The role of temporary

advertisement

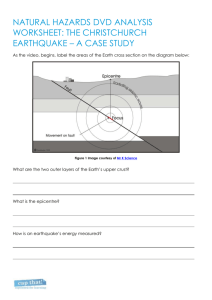

Permission to experiment, the right to fail, and the opportunity to succeed: The role of temporary use in building resilient cities Author: Suzanne Vallance Abstract: Christchurch was once well-known for being the most conservative of New Zealand cities, but was suffering long-term inner-city decline as suburban malls proliferated. Then, in 2010, an extended earthquake sequence began that resulted in the destruction and demolition of over 80 per cent of the CBD. The Christchurch City Council (CCC) was overwhelmed and new institutions emerged to manage recovery functions and activities. Despite these most challenging of circumstances, four years later, the New York Times nominated Christchurch the second best city in the world to visit in 2014, and specifically mentioned the work of two community-led, post-quake networks undertaking temporary installations on demolition sites: Greening the Rubble and Gap Filler. Both groups work with volunteers and donors (including the CCC), they have helped rejuvenate the CBD, situated the city as the country’s creative capital, and promoted a civic revival. While it has been said that temporary use is a waste of time, this paper argues instead that it is precisely because they are temporary that practitioners, policy-makers and civil society have been liberated and enabled. Temporary projects create interstitial spaces that are neither permanently real, nor wholly imagined; they thus provide and promote permission to experiment, the right to fail, and the opportunity to succeed. Because these qualities are valuable for any city, the paper concludes that although temporary use has played a key role in earthquake recovery, there are implications for urban management more generally. Introduction It is traditional to think that the appropriate weaving of policy, practice and civil society will lead to relevant and desirable outcomes such as, for example, improved public spaces, inner city revitalisation, improved security or even (given climate change and peak oil predictions) resilience. The latter has become an important construct for those concerned with the ways in which cities adapt to, or cope with, inept governance or austerity measures, industrial decline and the flight of industry, environmental devastation, or so-called natural disasters. In this paper we explore ways in which a particular form of DIY urbanism – temporary use – has helped a city recover from an extended earthquake sequence. Despite having been dismissed on more than occasion as a ‘waste of time’, we focus on the role of temporary use projects and organisations in promoting a more civil society, activating policy-makers, and enabling communities. We document how temporary projects create spaces that are neither permanently real, nor wholly imagined and show how these interstitial spaces provide permission to experiment, the right to fail, and the opportunity to succeed. This, we argue, is not despite but because they are temporary. Consequently, the paper concludes that although we have explored temporary use in the context of earthquake recovery, there are implications for urban ‘crisis’ management and resilience more generally. Temporary use and DIY urbanism Those interested in the future of cities might note a recent explosion of interest in the burgeoning suite practices broadly labelled ‘DIY urbanism’ where communities ‘on the cusp of crisis’ (Peck, 2012, p. 650) have started taking matters into their own hands. DIY urbanism can include a wide range of individual or collective, sanctioned or unsanctioned, long-lasting or ‘meanwhile’ activities such as guerrilla and community gardening; housing, food and education schemes and cooperatives; events, festivals and markets; alternative economies such as timebanks, local economies and bartering schemes; ‘empty spaces’ movements that occupy abandoned buildings for a range of purposes; or subcultural practices like graffiti, street art, skateboarding and parkour (see Iveson, 2013; Deslandes, 2013). DIY urbanism often takes place in ‘loose spaces’ that are given new meanings through uses that were never intended when they were created (Franck & Stevens, 2007). Thus, a vacant tower block has been used to stage an international arts festival, a storefront has been converted into a cultural centre, and a disused kiosk has been moved from place to place to serve as the operational base for a mobile community newspaper (Haydn & Temel, 2006). Median strips become gardens, carparks are turned into parklets, abandoned warehouses host fashion shows and art exhibitions, disused commercial fridges are used as libraries, and murals with community messages replace corporate advertisements. In this paper, we focus on a specific form of DIY urbanism: Temporary use. Bishop & Williams (2012, p. 5) have suggested that ‘Temporary is a difficult concept to pin down’ because nothing lasts forever. Thus, they have argued that temporary use should not be defined by its longevity but, instead, by the intention of the user(s). Similarly, Haydn & Temel (2006, p. 17) make a distinction between temporary use and other DIY urbanist approaches in that they are ‘planned from the outset to be impermanent’. This means that, unlike many ‘meanwhile’ and ‘interim’ projects, temporary use projects tend to include deconstruction and exit strategies, and they may use different building materials or methods for ease of deconstruction and relocation. This commitment to temporary uses can make it easier to solicit help from site owners who may otherwise be concerned about squatters and forced evictions. Given temporary use projects are designed not to last, it might be argued that they are essentially a waste of time. However, based on a case study Greening the Rubble (GtR) in Christchurch, New Zealand, we argue instead that it is precisely because the projects are temporary that certain goals have been achieved. These include activating policy-makers, promoting a more civil society, and enabling communities. The Case Study’s Shaky (Back)ground To understand how and why GtR formed (and the contribution their work makes to understanding the future of places), it is first necessary to understand the context. At 4.36am on the 4th September 2010, the Canterbury region of New Zealand was hit by the first of what was to be over 13,000 earthquakes. New Zealand is routinely affected by earthquakes and is known as the Shaky Isles and, based on experience, the country has very strict building codes around seismic strengthening. When the first major quake hit, despite experiencing ground forces among the highest ever recorded, most buildings in the city retained enough integrity to allow those inside to escape. Nonetheless, there were 185 direct fatalities and significant damage to homes and infrastructure. It was estimated that in the weeks immediately after the first earthquake approximately 70,000 people left Christchurch, New Zealand’s second most populous city, because their homes were uninhabitable, basic services were disrupted (Te Ara, n.d.) or they were deeply traumatised by the effects on sleep patterns, employment, schools and community life (Dupuis, Vallance and Thorns, 2014; Vallance and Carlton, 2014). Many people’s sense of ontological security was shattered. Following complex calculations around the likelihood of repeat events and the costs of repairing versus rebuilding, approximately 6 percent of homes and 75 per cents1 of Christchurch’s CBD has been slowly deconstructed and demolished. Ostensibly in order to undertake such a massive demolition programme safely, recovery authorities cordoned off acres of a once-bustling inner city, with residents and business owners prohibited from entry by the armed forces and police. The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) was formed by an Act of Parliament in April 2011 to oversee the recovery of the region, and decision-making authority ultimately rests with the Minister for Earthquake Recovery, (currently) Hon. Gerry Brownlee. While a series of other plans were developed for the wider region, he established the Christchurch Central Development Unit (CCDU) to oversee the redevelopment of the inner city. They, in turn, developed a 100 Day Plan – otherwise known as the Blueprint – ‘to help bring a renewed central city to life’ through proposed catalyst ‘anchor projects’ (www.cera.govt.nz). These legacy projects include large innovation, health, retail and convention centre precincts; a metro sports facility, library, cricket oval, cultural centre, bus exchange and an earthquake memorial. These massive - and massively expensive - projects, though grand, are controversial in that a) the 100 Day Pan was developed without public consultation, b) its implementation depends, in part, on the compulsory acquisition of private land and the displacement of many surviving residences and businesses, c) many residents would rather have quality infrastructure and rebuilt local community halls than a convention centre, and d) interest from the private sector has been lukewarm and, without private investment, it is not entirely clear who will pay for these projects to be completed. Methodology It was within this context that we began asking questions about the role of informal networks in recovery. Answering such questions demanded a flexible and sensitive methodology, and a deep familiarity with the setting. Mindful of concerns about the conduct of research and the ‘deadening’ effect that orthodox research approaches visit upon that which should be most lively (Lorimer, 2005), in this post-disaster context, we thought it most appropriate to adopt an iterative mix of research and analytic approaches. From different research traditions, but offering similar advice, Burns (2007) and Rappaport (2008) have developed an ‘orientation to enquiry’ which aims to make sense of a situation through experimental action. Research in this tradition expects that a range of 1 The numbers vary according to whether one looks at the percentage of buildings demolished or acreage cleared. both deliberate and spontaneous opportunities to gather data will be presented over the course of the project, as part of a process involving doing, learning through reflection, and ‘being in it’. Being in the research brings the benefits of enhanced understanding of the various components contributing to the issue at hand, and the ways in which they interact. The results of this research are, then, based on over three years of immersion in2 and involvement with the case study group: Greening the Rubble (GTR). GTR is a charitable trust dedicated to promoting biodiversity and community development in Christchurch city, by undertaking temporary projects on sites left vacant after the earthquakes. Numerous formal and informal interviews and observations took place over this time, along with reviews of internal correspondence and other information available to the public. Outcome to policy It is often assumed that broad transformation starts with policy, and policy leads to specific and intentional outcomes. Yet, here, we question this relationship with particular reference to the ways in which DIY urbanism and temporary use have been deployed to inspire, shape or even (preemptively) enact or perform policy. One of the easiest, and most common ways of documenting this kind of grassroots-led transition (if not transformation) is through the lens of urban renewal projects. There is now a growing body of scholarship exploring the ways in which formal urban renewal strategies have been sparked by informal and temporary projects, from pop up art galleries, craft studios, charity drives and reading rooms to food co-operatives and exchanges (Deslandes, 2013). Though some of this work is openly critical of the way successfully ‘turning a place around’ can lead to gentrification and, ironically, the displacement of those who seeded the renewal (Gerend, 2007; Colomb, 2012; Munzner and Shaw, 2015; Bader and Bialluch, 2008), even critics add credence to the argument that formal renewal policies can be sparked by temporary uses and DIY urbanists’ activities. Douglas (2014, p.5) has noted that activists sensitive to such critiques can be quite deliberate about promoting ‘explicitly functional and civic-minded informal contributions’. He notes, as an example, the way minor traffic incidents in the City of Pittsburgh were reduced after a ‘Cross Traffic Does Not Stop’ sign was erected by the Do-it-Yourself Department of Public Works. By creating public wishlists on vacant walls or painting official-looking “coming soon” signs for promised (but undelivered) neighbourhood amenities, Douglas notes DIY urbanists can enact policy changes that are broadly beneficial. At times, these are unsanctioned and pre-emptive, such as the installation of signs indicating cycles may be carried on subway trains, incorrect (lower) speed limit notifications, or the illicit painting of pedestrian crossings. Illicit or unsanctioned installations can also point out injustices or perceived inadequacies on the part of decision-makers (Figure 1). 2 The primary author is a founding GtR Board member and is currently Chair of this Charitable Trust. Figure 1: An unsanctioned dedication (Photo: Prefers to remain anonymous) Lydon has branded DIY urbanism with long-term goals and aspirations ‘tactical urbanism’ which, he argues, has five characteristics: • • • • • A deliberate, phased approach to instigating change; The offering of local solutions for local planning challenges; Short-term commitment and realistic expectations; Low-risks, with a possibly a high reward; and The development of social capital between citizens and the building of organizational capacity between public-private institutions, non-profits, and their constituents. (Lydon, 2011, p. 1-2). Though not all temporary uses are ‘tactical’ (to borrow Lydon’s (2011) framework), temporary uses can be seen as a tactic that may then be connected to strategic and formal planning ordinances, plans, policies and programmes. In some ways, however, this alignment of tactical urbanism to formal processes seems counter to the achievement of more radical transformation. Consequently, others have explored the ways in which more fundamental changes may be initiated in the loose spaces of temporary use. Németh and Langhorst (2014, p. 147) argue that temporary uses are able to expose ‘ongoing conflicts and contestations between competing value systems, interests, agendas and stakeholders, be they economic, social, ecological or cultural…[by] rendering visible the hidden mechanisms and machinations in the production of urban space’. They go on to argue that temporary uses may empower marginalised communities and provide them with a sense of participation in the creation of ‘place’ (Figure 2). Figure 2: GtR’s Pod Oasis or ‘Planty Hug’ (Photo: Jonathan Hall) This is a process from which they are often excluded by policy, regulatory and planning systems and rules governing land tenure, land use and occupation. This is a point that was made quite forcefully by a GtR contractor: I couldn’t imagine some of the sites that Greening the Rubble are operating from now - like the Sound Garden site which is literally around the corner from the Cathedral. I never ever imagined that as a landscaper I’d be involved in a project that was actually, you know to build a garden on that site. I mean that would have been amongst the most expensive real estate in the city and now we had an opportunity to put a garden there! Zardini (2008, p. 16) has argued that the ‘reoccupation of urban space with new uses’ facilitates the development of alternative lifestyles and the reinvention of daily life in cities (see Figure 3). While acknowledging the potential of DIY urbanism to reinvent life in cities and generate a wider politics, Iveson (2013, p.2) has argued that reoccupation – or, rather, ‘appropriation’ - is insufficient. Instead, he believes it is necessary to develop a shared focus around enacting the ‘right to the city’. Malloy (2009, p. 20-21) has suggested that temporary use can facilitate this providing innovative ways resisting the ‘dominating logic of free-market fundamentalism [that] corrodes social solidarity [and] rejects social justice … by poking holes in the dominant frame of the city as an avenue for competition and exchange’. Similarly, but from an emerging ‘insurgent planning’ perspective, Friedmann has argued that broader transformation can be achieved through ‘a process of selfdevelopment driven by small action-oriented groups – ephemeral good societies – bonded through dialogue and non-hierarchical relations, defending and enlarging the spaces for their own reproduction in the larger society’ (2011, p.5, italics added). Because they tend to focus on small, achievable projects, temporary uses (referred to by a local observer as ‘David’s pebbles’) present more accessible and varied ways of addressing the state’s blind spots or resisting corporate Goliath. Figure 3: Re-imagining broken places (Photo: Author) From aggregates of individuals to communities Civil society is a slippery notion and one that is more difficult to grasp in the face of post-modern concerns around unifying (silencing) discourses and God Tricks (Haraway, 1998). In this light, it is unlikely that there is one path to one civil society. Perhaps as a consequence, scholarship has started to look more closely at ‘situated knowledges’ (ibid) possessed by, and located in, various ‘communities’. Like ‘civil society’, ‘community’ is another term that is often used, but rarely interrogated. It has many meanings: Thorns (2002), for example, identified over ninety-four different definitions of community with people being the only common factor, though many emphasised shared values and common goals (see also Chamberlain, Vallance, Perkins and Dupuis, 2010). Though many equate communities with geographies, there has recently been much discussion around ‘post-place’ and on-line communities (see, for example, Bradshaw, 2009), and ‘communities of interest’. For the purposes of this discussion, we adopt Tocqueville’s distinction between ‘communities as aggregates of individuals’ on one hand, and as an ‘autonomous actor’ on the other. Using this distinction, Patterson, Weil and Patel (2010, pp. 128-29) have noted that as collections of individuals, communities ‘have only limited capacity to act effectively or make decisions for themselves, and they are strongly subject to administrative decisions that authorities impose on them. On the other hand, community as an autonomous actor, with its own interests, preferences, resources, and capabilities…[is able to use] institutions of civil society like churches, voluntary associations, the press, and so on [to] take immediate action to address issues that face them’. We use the term ‘community’ to indicate a non-governmental group or network capable of collective action (whether faith-based, sports-oriented, politically motivated or quite informal) noting that their aims can be diverse, and that they may intersect with formal state structures/vertical hierarchies in different ways. This raises questions about the relationship between temporary uses and community development; for example, can something temporary create more durable ‘communities’? Though not all temporary use projects are collective acts, many are. Such projects can therefore act as lightning rods, providing a focus for energy and ambitions that might otherwise be diffuse and formless. As Bishop and Williams (2012, p. 220) noted, temporary use projects can harness a ‘latent energy that can be tapped through a four-dimensional approach to urban planning and design’. People that may have been unconnected can - and do - come together around a project, whether to visualise and plan, implement, or undo. Whilst temporary, projects can assemble individuals unable to act alone into a collective capable of action. This, in fact, was how GtR was initially formed. The temporary project that seeded GtR was initiated a few weeks after the first earthquake (on the 4th September 2010) by the Canterbury Regional Council’s (ECan) Biodiversity Coordinator. He emailed an invitation to his contacts to ‘green the rubble’ by temporarily re-vegetating earthquake demolition sites. This, he suggested ‘would allow Christchurch communities to weave a response to the earthquake that merged rejuvenation and repair with the themes of the International Year of Biodiversity...’ (personal communication, Sept 2010). Within two months, a loose coalition of disparate but like-minded people (Vallance, 2013) broke ground on a temporary pocket park known as ‘Victoria Green’. While Victoria Green was a temporary park (albeit with a shorter lifespan than intended as it fell within the cordon put in place after the second major quake), the ‘loose coalition’ continued to strengthen: GtR is now in its 5th year, has become a Charitable Trust, and has just installed its 22nd project. Despite its focus on short-term projects, the development of this more durable organisation has stabilised a small community capable of collective action that is both direct (actual projects in real places) and tactical (engages with formal planning processes). This collective expands and contracts around specific projects, at times working with local communities or with more formal organisations, such as the Department of Conservation, to add capacity and capability. As one GtR affiliate explained: ‘Collaborated’ meant we had a common need which this space met and we helped each other according to our abilities. We all brought something to the project, we all got benefit out of the project and we all feel it’s our garden. These efforts can be both empowering and meaningful, as indicated by this observation from a GtR employee shows: [The projects] help bring people together and give them a sense of control that can otherwise seem lost in an over-regulated, up-scaled world. Because it is a very different category of projects, I mean you’ve got something that’s budget, ‘vernacular’ if you like, human-scale, volunteer labour. It’s the very opposite to convention centres built by machines. The future of cities: Permission to experiment, the right to fail, and the opportunity to succeed These case study results accentuate some key differences in the ways in which groups like GtR - with a focus on temporary use – and formal authorities work in practice. Many of these differences are neatly encapsulated by the ‘lighter, quicker, cheaper’ rubric promoted by Project for Public Spaces (www.pps.org. The lighter, quicker, cheaper approach has flow on effects; for example, it enables a broader participation in city (re)building and many of GtR’s projects have involved people who would not normally be part of this process: children and students, artists, sports groups, ethnic communities, people with disabilities, and ‘mature’ ladies with an interest in broken china (see Figure 4). Figure 4: The Green Room was a collaboration between GtR and Crack’d (Photo: author) This diversity of participants means that the city better reflects their interests and needs. It has been noted, for example, that more dancers feel a resonance with the city now (Figure 5). As Bishop and Williams (2012, p. 7) have argued, temporary uses constitute ‘a more dynamic, flexible and adaptive urbanism, where the city is …more responsive to new needs, demands and preferences of its users’. This is important in terms of resilience as it is an aphorism of systems thinking that monocultures are vulnerable. It could be argued that this applies to social systems as much as it does ecosystems. Figure 5: Owen Dippie’s ballerina mural (photo: author) One way is to see temporary use projects as a kind of social commentary or expression of issues people see as significant. Unlike many formal participatory processes (such as having the opportunity to make submissions on plans, hold a referendum, or run a survey) temporary use can be seen as a more engaging form of engagement able to solicit the views of demographics that are often hard to reach using more orthodox tools. Temporary uses are valuable in helping cities adapt to change in other ways too. Being closer to the ground also means tighter feedback loops are created; these feedback loops are a foundation of systems thinking and resilience (Walker and Salt, 2006). Lacking an elected mandate, temporary uses often have to be more careful about enlisting the support of others around them. In practical terms, this might mean iteratively making modifications that lead to improved outcomes as the project unfolds. Though they may seem obvious, it is worth teasing out other differences between informal and formal city re-building practices (Table 1). Temporary projects, being cheaper, quicker and diverse, tend to promote an experimental attitude, allowing trial runs and proof of concept prototypes. As one example, the idea of green roofs was a popular feature of the Christchurch City Council’s postquake Share an Idea campaign, but there were few working examples currently in Christchurch. GtR’s Green Roof project uses four small donated and relocatable buildings of about 12 m2 each. These act as demonstrations of green-roofed buildings though, as one volunteer noted, ‘They might end up being exemplars of what not to do! That’s still useful isn’t it’? Whether successful or not, the green roofs will contribute to a better understanding of this largely untested and unorthodox (in New Zealand) approach to urban agriculture. GtR Temporary Seeds Screws, paint, plants Opportunistic Unpaid labour Shoestring budget Social and cultural capital Quick Iterative, adaptable Guidelines Organic Low risk Experimental Responsive to context Fun Process Small-scale CERA/CCDU Legacy Anchors Concrete, steel and glass Deterministic Paid labour Big budget Financial capital Eventually, maybe Planned, programmed Instructions and Blueprints Bureaucratic High risk Orthodox, tried and tested Generic principles Necessary Product Comprehensive Table 1: Comparison of GtR and CERA/CCDU Temporary uses are also an important vehicle for social learning and capability development. Participation in this network has taught members various skills ranging from practical, on-site competence with a drill, to fundraising, website development, presentations, submissions on plans, human resource management, photography, accounting, landscape design, and so on. While there are clearly some projects and services that communities cannot undertake, our research suggests there is room to explore how the iterative, responsive, low-risk and adaptive approaches exemplified by temporary use groups might be included or modified to inform formal policy and planning for the future of places. We conclude with an example of how this ‘adaptive urbanism’ (see, for example, www.adaptiveurbanism.org.nz) might be applied in practice using a controversial project: The proposed Christchurch Convention Centre. It is currently unclear how CERA intends to fund the project given reluctance on the part of the Christchurch City Council to contribute financially, and the lukewarm response from the private sector. An alternative might be to seed the project by building a Centre within known and available budgets, but invite designs that have the potential grow if and when additional funding is secured. The design brief could also incentivise and support diversity by encouraging a broader range of uses and users than is traditional. Given the vulnerability of convention centre users during a disaster (as they are often from out of town), it could at least double as an evacuation centre for example. This could be achieved by adopting lighter and quicker, and possibly cheaper fixtures, such as moveable walls and seating, and building relationships with different groups (such as civil defence personnel). While this is just one, possibly quite trivial example, there is a broader message here for urban managers and practitioners about being more adapt-able, and accepting change as a normal part of everyday life. Seeing the potential of places, and being flexible about how they are used is a core characteristic of temporary use. We have argued that the adapt-ability such uses promote is key to the future of cities as it gives a greater number of people permission to experiment, the right to fail, and the opportunity to succeed. References Bader, I. and Bialluch,M. (2008). Gentrification and the creative class in Berlin-Kreuzberg. In L. Porter and K. Shaw (Eds.). Whose urban renaissance? pp. 93–102. London: Routledge. Bishop, P. and Williams, L. (2012). The Temporary City. New York: Routledge. Bradshaw, T. (2009). The post-place community: Contributions to the debate about the definition of community. Community Development, 2, 1, pp. 5-16. Burns, D. (2007). Systemic Action Research. A Strategy for Whole System Change. Bristol: The Policy Press . Chamberlain, P., Vallance, S., Perkins, H. and Dupuis, A. (2010). Community commodified: Planning for a sense of community in residential subdivisions. A paper presented at the Australasian Housing Researchers Conference, Auckland, 17-19th November, 2010. Colomb, C. (2012). Pushing the urban frontier: Temporary use of space, city marketing and the creative city discourse in 2000s Berlin. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34, 2, pp. 131- 152. Deslandes, A. (2013). Exemplary amateurism; Thoughts on DIY urbanism. Cultural Studies Review, 19, 1, pp. 216-225. Douglas, G. (2014). Do-It-Yourself urban design: The social practice of informal “Improvement” through unauthorized alteration. City and Community, 13, pp. 5-25. Dupuis, A., Vallance, S. and Thorns, D. (2014). On shaky ground: Homes as socio-legal spaces in a post-earthquake environment. A paper presented at the Sociological Association Aotearoa New Zealand conference, Christchurch 3-5th December, 2014. Franck, N. and Stevens, Q. (2007). Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life. London: Routledge. Friedmann, J. (2011). Insurgencies: Essays in Planning Theory. Oxon: Routledge. Gerend, J. (2007). Temps welcome: how temporary uses can revitalize neighborhoods. Planning, Magazine of the American Planning Association 12: 24-27. Haraway, Donna. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599. Haydn, F. and R. Temel. (2006). Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces. Basel: Birkhäuser. Iveson, K. (2013). Cities within the city: Do-it-yourself urbanism and the right to the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, pp. 941-956. Lorimer, H. (2005). Cultural geography: the busyness of being ‘more-than-representational’. Progress in Human Geography, 29, pp. 83–94. Lydon, M. (2011). Tactical Urbanism, Short-Term Action, Long-Term Change Volume 1. New York: The Street Plans Collaborative. Malloy, J. (2009). What is left of planning? In T. Schwarz and S. Rugare (Eds.). Pop Up City, pp. 19-38. Cleveland: Kent State University. Munzner, K. and Shaw, K. (2015). Renew Who? Benefits and Beneficiaries of Renew Newcastle. Urban Policy and Research, 33, pp. 17-36. Németh, J. and J. Langhorst. (2013). Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land. Cities on-line first, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275113000486 Patterson, O., Weil, F. and Patel, K. (2010). The role of community in disaster response: Conceptual models. Population Research and Policy Review, 29, pp. 127–141. Rappaport, J.( 2008). Beyond participant observation: Collaborative ethnography as theoretical innovation. Collaborative Anthropologies, 1, pp. 1-32. Te Ara (n.d.) Historic Earthquakes, The 2011 Christchurch earthquake and other recent earthquakes, p. 13. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/historic-earthquakes/page-13 Thorns, D. (2002). The Transformation of Cities: Urban Theory and Urban Life. Palgrave Macmillan: New York. Vallance, S. (2013). The artist, the academic, the hooker and the priest. A paper presented at the New Zealand Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Massey University, Auckland, 27-29th Nov, 2013. Vallance, S. and Carlton, S. (on-line first). First to respond, last to leave. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221242091400096X Walker, B. and Salt, D. (2006). Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Washington: Island Press. Zardini, M. (2008) A new urban takeover. In G. Borasi and M. Zardini (Eds.). Actions: What you can do with the City. SUN: Montreal.