3/4/2013 - New York University

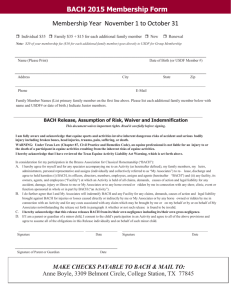

advertisement