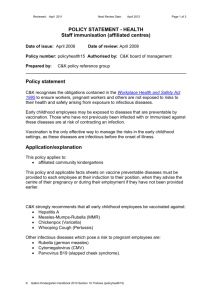

National Immunisation Strategy 2013-2018

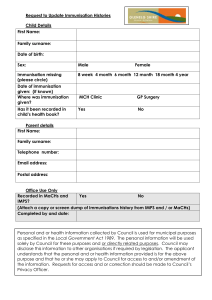

advertisement