DOCx

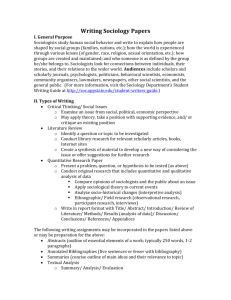

advertisement