition) And . . .? Students experiment with their own imaginative writing that is set in a particular historical time and place/context is set in a limited ‘space’ (like a railway station) explores an aspect of time as a key layer to the narrative uses a sustained metaphor or motif/symbol incorporates flashbacks to provide exposition uses intertextual references to real events and/or iconic images incorporates visuals as part of its narrative And . . .? © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 9 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Film features See official film website: http://www.hugomovie.com.au/#home for trailers(videos), story “Hugo is the astonishing adventure of a wily and resourceful boy whose quest to unlock a secret left to him by his father will transform Hugo and all those around him, and reveal a safe and loving place he can call home.” images gallery downloads – images and wallpapers tagline – Unlock the secret Setting and context – 1931 Paris and its streets, Montparnasse railway station. Mise-en-scene and other effects used to establish railway station, Paris streets/environs and the distinctly French culture. Note the significance of iconography and the historical and cultural referencing in the film created through both the audio and visual elements. Intertextuality: Georges Méliès and his filmmaking and innovative special effects; classic books; silent films, studios and actors; train crash at Montparnasse station Minor characters in railway station – their lives and stories; role in film? The microcosm of the world that is represented in the hustle and bustle of daily life in the railway station. To what extent are they stereotypes or individually drawn characters? The railway station Book seller, Monsieur Labisse Café owner, her dog and ‘admirer’ Monsieur Frick Flower seller The policeman (with wife problems!) Hugo’s family and friends Hugo’s father Hugo’s uncle Claude The film researcher, Rene Tabard George’s wife and former actress, Mama Jeanne And? The main characters Hugo Isabelle George Méliès Station Inspector (is he a serious character, a caricature or part both or. . .?) The automaton (as a silent character?) And? © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 10 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Cinematography Mise-en-scene of railway station and Paris streets; a microcosm world Camera angles and shots; points of view/perspective, frame composition Pace/rhythm of shots/ pixilation and slow motion 3D and use of special effects Sound – diegetic/non-diegetic. Example of key scenes for discussion and analysis Opening credits and opening sequence/establishing shots Cityscape, winter and snow, entering station, zooming through, clock and Hugo’s face peering out, world ‘inside’ station, inside the clock, Hugo winding clock, film title on screen. Compare the film’s opening to the novel’s opening: A Brief Introduction THE STORY I AM ABOUT TO SHARE with you takes place in 1931, under the roofs of Paris. Here you will meet a boy named Hugo Cabret, who once, long ago, discovered a mysterious drawing that changed his life forever. But before you turn the page, I want you to picture yourself sitting in the darkness, like the beginning of a movie. On screen, the sun will soon rise, and you will find yourself zooming toward a train station in the middle of the city. You will rush through the doors into a crowded lobby. You will eventually spot a boy amid the crowd, and he will start to move through the station. Follow him, because this is Hugo Cabret. His head is full of secrets, and he’s waiting for his story to begin. Professor H. Alcofrisbas Consider: a) The use of non-diegetic and diegetic sound: “steam train” sound overlays credits and acts as audio J-cut to opening shots. b) Camera angles and shots: Whose point of view are we given? Why? How is it established? What is Hugo’s view of, and attitude, to his world? How is this shown? What is the significance of the representation of Hugo’s role as observer behind the walls and station clock? What is the effect of the pixilation shot*/quick frame rate that quickens the pace of the film and POV, ie the zooming and movement in this sequence? * Pixilation shot is a fast moving point of view (POV) produced by the camera using individual images/single frames in a burst of several per second. c) What is the effect of there being no dialogue in the opening sequence? d) How does this opening sequence serve as an establishing shot for the whole film? What elements are emphasised? What is the viewer’s response? © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 11 HIGHLIGHTS FROM HUGO Some other useful scenes for close analysis: Narrative/ plot Cinema history & commentary • Hugo’s flashback of father • Research at the library • Georges and Hugo in shop together • The glass studio visit • Mama Jeanne viewing film • The automaton (“What is that?”) • Georges Méliès’ talking about his life and work • Hugo’s anger and loss; automaton’s final drawing • ‘Stop trick’ filming • Hugo’s nightmare • The gala tribute to Georges Méliès • Escaping the station inspector • Automaton falls on train lines See also a selection of still frames for examination of mise-en-scene, composition and camera angles © Presented by Karen Stapleton, AIS Page 12