The Monitor - Issue 3, December 2014

advertisement

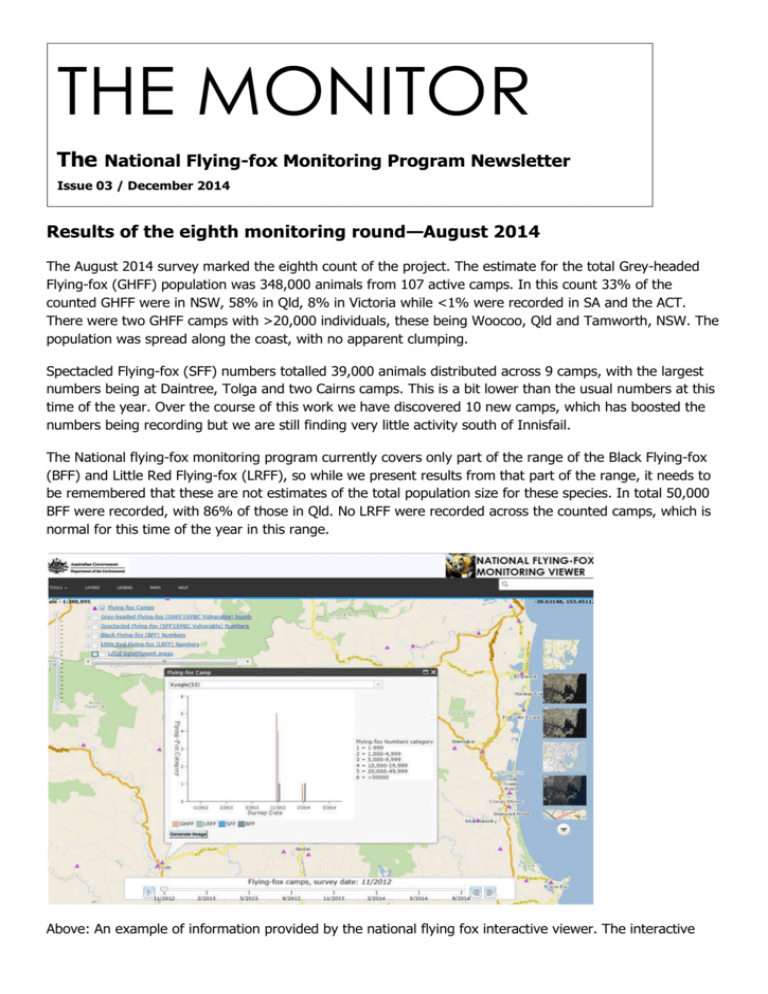

THE MONITOR The National Flying-fox Monitoring Program Newsletter Issue 03 / December 2014 Results of the eighth monitoring round—August 2014 The August 2014 survey marked the eighth count of the project. The estimate for the total Grey-headed Flying-fox (GHFF) population was 348,000 animals from 107 active camps. In this count 33% of the counted GHFF were in NSW, 58% in Qld, 8% in Victoria while <1% were recorded in SA and the ACT. There were two GHFF camps with >20,000 individuals, these being Woocoo, Qld and Tamworth, NSW. The population was spread along the coast, with no apparent clumping. Spectacled Flying-fox (SFF) numbers totalled 39,000 animals distributed across 9 camps, with the largest numbers being at Daintree, Tolga and two Cairns camps. This is a bit lower than the usual numbers at this time of the year. Over the course of this work we have discovered 10 new camps, which has boosted the numbers being recording but we are still finding very little activity south of Innisfail. The National flying-fox monitoring program currently covers only part of the range of the Black Flying-fox (BFF) and Little Red Flying-fox (LRFF), so while we present results from that part of the range, it needs to be remembered that these are not estimates of the total population size for these species. In total 50,000 BFF were recorded, with 86% of those in Qld. No LRFF were recorded across the counted camps, which is normal for this time of the year in this range. Above: An example of information provided by the national flying fox interactive viewer. The interactive viewer allows you to explore flying fox camps monitored as part of the program along with their status, species and size. If you know of camps that are not shown on this viewer please contact us at species.policy@environment.gov.au A map of the camps covered in the NFFMP surveys can now be viewed at www.environment.gov.au/node/16393. When on the website, clicking on a camp icon will show a plot of species composition and numbers recorded at that camp during NFFMP surveys. Where were the flying-foxes in August? The heat maps above show the distribution of the different flying-fox species across the region of the National Flying-fox Monitoring Program—the darker the colour the greater the abundance of flying-foxes in an area. Red triangles represent visited camps. Readers are reminded that the numbers are outlined above only to get a sense of the outcome of the count and it must be noted that, at this point in time, they are indicative only. The researchers are still in the process of refining analysis methods and estimating some errors. As a consequence it is not yet possible to say what level of confidence can be assigned to the estimate. Describing the errors is a focus of the monitoring programme’s ongoing research. The aim of the programme is to establish a reliable baseline estimate of the flying fox populations in 2013 and over time to estimate trends. This will take a number of years since each quarterly count will be subject to various factors which will influence the results, making assessment of population size more difficult. 2 The National Flying-fox Monitoring Programme is collaboration between the Australian Government, the South Australian, Victorian, New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory and Queensland governments, CSIRO, local governments and volunteers. Monitoring adventures in the Tweed The National Flying-fox Monitoring Program is a collaboration between the Australian Government, South Australian, Victorian, New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory and Queensland governments, the CSIRO, local governments and volunteers. In New South Wales and Queensland, quarterly surveys are carried out by agency staff, local government staff and volunteers. A great deal of the program’s success in these states is due to the support and dedication of these groups and individuals. To get a better idea of the contribution made by these groups, The Monitor spoke to David Hannah and Marama Hopkins of the Tweed Shire Council in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales. The Monitor (TM): The Tweed Shire Council is a regular participant in the monitoring program. So when the quarterly surveys are conducted, who in your team is usually involved? David Hannah (DH): Well, as the Council’s Senior Environmental Scientist I’m usually involved. Marama—in her capacity as Biodiversity Planning Officer—is also a regular. The other council staff members who regularly participate in the flying fox counts include my fellow environmental scientist Sally Cooper, Biodiversity Planning Officer Michael Banks, Pam Gray, Scott Hetherington, Mick Healey and Cheyne Warren. TM: How many camps do you usually monitor during each survey? DH: The council monitors up to seven camps, depending on staff availability and camp occupancy. TM: Where are the camps usually found? What type of terrain do you have to go through to reach them? Marama Hopkins (MH): The camps are mostly located among mangroves, rainforest, rivers and estuaries. TM: I imagine that makes it challenging for the council to conduct the surveys? What special equipment or techniques do you use to deal with these challenges? MH: Most camps can be reached on foot with the exception of camps located on islands within Terranora Broadwater. For this site, a kayak is used to access the camp—which can be somewhat perilous when things don’t go to plan! [laughs] TM: Sounds interesting, even entertaining. Would you mind sharing a couple of these stories with us? DH: You can say that there have been a number of “mishaps” during some of the counts within the 3 Terranora Broadwater. But not to worry, there were no serious injuries—except maybe for the ego of one particular counter who will remain unnamed. Both incidents that quickly come to mind involved the same counter. There was the time that colleague of ours stepped off the kayak, only to momentarily disappear underwater before exclaiming that the sand bank didn’t look that deep! MH: Then there was the time that the same counter and another colleague of ours overturned the kayak while negotiating a landing. Needless to say, most of us take extra care when taking on the Terranora count with that individual. TM: Kayaking misadventures aside, what other interesting stories or observations can you share with us about the monitoring program? MH: It has been interesting to observe the changes in distribution and composition of the flying-fox camps over time. For example, in general animals at the Bray Park camp are more or less evenly distributed throughout the wetland—with black flying-foxes at one end, and grey-headed flying-foxes on the other. At last count however, grey-headed flying-foxes were very densely concentrated in the centre of the camp, with the black flying-foxes scattered around the edges. There was no obvious reason for this change in species distribution within the camp. TM: Why do you think it is important to monitor flying-fox populations? MH: The information gathered on camp locations, numbers and fidelity to sites within the Tweed Shire is providing a valuable resource for the council. This information will allow for better informed decision-making in relation to the assessment of the impacts of developments adjacent to camps. In the long term, it is hoped that the monitoring will provide some insight into seasonal patterns of camp occupancy and camp site selection in the Tweed. TM: Other than participating in the monitoring program, does the council carry out any other flying-foxrelated surveys or research? And is it home to any other significant bat roosts/species? DH: The council carries out a range of threatened species management activities as part of our biodiversity management program, such the monitoring of the eastern blossom bat (Syconycteris australis) at Koala Beach Estate. Koala Beach Estate is a residential subdivision in the shire. The initial surveys for the Fauna Impact Statement in the mid-1990s, found that blossom bats occured within the estate. At that time, it was suggested that the estate, while not supporting a resident population of the blossom bat, was a major food resource for the species, particularly during winter months. After that, an area of habitat of Coast Banksia-dominated forest—that was around 1.2 hectares in size— was reserved as part of the final subdivision approval. Since 2007, the council has been carrying out regular population monitoring, as well as habitat management activities, to ensure that housing developments and associated disturbance are not stopping the population from using the Coast Banksia as a major feeding ground. The heat is on: Flying-foxes and extreme heat events 4 With the heat of the summer months almost upon us, it is a good time to look into the effects of heatwaves on flying-fox colonies. The Monitor got in touch with animal ecologist Dr Justin Welbergen from the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at the University of Western Sydney to discuss the work he has been doing in this area over the last 12 years. The Monitor (TM): Congratulations on your research. It looks into an area that is of great interest to our readers so thank you for speaking with us. Dr Justin Welbergen (JW): Thank you, it’s my pleasure. TM: Can you briefly tell us about the objectives of your research on flying-foxes and heat stress events? The primary objective of our ongoing research is to understand how extreme heat events affect flyingfoxes, in the present as well as in the future. Our research has shown that temperatures beyond a threshold of 42° C cause wide-spread mortality in flying-foxes (‘die-offs’), and this is an issue that is likely to become increasingly important for flying-foxes and other organisms under climate change. As flying-fox die-offs are particularly conspicuous events, this raises concern that similar impacts happen in species with more solitary and cryptic lifestyles. In addition, flying-foxes reflect the health of the ecosystems in which they occur because they are important pollinators and seed dispersers for a number of ecologically and economically-important plants. Extreme heat events are set to escalate further under climate change, and so our research into the vulnerability of flying-foxes to such events has implications for our understanding of the future of Australia’s biodiversity more broadly. TM: The range of the black flying-fox has extended approximately 600 km southwards in the past three decades. Do you think that more regular or more intense heat stress events in the future might see a northward range contraction, back towards the tropics? JW: This is a distinct possibility, and one of the issues we are investigating at the moment. As a general rule, Australian heat events are actually more extreme the further away they occur from the tropics. As black flyingfoxes have been expanding their range southwards, they are becoming increasingly exposed to maximum temperatures that are lethal to them. Climate change is expected to increase the species’ exposure to such temperature events even further, perhaps to the point where southern parts of the population are no longer sustainable and the species will contract back to less-extreme, more tropical latitudes. TM: Hybridisation and competition with the black flying-fox has been identified as a potential threat to the EPBC Act-listed grey-headed flying-fox. What are your thoughts on the interaction between the species and the potential effects of range shifts over time? JW: I think the jury is still out with respect to the impact that the black flying-fox has on the grey-headed flying-fox. However, where they co-occur, these two species clearly make use of the same roosting and foraging sites, and where individuals come into contact, black flying-foxes almost always seem to have the upper hand. There is ample circumstantial evidence that suggests that black flying-foxes may be having a negative impact on the species, but further research is clearly needed here. TM: The urban heat island effect is a well-documented phenomenon. Considering that many flying-fox camps occur in urban or peri-urban areas, is this likely to exacerbate the impacts of heatwaves? 5 JW: Indeed, the urban heat island effect is likely to exacerbate the impact of extreme heat events on flyingfoxes. Temperatures tend to be higher in cities during heatwaves due to the urban heat island effect, but in addition, the difference between urban and rural temperatures is also greater during heatwaves than at other times. This implies serious heat-related health risks facing urban flying-foxes in the twenty-first century. TM: There are now a number of permanent grey-headed flying-fox camps established at higher altitude than those on the coast (for example—Wagga Wagga, Tumut and Canberra). Do you think that this could be a response to changes in temperature patterns in other parts of the species’ range? JW: It is unlikely that flying-foxes have moved to these new locations to seek shelter from extreme heat because these places are also further west where summer temperatures are higher. For example, the maximum recorded temperature in Wagga Wagga is 45.2° C; for Tumut it is 44.0° C; and for Canberra it is 42.2° C—all above the 42° C where flying-fox death starts to happen. Instead it seems that flying-foxes temporarily seek out new locations during food shortages, and this sometimes leads to the establishment of new camps—such as during the critical food bottleneck in 2010 when several new western camps were formed. TM: Climatic changes are also likely to affect the flowering and fruiting patterns of native plants that flyingfoxes rely on for food. What effect do you think this might have, particularly in relation to critical food bottlenecks? JW: The effects of climate change on food availability are notoriously difficult to predict. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that extreme heat events have very negative impacts on food availability for flying-foxes. As extreme heat events will become more frequent and widespread under climate change, this implies that food bottlenecks will become more common for flying-foxes. TM: What kind of actions would you suggest communities or government agencies take to help make camps more resilient to heat stress events? JW: It is important to make sure that flying-fox camps provide ample shelter from extreme heat. We know that during extreme heat events, flying-foxes seek out the coolest places in the roost and the coolest places are found at the base of big trees or areas with dense understory. It is important not to disturb flying-foxes during an extreme-heat event as it may force them to leave such sheltered microclimates and so cause the animals to die from increased exposure. Promoting big trees and understory will directly make individual camps more resilient to extreme heat events. Some communities and government agencies use water to cool down flying-fox camps during extreme heat events. However, these actions may disturb the flying-foxes or and can potentially increase heat stress by artificially increasing humidity. That’s why controlled experiments are needed to show that, on balance, these actions are indeed beneficial for flying-foxes. Arguably, however, the most important way for increasing the resilience of flying-foxes to extreme heat events is by reducing the impacts of other stressors that affect the species, especially the harassment and destruction of roosts, and licenced killing at orchards. Who to contact: ACT: Murray Evans (02) 6207 2118 6 NSW: Stephen van der Mark (02) 9995 6710 QLD: Katrina Prior (07) 3330 5373 SA: Angela Duffy (08) 8463 4819 VIC: Tegan Brown (03) 9450 8759 CSIRO: Adam McKeown (07) 4059 5009 Australian Peter Wright Government: (02) 6274 1052 7