Origins Manual Chapter 1

advertisement

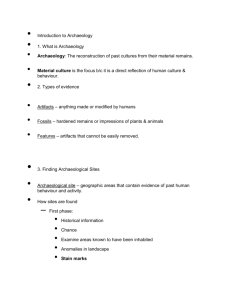

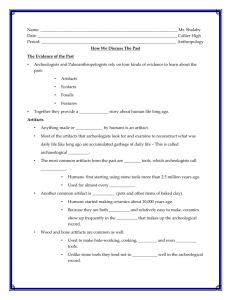

Chapter 1 Historiography: Taking a Good Look at History “How can we think objectively and historically about the events of the past?” This roots the course in an anthropological and archaeological perspective. This unit deals with the questions of perspective and point of view, bias, as well as the scientific method. 1-2 History as Interpretation 3-4 Historiography 5- 6 Avoiding Bias 7-8 Criteria for Judging and Examples of Good Theories 9 Archaeology’s Role in Interpreting History 10-13 Sources 14 Video viewing guide 15 Sources Consulted Essential Question: What is really real and how do we determine it Introduction Purposes Historians try to explain connections between the past and the present. They study how places looked in the past, how places and patterns of human activity have changed over time, and how geographic forces have influenced these changes. As you study history, you acquire an orientation to time; as you study archaeology, you acquire an orientation to space. Archaeologists, then, organize their thoughts with respect to spatial arrangements and distributions over the earth’s surface. Historians, on the other hand, organize their ideas with respect to time. Historians know well that events occur in places. Events, like people are distributed across the earth. All definitions of history's utility, however, rely on two fundamental facts. In the first place, history offers a storehouse of information about how people and societies behave. Consequently, history must serve, however imperfectly, as our laboratory, and data from the past must serve as our most vital evidence in the unavoidable quest to figure out why our complex species behaves as it does in societal settings. History offers the only extensive evidential base for the contemplation and analysis of how societies function, and people need to have some sense of how societies function simply to run their own lives. History tells the life stories of people who lived long ago and helps us learn about our common heritage as human beings. Studying past cultures helps us understand how our own culture has developed, making us who we are today. The second reason is history is inescapable; the past causes the present, and so the future. Any time we try to know why something happened—whether a shift in political party dominance in the American Congress, a major change in the teenage suicide rate, or a war in the Middle East—we have to look for factors that took shape earlier. Only through studying history can we grasp how things change; only through history can we begin to comprehend the factors that cause change; and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or a society persist despite change. History tells the life stories of people who lived long ago and helps us learn about our common heritage as human beings. Studying past cultures helps us understand how our own culture has developed, making us who we are today. Is History True? History as Interpretation The earliest audience for history consisted simply of people who liked a good story. The appeal of history for many was that it brought to life real people and events. History was also considered important because it could explain- without the moral teachings- how or why things turned out as they did. It could show how a war happened, why one side won, and what the results were. By studying the past, people could learn what mistakes to avoid and what good examples to follow. According to Edwin Fenton, this is not an easy task for six basic reasons. 1 Knowledge of the past is incomplete We probably know only a fraction of one percent of what has happened in the past. Just think of all the things we do not know. We have few accurate statistics on population or trade or government income. We know next to nothing about the lives of individuals. Most of what happened was never recorded. Records can be lost or destroyed History cannot be a complete record of what happened; at best it can be a record only of those events that were recorded in a form that has come down to us. The Great Library of Alexandria was lost; writings of Aristotle are missing; weather, fire, water and time itself have erased much of the past. Bias is We do not know whether or not the documents we do have contain information that present is accurately representative of the events that took place. Because most documents because of the were written by men who were better educated and more intelligent than the average, authors is it likely that the records we have reflect disproportionally the point of view of the educated upper class. Cannot learn everything about an event or period. Must select from available material. Presentation 2 Let us suppose that a scholar set out to read, in the original language, all remaining source material about the Pyramid of Giza and to supplement this knowledge by examining buildings and other artifacts from the period. He would have to become an accomplished linguist to read the inscriptions, then, he would need to be a paleobotanist, architect, specialist in ancient materials used for mummification and more. No one person could read and see everything in one lifetime. Even Dr. Zawi Hawass, renowned Egyptologist, relies on experts in various fields when working on an excavation It would be absurd if historians just listed in chronological order all the facts they discovered. We would be bored to death if we read such a compilation. A historian could not even take down notes on all the material researched. She would be forced to select information to note on her cards, just as students doing research in the library note down some things and omit others. But as soon as the historian makes a note of one event and decides not to make note of another, she interprets. She says, in effect, “This fact is important, and the other one is not.” But how does she know what is important, what is worth noting down? She already has in mind an interpretation of history in order to make this decision. Whether the historian is correct is beside the point. What is significant to us is that she has interpreted in the very process of taking notes. If she selects, she does so with some principles in mind. As soon as she has established principles of what is important, she interprets. A historian interprets not only by selecting certain material, but also by presenting it in a certain way. The type of print, photos, language of an article can deliver an impression that may or may not be true. Historiography Historiography is writing of history based on a critical analysis, evaluation, and selection of authentic source materials and composition of those materials into a narrative subject to scholarly methods of criticism. When doing history, it helps to keep in mind that there are many different ways of determining how history happens. The following list of selected historians can give you some ideas of how the great historians "did" history. Plutarch: His thesis is that the very character of men changes history. All great men have an impact on their time either for good or ill. Please note that great does not equal good. Hitler was a “great” man, but not a good one. Great men move history. Toynbee: Toynbee's theory is that all civilizations are faced with crises, which are either of ideas or of technology. How the civilization responds determines whether it will survive. If a new idea enters a culture, then it must adapt to that idea or reject it. The same applies to new technology. Darwin: While not a historian, Darwin’s biological application in Origin of Species noted that complex creatures evolve from more simplistic ancestors naturally over time. As random genetic mutations occur within an organism's genetic code, the beneficial mutations are preserved because they aid survival -- a process known as "natural selection." The "fittest" individuals could be considered those that are ideally suited to a particular environment. This theory has been applied to cultures, government and economics. History Malthus Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) contains Malthus's observation that in nature plants and animals produce far more offspring than can survive, and that Man too is capable of overproducing if left unchecked. Malthus was a political economist who was concerned about the decline of living conditions in nineteenth century England, which he blamed on three elements: the overproduction of young; the inability of resources to keep up with the rising human population; and the irresponsibility of the lower classes. To combat this, Malthus suggested the family size of the lower class ought to be regulated such that poor families do not produce more children than they can support. War and disease could also help reduce the lower classes. Marx--Material Dialectic. Marx used Hegel's ideas of thesis, anti-thesis and synthesis, and applied them to classes of people throughout history. Any ruling class controlled the "means of production" which gave them wealth and power to rule. Whenever a new method of production occurred, there was conflict between the older ruling class and a newer class using the newer and superior means of production. A new paradigm is the result of the conflict. An example is how the Businessman and his money destroyed the power of the old Aristocracy based on land and hereditary ownership. This becomes the basis of communism. 3 Turner: Geography and the Frontier Turner's thesis said that geography determines the character of a people and, depending on the situation, gives them certain advantages and disadvantages. An example is that England and Japan being island nations would naturally have an advantage in sea trade or battle. His thesis explicitly states how the Frontier shaped the American mind to be open to new things and to strive for what was new. Any group who lives near the "unexplored" will tend to have this characteristic. Radicals: History is the Story of Who Won This thesis says that history is little more than myth making. "Winners write history" Those who win write the history books. Those who have lost are excluded or demonized. History is determined by who has the political power to write the books. The point of view and prejudices of these dominate. Boorstin: The Unexpected Daniel J. Boorstin's books suggest a thesis that ideas and practices simply come together in various places and time and can hardly be predicted. What has mattered, is that the great Creators and Discoverers have been open to the challenge and took previously unrelated ideas and put them together in a way that was entirely new. Thus they change the world. Boorstin maintains that no one can predict or manage change. You can only remain open to it. The convergence of disparate elements creates history. Historical Forces Historical Forces claims that certain ideas have a life independent of the person who proposed that idea. The idea persists even after the person's death and continues to influence history. Examples would be Christianity after the death of Jesus, and Confucianism after the death of Confucius. Geographic Imagination 4 While these seem like hard and fast theories, our understanding of the world comes from a combination of influences, especially culture, language, and patterns of thought about the particular setting in which we are born and raised. We interpret the world around us based on our own unique understandings, perceptions, and knowledge. This particular world view or interpretation of the world is geographic imagination and is reflected in our behavior towards others and is manifested in the cultural landscape. Members of a particular social or ethnic group have a shared understanding of landscapes, places, and peoples. This common view of the world has been presented to the group over time by earlier generations and is accepted as truth and reality, especially where it concerns other groups. A problem arises when one’s particular world view shuts out alternative views. Ethnocentrism Avoiding Bias Four Rules Ethnocentrism leads us to believe that our way of thinking is the only or the best way of thinking about the world. All people, including archaeologist, tend to structure their interpretations of phenomena to reinforce the way they feel about the world. It is mainly how people feel about the world that determines how they interpret events, symbols and artifacts. To avoid bias, we should be concerned to provide as accurate information and conclusions as is possible. Fortunately, there is a way of evaluating conflicting claims about the past. We must evaluate the various claims and eliminate the least likely and the least useful. This, in essence, is the scientific method. Even with its imperfections, it is the best way we have for testing reality. We need a vocabulary and a method of judging information. In other words, we need some structure to organize reality. According to some schools of thought, an explanation must conform to four essential rules. 1. It must explain the maximum number of observations with a minimum number of assumptions. For example, the Law of Gravity covers everything that falls all over the world. There are few preconditions for this to happen. 2. An interpretation that is compatible with a well-established body of principles is better than one that does not comply with those principles. This approach is similar to the way we construct ideas about how the world works in our daily life. We reject ideas if they do not conform to concepts that we already hold with a good degree of certainty. 3. An interpretation must be tested before it can be accepted as useful and reasonably certain. But this testing aspect is commonplace in our daily lives. It is essential to the work of every mechanic, doctor, and do-it-yourselfer. They have interpretations of how things should work, what is wrong, and how to correct the problem. Then they test their interpretations and retest varying elements until they find a solution. 4. No interpretation can ever explain all observations relevant to it. This is the only law that has no exceptions! If you told a medieval monk about the law of gravity, he might say, “Even as you talk now, I see birds fly away from the earth, leaves tossed high in the air … Your so-called law is ridiculous. Exceptions to it abound everywhere.” 5 Exceptions to the rules How Probable is it? There can be exceptions because: observations can be affected by more than one principle, so that exceptions are bound to appear. For example, when hot air rises and contradicts the force of gravity errors in measurements, either human or mechanical, can occur. differences in perception; either honest or intentional exist. Different expectations of what ought to occur; frames of reference and points of view can make a difference. There are many conflicting ideas and points of view in history. Fortunately, there is a way of evaluating conflicting claims about the past. This, in essence, is the scientific method. In other words, we need some structure to organize reality. A way to rate explanations is to use the “Funnel of Certainty”. As explanations move up the funnel of certainty, they become more likely to be accurate. As they move down, they become much less likely. With little knowledge and scant information, we have the level of uncertainty. This is the “what is it? What does it do?” phase. At this point all explanations are equal. In the absence of evidence, everything is possible. History begins by asking questions to which there are no certain answers, this is the speculative phase. At this level, the possibilities begin to be narrowed. As investigations proceed, some solutions are weeded out by testing for example, using uniformitarianism (page 7). The possible solutions are progressively reduced to the level of probable, until relatively certain solutions are identified. Ultimately, laws are identified. A law is a statement of an order or relation of phenomena that so far as is known is invariable under the given conditions. For example, Malthus states that population invariably will outstrip resources (page 3). Some gap always remains between these explanations and reality, however. As new questions are introduced, they proceed through the funnel at rates that depend on the ease or difficulty with which they can be tested and answered. Interpretations 6 Scientists record and evaluate the most useful and broad interpretations of their observations and tests. These interpretations form a developed body of thought, which provides principles that guide further interpretations. This body of thought is generally referred to as theory. Theories give meaning to what we see in archaeology. It is interesting to note that philosophers of science generally agree that theories can never by totally proved or disproved since they are statements about abstract relationships. Only the hypotheses they generate can be proved or disproved. This moves the theory up or down the funnel of certainty. So a working definition of a theory is a framework by which we organize and understand the world around us today as well as the past. Criteria for judging theory Predictive Parsimonious This leads to the necessity for having a means by which to judge the validity and usefulness of a theory, A good theory or explanation has three characteristics: it is predictive, parsimonious, and powerful. Explanations that generate hypotheses that accurately predict what will be observed are obviously desirable. Thus if hypotheses derived from the theory of evolution predicts that transitional forms of fossils between apes and humans should be found, and subsequent excavation confirms that such transitional fossils really do exist, then the theory of evolution has better predictive qualities than any theory that does not predict the existence of such fossils. On the other hand, a theory that predicts the existence of such fossils and none are found is not predictive. An explanation is also considered to be good if it is relatively simple (parsimonious). The more complex the explanation the greater the likelihood that some part of it will be wrong. Ockham’s Razor, an idea that says the simpler of two competing ideas is the one to favor, applies here. This rule covers exceptions to rules as well. Powerful A good explanation is relatively powerful if it has scope and generality. Explanations that cover a broad range of phenomena are much more powerful than those that deal with a very narrow range of phenomena. Thus the theories of gravity and relativity are very powerful theories in the natural sciences. They apply to everything in the realm of science today. In contrast, a theory that explains a taboo on eating cows by reference to one particular country’s value system is less powerful because it accounts for only a limited range of phenomena in a single culture. These three characteristics need to be applied to every explanation and theory presented in this manual. Questions: Do your results match what was predicted? Is your explanation simple? Does your explanation cover a wide range of phenomena? Other Theories Catastrophism In the nineteenth century, there were three theoretical breakthroughs in explaining the past. Two of these were originally in the context of geology. The third was entirely the product of archaeological research. But first, let’s look at the prevailing theory of the time. Catastrophism is the argument that Earth's features—including mountains, valleys, and lakes—primarily formed and shaped as a result of the periodic but sudden forces as opposed to gradual change that takes place over a long period of time. For example, according to strict catastrophe theory, one might interpret the origins of the Rocky Mountains or the Alps, as resulting from a huge earthquake that uplifted them quickly. When viewing the Yosemite Valley in California a catastrophist might not assert they were carved by glaciers, but rather the floor of the valley collapsed over 1,000 ft (305m) to its present position in one giant plunge. 7 Creationism Catastrophism developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when, by tradition and even by law, scientists used the Bible and other religious documents as scientific documents. It is from the Bible we get the theory of Creationism. Creationism is a doctrine or theory holding that matter, the various forms of life, and the world were created by God out of nothing. Young Earth Creationists (YEC) claim a literal interpretation of the Bible as a basis for their beliefs. They believe that the earth is 6000 to 10,000 years old, that all life was created in six literal days, that death and decay came as a result of Adam & Eve's Fall, and that geology must be interpreted in terms of Noah's Flood. However, they accept a spherical earth and heliocentric solar system. Bishop James Ussher, a prominent theologian and Irish biblical scholar in the mid-1600's work, Annals of the World, counted the ages of people in the Bible and proclaimed that Earth was created in 4004 B.C. (In fact, Ussher even pronounced an actual date of creation as the evening of October 22), geologists tried to work within a time frame that encompassed only around six thousand years. Modern Interpretation Modern catastrophism argues evidence that catastrophic forces can have a profound influence on shaping Earth. For example, modern catastrophic theory argues that large objects from space (Asteroids, Comets, etc.) periodically collide with Earth and that these collisions can have profound effects on both the geology and biology of Earth. One hypothesis advances that a large asteroid impact lead to the extinction of dinosaurs roughly 65 million years ago. Three Good Theories The three good theories developed at this time were uniformitarianism, superposition and the three age theory. Uniformitarianism 8 James Hutton sought principles which would enable them to make sense of observations and unravel the geological history of the world. The theory he formulated, Uniformitarianism, states that events of the past must be explainable by processes that can be observed operating in the world today. For example, rivers today can be observed eroding riverbanks and shorelines As Hutton said, “The present is the key to the past.” This principle forms the foundation of contemporary geological and archaeological interpretation. In hindsight, many of the most important theories and laws seem almost embarrassingly obvious. The theory of Uniformitarianism is a very simple, powerful and predictive statement of relationships. Superposition What is the theory of superposition? Charles Lyell, the Father of modern geology, sensed that rocks formed layers like those of a cake. Perhaps he had helped his mother make cakes in the kitchen, putting down the bottom layer, then icing in the middle, then another layer, more icing, another layer and then the top icing. In any event, Lyell formulated and tested the theory of superposition which states simply that a layer of rock at the earth’s surface was deposited later than the layer under it, just as the top layer of cake is put in place after the other layers are in position. Lower is older. It unifies vastly different geological and archaeological phenomena and makes possible historical synthesis. The theory of superposition is everything a good theory should be: it is simple (parsimonious), it is powerful, and it is predictive. Three Age Theory To appreciate the three-age theory, we have to return to a time when it was believed that the earth was only a few thousand years old. It was 1816, and Christian Thomsen had just been appointed curator of the new Danish National Museum of Antiquities. Like many museums of the time, objects were chaotic and often arranged according to their donors. Christian Thomsen, confronted with just such a situation, began by sorting the museum’s oldest holdings into groups according to materials. Objects of stone were grouped together, and then those made of bronze, then iron. As he was handling these old objects, intuition must have dawned because Thomsen set forth the first scientifically based theory of cultural evolution. He argued that the human race had a stone technology (the Stone Age), gradually developed bronze tools (the Bronze Age), and finally developed iron tools (the Iron Age). When combined with the theory of superposition, this theory was quite easy to test. If both theories were correct, it would be possible to predict that when a site contained both stone and metal objects, the layers containing the stone would be lower than bronze or iron objects, and the layers containing bronze tools would always be found beneath deposits containing iron tools. These were the hypotheses derived from the theories, and they engendered tests in the form of excavations, the first scientific archaeological experiments and observations. For the first time, excavators began paying attention to layers or strata, in archaeological deposits. 9 The study of the sequences of these deposits became known as stratigraphy. Thomsen set archaeologists the task of determining whether this evolutionary sequence occurred everywhere in the world at the same time. This approach to the study of the past became known as the study of culture history. Archaeology’s role in history. Archaeology is the scientific study of past cultures and the way people lived based on the things they left behind. Archaeology is a branch of anthropology that seeks to document and explain continuity and change and similarities and differences among human cultures. Archaeologists work with the material remains of cultures, past and present, providing the only source of information available for past non-literate societies and supplementing written sources for historical and contemporary groups. Things are not just the solid material objects; they are also the basic symbols that confront archaeology. For example, a pot is a pot, but it is also a symbol of the way clay was shaped and treated by a particular people at a particular time. It is a symbol of the way they solved problems of food preparation. It is a symbol of the way labor and society were structured, a symbol of trade, a symbol of status, and many other things. Archaeologists study past cultures by examining artifacts, objects made, used, or changed by humans. Things that have been modified by human beings are referred to as artifacts. They can be made of stone, bone, clay, metal, wood or any other natural material. In modern times we can add synthetic materials to this list. Modification can consist of major or minimal alterations to the naturally occurring shape. Artifacts Artifacts can convey information beyond their function. Those which are strictly useful are labeled technic or technomic. Artifacts which show a social class are labeled socio-technic. They are still useful but their materials or decoration set them apart from the ordinary. The cup on the right is an example of a sociotechnic artifact since it is made of jade and gold with an intricate design. Finally, artifacts which show a relationship are labeled ideotechnic. Things such as a crown or scepter, a cross or a star of David are ideotechnic. 10 . Historic vs. Prehistoric Any place where human activity occurred and where artifacts are found is called an archaeological site. There are two types of archaeological sites, prehistoric and historic. Prehistoric sites are those which occurred before the culture began writing records. Prehistory is more of a puzzle because most of what we know about prehistoric people is from the artifacts they left behind. That means archaeologists must try to understand how the artifacts were used. Due to this, archaeologists sometimes make incorrect inferences or guesses. Historic sites are sometimes easier for archaeologists to interpret because documents and drawings are available, aiding an archaeologist's understanding of the site. Sources A source is anything that survives from the past or tells us about the past. Sources are ecofacts: those things left behind that are natural such as seeds, bones; features: items too large or permanent to be taken to a lab, a city wall; relics: artifacts; any material thing made or modified by humans records: written or printed documents, paintings. Ecofacts Ecological items that become associated with a site through natural processes, such as pollen deposition or natural preservation of insect remains, are called ecofacts. They include seeds, wood remains, pollen, small burrowing snails, owl pellets, and the remains of small pests, anything that provides information on the ecological setting of the sites. These items are clues to the past climate and ecology of the site. The picture on the right is an insect encased in amber. Things that cannot be taken back to the laboratory for analysis because they are actually part of the earth or because moving will alter or destroy them are called features. Postholes, pits, house floors (see picture on the left), mounds, cairns, middens are all features. Because features are sometimes indicated by very subtle changes in the color or texture of the earth, their proper excavation and recording is Features very important. Relics Many people are interested in the past. Artifacts like pottery, arrowheads, cave paintings, etc. are relics These relics tell us of the past before written sources. Remember, an archaeological site is like a book. The layers of dirt and artifacts that are left in the ground can be read like the pages of a book. When someone digs holes in an archaeological site, it is like ripping pages out of the life stories of past peoples. The application of the Three Age Theory and Superposition help to interpret and date the relics found in a site. 11 Written Sources Records It is not until the invention of writing that we have records. Although some records seem easy to understand, it is more difficult to make sense of others. You can often make better sense of historical records if you recognize and understand specialist or archaic words and languages. Individual word meanings might have changed over time and the meanings and values of the period are different from those of today. Primary Sources A primary source is a document or physical object which was written or created during the time under study. These sources were present during an experience or time period and offer an inside view of a particular event and provide historians with the facts with which to work. Some types of primary sources include: Secondary Sources original documents (excerpts or translations acceptable): Diaries, speeches, manuscripts, letters, interviews, news film footage, autobiographies, official records creative works: Poetry, drama, novels, music, art relics or artifacts: Pottery, furniture, clothing, tools, buildings, etc. A secondary source interprets and analyzes primary sources. These sources are one or more steps removed from the event. They are reports about the primary source or collections of information about the subject. may have pictures, quotes or graphics of primary sources in them. Some types of secondary sources include textbooks, magazine articles, histories, criticisms, commentaries, encyclopedias. How to find Validity of a secondary source To determine accuracy in Secondary sources, ask analytic questions: WHO recorded this information? A witness? A close friend? A monk nine hundred years after the fact? A respected scholar who has studied all available sources? WHAT does the source say about the events, persons or trends? WHERE were they during the time period or event he/she discusses in the record? Front row? Two continents away? In the same house but out of earshot? WHEN did they record the events? The same day? Twenty years later? Two hundred years later? WHY did the author make this particular record? Scholarly interest? Personal journal? As propaganda for a particular organization or ruler? Armed with these tools, we can now begin our exploration of Origins in History 12 WHAT IS MEANT BY ANALYZING BIAS/POINT OF VIEW IN HISTORICAL SOURCES? Pennsbury School Simply put, your task is to act as an historian sifting through sources. Part of this job involves you reviewing the source of the document and understanding why the sources said or wrote what is in the document. In other words, you are analyzing what it is about the source that made them say or write what is in the document. In the end, you are measuring the credibility, legitimacy, reliability, and pertinence of the source. The crucial skill a DBQ demands of students is the awareness that documents are not statements of facts, but descriptions, interpretations, or opinions of events and developments made by particular people at particular places and times, and often for specific reasons. Students should be applying critical thinking skills to documents, evaluating whether they are likely to be accurate and complete, and how the author of the document may be revealing bias. WHERE DO YOU FIND BIAS/POINT OF VIEW IN THE DOCUMENTS? One will find bias/point of view in the documents by looking at the source of the document. Look for sources that, by their nature, may be of interest. Remember, what is in the document will verify whether the source’s point of view is of interest. Authorial point of view: Show awareness that the gender, occupation, class, religion, nationality, political position, or ethnic identity of the author may well have influenced the views that are expressed. For example: George Marshall, the American Secretary of State, was naturally concerned with the chaos and poverty in Western Europe in 1947, as it was his duty to protect American interests abroad. The potential spread of Communism into Western Europe would have threatened these interests. Reliability and accuracy of the source: Critically analyze a source for its reliability and accuracy by questioning whether the author of the document would be in a position to be accurate and/or would be likely be telling the truth. You can also evaluate the type of source, such as a letter or official report, showing an understanding that different types of sources vary in their probable reality. 1. For example: George Kennan’s telegram reporting on the nature of the post-war Soviet Union is probably accurate because, as an American ambassador living in Moscow, Kennan would have first-hand insight into the Soviet government. 2. OR: George Kennan’s telegram reporting on the nature of the post-war Soviet Union is probably inaccurate because, as an American, Kennan would have only a limited understanding of the inner workings of the Soviet government, despite his presence in Moscow. Tone or intent of the author: In this case, you examine a document to determine its tone (satire, irony, indirect political commentary) or the intent of the author. This may be particularly useful for visual documents. o 1. For example: Dr. Seuss drew his World War II era cartoons to mock Americans who still supported isolationism for their ignorance and to warn Americans of the dire consequences of not becoming involved in European affairs. 13 Viewing Guide “Changing Knowledge, Changing Reality.” The Day the Universe Changed. By James Burke. SVE & Churchill Media. 2004. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LzZATr-c8Y Visual Clues Concepts Witch Trial What is knowledge? What is the role of knowledge? How could actions be justified? “hollow face” Function of structure How do we structure reality? Role of interpretation Hill Town Frame of reference What does it do? Purpose of structure of reality. Why structures change 14 Notes Sources Consulted Burke, James. Changing Knowledge, Changing Reality. 1985. PBS. DVD. Fenton, Edward. “History as Interpretation.” Out of Print. Hayden, Brian. Archaeology: The Science of Once and Future Things. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1993. Silva, Brett. “Historiography.” 14 March 2006. Chico Unified School District, Chicago, Illinois. http://ibatpv.org/ib/histo.html Stearns, Peter. "Why Study History." American Historical Association. N.p., 11 July 2008. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. "What Is Archaeology?" Alabama Archaeology. U of Alabama, 24 June 2005. Web. 5 Dec. 2011. <http://bama.ua.edu/~alaarch/Whatisarchaeology/>. 15