Thomas Burton November 6, 2013 Biology Lab Wednesdays at 4pm

advertisement

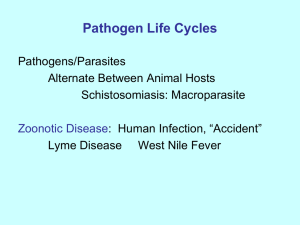

Thomas Burton Biology Lab Wednesdays at 4pm Summary November 6, 2013 “West Nile Virus Epidemics in North America Are Driven by Shifts in Mosquito Feeling Behavior.” Introduction: This study was conducted to learn more about the exposures to “West Nile Virus” which has become the continent’s leading vector-borne illness. It was first found in 1999 and has caused many large illness outbreaks. The study focuses on the primary bird-source that carry the illness called “Turdus Migratorius” or otherwise known as “The American Robin.” The mosquitos become infected while feeding on the birds. The mosquitos then feed on humans and transmit the sickness thus making the mosquitos the medium from bird to human exposure. Once the American Robins leave for migration, the mosquitos then switch their primary food source to humans. The research has 4 different hypotheses but the main focus is on the hypothesis that states “…epidemics are driven by a shift in mosquito feeding behavior from birds to mammals.” (Page 0607, paragraph 1). The objective of this test is to find out what times of the year the mosquitos most look for humans to feed on and potentially infect with WNV. With this knowledge we can better prepare ourselves against mosquito bites by using extra protection and caution during these high-exposure times. With added efforts of mosquito repellent, covering our skin, and avoiding mosquito prone areas during these times we can decrease the amount of WNV exposure. What we want to accomplish is reduce the number of outbreaks that happen every year. Material and Methods: The experiment that was used in this research was placing mosquito traps in six different locations. The locations were 3 city urban areas, 2 residential areas, a city park. Each of the areas was roughly 1 kilometer long. The type of mosquito used in this test is called “Culex Pipiens” which are the most common carriers of WNV. Over a span of 5 months, the researchers set the traps for two nights every two weeks to catch mosquitos. The traps used light and dry ice to lure the mosquitos in. The ones that were collected were cx. pipens that had recently fed and were engorged. The contents of their last meals were analyzed to determine two things. First, to determine if the mosquito’s meal came from a bird or a mammal by analyzing the DNA of the blood. Second, to determine if the meal contained the evidence of the WNV by looking for WNV RNA. The other component to the test was to track the quantity of American Robins in these 6 different areas. The quantity of birds was estimated using “fourto six-point transects, six-minute duration preformed at each site monthly.” (Page 0609, paragraph 6). During these bird observation times, the researchers found that the change in quantity of the birds were almost the same in each of the sites where the mosquito traps were set. Each month the quantity of birds was recorded in each of the sites to see when the changes in population occurred. After all the data on the cx. pipiens and the American Robins was collected it was placed into a model to try and predict when the time of year that human exposure to WNV was at its highest. Results: The tests showed that the increase of West Nile Virus exposure to humans was due to the lowered population of American Robin, which is the mosquito’s preferred target. The test showed that starting in May and June, 51% of the meals collected from the mosquitos came from the robins. After June, the population of American Robins began to decline. The decline was attributed to the migrating of the robins after mating. At the same time that the robin population started to drop, the quantity of human blood meals began to increase. With fewer robins, the probability of humans being targeted for meals went up. Results show that “the probability of mosquitos feeding on humans and mammals increased from 0.040 and 0.064 in mid-June and 0.28 and 0.39 in mid-September.” (page 0607 paragraph 2). The results show that the hypothesis isn’t wrong about the levels of West Nile Virus exposure are affected by the changes in mosquito feeding. When the population of American Robin drop after their mating season, the mosquitos become more likely to feed on humans and infect them with the West Nile Virus. This means that humans are at higher risk of exposure at the end of summer beginning of fall when the bird population drops due to migration and the mosquitos have to find another source to feed. Discussion: This was a very detailed and important study to do. As humans we are always looking for a way to avoid potentially hazardous illnesses. The results of this study have helped us understand more about how the effects of mosquito feeding habits correlate to the exposure of WNV to humans. These feeding shifts has helped us understand that “the increase over time in the probability of Cx. pipiens feeding on humans results in a greater number of human WNV infections than if the mosquitos fed on humans with the same probability as in early summer.” (page 0608, Discussion: paragraph 2.) These results support the hypothesis completely. We are at a low risk of exposure in the early summer when the robin populations are still high. The mosquitos prefer to feed on them instead of us. We start to see more risks of being fed on by mosquitos when the robins start to migrate and the mosquitos are forced to find another source of food. Unfortunately, that would be us as humans. We need to take extra precautions after June and especially in the beginning of fall when the robin population is at it’s lowest. Using this information we can protect ourselves from this nasty illness and hopefully one day make it extinct. There are too many other illnesses that we should be worrying about rather than WNV which can and should be avoided.