Measurement Synthesis Paper - Josh Rendall

advertisement

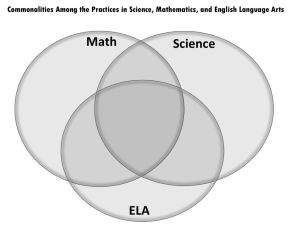

Josh Rendall 2/26/13 EDCI 534 Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? The Standard The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) has created standards and expectations that serve as the guidelines of what is important in the realm of teaching and learning mathematics. Of course there are the obvious topics of algebra, geometry, and probability, among numerous others, that most people would recognize because secondary school classes are dedicated to them. In addition, there is so much publicity about algebra specifically because of standardized tests and the fact that it is considered a gateway for high school graduation. However, there is another standard that may not be easily recognized by most people when they think of mathematics: Measurement (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2013). Students, as they journey through school from kindergarten to the 12th grade, should be able to meet certain expectations in the measurement standard. According to NCTM, one of the overall goals of this standard is to “understand measurable attributes of objects and the unit, systems, and processes of measurement” (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2013). Specifically, students in elementary grades should begin to understand how to measure standard units and select an appropriate tool and unit when measuring an object. Students also should be able to approximate measurements and perform simple unit conversions, such as feet to inches. As students move into middle school, NCTM’s standards progress not just to knowing both the metric and customary systems of Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 2 measurement, but students should be able to easily convert between units within the same system. Students also begin to look at measuring angles, perimeter, areas, surface area, and volume. Finally, high school students should be able to problem solve and think critically when looking at different scenarios that incorporate measurement to them. The second overall goal of NCTM’s measurement standard is to “apply appropriate techniques, tools, and formulas to determine measurements” (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2013). In the elementary years, students are expected to learn how repeat the length of a smaller unit to measure a larger unit and select and apply the standard units of measurements to objects. This could be done with something small like a paper clip and figuring how long a piece of paper is in terms of the length of one paper clip. Middle school students should be able to apply and develop formulas for areas of different polygons and volumes and surface area formulas to prisms, pyramids, and cylinders. Scale factors, in concurrence with ratios and proportions, also are learned during middle school years where more higher-level thinking about math begins to take place. Finally, high school students are expected to be able to find approximate error and analyze how precise measurements are. Students should also be able to understand more abstract objects (cones, spheres, etc.) and how to find their volumes and measurements. The new Common Core Mathematics Standards students will be subjected to in the near future emulate what NCTM says. The measurement standards are completed mainly by 5th Grade in terms learning what the standard units of measurement are and recognizing how to solve problems with measurement. The Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 3 terminology of length, area, volume, and mass are all supposed to be taught in the elementary years, along with the conversions between units of measurement within the same system (Common Core Standards Writing Team, 2012). Students then work on apply measurement to more complex ideas, such as ratios and proportions, in middle school and move away from only physically looking at measurement. There is more abstraction and problem solving involved. In high school, much of the focus of the Common Core looks at probability and calculating expected values using the measurement knowledge that has been learned in prior grade levels (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2012). These standards from NCTM and the Common Core are vast. They are taught from when a student begins in elementary school until he or she graduates from high school. Multiple facets of measurement need to be taught – area, length, volume, surface area, mass, boundaries, and perimeter. The list grows and grows. It has to be a group effort from all teachers from all grade levels in order for a student to succeed in the measurement standard. That being said, it would be naïve to think that every standard of measurement could be synthesized and analyzed together. There is just too much information and research to try and do that. Instead, the focus of this paper will look at topics that occur more during the middle school years. What does the research say about what is happening to students during their 6th – 8th grade years concerning the measurement standard? What can be improved to help students meet the standards and expectations NCTM and the Common Core have made? Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 4 The Struggle Measurement is the topic of mathematics that all students, not just middle school, seem to have the most trouble with during the course of their math education. It is often not given enough attention in textbooks, in schools, and by teachers (Lewis & Schad, 2006). At times, it could be considered forgotten among all of the other parts of mathematics that are taught (Foley, 2010). When teachers themselves were asked, they overwhelming said that measurement is the section where their middle school students are the weakest. It is also interesting to note that these same teachers, along with other adults, view measurement as the most applicable to a student’s life (Preston & Thompson, 2004). Every student will be affected by measurement during their life, whether it is dealing with a car, measuring furniture for a room, or cooking in the kitchen. The same probably cannot be said about the other subjects in mathematics. Students consistently perform low on standardized testing, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, in measurement, where the topic of length is a struggle even though it is taught beginning in kindergarten (Kamii, 2006). Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) also show that U.S. students’ performance on measurement problems were significantly lower than in other math categories (Driscoll, 2007). The question then becomes - Why is measurement so hard for students? One overlying factor in why students struggle learning measurement is how it is taught currently in schools today. Students like procedures. They make sense, Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 5 do not require much thinking, and can produce the correct answer. Mathematics in general could be viewed in this light. It should not be a surprise, then, that measurement is often taught as a procedure. However, because of this, students have no actual concept of what they are really looking at (Gray, 2001). For example, students will just memorize how to convert from one unit to another, without really understanding what they are doing or why they are doing it. Often, when converting units, students do not know when to multiply or divide. They are “not able to visualize the problem or [do] not have efficient strategies for solving the problems” (Klamik, 2006, p. 188). Everything a student focuses on is just memorizing the procedure, insteading of being able to understand what the measurements physically mean. Along with the prodecural nature of measurements, students do not see the value of it outside of the classroom walls. To a student, measurement can be as simple as finding one unit of measurement, following an empirical procedure, and writing a numeric answer. Rarely are students asked to think logically about measurement. They are not even asked to compare two objects, via their measurements, in most classrooms (Kamii, 2006). It is a procedure of finding a measurement and writing it down. In learning length, for example, students are often given a pages with objects where a ruler is already drawn out for them (Martinie, 2004). There is no real world application or high level thinking involved for students to see the value of measurement. Perhaps the biggest struggle students have with measurement, espeically in the United States, is the fact that there are two entirely different systems to learn – Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 6 metric and customary. Currently, the United States is one of a handful of countries still using the customary system (Monroe & Nelson, 2000). The rest of the world has adopted the metric system. Because of this, students are bombarded with units, from meter to inch to liter to ounce to pound – the list goes on and on. There is so much information and different units of measurement for students to keep track of, and not only do they have to keep track of it, the two systems of measurement do not correlate well together (Preston & Thompson, 2004). It is clear that some of the struggles students have about measurement stems from the fact that two systems are taught simultaneously. Another important observation about the two systems is the amount of time spent in a classroom on them. Often, there is a week’s (sometimes longer) worth of lessons dedicated to the customary system, whereas only a few days focused on the metric system (Taylor, Simms, Kim, & Reys, 2001). It is important to note that students in the United States perform better on items using the metric system rather than the customary system (Preston & Thompson, 2004). However, they are lagging behind significantly internationally and still have a difficult time learning measurement. The Change The research about the measurement standard is clear – students are not getting it! What then can be done to improve it? There is not a single, one size fits all solution to this dilemma. It will require a revamp in how educators teach measurement and how students view it. There is an inexhaustible list of plans and ideas of how to improve students’ comprehension of measurement. For the purpose of this paper, only a few can be highlighted. The ideas featured were chosen because Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 7 of how they correlate to the struggles and challenges students face currently in the classroom when learning measurement. When it comes to the classroom lessons, most research says teachers should look at changing how measurement is taught. Lessons cannot be just memorizing facts and procedures. Instead, students should learn through practice and problem solving. Rather than just having students work on unit conversion over and over, students could create their own word problems. These could then be exchanged between students and solved (Klamik, 2006). It allows the students to take onwership of what they are learning and make their lesson unique to their interests. This is just a small example of the problem solving type questions and lessons that could be implemented into the classroom. Middle school students, especially, are missing out on the problem solving nature of measurement (Driscoll, 2007). Instead, they are learning formulas and memorizing the information; there is little meaning to what they are learning. In order to help these students improve their comprehension of measurement, a change is the classroom is clearly necessary. Relating measurement to other parts of mathematics and the real world is another way to help students improve. Measurement is not a single, isolated topic. It can be integrated into all the other parts of mathematics in some way. It makes measurement more accessible and meaning to the student (Martinie, 2004). Relating measurement to other parts of mathematics is important because time is at a premium in a classroom. There is not enough time to add more lessons to a school calendar (Preston & Thompson, 2004). A teacher needs to find ways to incorporate Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 8 this into their other lessons. Even an algebra lesson can have measurement interwoven into it (Foley, 2010). Relating measurement to the other strands of mathematics is not enough to improve student performance, though. Problems that are applicable to the real world are essential for students to truly understand measurement. The subject becomes tangible to students, and they can begin to understand that measurement occurs everywhere (Pumala & Klabunde, 2005). They can also begin to see the value of knowing measurement in their lives after graduation. Sometimes, estimates of measurement can be used in the classroom. It show they can understand mentally what units represent and the relationships among them without being bogged down in the number calculations (Preston & Thompson, 2004). If teachers are going to change how they teach their measurement lessons, assessment changes may also be needed. A traditional test at the end of the unit where students are asked mundane, lower-level thinking questions is not appropriate for checking student comprehension. Instead, “formative assessment, continual feedback, and tracking of progress” (Pumala & Klabunde, 2005, p. 453) should be used. Journal entries, group work, open-ended questions, and problem solving activities should be integral pieces to a measurement curriculum. Students should find their own measurements empirically and actually experience visually what they are measuring (Kamii, 2006). It will be messy to teach in this style. Students will resist the open-ended questions and the lack of guidance from the teacher (Foley, 2010). However, it is a necessary change if educators are going to help students improve in the standard of measurement. Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 9 The metric system is an important key to success for students when it comes to mastering measurement. NCTM (2006) has the following position statement about teaching measurement: To equip students to deal with diverse situations in science and other subject areas, and to prepare them for life in a global society, schools should provide students with rich experiences in working with both the metric and the customary systems of measurement while developing their ability to solve problems in either system. NCTM understands that students cannot just learn the customary system, which is commonplace in the United States. The metric system must be learned as well. Students need to see the relationships and estimate conversions between the two systems. Teachers also need to work to incorporate the metric system more (Taylor, Simms, Kim, & Reys, 2001). The habit of teachers is to only look at the customary system, but there needs to be a larger focus on implementing the metric system in the math classroom. It would be difficult for United States to make a complete switch to the metric system because of the engrained nature that the customary system has in the country. It would also be difficult and costly for many businesses to make the switch (Monroe & Nelson, 2000). The world is getting smaller and smaller because of technology and increased means of communication. The United States’ economy is international, and for businesses to be successful, the metric system must be used (Taylor, Simms, Kim, & Reys, 2001). Because of this, students need to be adequately prepared in school to meet the world and the metric system. Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 10 Conclusion Measurement is one of the fundamental building blocks of mathematics. Its importance is being overlooked compared to some of its counterparts – algebra, probability, and geometry. It cannot be overlooked anymore. Measurement cannot be viewed as the last section in the book that is only covered if there is extra time. It cannot just be a few lessons of unit conversions where students are not required to think and just perform procedures. It needs to be problem solving and hand’s-on activities where students can begin to actually comprehend how measurement works, see it visually, and effectively use the tools necessary to find measurements. Measurement should not just be a bunch of number crunching, but a mixture of lessons where students can do everything from figuring out the width of a fingernail to estimating the mass of the earth. Students need to understand the intricacies of measurement to be ready for the world around them. Measurement is a part of everyday life. Students need to see the value in learning and comprehending it. If the purpose of school is to prepare students for the real world and life after graduation, measurement needs to have a larger focus in the math classroom. Students deserve it, and they need teachers who are willing to take the risk and incorporate all forms of measurement, metric and customary, into the classroom. Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 11 References Common Core Standards Writing Team. (2012, June 23). Progressions Documents for the Common Core Math Standards. Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2012). Mathematics - Content Measurement and Data. Retrieved from Common Core State Standards Initiative: http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Content/MD Driscoll, M. (2007). Fostering Geometric Thinking: A Guide for Teachers, Grades 5 - 10. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Foley, G. D. (2010, September). Measurement: The Forgotten Standard. The Mathematics Teacher, 104(2), 90-91. Gray, E. D. (2001). Teaching Measurement in the 21st Century. Louisiana Association of Teachers of Mathematics Journal, 2(1). Louisiana. Retrieved from Louisiana Association of Teachers of Mathematics: http://www.lamath.org/journal/Vol2/gray.pdf Kamii, C. (2006, October). Measurement of Length: How Can We Teach It Better? Teaching Children Mathematics, 13(3), 154-158. Klamik, A. (2006, October). Converting Customary Units: Multiply or Divide? Teaching Children Mathematics, 13(3), 188-191. Lewis, C., & Schad, B. (2006, October). Teaching and Learning Measurement. Teaching Children Mathematics, 13(3), 131. Martinie, S. (2004, April). Families Ask: Measurement: What's the Big Idea? Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 9(8), 430-431. Measurement: What’s the Big Struggle? 12 Monroe, E. E., & Nelson, M. N. (2000, October). Say "Yes" to Metric Measure. Science and Children, 38(2), 20-23. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2006). Teaching the Metric System for America's Future. Retrieved from National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: http://www.nctm.org/about/content.aspx?id=6346 National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2013). Measurement Standard. Retrieved from National Council of Teachers of Mathematics: http://www.nctm.org/standards/content.aspx?id=316 Preston, R., & Thompson, T. (2004, April). Integrating Measurement across the Curriculum. Mathematics Teaching in the MIddle School, 9(8), 436-441. Pumala, V. A., & Klabunde, D. A. (2005, May). Learning Measurements through Practice. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 10(9), 452-460. Taylor, P. M., Simms, K., Kim, O.-K., & Reys, R. E. (2001, January). Do Your Students Measure Up Metrically? Teaching Children Mathematics, 7(5), 282-287.