What is new in the context of Social Media?

advertisement

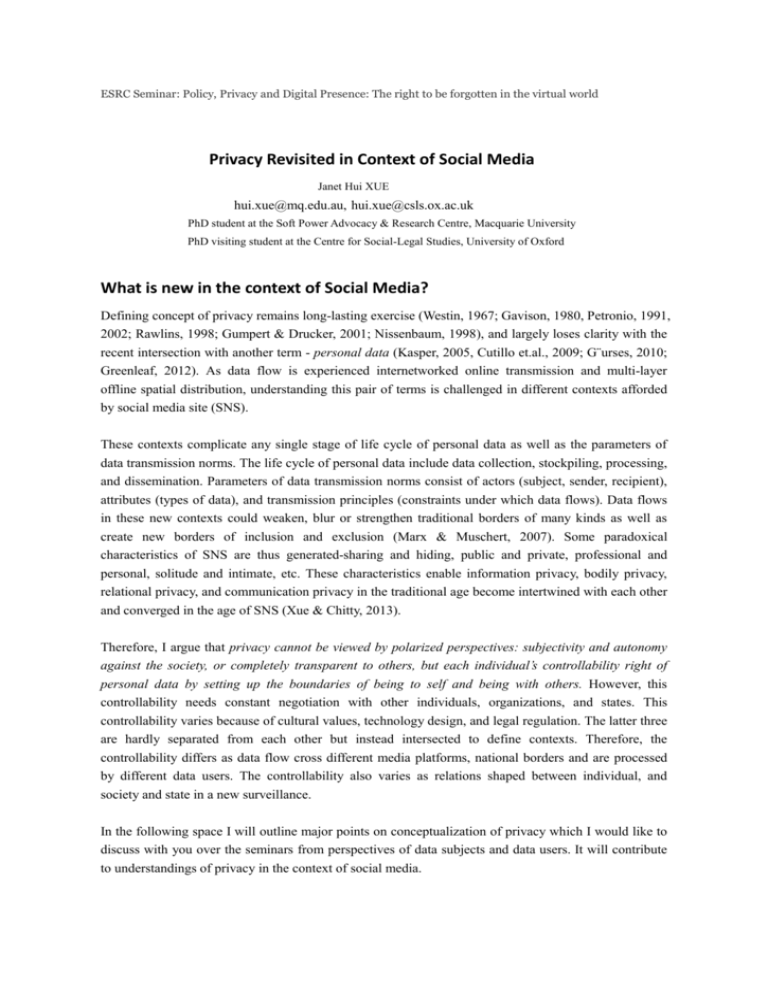

ESRC Seminar: Policy, Privacy and Digital Presence: The right to be forgotten in the virtual world Privacy Revisited in Context of Social Media Janet Hui XUE hui.xue@mq.edu.au, hui.xue@csls.ox.ac.uk PhD student at the Soft Power Advocacy & Research Centre, Macquarie University PhD visiting student at the Centre for Social-Legal Studies, University of Oxford What is new in the context of Social Media? Defining concept of privacy remains long-lasting exercise (Westin, 1967; Gavison, 1980, Petronio, 1991, 2002; Rawlins, 1998; Gumpert & Drucker, 2001; Nissenbaum, 1998), and largely loses clarity with the recent intersection with another term - personal data (Kasper, 2005, Cutillo et.al., 2009; G¨urses, 2010; Greenleaf, 2012). As data flow is experienced internetworked online transmission and multi-layer offline spatial distribution, understanding this pair of terms is challenged in different contexts afforded by social media site (SNS). These contexts complicate any single stage of life cycle of personal data as well as the parameters of data transmission norms. The life cycle of personal data include data collection, stockpiling, processing, and dissemination. Parameters of data transmission norms consist of actors (subject, sender, recipient), attributes (types of data), and transmission principles (constraints under which data flows). Data flows in these new contexts could weaken, blur or strengthen traditional borders of many kinds as well as create new borders of inclusion and exclusion (Marx & Muschert, 2007). Some paradoxical characteristics of SNS are thus generated-sharing and hiding, public and private, professional and personal, solitude and intimate, etc. These characteristics enable information privacy, bodily privacy, relational privacy, and communication privacy in the traditional age become intertwined with each other and converged in the age of SNS (Xue & Chitty, 2013). Therefore, I argue that privacy cannot be viewed by polarized perspectives: subjectivity and autonomy against the society, or completely transparent to others, but each individual’s controllability right of personal data by setting up the boundaries of being to self and being with others. However, this controllability needs constant negotiation with other individuals, organizations, and states. This controllability varies because of cultural values, technology design, and legal regulation. The latter three are hardly separated from each other but instead intersected to define contexts. Therefore, the controllability differs as data flow cross different media platforms, national borders and are processed by different data users. The controllability also varies as relations shaped between individual, and society and state in a new surveillance. In the following space I will outline major points on conceptualization of privacy which I would like to discuss with you over the seminars from perspectives of data subjects and data users. It will contribute to understandings of privacy in the context of social media. Data subjects: Sharing and hiding 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. What I would like to share or hide – classification of personal data When I would like to share or hide – retention and deletion Why I would like to share or hide – cultural value and social norms Whom I would like to share or hide – inclusion and exclusion What harms might occur to me - inequality and injustice What I can do if these harms occur to me – technical design and legal solution Data users: Collection and process (misuse) Is it personal data at all – personal data and impersonal data (anonymity, pseudo-anonymity) What are criteria for collecting Should this criteria differ to different collectors – corporation, governments, individual users Categorization of collection and misuse: over collection with notice, collection without insufficient notice, intentional/unintentional leaking, intensive data mining for marking purpose, intrusion of private space (Xue & Chitty, 2013) 5. What are economic value and social impact of privacy loss for corporation and individuals? – sharing ownership and sharing responsibility 1. 2. 3. 4. New surveillance Surveillance is an approach of population management in terms of politics, economics and culture. 1. Surveillance erodes our privacy: past, present and future 2. We use surveillance technologies to protect our privacy (Marx. 2003) 3. We monitor others while we intend to protect our own privacy 4. We are all watchers while being watched with incomparable capabilities 5. Mass surveillance leads to social sorting and differentiates people’s protection capability of privacy (Lyon, 2003) 6. Mass surveillance changes the relations between individuals, organization and society Privacy, security and identity (some discussion above also refers to this aspect) 1. Exchange privacy for security –do we feel secure when living in society of documented mobility, activity and location? 2. What happens to personal data is a deeply serious question if that data in part actually constitutes who the person is (Lyon, 2003). 3. Present different sets of personal data in different contexts – multi-identity management Reference Bennett, C.J. and Parsons, C. (2013) Privacy and surveillance: The multidisciplinary literature on the capture, use, and disclosure of personal information in cyberspace, in Dutton, W. ed., The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies. Cutillo, L.A. and Molva, R. and Strufe, T. (2009) Safebook: Feasibility of transitive cooperation for privacy on a decentralized social network, http://www.p2p.tu-darmstadt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Group_P2P/share/p2p-ws10/safebook.pdf, accessed on 2012.10.7 Gavison, R. E. (1980) ‘Privacy and the Limits of Law’, The Yale Law Journal, 89 (3):421-471. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2060957, accessed on 2012.08.30. Greenleaf, G (2012) ‘Global data privacy in a networked world’(in press) Chapter in Brown, I (Ed) Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1954296, accessed on 2012.08.30. Gumpert and Drucker (2001) ‘Public Boundaries: Privacy and Surveillance in a Technological World,’ Communication Quarterly, 49(2): 115-129. Kasper, D. V. S. (2005) The evolution (or devolution) of privacy, Sociological Forum, 20: 69-92. Lyon, D. (2003) Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk and Digital Discrimination, Routledge. Marx, G. (2003) ‘A Tack in the Shoe: Neutralizing and Resisting the New Surveillance’, Journal of Social Issues, Vol.59 (2), pp.369-390. Marx, G. and Muschert, G.W. (2007) Personal Information, Borders, and the New Surveillance Studies, http://web.mit.edu/gtmarx/www/anrev.html, accessed on 2013.8.23. Marx, G. (2012) “You paper please” : Personal and professional encounters with surveillance, in Ball, K. et.al., ed., Routeledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies. Nissenbaum, H. (1998) Protecting Privacy in an Information Age: The Problem of Privacy in Public, http://www.nyu.edu/projects/nissenbaum/papers/privacy.pdf, accessed on 2012.8.30. Petronio, S. (2002) Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. New York: State University of New York Press. Rawlins, W. K. (1998) ‘Theorizing public and private domains and practices of communication: Introductory concerns’,Communication Theory, 8 (4): 369-380. Warren, Samuel and Brandeis, Warren, 1890, The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–220. Westin, A. F. (1967) Privacy and Freedom. New York: Atheneum. Xue, H.; Chitty, N. (2013) Commercial Misuse of Personal Data by Stakeholders of SNS and Its Policy Implications: A Case Study on Weibo, presented on China and the New Internet World: The Eleventh Chinese Internet Research Conference (CIRC11), Oxford Internet Institute, Oxford, 6.15.