Executive Summary

advertisement

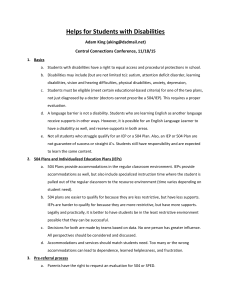

Executive Summary Disable the Label – Improving Post-Secondary Policy, Practice and Academic Culture for Students with Disabilities In the past several decades, Nova Scotia has made great strides toward enabling persons with disabilities to access post-secondary education (PSE). Nevertheless, persons with disabilities remain among the most undereducated and underemployed groups in Nova Scotia, and in Canada. Ensuring persons with disabilities have access to adequate support during PSE is fundamental if we want this to change. Disable the Label: Improving Post-Secondary Policy, Practice and Academic Culture for Students with Disabilities provides an in-depth discussion of the challenges and supports for persons with disabilities found within the PSE system. In turn, it begins to re-conceptualize how disability should viewed and accommodated within an academic environment, and provides a roadmap for immediate and long-term improvement. STUDY DESCRIPTION AND KEY RESEARCH FINDINGS In this study, we focused our attention on three interrelated areas of inquiry. We: 1. Examined how ‘disability’ may be defined and contextualized in contemporary Canadian society, and discussed how our orientation toward ‘disability’ impacts learning and educational environments. 2. Critically explored the existing PSE support systems for students with disabilities provided by the Federal/Provincial governments and institutions. 3. Identified numerous barriers faced by students with disabilities within the postsecondary system, including those found in the classroom, in institutional and government policy, and within the Student Financial Assistance programs. EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT CHALLENGES The Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) by Statistics Canada found that 20.8% of Canadian 18-21 year olds reported having a disability (Statistics Canada, 2013). Yet registered students with disabilities made up fewer than 6% of the province’s university population, and about 11% of the Nova Scotia Community College’s (NSCC) population in the 2012/13 school year. Even when accounting for the fact that some youth may be too severely disabled to attend PSE, it is clear that youth with disabilities are simply not entering PSE at the same rate as their peers. Accordingly, national level research has shown that persons with disabilities are significantly less likely to graduate from college, university, or graduate school in comparison to the general population (HRSDC, 2009). In terms of employment, a greater proportion of youth with disabilities hold multiple jobs in a year, have jobs unrelated to their credentials, are neither working nor attending school, and/or live in low income households (Hughes & Avoke, 2010; Prince, 2014). This means that youth with disabilities are more likely than non-impaired youth to be un- or underemployed, and to be in poverty. As nearly 75% of new jobs in Canada require PSE as a condition of employment (AUCC, 2011), increasing the number of persons with disabilities obtaining this credential will drastically increase this population’s ability to take part in the workforce, increasing their self-efficacy and involvement in the community, and reducing their poverty rates. Attending PSE is more costly for persons with disabilities. They face greater expenses, longer study periods and lower in-study employment earnings. In addition to the elevated costs facing PSE students in general, students with disabilities must often pay for assistive devices, tutors and medical supports. Moreover, students with disabilities often take reduced course loads to allow them to manage their disability, which increases the time their program takes to complete and, consequently, the cost (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, 2009). The demands of balancing their responsibilities and education makes students with disabilities also less likely to be able to work during their academic career, significantly reducing their revenues. They face significantly greater challenges finding co-op placements or volunteer opportunities within their field (including on campus) that are accessible and willing to train them to complete their education (Annabelle et al, 2003; Fredeen et al., 2013; Personal Communication, 2013; 2014). This combination of factors leads students with disabilities to accumulate greater debts (Standing Senate Committees on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 2011; PSDS, 2013). Higher debts compounded with lower long-term employment earnings mean that PSE costs can place students with disabilities in financial hardship for a greater amount of time than their non-disabled peers (CMSF, 2009). Of course, financial problems are only one factor effecting youth with disabilities’ representation in PSE. Increasing youth with disabilities’ ability and desire to attend PSE is equally, if not more, important. Students with impairments face barriers within the academic system itself that threaten to impede their ability to excel in PSE, as well as impact the quality of their college/university experience. These barriers include systemic issues such as resource shortages, lengthened timelines to graduation, inaccessible classrooms, the dependence on the written word in educational communication, and more. Perhaps more concerning are the cultural barriers persons with disabilities face: having a disability continues to be heavily stigmatized and often serves to make students feel isolated and discriminated against by both peers and staff, undermining their educational experience and ability to learn (Harrison, 2012; Goode 2007; Mullins,& Preyde, 2013; Vickerman & Blundell, 2010). We must actively and diligently work to improve academic culture for students with disabilities. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Throughout time, the term ‘disability’ has been applied in many ways. Today, there are two main schools of thought about disability: the medical model, and the social model. The medical model interprets the illness or impairment as the disability. Thus, disability is seen to be fixed within an individual (HRDC, 2003). In contrast, the social model frames the concept of disability in terms of the cultural, socioeconomic, and political disadvantages that result from an individual’s exclusion (HRDC, 2003). Since ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Canada has shown a commitment to the social model. Within this model, the terms, “impairment” and “disability” have very precise meanings. “Impairment” refers to problems in physical or mental functioning such as significant loss (e.g. the loss of a limb) or deviation (e.g. legs that cannot support ones weight) from the norm (WHO, 2002), whereas a “disability” refers to the interaction between individuals with a health condition and personal or environmental factors (WHO, 2002). Importantly, this shifts the onus of ‘disability’ onto our culture and societal structures as opposed to the individual; we have the capacity to influence the experience of disability. Within this report we underscore the need to implement the social model of disability on post-secondary campuses, most notably through the utilization of the Universal Design and Universal Design for Learning frameworks. The sentiment behind this idea is that if we create environments that are accessible to everyone, no one will be disadvantaged relative to their peers. Creating truly accessible environments is a lofty goal, however it is an ideal our culture has begun to embrace and must progress towards. The PSE environment has a duty, obligation, and underlying commitment to ensure that all people have the ability to attend and excel. However, we recognize that the adoption of a Universal Design framework involves significant changes to our educational system, and that we must also work within the confines of our current situation. At this point in time, examining how academic accommodations are viewed, handled, and received is very important. We strongly emphasize the need for formal recognition of disability accommodation as human rights legislation (known as the “Duty to Accommodate”), and for accommodation policies to be recognized as anti-discrimination policies. In short, a greater effort needs to be made to ensure that students’ right to accommodations is not seen as subjective or ‘auxiliary’ to the core of PSE. Institutionally, this is best done by formally integrating accommodations policy into broader anti-discrimination policy, and by ensuring faculty are properly educated on the subject. DISABILITY SERVICES The Canada-Nova Scotia Labour Market Agreement for Persons with Disabilities (C-NS LMAPD) directs Federal and Provincial government resources to improve the employment situation for persons with disabilities in Nova Scotia (PSDS, 2013). Recognizing the importance of PSE in advancing the employment opportunities of this demographic, a portion of this money is used to fund Post Secondary Disability Services (PSDS), a section within the Department of Labour and Advanced Education (LAE). PSDS funds on-site Disability Services Offices (DSOs) at nine Nova Scotia universities and 13 NSCC campuses. PSDS also funds direct grants for students with disabilities. DSOs are the primary mechanism PSE institutions’ use to uphold their “Duty to Accommodate”. As is outlined through funding agreements, institutional DSOs’ core responsibilities with respect to students with disabilities include (1) arranging academic accommodations and (2) connecting students with available federal and provincial funding. Improving the physical accessibility of campus and administering targeted skills development programming may also be areas of focus for DSOs. The funding received by PSDS has remained the same, and has been distributed in the same manner, since 2004. Over ten years, the number of students utilizing DSOs has more than doubled at universities, and greatly increased at the NSCC such that universities have experienced a 42.2% decrease in funding provided per registered student with a disability since 2007/08. At the same time, there has been significant demand for different services, and better student outreach, including on awareness and stigma reduction. Moreover, there has been a shift in the pervasiveness of particular impairments amongst students: while learning disorders continue to be the most common disability, the prevalence of mental health issues has steadily risen and the reports of mobility, vision, or auditory impairments have fallen.1 This has resulted in staff being overworked, possibly needing additional impairment specific training, and having insufficient resources to provide the highly individualized service they are meant to. This must be addressed. PREPERATION FOR THE WORKFORCE The express purpose of the C-NS-LMAPD, and by extension PSDS, has been to facilitate the participation of persons with disabilities in PSE and in the labour force, and specifically to bolster the number of persons with disabilities able to obtain high-level positions within their fields. PSDS funds DSOs on campus within the context of this mandate, meaning that preparing students with disabilities to enter the workforce is in fact meant to be a fundamental objective of DSOs. However, there is currently little to no programming aimed at transitioning students to work. Moreover, very little emphasis is placed on developing self-advocacy skills in students, which they will need to succeed in all areas of life, particularly within the workforce. UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING Unfortunately, many students with disabilities report feeling that faculty members lack the knowledge, willingness and/or ability to create accessible learning plans. Similarly, faculty have expressed concern (e.g. Canadian Teacher’s Foundation, 2012; DiGiorgio, 2009) that they do not feel adequately equipped to teach or advise students with disabilities, particularly those with mental health concerns and learning disorders. Compared with the P-12 system, professors at universities are hired more based on 1 As primary diagnoses. their expertise in an area of research than their teaching ability. While this allows students to learn from the best researchers in their field, it does not always ensure that instructors are able to effectively transmit their knowledge to their pupils. A basic understanding of the differences in in-class academic needs is fundamental to ensuring students with disabilities will receive the same quality of education as their peers. If information on this subject is not provided to the people expected to teach Nova Scotian students, Nova Scotia cannot expect these people to provide a quality education to differently-abled learners. PROBLEMATIC ATTITUDES OF FACULTY & STAFF While the majority of faculty and staff at PSE institutions are kind and well-intentioned individuals, they may, consciously or not, hold and purvey stigmatizing attitudes towards students with disabilities, and/or obstruct students accessing accommodations and services. The outdated notion that all students have a responsibility to mould to the classroom as opposed to the classroom moulding to them is still pervasive. At universities in particular, many staff harbour the antiquated view that PSE is meant to be elitist, and that some people simply do not belong in university; notably people who would need academic accommodations. This belief is discriminatory, judgmental and has no place in our public PSE institutions. Moreover, institutions must take ownership of the fact that the PSE system has been developed based on a ‘typical’ student, and that their will always be deviations from the norm. An additional area of concern surrounds faculty denying accommodations because “they jeopardize academic integrity”. The impact of academic accommodations on student learning has been a heavily investigated, though often controversial, topic. Although there is still a need for greater research in this area, the available evidence strongly suggests that allowing all students to access these accommodations would have little effect on the performance of students in general, whereas the removal of these supports would be of significant detriment to students with disabilities. FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS There is a significant amount of financial aid available to students with disabilities through the Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP) and Nova Scotia Student Assistance Program (NSSAP). However, there are notable gaps in funding which need to be addressed to ensure that all persons with disabilities are able to afford to go on to PSE. Foremost, both CSLP and NSSAP require a psycho-educational (psych-ed) assessment conducted after age 18 or within the past 5 years, to access financial supports as a student with a learning disorder/ADHD. As a psych-ed assessment averages about $1500, though occasionally runs as high as $3000, requiring an updated psych-ed to access supports can be extremely costly for students (OUSA, 2012). Students applying for the Grant for Services and Equipment for Students with Permanent Disabilities are eligible for reimbursement of up to 75% of the costs related to this assessment, but only if the test comes back positive, and only to a maximum of $1,200. Many students cannot afford the upfront expense, even if the reimbursement is guaranteed. In situations where the student receives the full $1,200 reimbursement, they still pay about $300 per assessment on average, with some students paying over well over $1000. This policy unfairly affects students of lower socio-economic status, who are less likely to be able to pay such a large sum upfront. Moreover, students who have reason to believe they may have LD, but who have not been previously tested may be leery of spending money on the test, given that students receiving a negative result are not reimbursed. Secondly, although Nova Scotian students may access up to $16,000 worth of grant money for goods and services (if award the maximum amount for both the Federal and Provincial grants), this still may not cover the cost of what a student needs to attend and excel in school in some cases. For example, a student requiring attendant care while on campus is essentially paying another persons salary out of these grants in addition to any technology, tutors or other help they may need. It is unlikely that it is feasible to cover all of these costs with $16,000, even if they are awarded the maximum amount of (non-disability related) SFA. This must be addressed. Most practically, PSDS could implement an appeals process similar to that of NSSAP’s, giving students the opportunity to appeal for greater funds if they do not feel they will be able to access the resources they need without further funding. Similarly, this appeals process should consider raising the maximum amount of funds given to students who must employ others in order to attend school, ensuring that they are able to fairly compensate these individuals for their time. RECOMMENDATIONS Based on our assessment of the current supports in place for students with disabilities, we make a number of recommendations aimed at PSE institutions, DSOs, LAE and the NSSAP and CSLP, under six themes: 1. CONTEXTUALIZING DISABILITY ISSUES AS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES 2. EMBRACING UNIVERSAL DESIGN AND THE SOCIAL MODEL ON POST-SECONDARY CAMPUSES 3. CHANGING THE FUNDING FORMULA FOR THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE LMAPD GIVEN MASSIVE INCREASE IN SERVICE UPTAKE 4. ENSURING A STUDENT’S DISABILITY IS NOT A FINANCIAL BARRIER TO EDUCATION 5. CREATING CAMPUS ENVIRONMENTS THAT ARE ACCEPTING OF AND KNOWLEDGABLE ABOUT DISABILITY ISSUES 6. GROWING STUDENT SELF-ADVOCACY SKILLS AND SMOOTHING THE TRANSITION FROM SCHOOL TO WORK. The underlying theme of our recommendations is equal access to PSE that does not feel like a “burden” on the student nor the institution. Equal opportunity for persons with disabilities to achieve their educational goals and reach their full potential in their chosen fields is not simply an ideal, it is a human right. We need a very different approach to the conceptualization and integration of disability at PSE institutions in Nova Scotia. We must do better, we can do better, and this report shows how.