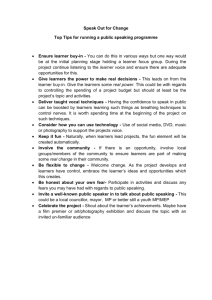

Illustration 3: Organization of a Learner Web region (example from a

advertisement

EDG 6931 Distance Education Leadership and Management Dr. Cathy Cavanaugh Spring 2, 2010 The Learner Web A case study submitted by Jan Hendrik Beck The present study investigates the Learner Web, an innovative learning platform for different target audiences developed at Portland State University in Portland, OR. The study is divided into three major parts. The first part describes the Learner Web as a program. The second part provides a handson introduction to the Learner Web’s learning environment. The third part analyzes the Learner Web according to a number of success factors covered in our class and gives some recommendations for future distance education leaders. This paper contains audio and video hosted on the websites on the Internet. It is thus best read on a computer with an Internet connection. 1. Description of the Learner Web 1.1 Overview of the program The Learner Web is an online “learning support system” (Reder, 2010a) designed to provide adult learners with learning resources and guidance in a variety of fields. The original version of the Learner Web was created in response to findings of the Longitudinal Study of Adult Learning (Reder, 2010b), a large-scale study being conducted at Portland State University, following the learning development of adults who dropped out of high school before graduation. One of the findings of the study was the value of self-study activities in context of GED preparation. Reder & Strawn (2006a; 1 2006b) report that adult learners who engaged in self study were more likely to obtain a GED than those who relied only on adult education classes (27% success among students who used both self study and classes; 24% success among students who used self study only; 17% success among students who relied on classes only). There are many reasons why self study is such an important factor for learning success among adults. Perhaps most importantly, adult learners often have busy and frequently changing schedules. This makes it hard for them to commit to physical classes running on a fixed schedule. In addition, many adults feel that it is easier to learn in a context that allows them to focus on exactly the areas they need in order to reach their educational goals. However, studying alone and without support from teachers or tutors can be a daunting endeavor. Without a plan and a clear structure, learners find it hard to stay motivated and often do not even know what to study or how to study effectively. This is especially true for adult basic learners, who often have little experience with formal education. Besides a lack of academic background, these learners know very little about how the education system works. For example, Reder (2010a) mentions the case of an adult learner whose goal it is to become a medical doctor but does not know that a college degree is required to attend medical school. The original Learner Web set out to address both the “what” and the “how” of adult learning. The basic idea was (and still is) to provide the learners with the learning contents needed to reach their specific educational goals and with learning plans to structure the learning experience. Learning plans are curricular units corresponding to specific learning goals. In other words, they are the Learner Web’s “courses” and can vary in length anywhere from a few hours to a 2-credit term-long class. The learning contents are not always created by Learner Web staff. In fact, an important characteristic of the program is that the learning plans often incorporate contents that already exist online. A particular strength of this approach is that the Learner Web can use authentic materials such as YouTube videos, text passages, and music, embed them in learning plans and thus transform them into meaningful 2 learning resources. Especially in language teaching, task-based learning and the use of authentic materials have become very popular in recent years (e.g. Eckerth, 2008)) owing to their value in preparing learners for real-world contexts. Web-based resources are not the only types of contents used in the Learner Web. Individual regions (see below) often offer learning plans incorporating local resources available to the user. For instance, a career preparation learning plan written for users in the St. Paul, MN area may point the learners towards offline resources in their area, such as community colleges, library courses, and educational workshops. One of the Learner Web’s goals is to connect its users to the communities they live in and introduce them to resources which the learners might not even know exist. Another advantage of linking online guided self study with local offline learning is that the Learner Web can serve as a “medical chart for learning” (Reder, 2010a). As learners shift in an out of local programs, the Learner Web can keep track of their progress and learning goals achieved. Originally designed to assist adult basic learners in their efforts to prepare for GED examinations, the Learner Web today caters to a variety of audiences: Immigrants to the US, adult basic learners, job seekers, and international and domestic college students. Illustration 1 provides an overview of the Learner Web’s primary strategic directions. Adult education encompasses areas like basic skills (math, literacy, etc.), career preparation and development, citizenship preparation, and English for work. In addition, the Learner Web has been adopted by Portland State University’s ESL program and its nationally acclaimed University Studies program. Besides these primary fields, the Learner Web is also used in some other contexts, for instance, in skills assessment and to train new Learner Web staff and instructors. Learner Web courses are usually self-paced and the users study on their own, but tutors and support staff are always available online and through a toll-free phone number. 3 Illustration 1 – Strategic directions of the Learner Web (The Learner Web Project, 2010) As mentioned, the Learner Web strives to connect learners to their communities and local resources. Because of this and because of its focus on self study, the Learner Web does not see itself as a “traditional” distance learning program: Most distance education programs are organized around a class format directed by an instructor. The Learner Web [in contrast] supports individuals independent from a class or an instructor. The Learner Web can incorporate classes and distance education programs if desired. (Learner Web Project, 2010) 4 This is, however, not to say that certain parts of the Learner Web are not comparable to distance education programs. Independent studies and distance education are by no means mutually exclusive,1 and the Learner Web’s learning plans are not all that different from course curricula. The Learner Web is interesting from the perspective of distance education leadership because of its ability to blend traditional classroom-based learning with web-based technologies. It is important to keep in mind, though, that that the Learner Web is neither one program nor simply a learning management system. The next section looks at the Learner Web’s organization and sheds some light on the variable nature of the Learner Web as a learner support system. 1.2 Organization and leadership structure The Leaner Web is organized in a network consisting of several different regions. These regions are geographically and/or thematically distinct nodes in the network, usually belonging to different regional partners, which could be a state, a city, and organization, a university, or a department within the university. At the core of the Learner Web project is National Implementation Team, lead by Dr. Stephen Reder at Portland State University. This expert group is responsible for developing, reviewing, and reevaluating the program’s vision, setting the major strategic directions, and expanding the Learner Web. However, the actual organization of the Learner Web is strictly decentralized and without a central governing body. When a new regional partner comes aboard, the National Implementation Team trains new the new staff and helps the region get started. From that point on, the regional partner makes its own decisions about learning plans, contents, and target audiences. Even major decisions concerning the Learner Web as a whole are made in close collaboration with all relevant stakeholders. The organization of the Learner Web can thus be described as in illustration 2: 1 Consider Louisiana State University as just one of many examples of established universities offering for-credit courses in a self-paced, self-study format: http://www.is.lsu.edu/courselist.asp?level=CO&online=0&nid=102 5 Portland State University Scotland, UK Portland, OR National implementation team Greater Boston St. Paul, MN New York State Illustration 2: Organization of the Learner Web. The outer ring shows some of the Learner Webs regions. The illustration only shows a few example regions. The full list of regional partners and other partners can be accessed at http://www.learnerweb.org/infosite/currentPartners.html. As can be seen, Portland actually has two different regional partners: one is for the Portland community and is open to anyone. The other region belongs to Portland State University and is restricted to students at the university. The Portland State node actually consists of several regions, for faculty development, ESL students, University Study students, etc. Similarly to the Learner Web’s organization on an international level, the administration within a region is very flat in terms of hierarchy. The regional administrator initiates and oversees the development of new learning plans and contents in accordance with other possible stakeholders (e.g. non-Learner Web managers of education) in order to make sure that the entire program benefits from the new learning plans. Content developers and learning plan developers deliver the contents of the region. The difference between the two positions is that content developers are solely concerned with 6 the writing of materials, whereas learning plan developers are instructional designers responsible for implementing all materials into the learning plan. Besides these key positions, there is a plethora of tutors, course instructors, and technical support staff to support the learners online or onsite, as shown in illustration 3. Content developers Regional administrator National implementation team Regional implementation partner Faculty and instructional managers Regional implementation partner Tutors and tech support Learning plan developers Illustration 3: Organization of a Learner Web region (example from a university region) This structure may change as the Learner Web grows from an academic project to a sustainable, possibly even profitable, organization. Advantages and challenges of the current structure will be discussed in a later in the paper. 1.3 Accreditation and funding Although the Learner Web is growing rapidly and even beyond US borders, it is at this point still an academic project. It is thus not accredited by any professional or academic associations. Funding comes from grants and from the organizations implementing it for their purposes. According to Dr. Reder (2010a), the Learner Web may be headed towards becoming an independent organization. The next section provides a hands-on introduction to the Learner Web. 7 2. The Learner Web hands-on Complementing the theoretical description in the previous sections, it seems useful to have a more hands-on tour of the Learner Web in order to get a better impression of what a learner in the program would see. The Learner Web’s main website can be accessed at www.learnerweb.org and the individual regions as well as an overview of all Learner Web partners can be found at http://www.learnerweb.org/infosite/currentPartners.html. The screenshot below shows the welcome page of Portland State’s Intensive English Language Program region. The simplicity of the layout is common to all Learner Web regions and contents, and is intentional. A simple “no bells” interface means fast accesses even from slow Internet connections. 8 Learning plans do, of course, contain resource-heavy materials such as movie clips, animations, and graphics, but the actual Learner Web interface is always as simple as the one in the screenshot. The minimalistic design has another great advantage: Many of the Learner Web’s regions serve users who do not always have high computer literacy. Keeping the interface simple is vital to helping these users to navigate the Learner Web contents with easy and helps them stay motivated. Most Learner Web regions are open and free to all interested users, but since every new user means administrative effort for the given region, I decided to leave registration to those users who are actually going to use the region. Instead, Errin Beck, one of the regional administrators at Portland State’s Intensive English Language program was kind enough to give me a tour of one of the region’s learning plans. The link below leads to a 5-minute video, in which Errin explains the basic of a learning plan and its interface: LW Demonstration Video (This video was created using Jing by TechSmith.) 9 3. Success factors Amidst the wealth of options available to learners in any field, online programs must identify and market areas in which they are better than the competition. Such areas might be quality, cost, reputation, convenience, length of the program, and many more. As an open learning environment serving the community, the Learner Web is not in competition with other institutions for funds and students, but it still needs to attract and retain learners if it wants to be a useful resource.2 Cost: The community-based regions of the Learner Web are free to use. Even the technical phone support and face-to-face (or online) tutoring are available free of charge. The learners do not have to purchase textbooks or any other materials. Convenience: No attendance is necessary. Many adult learners are too busy to attend face-toface classes. The Learner Web lessons are self-paced and adapt to the learner’s busy schedule. Joining the Learner Web is a matter of a simple one-step registration, and users can jump from region to region, using one account. Comfort: Many adult learners, especially in basic skills and ESL settings are intimidated by large face-to-face classes. In some cases, adults are uncomfortable in formal education settings because they are not legal residents or because cultural norms do not allow them to mingle with strangers. For these people, the Learner Web offers a safe and comfortable learning environment Scope: Adult learners have very little time and tolerance for learning contents they perceive as irrelevant. In face-to-face classes and other group settings, instructors and curriculum designers 2 The university-based Learner Web regions at Portland State University work differently as they are only open to participants in the university community. 10 are unable to focus on the needs of individual learners. The Learner Web allows its users to access exactly the content areas they need. Connections to the community: The Learner Web does not want to compete with other resources such as community colleges or community learning centers. Rather it seeks to complement the offerings of these organizations. In many cases, such as vocational Learner Web learning plans suggestions are built in as to which community resources are relevant to the learner. Simplistic navigation and tools: As mentioned above, the Learner Web has a simplistic design and is easy to navigate, which makes it especially attractive to members of the community with low computer literacy. Quality: Community-based learning programs are often characterized by goodwill rather than academic rigor. Learner Web curricula, on the other hand, are designed by experienced instructional designers who are familiar with how adult learners learn best and behave in different learning environments. All these factors make the Learner Web attractive to its target audience, but there three other important success factors making the Learner Web a viable project from the perspective of its administrators and sponsors. Both of these factors can be linked to the decentralized organization of the Learner Web: Distribution of operating costs: In times of tight budgets and dwindling government support for education, non-profit programs often struggle finding a steady source of income. In the Learner Web, the regional implementation partners are responsible for funding their region. This way, the financial burden is not on a single governing body. If in the worst case a region fails, the others can continue their work relatively unharmed. 11 Thought leadership: The absence of one decision maker or central board of decision makers allows the partners in the Learner Web total creative freedom when it comes to developing learning plans and contents. As Professor Reder (2010b) mentions, it has happened that regional partners came up with uses for the Learner Web that he and his developer team never even thought of. Sharing of ideas and cloning of learning plans: A region that has developed a new learning plan may decide to share its work with other regions in the Learner Web. The other regions are then free to adapt the new plan to their individual context (e.g. in terms of community resources embedded). It also happens that a region decides to write a new plan building on a shared plan it received and then in turn shares this new plan with the other regional partners. In this way, knowledge, ideas, and products multiply, and each region can offer much more than its resources allowed if it were alone. Table 1 below presents a synthesis of the US regional accrediting commissions’, Statement of Commitment for the Evaluation of Electronically Offered Degree and Certificate Programs (Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions, 2000; Parker, 2008). Together with the Best Practices for Electronically Offered Degree and Certificate Programs by the Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications (e.g. Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions, 2000), the standards form the basis of 24 benchmarks proposed by the Institute of Higher Education Policy. It is difficult to evaluate a relatively young program open learning system like the Learner Web, using benchmarks designed for established programs. However, the standards are broad enough to serve as a general orientation to quality and applying them to the Learner Web helps to confirm that the program is indeed on the right way. 12 Involvement of competent professionals in creating, providing, and improving the program Instructors, instructional designers, researchers, and graduate students work collaboratively Interactivity Limited in a guided self-study environment. But tutors and instructors are available for help, and community resources are available. So far no interactivity between the students. Integrity, organized curricula, and clear learning outcomes Every learning plan starts with a clearly defined learning goal. Every learning plan tells the user exactly what he or she will be able to do after completion. Addressing student needs and providing resources needed for learning success Learners only focus on learning plans that are useful to them. All resources needed to complete a learning plan are available online and ready. The user does not have to purchase anything or search for resources online. Accountability of the institutions for their programs Each partnering organization/institution is responsible for their contents. Continuous assessment and improvement of learner success Some regions and learning plans offer feedback to the learner. Learner assessment is possible when the learner submits his or her work to a tutor. Selfassessment is also a feature which a learning plan developer may choose to include. Peer review Continuous peer review through sharing of learning plans, and local and national conferences. The final section gives some recommendations for aspiring leaders in distance education by leaders of the Learner Web. In their own words: summary and recommendations The Learner Web is a young but ambitious project and is quickly spreading across the US and beyond. As a learner support system it combines self study with community-based learning and online contents with offline resources. In its current form, the Learner Web can afford a flat hierarchical 13 organization that allows for maximum creative freedom for individual developers and whole partnering organizations. Leadership in the present Learner Web is much more about vision and engagement than about authority. It will be interesting to see how the organizational structure of the Learner Web will change as the program grows and develops. This case study closes with a few select comments on leadership from the two Learner Web leaders that were interviewed for the leadership podcast, Dr. Reder (2010b), Principal Investigator of the Learner Web, and Darby Smith (2010), Regional Administrator. “Ideas, not people” In long-term projects, people come and go. A project succeeds when it does not depend on individuals but when there is a vision that is shared by everyone involved. “Be flexible” Sometimes it is impossible to say where a project will go and how exactly it will develop. Leaders and project sponsors have to accept that not all factors can always be controlled for if they want to inspire innovation. “Be willing to fail” The risk to fail is part of any new endeavor. “You have to believe in what you are doing but you have to be willing to fail. If you are so averse to being wrong, you can’t get very far” (Reder, 2010b) “Incubate ideas” Don’t try to come up with all the good ideas yourself. Rather create an environment that incubates good ideas and though leadership among those who work with you. 14 “Lead gently” In education, you work with a lot of people who are experts. Instructors are used to being in charge of everything that goes on in their classrooms. This is no different in online environments, and you need to lead very gently so as not to interfere with your teachers’ professional pride. References and websites Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (2000). Statement of Commitment for the Evaluation of Electronically Offered Degree and Certificate Programs. Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.educause.edu/Resources/StatementofCommitmentbytheRegi/151503 Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (2000). Best Practices for Electronically Offered Degree and Certificate Programs Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.educause.edu/Resources/BestPracticesforElectronically/151504 Eckerth, J. (2008). Task-based language learning and teaching - old wine in new bottles? In J. Eckerth & S. Siekmann (Eds.), Task-based language learning and teaching. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang. Parker, N.K. (2008). The quality dilemma in online education revisited. In T. Anderson (Ed.), Theory and practice in online learning (305-340). Retrieved April 24, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120146 Reder, S. (2010a). Personal interview. UF Leadership Podcasts. Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://online-educator.pbworks.com/Leaders-podcasts Reder, S. (2010b). LSAL. The longitudinal study of adult learning. Retrieved March 10, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.lsal.pdx.edu/ 15 Reder, S. & Strawn C. (2006a). Self-study: broadening the concepts of participation and program support. Focus on Basics, 8, 6-10. Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.ncsall.net/?id=1152 Reder, S. & Strawn C. (2006b). The Learner Web. Brief concept description. Learner Web project. Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.learnerweb.org/infosite/Attachments/LearnerWebConceptBrief.pdf Smith, D. (2010). Personal interview. UF Leadership Podcasts. Retrieved April 26, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://online-educator.pbworks.com/Leaders-podcasts TechSmith Corporation (2009). Jing. http://www.learnerweb.org/infosite/ The Learner Web Project (2010). The Learner Web. Retrieved April 23, 2010, from the World Wide Web: http://www.learnerweb.org 16