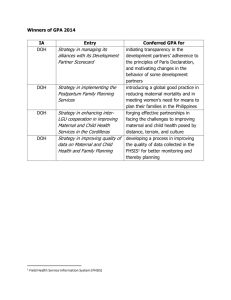

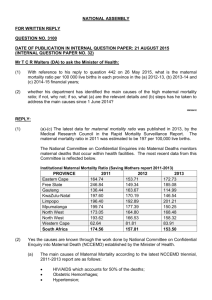

2. Appraisal Case

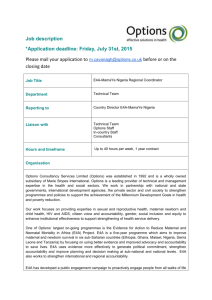

advertisement