Hate Crimes - University of Warwick

advertisement

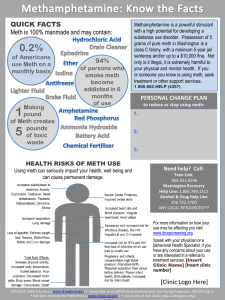

Drugs and Crime in the US: Evidence from a Shock in the Local Production of Crystal Meth VERY PRELIMINARY AND INCOMPLETE – WORK IN PROGRESS – NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION By ROCCO D’ESTE * (8 FEBRUARY 16) I investigate the effects of illicit drugs on crime, focusing on US state’s policies restricting the access to methamphetamine’s precursors chemicals. A diff-in-diff design reveals 10% to 15% reduction in property and violent crimes. I investigate the mechanisms showing: 34% and 16% drop in the arrests for possession and sale of synthetics drugs; 43% decrease in clandestine meth-labs seizures; 0.2 to 0.3 elasticity of crime to meth-labs; heterogeneous effects in states farther away from Mexico, the major “meth-exporter” into the United States. A separate analysis on hate crimes shows an increase only in violent episodes motivated by victims’ sexual preferences. I reconcile this finding with the psychosis from methwithdrawal and the widespread consumption of this substance within gay and bisexual communities. Keywords: Methamphetamine, Drugs, Crime, Hate-Crimes JEL Codes: K14, K42 •University of Warwick, Department of Economics, (e-mail: r.d-este@warwick.ac.uk). Special thanks for the support to Robert Akerlof, Dan Bernhardt, Mirko Draca, Rocco Macchiavello and Chris Woodruff. I gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the International Association of Applied Econometrics (IAAE) and the Royal Economic Society (RES). All errors and omissions remained are my own responsibility. 1 I. Introduction The total cost connected to the trafficking and abuse of illicit drugs in the United States is immense and hard to quantify, with an estimated annual economic loss for society of nearly $200 billion (ONDCP, 2007). The damage is reflected in an overburdened justice and healthcare system, lost productivity, environmental destruction and crime, with nearly 50% of all prison inmates being clinically addicted to some type of drug (NCADD, 2014). The proliferation of illicit drugs can lead to an increase in criminal offenses mainly through three different channels: 1) economic, due to the users’ need to support drug-habits; 2) systemic, due to the violence connected to the production and distribution of the drug itself and 3) pharmacologic, due to the psychotic behavior arising from drug’s effects (Goldstein, 1985).1 Nonetheless, while the shaping of cost-effective policy interventions needs a solid understanding and quantifying of these channels, very few studies have distinctly identified the existence of a causal link between the proliferation of illicit drugs and the propagation of crime.2 This paper contributes to the existing literature by focusing on crystal methamphetamine, an extremely addictive and neurotoxic substance, perceived to be as the most dangerous drug in the United States.3 I examine the effects on crime of US state level policies implemented as a reaction to a rapid proliferation in small toxic labs, where this illicit drug is produced. These policies restricted the access to methamphetamine precursor chemicals, ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, easily obtained through the chemical 1 2 3 Add note on other two indirect mechanisms Please read the “Relate Literature” subsection for more information. Add note on 500 sheriffs. 2 manipulation of cold tablets, which were freely sold over the counter prior to 2005. I build a comprehensive panel dataset for the analysis: 1,400 counties in 30 US states, from 1997 to 2010, including in the analysis a wide set of county, timevarying, socio-economic controls.4 I use a difference in differences design focusing on the effects of meth precursors states’ legislation on FBI reported crimes. I divide the empirical analysis into three main sections: 1) the direct analysis of the impacts of the laws on crime; 2) the exploration of the underlying mechanisms and 3) a separate analysis on hate crimes. I show a decline of 10% to 15% in both theft and violent crimes. These findings are robust to extensive checks, weighting the regression by a measure of the quality of the information on reported crimes, using different functional forms, adding to the analysis potential confounding controls and state time trends. I then explore the mechanisms behind these results in several ways. I detect a reduction of 34% in the arrests for possession and 16% in the arrests for sale of synthetic drugs. These findings suggest that precursors’ regulation is disrupting the market for those substances that are entirely created in clandestine laboratories, only through manipulations of chemical components. Falsification tests on marijuana, cocaine and heroin-related arrests do not reveal the presence of any spillover effects on these different drugs. I include data on clandestine labs seized by the police, a measure of the latent clandestine production of crystal meth in a county. Results show 43% decrease in clandestine meth-labs seizures. I then use this specification as a first stage regression in a two stage least square framework, where I estimate the effects of meth-labs on crime. I show an elasticity of both property and violent crimes to 4 Please refer to the Data section for a detailed description of all controls used in the analysis. 3 meth labs in the range of 0.2 to 0.3, with IV estimates 3 to 7 times higher in value than the Ordinary Least Square (OLS). I reconcile this difference to the presence of random noise and systematic measurement error in the county-level measure of the latent clandestine production of crystal meth. I hence test for the presence of heterogeneous effects on crimes across US states, employing a triple difference in differences strategy. The third interaction term is the distance of each US state from Mexico: the largest supplier to the U.S. illicit drug market, with Mexican drug traffickers earning approximately 25 billion USD each year in wholesale U.S. drug markets (U.N. World Drug Report, 2011). In particular, Mexican drug cartels accounts for as much as 80 per cent of the meth sold, suggesting that small clandestine labs do not fulfill the entire demand for this drug in the United States (DEA, 2010). While the lack of precise information related to the structure of drugtrafficking networks impose caution in the interpretation, I find some evidence suggesting the reduction in crime being stronger in states where drug users might rely more on the internal production of meth, (the one disrupted by the laws), rather than the Mexican one. I finally conduct a separate analysis on hate crimes: episodes of violence motivated by any sort of ethnic, religious, gender, sexual or other bias. I perform this analysis due to the possible connection between these somehow “irrational” violent crimes and the psychotic effects deriving from the abuse of crystal meth. Results show a controversial increase in violent episodes motivated by victims’ sexual preference, in particular against homosexuals, with no effect detected on any other hate crime. I reconcile these results with evidence related to the psychosis from meth withdrawal and the widespread consumption of this substance among gay and bisexual men, mainly as sexual stimulant. Overall, the results uncover a strong causal link between meth proliferation and the rise in criminal activity, suggesting that the economic, systemic and 4 pharmacologic channels, through which illicit drugs could cause crime, are all playing a role in this context. This work has the power to inform policy. Policymakers should take into account the extra benefit deriving from a reduction in crime, when contemplating cost and benefits of measures designed to disrupt the supply side of the market for drugs. Nevertheless, this study also suggests the need of carefully considering the demand side of the market, with a particular focus on communities where the abuse of the illegal substance is extremely acute. Violent side effects, in fact, might arise due to a drop in meth’s availability, not anticipated by a relative drop in users’ level of addiction. This paper unfolds as follows: section II describes the related literature; section III provides background information on methamphetamine effects, production and precursors’ legislation; section IV presents all the datasets used in the analysis, providing relative summary statistics; section V shows the results on crime and further explores the mechanisms; section VI offers the analysis on hate crimes; section VII concludes. II. Related Literature This paper adds to the existing literature on the determinants of crime in several ways. To the extent of my knowledge, this is one of the first papers offering a systematic empirical investigation on the effects of illicit drug propagation on the proliferation of criminal activity. The existing evidence supporting the theory that more drugs lead to more crime is somewhat inconclusive. Corman and Mocan (2000) using high frequency data for New York City show that drug usage has only a small effect on some property crimes. Despite the important of this study 5 as one of the first in this area, the time series dimension, coupled with the lack of a clear identification strategy, seems to represent a limit to the quality of this study. De Mello (2011) looks at the role of crack cocaine in explaining the aggregate dynamics in violence, using a fixed effect framework and adding timevarying controls. He hence relies on the exogeneity of the proportion of crackcocaine as a determinant in explaining crime, showing that crack explains 30% of the time series variation in the homicides in the state of Sao Paolo.5 By focusing on crystal methamphetamine, this study is closely related and complements two different works. The first, by Dobkin and Nicosia (2009), focuses on the effects in California of a different government effort to reduce the supply of methamphetamine precursors in 1995.6 While showing that methamphetamine price tripled, purity declined from 90 percent to 20 percent, amphetamine related hospital and treatment admissions dropped 50 percent and 35 percent, they do not find substantial reductions in property or violent crime. The second study, by Dobkin et al (2014), focuses on the same over the counter regulations studied in this paper, using a wide set of rich administrative datasets to detect the impact of the regulation of the number of labs, price, quality and consumption of the drugs. Consistent with my analysis, they show a decrease of meth-labs of 36%, but no effects on price, purity or consumption of methamphetamine. My study, while adding support to the results related to the disruption of methamphetamine market, look at the effects of precursors 5 Cracoland studio da citare, con risultati. Ma l’identification strategy e l’utilizzo di la predetermined sembrano a mio avviso un limite dello studio e rendono difficile la corretta interpretazione dei riultati 6 The Domestic Chemical Diversion Control Act (DCDCA) removed the record-keeping and reporting exemption for distributors of single-entity ephedrine products and empowered the DEA to deny or revoke a distributor’s registration without proof of criminal intent. In May 1995, the DEA shut down two suppliers that appear to have been providing more than 50 percent of the precursors used nationally to produce methamphetamine. This is probably the largest “supply” shock that has occurred in any illegal drug market in the United States and was made possible by the substantial concentration in the supply of methamphetamine precursors (Dobkin and Nicosia, 2009). 6 legislation from a different perspective, with an almost exclusive focus on the causal link between meth-proliferation and criminal activity.7 This study also adds to the literature related to the effects of drugs policy intervention. In a similar fashion, Melissa Dell (2012) examines the direct and spillover effects of Mexican policy towards the drug trade. In particular, she uses a regression discontinuity design to show that drug-related violence increases substantially after close elections of PAN mayors. Empirical evidence suggests that the violence reflects rival traffickers' attempts to usurp territories after crackdowns have weakened incumbent criminals.8 Finally, this paper adds to the existing literature by offering one of the first rigorous analyses of the determinant of hate crimes, linking them to the effects of crystal methamphetamines. Becker's seminal paper (1968) was the first to consider crime in an economic framework of rational behavior: agents maximize utility by comparing the benefits of crime with the relative costs. In this model, harm or loss to the individual is considered an externality, essentially an unintentional side effect of the offender's actions. In the case of a hate crime, however, it has been suggested that loss to the victim is the intention of the crime (Gale, Heath, and Ressler, 2002; Craig, 2002). The presumed irrationality of hate crimes could be explained by several factors that alter individual’s preferences. Along these lines, Machin et Hanes (2014) find significant increases in hate crimes against Asians and Arabs that occurred almost immediately in the wake of London and New York error attacks. They hypothesize that attitudinal changes resulting from media coverage may act as an underlying driver of the spike in hate crimes. 7 8 I also use county-year variation in the estimates, while their study exploits data grouped at the state level. Other similar studies are: 7 An alternative view is offered by contributions from behavioral economics. This suggests there may be some element of group interaction, such as peer pressure or the removal of social barriers, which causes individuals to commit hate crimes. My study adds to this literature an generally overlooked element: the abuse of highly addictive psychotic drugs in specific groups. This might lead feeling of anger and rage to dominate the individual's rational decision-making process, especially in closed communities, (in my case homosexuals and bisexuals), where the addiction is more severe. III. Background Information Methamphetamine Effects Methamphetamine is a powerful, highly addictive stimulant that affects the central nervous system. Also known as meth, chalk, ice, and crystal, it costs between $20-25 for ¼ of grams.9 The drug takes the form of a white, odorless, bitter-tasting crystalline powder that easily dissolves in water or alcohol.10 It can be smoked, snorted, injected, or ingested orally to produce a release of high levels of dopamine and neurotransmitters into the brain, generating sensations of self- 9 Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS, excluding ecstasy) remain seconds only to cannabis, with an estimated prevalence of 0.3-1.2 per cent in 2010, between 14.3 to 52.5 million users (UNODC, 2012). The United States government reported in 2008 that approximately 13 million people over the age of 12 have used methamphetamine—and 529,000 of those are regular users. It is a drug widely abused in the Czech Republic. There it is called Pervitin and is produced in small hidden laboratories and a limited number of larger ones. Consumption is primarily domestic but Pervitin is also exported to other parts of Europe and Canada. The Czech Republic, Sweden, Finland, Slovakia and Latvia reported amphetamines and methamphetamine as accounting for between 20% and 60% of those seeking drug abuse treatment. In Southeast Asia, the most common form of methamphetamine is a small pill—called a Yaba in Thailand and a Shabu in the Philippines. More info at: http://www.drugfreeworld.org. 10 The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration has classified methamphetamine as a Schedule II stimulant, which makes it legally available only through a no refillable prescription. Medically it may be indicated for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and as a short-term component of weight-loss treatments, but these uses are limited and it is rarely prescribed. 8 confidence, energy, alertness, pleasure, and sexual arousal. The high from methamphetamine lasts from 8 to 24 hours while, in comparison, the high from cocaine lasts from 30 minutes to one hour. With repeated use, meth exhausts accumulations of dopamine in the brain, simultaneously destroying the wiring of dopamine receptors.11 This process is what makes crystal meth extremely addictive, leading frequent users towards the physical impossibility of experiencing pleasure, (a condition known as anhedonia), and the consequent intense craving for the drug itself. Chronic abuse can lead to psychotic behavior, hallucinations, paranoia, violent rages, mood disturbances, suicidal thoughts, insomnia, psychosis, poor coping abilities, sexual dysfunction, dermatological conditions and "meth mouth", a dental condition characterized by severe decay and loss of teeth, fracture and enamel erosion (NIDA, 2002). The termination of use can result in depression, fatigue, intense craving for methamphetamine, anxiety, agitation, vivid or lucid dreams, suicidal temptation, psychosis resembling schizophrenia, paranoia and aggression (ONDCP 2003). Since meth withdrawal is extremely painful and difficult, most abusers revert: 93% of those in traditional treatment return to abusing methamphetamine (Drug Free World, 2014). Methamphetamine Production and Precursors’ Legislation Unlike heroin or cocaine, methamphetamine is a synthetic product can be easily and inexpensively manufactured within the U.S. with little equipment, few 11 Although both methamphetamine and cocaine increase levels of dopamine, administration of methamphetamine in animal studies leads to much higher levels of dopamine, because nerve cells respond differently to the two drugs. Cocaine prolongs dopamine actions in the brain by blocking the re-absorption (re-uptake) of the neurotransmitter by signaling nerve cells. At low doses, methamphetamine also blocks the re-uptake of dopamine, but it also increases the release of dopamine, leading to much higher concentrations in the synapse (the gap between neurons), which can be toxic to nerve terminals (National Institute of drug abuse, 2014). More info at http://www.drugabuse.gov. 9 supplies, and almost no expertise in chemistry. 12 Methamphetamine’s main ingredient is ephedrine or pseudoephedrine that, if not already in pure powder form, it must be separated from the tablets of cold medicine that contain it. For this purpose, cold tablets are mixed to sodium hydroxide, anhydrous ammonia, iodine, matches containing red phosphorus, Drano (a drain cleaner product), ether, brake and lighter fluid and hydrochloric acid. All these are legal products, which can be easily bought in different stores. The entire chemical process, usually undertaken in self-made chemical labs hidden in flats, caravans, garages or hotel rooms, generally takes about two days' time and can result in hundreds of thousands of methamphetamine doses. The production process involving a dangerous mixture of highly corroding and inflammable chemicals creates a set of unique problems for the environment and the community (Weisheit et al, 2010).13 Because of the concentration in the meth production of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, the federal government has passed, in the last 25 years, several laws intended to cut the diversion of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine to illegal drug labs.14 This paper examines the effects of state-level policies implemented, 12 Insert here a bit of story of meth production citing the paper. 13 Methamphetamine laboratories pose environmental and health risks that transcend the effects of the drug on the user. Apartment residents may be killed or injured by a meth lab explosion in the adjoining apartment, children in homes where meth is cooked may be exposed to toxic chemicals and to meth itself, hotel guests may be injured by toxic chemical residue from the previous tenant’s meth lab, children may be burned or seriously injured by the meth trash dumped along the roadways near their homes, and emergency responders may be sickened when they enter a lab site. Further, producing one pound of methamphetamine generates five to six pounds of toxic waste (Hargreaves 2000), waste that may contaminate the ground or water supplies. Thus, meth labs pose a type of threat to innocent citizens that simple drug use does not. 14 The first of these was the Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act of 1988 (CDTA), which regulated ephedrine and pseudoephedrine in bulk powder form, but left processed forms unregulated. This was followed by the Domestic Chemical Diversion Control Act of 1993, which placed restrictions on OTC ephedrine products (e.g. tablets) and increased DEA oversight of suppliers. Then, the Methamphetamine Control Act of 1996 tightened regulations on the sale of products containing methamphetamine precursors over 24 grams, but contained an exception for “blister packs”. Shortly thereafter, the Methamphetamine Anti-Proliferation Act of 2000 lowered the thresholds from 25 to 9 grams, but blister packs remained exempt. Each of these federal efforts induced methamphetamine producers to switch to sources of precursors that remained unregulated (Dobkin et al., 2013). 10 in the year 2005, in reaction to a rapid increase in small toxic labs.15 These policies focused on controlling access to the methamphetamine precursor chemicals ephedrine and pseudoephedrine through retail transaction quantity restrictions, sales environment restrictions, purchase and possession penalties, and agency responsible for enforcing precursor policies. 16 [Table 1] Table 1 shows the effective date of enactment of the laws for each state included in the analysis. IV. Data and Summary Statistics In my main analysis, I use county level data on crime rates, arrests and sociodemographic variables, from 1997 to 2006. I exclude the last 4 years of the sample due to the implementation of the federal Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act, with the last provision of the law taking effect on the 30th of September 200617. This law did not pre-empt more restrictive state policies.18 I use several data sources that I separately describe in this section. 15 Policy activity directed at limiting access to methamphetamine precursor chemicals has not been limited to the state level Federal legislation took place in 2006 through the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act that became effective the 8th of April 2006 (Federal purchase quantity limits) and the 30th of September 2006 (Federal clerk intervention requirements). Importantly, federal intervention did not pre-empt more restrictive state policies. 16 Data are available for 32 US States and are obtained trough McBride et al. 2011. The States included in the analysis are: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Given the scope of the empirical exercise, I do not differentiate across specific types of legislation. Jean et al. (2009) provide a detailed analysis of the legislations enacted by each state. 17 While this law does not allow for the analysis of the long run effect of the state laws on crime, it can be seen as a further natural experiment where the treatment states become control states and vice versa. The results of this specification are quite inconclusive and are shown in the appendix of the paper. 18 The Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 (CMEA) was signed into law on March 9, 2006, to regulate, among other things, retail over-the-counter sales of ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine products. Retail provisions of the CMEA include daily sales limits and 30-day purchase limits, placement of product out of direct customer access, sales logbooks, customer ID verification, employee training, and self-certification of regulated sellers. The CMEA is found as Title VII of the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-177). 11 Reported Crimes And Data on Arrests County level data on reported crimes, arrests and number of sworn police officers and civilian employees19 is accessed through the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data.20 The eight different types of reported crimes are: larceny, burglary, robbery, motor-vehicle theft, murder, aggravated assault, rape and arson.21 I also analyze data on arrests for sale and possession of drugs: synthetic drugs, opium/cocaine, marijuana, and other dangerous non-narcotics. I have collected these data from 1997 to 2010. Hate Crimes The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Hate Crime Statistics (HCS) provides incident-level data on hate crimes in which each case represents a single incident report, from which I construct county-level hate-crime measures. The Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990 brought these data into existence. That Act requires the Attorney General to collect annual data on “crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, including where appropriate the crimes of murder, non-negligent manslaughter; 19 Sworn police officers are law enforcement employees with arrest powers. Civilian employees include personnel employed by each local agency who do not have arrest powers and include job classifications such as clerks, radio dispatchers, meter maids, stenographers and accountants. 20 Data are downloadable at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/content/NACJD/guides/ucr.html#desc_cl. 21 County-level files are created by NACJD based on agency records in a file obtained from the FBI that also provides aggregated county totals. NACJD imputes missing data and then aggregates the data to the county-level. The FBI definition of the eight types of crime, as well as the explanation of the hierarchy rule, can be found in the data appendix. In the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, property crime includes the offenses of burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson. The property crime category includes arson because the offense involves the destruction of property; however, arson victims may be subjected to force. Because of limited participation and varying collection procedures by local law enforcement agencies, only limited data are available for arson. In the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, violent crime is composed of four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. Violent crimes are defined in the UCR Program as those offenses that involve force or threat of force. 12 forcible rape; aggravated assault, simple assault, intimidation; arson; and destruction, damage or vandalism of property”. I have collected these data from 1997 to 2010. Meth Labs Seizures The National Clandestine Laboratory Register, provided by the US department of Justice, contains – from 2004 onwards – the dates and addresses of the locations where law enforcement agencies reported they found chemicals or other items that indicated the presence of either clandestine drug laboratories or dumpsites. I use this information to create a county annual measure of the number of meth labs seized by the police. TEDS – Treatment Episode Data Set The Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) is maintained by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The TEDS system includes state level records for some 1.5 million substance abuse treatment admissions annually. While TEDS does not represent the total national demand for substance abuse treatment, it does comprise a significant proportion of all admissions to substance abuse treatment, and includes those admissions that constitute a burden on public funds. Data are collected from 1997 to 2010. Socio-Economic Controls I add a wide set of county time-varying socio-economic controls, obtained from the US Census Bureau22 and from the Bureau of Labor Statistics-Current 22 I use http://censtats.census.gov/usa/usa.shtml. 13 Population. I include income per capita, percentage of people below the poverty line, percentage of unemployment, the number of social security recipients and the average monthly payment per subsidy. I also add the number of commercial banks and saving institutions in the county, the number of pawnshops,23 the amount of banking and saving deposits, the population density and the racial/ethnic composition in the county24 Summary Statistics Summary statistics for all the crime and drugs-related variables are shown in table 2A. I define all these variables in terms of rates per 100,000 inhabitants. [Table 2A] Larceny is most frequent property crime, with a mean of 1,981 and a standard deviation of 3,121, followed by burglary, motor-vehicle theft and arson. For what concerns violent crimes instead, aggravated assault is the most frequent, followed by robbery, rape and finally murder. I also show summary statistics for possession and sale of drugs, separately. These will be another outcome of the analysis, and include marijuana, crack cocaine, synthetic and other drugs. Top of the list in both cases is marijuana followed by crack cocaine. I can observe the same type pattern for the number of hospital admissions, with the top substance being alcohol. Nevertheless, these numbers hide the enormous growth that methamphetamine has had overtime. Table 2b shows the annual growth rate of a pooled measure of the arrests, both for sale and possession, of marijuana, crack cocaine and synthetics. 23 Infogroup provided the overall number of pawnshops by county, per year. See d’Este (2014). 24 The racial origin is defined according to four categories: White, Black, Asian and Indian American. Moreover each race is divided into Hispanic or Not Hispanic ethnic origin. 14 [Table 2B] Before 2004, synthetic-related arrests displayed an impressive increase of more than 100%, with the arrests for the other type of drugs displaying a more stable pattern. Finally, I report the ranking of all the 50 US States related to the normalized number of methamphetamine related hospitalization. Hawaii, Iowa, Montana, South-Dakota being first in the list, with the problem being more widespread in the south and in the center of the United States rather then in the coast.25 [Table 3] Table 3 reports the descriptive all socio-economic controls used in the analysis. For brevity, I omit discussion of summary statistics of these variables. V. Empirical analysis In this part of the paper I will proceed as follows: first, I will present the baseline difference in differences approach on the effects of the states’ law on crime; then I will start to explore the mechanism showing: the results on drugsrelated arrests; the result on meth labs seizures and the instrumental variable approach; a triple difference in differences to investigate the differential impact of the law on crime in US states farther away from Mexico. 25 FBI evidence on Hawaii 15 Difference in Differences Approach I start to use a standard difference in differences approach using the following estimating equation: ′ 𝑦𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖 + 𝜇𝑡 + 𝑋𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 𝛽0 + (𝑡𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑 ∗ 𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡)𝛽1 + 𝜖𝑖,𝑠𝑡, (1) where i indicates the county, s the state and t the year. The outcome of interest is the number of reported crimes, with a separate regression for each type of crime. Reported crimes are expressed as a 𝑙𝑜𝑔(1 + 𝑥) where 𝑥 is the number of crimes normalized per 100,000 people. The analysis focuses on 𝛽1, the interaction between a dummy indicating a treated state and a dummy indicating the period after which the law was enacted. In this case, the variable post takes the value 1 in 2005. Standard errors are clustered at the state-year level. The inclusion of county fixed effects 𝛼𝑖 control for time-invariant unobserved characteristics both related to the changes in crime and the states’ decision of enacting the law. Year fixed effects 𝛾𝑡 capture common shocks across the entire sample. I finally add a vector of county time-varying socioeconomic controls ′ 𝑋𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 , described in the previous section. [Table 4] Results for this specification are shown in Table 4 panel A, where I include a column for each crime. This specification detects a differential reduction in murders and robberies in treated states, after the enactment of the law. I detect a reduction of 12% and 18% of murders and robberies, both significant at the 1% level. While I do not detect any effect on any other crime, the negative coefficient on burglaries has a p-value of 13%. 16 Table 4 panel B shows the results of the same specification, adding as a control the number of sworn police officers and civilian employees, the number of public hospitalization for crack-cocaine, marijuana, heroin and medicines bought over the counter. The decision of analyzing the results separately depends by the fact that these controls might be, for different reasons, potential outcomes of the law.26 Adding these controls barely change the point estimates of the baseline regression, increasing the precision for burglaries at a 10% significance level. Table 4 panel C shows the results where potential outcomes and state linear trends are included. The inclusion of state linear trends increases the precision of the estimates. Using this specification, a 13% reduction of larcenies, a 14% reduction of burglaries and robberies, all significant at the 1% level. While the coefficient on murders looses its significance I detect a drop in aggravated assault of 9% significant at the 10% level. Table 5 shows the results of the baseline specification with the inclusion of the interaction between the variable treated multiplied by a dummy for each year, excluding the dummy for the first year of the sample. [Table 5] While the inclusion of all these interaction creates collinearity across regressors, I do not observe any particular trend in specifications for larceny, burglary, robbery and murder. In Table 6 I restrict the analysis from 2003 to 2006, creating a balanced analysis of two years before and after the laws’ enactment. [Table 6] I detect strong negative results for larceny, burglary, murder and robbery, oscillating from 6% to 17%, all significant at the 1% level. I also detect an 8% 26 Discuss the reasons. 17 reduction in aggravated assaults and 6% drop in motor-vehicle thefts, significant at the 5% and 10% level. Analysis of Drugs-Related Arrests I investigate the mechanism performing a further analysis on a different set of outcomes: arrests for sale and arrests for possession of crack-cocaine, marijuana, synthetic and other drugs. Results for this specification are shown in table 7. [Table 7] I detect a 34% and a 16% drop in the arrests for possession and sale of synthetic drugs but no effects on marijuana, crack-cocaine and heroin arrests. These results, while showing a strong effect of the laws only on synthetic-related arrests, strengthen the validity of the hypothesis presented in the paper. Moreover, the lack of spill over effects across different type of drugs, seems to suggest the uniqueness of methamphetamine production process and its diversity from the production and, most likely, distribution of all the other drugs. Meth-Labs Seizures and IV approach I extend the analysis introducing a county measure of the latent local production of methamphetamine. For this reason, I include in the analysis the number of clandestine meth-labs, seized by the police, available from 2004 onwards. For each county in every year I instrument the log of the normalized number of meth-labs seized by the police, using the interaction of the treated*post dummy. The baseline IV model is given by the following two equations system where (3) is the first stage and (2) is the second stage. 18 ′ ̂ 𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 𝛽1 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 𝑦𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑠 + 𝛿𝑡 + 𝑋𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 𝛽0 + 𝑚𝑒𝑡ℎ_𝑙𝑎𝑏𝑠 (2) ′ 𝑚𝑒𝑡ℎ_𝑙𝑎𝑏𝑠𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 = 𝛾𝑠 + 𝜂𝑡 + 𝑋𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 𝛽2 + (𝑡𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑡 ∗ 𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡)𝛽3 + 𝜁𝑖,𝑠,𝑡 (3) Reported crimes and methamphetamine labs are expressed in the form 𝑙𝑛(1 + 𝑥), where 𝑥 is the number of crimes or the number of labs expressed per 100,000 inhabitants. Due to data availability and the implementation of the federal law, I include in the analysis 3 years of the sample, from 2004 to 2006. For this reason, I also omit from the baseline specification county fixed effects, which will be added back as a robustness check together with state-linear trends. [Table 8] Table 8 shows the results of the first stage. The sign of the coefficient is negative as expected. The introduction of the law reduces by 43% more the number of labs seized by police in treated states. This reduction is significant at the 1% level. Moreover, the Kleinbergen-Paap Wald F-statistic on the excluded instrument has a value of 67.26 an extremely reassuring value that excludes the bias arising from the use of a weak instrument. Table 9A and 9B show the OLS and IV result for property and violent crimes. [Table 9A – 9B] For the case of property crimes, the elasticity on larceny and burglary is positive 0.2 and 0.3 significant, in both cases, at the 5% level. The elasticity in case of motor-vehicle thefts is 0.15 with a p-value of 13%. For violent crimes, I detect a 0.27 elasticity on robbery, significant at the 10% level, and an elasticity of 0.23 for murder with a p-value of 15%. The IV estimates are 3 to 4 times higher than the OLS estimates. A reason for that can be related to the presence of idiosyncratic measurement error in the count of methamphetamine labs and to a plausible systematic over representation of seized 19 meth labs in treated states where police could have become tougher on this problem.27 Distance from Mexico In this part of the paper I investigate for the possible presence of a heterogeneous effect of the laws, taking into account the distance from Mexico, the major exporter of methamphetamine into the United States. Mexican drug cartels are filling the void in the nation's drug market created by the long effort to crack down on American-made methamphetamine, flooding U.S. cities with exceptionally cheap, extraordinarily potent meth from factory like "super labs." Although Mexican meth is not new to the U.S. drug trade, it now accounts for as much as 80 per cent of the meth sold here, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. To test for the possibility of a differential impact of the US States’ laws on crime, I employ a triple difference in differences strategy, using the triple interaction given by the treated and post dummy, and a measure of the distance of the State from Mexico. Results for larceny, burglary, robbery and murder are shown in Table 10. This specification captures a negative and significant result of the triple interaction term on larcenies and burglaries. [Table 10] The crime reducing effect of the law is higher in US States further away from Mexico. While I do not want to over-emphasize the significance of these results do to the lack of precise information related to the composition of the networks of drug trafficking, I consider this as an interesting venue for future research. 27 Description systematic measurement error and mccrary findings. 20 VI. Hate Crimes and Crystal Meth In this section of the paper I try to further explore the link between methamphetamine proliferations and hate crimes. These crimes are biasmotivated, which the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990 defines as “offenses against a person or property motivated by bias toward race, religion, ethnicity/national origin, disability, or sexual orientation” Table 11 shows the distribution of episodes in the United States from 1997 to 2010, by type of bias. Hate crimes’ episodes are mainly divided in crimes against: black 36%, white 10%, Jewish 11%, Hispanic 7%, Homosexuals 10%.28 [Table 11] Hate Crimes are mainly violent crimes. The distribution of these crimes by type of offense is shown in Table 12 with destruction/vandalism representing 33% of episodes, intimidation 30%, simple assault 18% and aggravated assault 10%. [Table 12] Crystal Meth in the Gay and Bisexual Community Methamphetamine use and risky sexual behavior have been connected in several studies of gay and bisexual men (Colfax et al., 2005; Drumright et al., 2006; Fernández et al., 2007; Plankey et al., 2007; Purcell et al., 2005; Vaudry et al., 2007). Methamphetamine use is associated with numerous sexual risk factors including behavioral disinhibition, enhanced sexual desire, low rates of condom use, high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), increased desire for high 28 All the categories and the relative distribution are shown in Table 11. 21 risk activities, prolonged sexual activity, multiple partners, and casual or anonymous sexual partners (Colfax et al., 2005; Molitor, Truax, Ruiz, & Sun, 1998; Shoptaw, 2006). In a recent review article, Drumright, Patterson, and Strathdee (2006) posited that a causal relationship between methamphetamine use and HIV-positive status is likely to exist, which implicates methamphetamine use as a major public health concern. Table 13 shows the results of a difference in differences specification. The first column reports the results on the overall number of hate crimes while, from column 2, I display the results for the most frequent hate crimes: Anti-White, Anti-Black, Anti-Jewish, Anti-Islamic, Anti-Homosexual, Anti-Heterosexual, Anti-Physical Disability. [Table 13] Panel A reports the results from the baseline diff-in-diff specification, in Panel B I add state trends, In Panel C I log transform the outcome variables, always including state linear trends in the specification. Results in each panel show a positive effect, significant at the 1%, on violent episodes against homosexuals and against heterosexuals (only insignificant in the first specification with a p-value of 15%). No significant result, across all the different specifications, is detected on other hate crimes. Despite the difficulty to explain the mechanisms behind these findings, the analysis clearly indicates the presence of some positive response after the enactment of the law related to the meth abuse and the sexual activity. These results suggest the importance of considering side effect to the implementation of laws restricting the production of an extremely addictive drug, without shifting as well the level of addiction of drug users condensed in certain communities. 22 VII. Conclusions This paper offers one of the first systematic empirical investigations of the effect of the proliferation of illicit drugs on criminal behavior. Motivated by the richness of anecdotal evidence, I look at this issue through the lens of crystal methamphetamine, a neurotoxic illicit substance widely diffuse in the United States and in the rest of the world. I use as a source of variation state-level policies restricting the access methamphetamine precursor chemicals. A mixture of diff-in-diff and IV approaches shows: 1) a reduction of property and violent crimes of 10% to 15%; 2) a 43% decrease in clandestine meth-labs seizures and 3) an underlying crime’s elasticity of around 0.3; 4) a 34% and a 16% drop in the arrests for possession and sale of synthetic drugs; 5) no spill-over effects on arrests for sale or possession of other drugs. I also test for the presence of differential effects in states farther away from Mexico, and I conduct separate analysis on hate crimes, showing a sharp increase only on violent episodes related to the sexual orientation of the victims. This paper suggests new directions for future research. A direct spin off of this work would be the analysis of shocks on the supply, distribution or consumption of other dangerous drugs such as crack-cocaine and heroin. Moreover, entering the “black box” of the mechanism linking proliferation of drugs and criminal activity is critical for the understanding of criminal behavior. Three main mechanisms seem in fact to play an important role in this context: economic, systemic and psychological. Disentangling these three channels might help to shape specific policy interventions that seek to reduce the impact that the proliferation of drugs can have on criminal behavior. This and other interesting aspects are left for future research. 23 REFERENCES Becker, G. (1968) Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach, The Journal of Political Economy, 76, 169-217. Becker, Gary S., Kevin M. Murphy, and Michael Grossman. "The market for illegal goods: the case of drugs." Journal of Political Economy 114.1 (2006): 38-60. Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Chesney M, Vittinghoff E. the EXPLORE Study Team. “Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men.” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005; 82:i62–i70. Corman, Hope, and H. Naci Mocan. "A Time-Series Analysis of Crime, Deterrence, and Drug Abuse in New York City." American Economic Review (2000): 584-604. Craig, K. (2002) Examining Hate-Motivated Aggression: A Review of the Social Psychological Literature on Hate Crimes as a Distinct Form of Aggression, Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 7, 85-101. d’Este, Rocco. “The Effect of Stolen Goods Markets on Crime: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment.” No. 1040. University of Warwick, Department of Economics, 2014. De Mello, J.. Assessing The Crack Hypothesis Using Data From A Crime Wave. REAP Working Paper, N. 003, 2011. Dell M. Trafficking Networks and the Mexican Drug War. 2011. Disha, Ilir, James C. Cavendish, and Ryan D. King. "Historical Events and Spaces of Hate: Hate Crimes against Arabs and Muslims in Post-9/11 America." Social 24 Problems 58.1 (2011): 21-46. Dobkin, Carlos, Nancy Nicosia, and Matthew Weinberg. "Are Supply-Side Drug Control Efforts Effective? Evaluating OTC Regulations Targeting Methamphetamine Precursors." Dobkin, Carlos, and Nancy Nicosia. "The war on drugs: methamphetamine, public health, and crime." The American economic review 99.1 (2009): 324. Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MRG, Malcarne VL, Daar ES, Gorbach PM. “Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006; 43: 344–350. Fernández MI, Bowen GS, Warren JC, Ibañez GE, Hernandez N, Harper GW, Prado G. Crystal methamphetamine: a source of added sexual risk for Hispanic men who have sex with men? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007; 86:245–52. Gale, L., W. Heath and R. Ressler (2002) An Economic Analysis of Hate Crime, Eastern Economic Journal, 28, 203-216. Goldstein, Paul J. "The drugs/violence nexus." Crime: Critical Concepts in Sociology 4 (2003): 96. Halkitis PN, Fischgrund BN, Parsons JT. Explanations for methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men in New York City. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005; 40:1331–1345. Halkitis PN, Mukherjee PP, Palamar JJ. Multi-level modelling to explain methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men. Addiction. 2007; 102:76– 83. Hanes, Emma, and Stephen Machin. "Hate Crime in the Wake of Terror Attacks: Evidence From 7/7 and 9/11." (2013). Hser, Y. I., D. Huang, M. L. Brecht, et al. (2008). "Contrasting trajectories of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use." Journal of Addictive Diseases 27(3): 13-21. 25 Jean, O’Connor, Jamie Chriqui, Duane McBride, Carissa Baker, Yvonne TerryMcElrath, and Curt Vander Waal. "From Policy to Practice: State Methamphetamine Precursor Control Policies." McBride, Duane C., Yvonne M. Terry-McElrath, Jamie F. Chriqui, Jean C. O'Connor, Curtis J. VanderWaal, and Karen L. Mattson. "State methamphetamine precursor policies and changes in small toxic lab methamphetamine production." Journal of Drug Issues 41, no. 2 (2011): 253281. Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, Cox C, Li X, Peck JA, Jacobson LP. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007; 45:85–92. Purcell DW, Moss S, Remien RH, Woods WJ, Parsons JT. Illicit substance use, sexual risk, and HIV-positive gay and bisexual men: differences by serostatus of casual partners. AIDS. 2005; 19:S37–S47. Ryan, Matt E., and Peter T. Leeson. "Hate groups and hate crime." International Review of Law and Economics 31.4 (2011): 256-262. Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002; 22:149–156. Shoptaw S. Methamphetamine use in urban gay and bisexual populations. Topics in HIV medicine. 2006; 14:84–7. Shukla, Rashi K., Jordan L. Crump, and Emelia S. Chrisco. "An evolving problem: Methamphetamine production and trafficking in the United States." International Journal of Drug Policy 23.6 (2012): 426-435. United Nations International Drug Control Programme and United Nations Office on Drugs and United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (2011): World Drug Report, United Nations Publications. 26 United States Drug Enforcement Agency (2011): Drug Trafficking in the United States. Vaudrey J, Raymond HF, Chen S, Hecht J, Ahrens K, McFarland W. Indicators of use of methamphetamine and other substances among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2003–2006. Drugs and Alcohol Dependence. 2007; 90:97– 100. Weisheit, Ralph A., and L. Edward Wells. "Methamphetamine laboratories: The geography of drug production." W. Criminology Rev. 11 (2010): 9. 27 TABLES TABLE 1: STATES' LEGISLATION (MCBRIDE ET AL., 2011) States Date Enacted Date Effective ALABAMA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO FLORIDA GEORGIA HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY MICHIGAN MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEWYORK NORTHCAROLINA NORTHDAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA SOUTHDAKOTA VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WISCONSIN WYOMING 05/24/2005 05/20/2005 03/30/2001 10/10/1999 05/27/2005 06/01/2005 04/19/2005 07/05/2005 None 08/24/2004 05/10/2005 03/22/2005 04/15/2005 03/18/2005 None 07/01/2005 06/15/2005 05/02/2005 05/31/2005 None None 09/27/2005 04/22/2005 None 04/06/2004 08/16/2005 None 02/25/2005 None 05/11/2005 06/07/2005 03/15/2005 05/07/2005 08/12/2005 03/30/2001 01/01/2000 07/01/2005 07/01/2005 07/01/2005 07/01/2005 None 01/01/2005 07/01/2005 05/21/2005 06/01/2005 06/01/2005 None 07/01/2005 06/15/2005 07/01/2005 09/05/2005 None None 09/27/2005 04/22/2005 None 04/06/2004 08/16/2005 None 07/01/2005 None 10/01/2005 06/21/2005 07/01/2005 28 TABLE 2 – CRIMES AND DRUGS DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS (1) Mean (2) Standard Deviation 28.98 29.72 11.96 19.11 74.99 43.38 31.22 137.7 58.28 226.1 24.80 46.40 214.3 210.4 50.90 226.9 Larceny Burglary Robbery Motor/Vehicle Theft Murder Aggravated Assault Rape Arson 1,984 659.0 61.98 215.2 4.516 223.0 27.35 19.25 3,121 991.2 396.8 790.9 28.88 417.3 40.80 52.61 Sworn Police Officers & Civilian Employees 81.2 54.6 28640.5 2366.5 556.5 13626.2 15719.3 4486.2 76.6 38214.03 2542.4 1685.4 23539.4 16984.2 12804.7 105.7 Arrests for Sale Cocaine Marijuana Synthetic Others Arrests for Possession Cocaine Marijuana Synthetic Others Reported Crimes Measures of addiction Alcohol Methamphetamine Amphetamine Cocaine Marijuana Heroin Over the Counter 29 TABLE 2 B – ARRESTS FOR SALE AND POSSESSION 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Marijuana Synthetic Cocaine 3.34% 0.65% 0.34% -5.56% -0.34% 5.32% 3.97% 0.98% 2.52% -4.45% -9.00% 1.15% -3.60% 16.14% 5.26% 12.87% 20.60% 15.67% 3.62% 12.41% 4.99% -12.34% -7.85% -10.57% 20.46% 3.17% 3.61% -8.91% -1.67% -5.34% 4.42% 3.52% 6.22% 9.49% 6.69% -11.64% -19.24% -12.85% -10.48% Note: This table shows the percentage change of the number of arrests from t-1. Year 1998 is computed using 1997, omitted from the table 30 TABLE 2C – METH-RELATED HOSPITALIZATION, BY STATE HAWAII IOWA MONTANA SOUTHDAKOTA CALIFORNIA WYOMING IDAHO UTAH NEBRASKA NEVADA KANSAS WASHINGTON OREGON MINNESOTA COLORADO OKLAHOMA MISSOURI NORTHDAKOTA ARKANSAS ARIZONA INDIANA KENTUCKY ALABAMA NEWMEXICO ALASKA MISSISSIPPI GEORGIA LOUISIANA ILLINOIS VIRGINIA SOUTHCAROLINA VERMONT WESTVIRGINIA TEXAS MICHIGAN MAINE WISCONSIN FLORIDA OHIO NEWHAMPSHIRE PENNSYLVANIA DELAWARE NEWYORK NORTHCAROLINA MASSACHUSETTS MARYLAND NEWJERSEY CONNECTICUT RHODEISLAND TENNESSEE 318.88 316.69 269.85 237.80 199.62 198.23 191.34 179.38 162.60 161.62 150.65 150.08 142.36 133.03 130.37 122.68 120.44 90.12 57.63 56.31 43.44 36.93 32.99 31.66 31.06 26.95 24.80 21.14 17.95 15.62 12.49 12.47 12.46 11.54 8.77 8.48 7.91 7.64 7.10 6.89 6.16 5.96 5.64 5.56 3.71 3.49 3.29 2.25 2.09 1.24 Note: Number of public hospitalization due to meth, normalized per 100,000 inhabitants. 31 TABLE 3 – SOCIO ECONOMIC CONTROLS DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS % White not Hispanics % White Hispanics % Black Hispanics % Black not Hispanics % Asian not Hispanics % Asian Hispanics % Indian Hispanics % Indian not Hispanics % Unemployment Income per capita People below the poverty line Number of Banks and Saving Institutions Percentage of poverty Number of Social Security Recipients Density Number of Pawnshops (1) Mean (2) Standard Deviation 0.818 0.0431 0.00195 0.106 0.0104 0.000425 0.00150 0.0185 5.158 25,341 13,919 41.39 0.141 19,074 350.8 6.339 0.168 0.0688 0.00477 0.153 0.0283 0.00146 0.00269 0.0601 1.968 6,458 40,443 30.45 0.137 42,203 2,436 7.462 32 TABLE 4 – DIFFERENCE IN DIFFERENCES Panel A - Baseline Treated*Post (1) Larceny (2) Burglary (3) M/V Theft (4) Arson (5) Murder (6) Assault (7) Rape (8) Robbery -0.0483 (0.0529) -0.0801 (0.0530) 0.0153 (0.0480) 0.109 (0.119) -0.121*** (0.0311) -0.0111 (0.0510) -0.0490 (0.0617) -0.179*** (0.0384) Panel B – Baseline + Sensitive Controls (Law Enforcement & Hospital Admissions for Other Addictions) Treated*Post -0.0162 (0.0480) -0.0684* (0.0356) -0.0179 (0.0384) 0.0722 (0.111) -0.123*** (0.0444) -0.00729 (0.0435) -0.0604 (0.0619) -0.149*** (0.0249) Panel C – Baseline + Sensitive Controls+ State Linear Trends Treated*Post -0.133*** (0.0392) -0.144*** (0.0527) -0.0685 (0.0449) -0.105 (0.0886) -0.0591 (0.0458) -0.0969* (0.0508) -0.00369 (0.0568) -0.143*** (0.0501) YEAR FE COUNTY FE Controls YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the state/year level. I use the xtivreg2 command in Stata. Each column represents a different regression, one for each type of crime. All the specifications in each panel include year FE, county FE and all county-varying observables. Panel A is the baseline diff-in-diff specification. In panel B I add controls that might be potential outcomes and, hence, confounding factors in the analysis. In Panel C I add State Linear Trends to Baseline and Sensitive Controls. 33 TABLE 5 - PRE TRENDS Lead7*Treated Lead6*Treated Lead5*Treated Lead4*Treated Lead3*Treated Lead2*Treated Lead1*Treated Treated*Post (1) Larceny (2) Burglary (3) Robbery (4) Murder -0.0167 (0.0269) 0.0396 (0.0424) 0.0889 (0.0567) 0.0618 (0.0652) 0.0695 (0.0657) 0.115 (0.0731) 0.114 (0.0788) -0.0165 (0.0295) 0.0455 (0.0410) 0.0670 (0.0546) 0.0292 (0.0822) 0.0492 (0.0889) 0.0922 (0.0886) 0.0857 (0.106) -0.162** (0.0638) -0.0762 (0.0845) -0.0783 (0.0585) -0.0786 (0.0627) -0.0802 (0.0587) -0.0520 (0.0617) -0.152 (0.0987) -0.120 (0.0876) -0.0903 (0.0722) -0.0347 (0.115) -0.131 (0.0948) -0.211*** (0.0561) -0.0480 (0.105) -0.157 (0.102) 0.0145 (0.0926) -0.0333 (0.104) -0.265*** (0.0834) -0.223** (0.108) Observations 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 Number of fips 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES COUNTY FE YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the state/year level. This table shows the analysis of the pre-trends only for the crimes affected by the change in the laws. I omit the interaction between the dummy for the year 1997 and the treated dummy. TABLE 6 – ANALYSIS AROUND THE LAWS’ THRESHOLD (2003 - 2006) Treated*Post (1) Larceny (2) Burglary -0.108*** (0.0319) -0.132*** (0.0425) (3) M/V Theft -0.0657* (0.0364) (4) Arson (5) Murder (6) Robbery (7) Assault (8) Rape 0.0203 (0.0913) -0.130*** (0.0472) -0.168*** (0.0525) -0.0889** (0.0359) -0.0356 (0.0633) Observations 5,398 5,398 5,398 5,398 5,398 5,398 5,398 Number of fips 1,384 1,384 1,384 1,384 1,384 1,384 1,384 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES COUNTY FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the state/year level. 5,398 1,384 YES YES ALL 34 TABLE 7 – DRUGS ARRESTS (1) Cocaine Treated*Post 0.0164 (0.0626) (2) (3) Sales Marijuan Synthetic a -0.00251 -0.166* (0.0132) (0.0971) (4) (5) Others Cocaine 0.0365 (0.146) -0.0193 (0.0725) (6) (7) Possession Marijuana Synthetic 0.0221 (0.0532) (8) Others -0.347*** (0.105) -0.00898 (0.0968) Observations 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 Number of fips 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES COUNTY FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the state/year level. 12,715 1,393 YES YES ALL TABLE 8 - FIRST STAGE (1) Crystal Meth Labs Treated*Post -0.435*** (0.0519) (Kleibergen-Paap Wald F statistic) 67.26 Observations 3,798 R-squared 0.259 YEAR FE YES STATE FE YES Controls ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the county level. TABLE 9A– OLS/IV PROPERTY CRIMES (1) (2) Larceny OLS IV Meth Labs 0.0555** (0.0152) * 0.203** (0.0693) * (3) (4) Burglary OLS IV 0.0447** (0.0133) * 0.291** (0.0851) * (5) (6) M/V Theft OLS IV 0.0482** (0.0167) * 0.151 (0.0995) (7) (8) Arson OLS IV 0.0317 (0.0223) -0.142 (0.148) Observations 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES STATE FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the county level. 3,798 YES YES ALL 35 TABLE 9B – OLS/IV VIOLENT CRIMES (1) (2) Robbery OLS IV Meth Labs 0.0802*** (0.0245) 0.271* (0.159) (3) (4) Murder OLS IV 0.0474*** (0.0180) (5) (6) (7) (8) Assault OLS IV Rape 0.235 (0.165) OLS IV 0.0316 (0.0219) -0.118 (0.139) 0.0481*** (0.0162) 0.0807 (0.0897) Observations 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 3,798 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES STATE FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the county level. TABLE 10 – TRIPLE DIFFERENCE IN DIFFERENCES (DISTANCE FROM MEXICO) Dist. Mexico*Post*Treated (1) Larceny (2) Burglary (3) Murder (4) Robbery -0.08* (0.04) -0.07*** (0.02) 0.32 (0.23) -0.19 (0.18) Observations 12,715 12,715 12,715 12,715 Number of fips 1,393 1,393 1,393 1,393 YEAR FE YES YES YES YES COUNTY FE YES YES YES YES Controls ALL ALL ALL ALL Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the State/Year level. 36 TABLE 11 - HATE CRIMES BY TYPE OF BIAS - UNITES STATES 1997-2010 Bias Number of Episodes Percentage Anti-White Anti-Black Anti-American Indian Anti-Asian Anti-Multi-Racial Anti-Jewish Anti-Catholic Anti-Protestant Anti-Islamic Anti-Other Anti-Multi-Religious Anti-Atheism/Agnosticism Anti-Hispanic Anti-Other Ethnicity Anti-Male Homosexual Anti-Female Homosexual Anti-Homosexual (both) Anti-Heterosexual Anti-Bisexual Anti-Physical Disability Anti-Mental Disability 10,184 36,190 800 3,032 2,707 11,903 745 672 1,721 1,765 573 76 6,978 6,279 10,086 2,277 3,126 269 252 240 400 10.16 36.09 0.8 3.02 2.7 11.87 0.74 0.67 1.72 1.76 0.57 0.08 6.96 6.26 10.06 2.27 3.12 0.27 0.25 0.24 0.4 Number of Episodes 100,275 37 TABLE 12 – HATE CRIMES BY TYPE OF OFFENSE – UNITED STATES 1997 - 2010 UCR CODE Type of Offense Episodes Percentage 09A 09B 100 11A 11B 11C 11D 120 13A 13B 13C 200 210 220 23A 23B 23C 23D 23E 23F 23G 23H 240 250 26A 26B 26C 26E 270 280 290 35A 35B 36A 36B 370 40A 520 Murder/non-negligent manslaughter Negligent manslaughter Kidnapping/abduction Forcible rape Forcible sodomy Sex assault Forcible fondling w/object Robbery Aggravated assault Simple assault Intimidation Arson Extort/blackmail Burg/B & Pocket-picking Purse-snatching Shoplifting Theft Theft from building Theft from coin-op machine Theft of motor vehicle All other mv parts Motor vehicle larceny Counterfeit/forgery theft FALSE pretenses/swindle Credit card/ATM game Impersonation fraud Wire fraud Embezzlement Stolen property Destruct/vandalism Drug/Narc violations offenses Drug equip Incest Statutory rape violations Pornography/obscene material Prostitution Weapon law violations 122 1 45 82 29 9 53 1,661 10,599 18,776 30,630 573 20 1,678 9 12 192 245 7 288 92 1,125 176 85 110 44 25 5 23 43 33,109 229 27 6 4 13 10 118 0.12 0 0.04 0.08 0.03 0.01 0.05 1.66 10.57 18.72 30.55 0.57 0.02 1.67 0.01 0.01 0.19 0.24 0.01 0.29 0.09 1.12 0.18 0.08 0.11 0.04 0.02 0 0.02 0.04 33.02 0.23 0.03 0.01 0 0.01 0.01 0.12 100,275 100 Total 38 TABLE 13 – HATE CRIMES Panel A - Baseline Treated*Post (1) Total Hate Crimes (2) Anti-White (3) Anti-Black (4) Anti-Jewish (5) Anti-Islamic (6) AntiHomosexual (7) AntiHeterosexual (8) Anti-Physical Disability 0.0843 (0.188) -0.0907 (0.135) -0.00 (0.0403) 0.0336 (0.0218) 0.00865 (0.0113) 0.0443*** (0.0130) 0.00833 (0.00551) -0.0158 (0.0176) 0.206*** (0.0755) 0.0120 (0.102) -0.0446 (0.102) 0.0546 (0.0344) 0.0252* (0.0148) 0.0582*** (0.0216) 0.0188*** (0.00509) -0.0135 (0.0196) Panel B – Baseline + State Trends Treated*Post Panel C – Baseline + State Trends Log Linear Specification Treated*Post 0.0415 (0.0419) -0.0182 (0.0271) -0.00593 (0.0342) 0.0212 (0.0185) 0.00880 (0.00593) 0.0271*** (0.00742) 0.00819*** (0.00129) -0.00182 (0.00775) YEAR FE COUNTY FE Controls YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL YES YES ALL *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Standard errors are double clustered at the State/year level. 39 Figures 40 41 42 43 44