Chapter 5

The Neolithic Revolution

Origins Agriculture and Urban Life

The transition from nomadic to sedentary lifestyle lays the foundation for

the development of the city. Environmental conditions and technological

advances are highlighted as co-drivers of the profound change in lifeways.

The beginnings of social classes and new strategies in social control are

emphasized. The urban revolution covers the origins of the institutions

that make city life possible. The systems needed to sustain large numbers

of people living in close proximity are discussed and the issues arising

from such proximity are examined. The development of government,

economy, religion, and infrastructure take center stage.

Pages 72

Effects of Climate

Pages 73-75

Domestication and Horticulture

Pages 75-77

Pastoralism

Pages 77-78

Spread of Agriculture

Pages 78- 81

Effects of Agriculture

Pages 82- 90

Document Based Question

Pages 91

Works Consulted

Essential Question: How do Sedentism and agriculture make civilization possible?

What is the

Neolithic

Revolution?

Younger Dryas

The Great

Conveyor Belt

End of the Ice

Age

The Neolithic Revolution is the tem used to describe the transition from nomadic

hunting and gathering societies to settled agrarian societies. Taken as a whole, from

start to finish, the transition certainly was a revolution in the entirety of changes it

brought in the way people lived. Considered over the entire 250,000 year span of

human existence, the several thousand years it took was relatively sudden. The

changes in any given lifetime were imperceptible. Cumulatively, over time, they

were enormous. The transition took place where both the Paleolithic hunting and

gathering and Neolithic gardening ways of life could co-exist .

According to the University of Nebraska Lincoln, Harvard professor Dr. Ofer BarYosef believes that people began to cultivate and store crops because the cold, dry

weather during the time period led to a reduction in wild food sources. The earliest

evidence of agriculture is dated around the end of the Younger Dryas.

The Earth's climate began shifting from a glaciated state to warmer temperatures

around 14,500 years ago. However, just as the ice was retreating in the northern

hemisphere, temperatures reverted back to near-glacial conditions and remained cool

for another 3,000 years. Some researchers believe the Younger Dryas occurred

because the rapidly melting ice sheets added a great deal of freshwater to the North

Atlantic and reduced the salinity levels of the ocean. This slowed down the ocean's

currents, which warmed the southern hemisphere and cooled the northern regions

.The great ocean conveyor

belt is a vital component

of the global ocean

nutrient

and

carbon

dioxide cycles. Warm

surface

waters

are

depleted of nutrients and

carbon dioxide, but they

are enriched again as they

travel

through

the

conveyor belt as deep or

bottom layers. The base of the world’s food chain depends on the cool, nutrient-rich

waters that support the Some researchers believe the Younger Dryas occurred

because the rapidly melting ice sheets added a great deal of freshwater to the North

Atlantic and reduced the salinity levels of the ocean. This slowed down the ocean's

currents, which warmed the southern hemisphere and cooled the northern regions.

Fourteen thousand years ago, the Ice Age was coming to an end and temperatures

were warming very quickly. Food became available in relative abundance for the

first time in thousands of years. Instead of having to travel long distances to find

food, some groups were able to live in the same place all year round. People started

to build permanent dwellings. By 10,000 BC, the end of the Younger Dryas period,

they were discovering that certain animals, such as goats, sheep, cattle and pigs, had

temperaments and dispositions that made them easy to manage within close

proximity to their dwellings. They selected and cultivated certain grains, such as

oats, wheat and barley, which provided nourishment to larger groups of people and

would last for long periods without spoiling.

72

Domestication

The domestication revolution was the transformation of human society brought

about by the domestication of plants and animals for food production, leading to

horticultural and pastoral societies. The domestication revolution was the first

dramatic transformation in the nature of human societies. While this revolution

took place over a very long period of time, it marked a dramatic change in the

nature of societies. The domestication revolution marked the first successful

effort by people to use social organization to gain greater control over the

production of food and improve their lives. The availability for the first time in

human history of a dependable food supply unleashed a whole chain of events

that changed society forever.

Horticulture

The peoples who first cultivated cereal grains had long observed them growing in

the wild and gleaned their seeds as they

gathered other plants for their leaves and roots.

In Late Paleolithic times both wild barley and

wheat (see chart left) grew over large areas in

present-day Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Jordan,

Lebanon, and Israel. Hunting-and-gathering

bands in these areas may have consciously

experimented with planting and nurturing

seeds taken from the wilds or they may have

accidentally discovered the principles of

domestication by observing the growth of

seeds dropped near their campsites.

Cultivation

Gardening

73

Cultivation of plants on a small scale may have been practiced for many

thousands of years. The protection and encouragement of the growth of wild food

plants through weeding, pruning, irrigation, and pest control, along with the

simple propagation of seeds or cuttings, most likely constituted some of the first

human horticulture. The use of fire to remove dead vegetation and promote the

new growth of desirable plants is another example of how ancient humans

engaged in plant cultivation. Repeated harvestings engaged collector and

collected in a positive feedback-natural selection process that changed the

domesticate species genetically to favor its selection and reproduction. Over time,

passive gathering became active planting, tending and harvesting. A garden,

being a more or less permanent location, forces those who tend and harvest the

garden to remain in the same place for longer periods of time.

Because garden produce has value, a group of humans must cooperate to the

extent that they can protect themselves and their produce from those who would

rather steal it. Many of the earliest horticulturalists also lived in fortified

communities. There is safety in numbers, and there is safety in walls. An

important element is having the wherewithal to store food for future

consumption, trade or ceremonies. Gardens were outside the village walls and

people came into the village at night for protection from animals and bandits.

Storage

Transition

to Farming

Climatic

Shifts

The evolution of agriculture can also be traced through the evolution of containers,

essential for storing surplus harvests.

Nomads favored portable leather or straw

baskets and also dug underground storage

pits. When people began to live in permanent

settlements, they built heavier but more

functional storage containers from clay that

they dried in the sun. Sharing food remains a

crucial element of many, if not most, human

ceremonies. Settling down in a community

does not lead to gardening -- gardening leads

to settling down in communities.

Because there are no written records of the transition period between 8000 and

5000 B.C. when many animals were first domesticated and plants were cultivated

on a regular basis, we cannot be certain why and how some peoples adopted these

new ways of producing food and other necessities of life. Climatic changes

associated with the retreat of the glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age (about

12,000 B.C.), may have played an important role. These climatic shifts prompted

the migration of many big game animals to new pasturelands in northern areas.

They also left a dwindling supply of game for human hunters in areas such as the

Middle East, where agriculture first arose and many animals were first

domesticated.

Climatic shifts also led to changes in the distribution and growing patterns of wild

grains and other crops on which hunters and gatherers depended. In addition, it is

likely that the shift to sedentary farming was prompted in part by an increase in

human populations in certain areas. It is possible that the population growth was

caused by changes in the climate and plant and animal life, forcing hunting bands

to move into the territories where these shifts had been minimal. It is also possible

that population growth occurred within these unaffected regions, because the

hunting-and-gathering pattern reached higher levels of productivity. Peoples like

the Natufians found their human communities could grow significantly by

intensively harvesting grains that grew in the wild. As the population grew, more

and more attention was given to the grain harvest, which eventually led to the

conscious and systematic cultivation of plants and thus the agrarian revolution.

74

It is probable that the earliest farmers broadcast wild seeds, a practice that cut down

on labor but sharply reduced the potential yield. Over the centuries, more and more

care was taken to select the best grain for seed and to mix different strains in ways

that improved both crop yields and resistance to plant diseases. As the time required

tending to growing plants and the dependence on agricultural production for

subsistence increased, some roving bands chose to settle down while others practiced

a mix of hunting and shifting cultivation that allowed them to continue to move about.

Pastoralism

Nomads vs.

Sednetary

During the Ice Age, vast areas of the Earth were covered by grasslands grazed by

huge herds of animals such as bison and reindeer. However, as it began to some to an

end between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago, the climate became warmer and wetter,

and the forests started to spread. Herds of large animals became scarcer, and in many

places people were forced to find new sources of food, hunting small game such as

deer or wild sheep, catching birds and fish and gathering shellfish and edible plants.

To ensure a reliable source of food, some people began to manage herds of wild

animals by keeping some in pens until needed. The domestication of animals gave

rise to pastoralism which has proven the strongest competitor to sedentary agriculture

throughout most of the world. Pastoralism has thrived in semiarid areas such as

central Asia, the Sudanic belt south of the Sahara desert in Africa, and the savanna

zone of East and South Africa. These areas were incapable of supporting dense or

large populations.

The nomadic, herding way of life has tended to produce

independent and hardy peoples, well-versed in the military

skills needed not only for their survival but also to challenge

more heavily populated agrarian societies. Horse-riding

nomads who herd sheep or cattle have destroyed powerful

kingdoms and laid the foundations for vast empires. The

camel nomads of Arabia played critical roles in the rise of Islamic civilization. The

cattle-herding peoples of central, East, and South Africa produced some of the most

formidable preindustrial military organizations. Only with the rather recent period of

the Industrial Revolution has the power of nomadic peoples been irreparably broken

and the continuation of their cultures threatened by the steady encroachment of

sedentary peoples.

Though several animals may have been

domesticated before the discovery of agriculture,

the two processes combined to make up the critical

transformation in human culture called the

Neolithic (New Stone Age) revolution. Different

animal species were tamed in different ways that

reflected both their own natures and the ways in

which they interacted with humans. Dogs, for

example, were originally wolves that hunted

humans or scavenged at their campsites. As early

as 12,000 B.C., Stone Age peoples found that wolf

pups could be tamed and trained to track and corner

game. The strains of dogs that gradually developed proved adept at controlling herd

animals like sheep.

75

Relatively docile and defenseless herds of sheep could be controlled once their leaders

had been captured and tamed. Sheep, goats, and pigs (which also were scavengers at

human campsites) were first domesticated in the Middle East between 11,000 and

9,000 B.C. Horned cattle, which were faster and better able to defend themselves than

wild sheep, were not tamed until about 10,000 B.C.

Why

domesticate?

Role of Women

The central place of bull and cattle symbolism in the

sacrificial and fertility cults of many early peoples has

led some archeologists to argue that their domestication

was originally motivated by religious sentiments rather

than a desire for new sources of food and clothing.

Domesticated animals such as cattle and sheep provided

New Stone Age humans with additional sources of

protein-rich meat and in some cases milk. Animal hides

and wool greatly expanded the materials from which

clothes, containers, shelters, and crude boats could be

crafted.

The central role of women in horticultural societies had political and sociological

consequences. Even in Paleolithic times, nature was seen as feminine. Woman was

the vehicle of nature which gave and nourished life. It was the women who owned

and managed their garden plots and passed them on to the next generation. It was the

women who decided when their soil was

depleted and where the village should move.

One of the interesting aspects of horticultural

societies is that it is often women who exercise

political power and authority in their society.

Horticulture was the critical intermediate step

between hunting and gathering and fully

developed agriculture.

Shift to mixed

Farming

Effects

A later shift from small plot horticulture to large field crop agriculture occurred with

the introduction of domestic animal power as well as metal working technologies. It

was at this stage that agriculturalists could afford to abandon their former hunting

ranges altogether and to settle permanently in the prime agricultural lands of river

valleys with their rich alluvial soils. It was also at this stage, with its heavier field

work and animal husbandry, that men took control of the land and animals and

resumed their dominant position in society over women. The importance of the slow

Why Change?

technological and economic development that led many societies from hunting and gathering

economy to plant cultivation and animal husbandry is indeed enormous. I t permitted a vast

transformation of human life and activity, involving both a demographic increase and the rise

of more complex human settlements and communities. Agriculture required an increasingly

greater specialization differentiation and stratification within societies, and made possible,

and indeed necessary, the "urban revolution" that was to follow within three or four millennia

in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

In the case of agriculture, necessity was not the mother of invention. It was huntergatherers who already had enough to eat that made the shift to farming. Permanent

homes and stockpiles of wild cereals gave them enough time and energy to

experiment with cultivating seeds and breeding animals without the risk of starvation.

As food was grown and stored more efficiently, populations increased and

settlements grew larger, creating both the incentive and the means to produce

even more food on more land.

Spread of

Agriculture

Agriculture spread at different rates, depending on climate and geography. From

the Fertile Crescent, it moved west through Europe and Egypt and east through

Iran and India, reaching the Atlantic Coast of Ireland and the Pacific Coast of

Japan by the beginning of the Christian era.

From its origins in China, agriculture moved south, eventually spreading across

the Polynesian islands. In contrast, agriculture passed either slowly or not at all

through the tropical and desert climates surrounding early agricultural sites in

Egypt, sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and the Andes. Domesticated

animals did not reach South Africa until around A.D. 200, the same time corn

reached the eastern United States. It was therefore the plants, animals, and farmrelated technologies of the Fertile Crescent and China that had the greatest impact

on future civilizations.

Role of

technology

Iron

The hunter-gatherers of the Fertile Crescent and China had been making tools

from stone, wood, bone, and woven grass for thousands of years. Once farming

took hold, people improved their tools so

they could plant, harvest, and store crops

more efficiently. One of the earliest tools was

a pointed digging stick, used to scratch

furrows into the soil. Eventually handles were

attached to make a simple plow (see picture

right), sometimes known as an ard. Around

3000 B.C. Sumerian farmers yoked oxen to

plows, wagons, and sledges, a practice that

spread through Asia, India, Egypt, and

Europe.

After iron metallurgy was invented in the Fertile Crescent around 900 B.C., iron

tips and blades were added to farming implements. The combination of irontipped plows and animals to pull them opened previously unusable land to

cultivation. Although seeds were most often simply thrown into furrows, some

farmers in Egypt and Babylonia dropped seeds through a funnel attached to the

end of the plow. The seeds were then trampled into the ground by a person or a

herd of sheep or pigs. Grains were harvested with wooden-handled sickles, with

either stone or iron blades.

Much time elapsed between the development of agriculture and the rise of

civilization in the Middle East and many other places. The successful agricultural

communities that formed were based primarily on very localized production,

which normally sustained a population despite recurrent disasters caused by bad

weather or harvest problems. Localized agriculture did not consistently yield the

kind of surplus that would allow specializations among the population, and

therefore it could not generate civilization.

77

Why

Agriculture?

There was nothing natural or inevitable about the development of agriculture.

Because cultivation of plants requires more labor than hunting and gathering, we

can assume that Stone Age humans gave up their former ways of life reluctantly

and slowly. In fact, peoples such as the Bushmen of Southwest Africa still follow

them today. But between about 8000 and 3500 B.C., increasing numbers of

humans shifted to dependence on cultivated crops and domesticated animals for

their subsistence. By about 7000 B.C., their tools and skills had advanced

sufficiently for cultivating peoples to support towns with over one thousand

people, such as Jericho in the

valley of the Jordan River and

Catal Huyuk in present-day

Turkey. By 3500 B.C.,

agricultural peoples in the

Middle East could support

sufficient numbers of noncultivating specialists to give

rise to the first civilizations.

As this pattern spread to or

developed independently in

other centers across the globe,

the character of most human

lives and the history of the

species as a whole were

fundamentally transformed.

The greater labor involved in

cultivation and the fact that it did not at first greatly enhance the peoples' security

or living standards caused many bands to stay with long-tested subsistence

strategies. Through most of the Neolithic period, sedentary agricultural

communities coexisted with more numerous bands of hunters and gatherers,

migratory cultivators, and hunters and fishers. Even after sedentary agriculture

became the basis for the livelihood of the majority of humans, hunters and

gatherers and shifting cultivators held out in many areas of the globe. For

example, due to the absence of the horse and most herd animals in the Americas,

nomadic hunting cultures became the main alternatives there.

Results of

agriculture

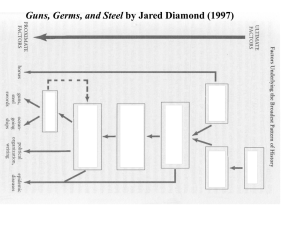

In transforming H. sapiens from a mere consumer of natural goods into a

producer, the development of agriculture drastically changed the role of humanity

within its environment, and thus the very nature of humankind. Moreover, it

permitted a vast transformation of human life and activity, involving both a

demographic increase and the rise of more complex human settlements and

communities. Agriculture required an increasingly greater specialization

differentiation and stratification within societies, and made possible, and indeed

necessary, the "urban revolution" that was to follow within three or four millennia

in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

78

One reason that civilization first appeared in the Middle East was because

agriculture had taken hold in this region. The river valleys provided people with

fertile soil due to their floods. These floods, combined with the new-found

knowledge of farming and animal domestication, allowed for a stable food supply

and so the Neolithic people settled down

around these rivers.

But localized agriculture did not

consistently yield the kind of surplus that

would allow specializations among the

population, and therefore it could not

generate civilization. Even the formation

of small regional centers, such as Jericho or

Catal Huyuk, did not assure a rapid pace of

change. Their economic range remained

localized, with little trade or specialization.

It was important that more and more regions in the Middle East were pulled into

the orbit of agriculture as the Neolithic revolution gained ground.

Social

Organization

The needs of irrigation, plus protection from marauders, help explain why most

early agricultural peoples settled in village communities, rather than isolated

farms. Some big rivers encouraged elaborate irrigation projects that could

channel water, virtually assured quantities to vast stretches of land. To create

larger irrigation projects along major rivers such as Tigris-Euphrates or the Nile,

large gangs of laborers had to be assembled. This required some sort of central

authority. Further, regulations had to assure that users along the river and in the

villages near the river's source would have equal access to the water supply. This

implied an increase in the scale of political and economic organization. A key

link between the advantages of irrigation and the gradual emergence of

civilization was that irrigated land produced surpluses with greater certainty and

required new kinds of organization.

Social

Stratification

79

The problems of these new, complex societies were many and varied: Dramatic

increases in population with pressing demands on housing and food supply;

disputes flaring up regularly due to the close proximity of families to each other;

crime and threats from both within and without, made strong leadership and

organizational skills absolutely necessary to the survival of a community. A new

political class emerged, specializing in the skills of governance. These people

were in a position to enforce laws, punish law-breakers, rule over internal

disputes, fight wars, and commission public works. They surrounded themselves

with close groups of advisors and experts to help maintain their position of

privilege. They raised finance for their endeavors by demanding tribute, or taxes,

from their subjects. Myths were often invented to guarantee their exalted position

over many generations. The art of kingship was born.

Property

Settled agriculture, as opposed to slash-and-burn varieties, usually implied some

forms of property so that land could be identified as belonging to a family, a

village, or a landlord. Only with property was there incentive to introduce

improvements, such as wells or irrigation measures that could be monopolized by

those who created them or left to their heirs. But property meant the need for new

kinds of laws and enforcement mechanisms, which in turn implied more

extensive government. Here agriculture could create some possibilities for trade

and could spur innovation.

Security

All this wealth, prosperity, and stability had a downside. There were lots of

people around who greatly coveted it and would stop at nothing to get hold of it.

New security measures were required to keep unwanted people away from other

peoples' possessions. Barriers and walls were constructed, leading in time to forts

and citadels. Yet another group of specialists, soldiers, emerged, either to defend

the property of the rich, or to attack others in order to achieve greater enrichment.

Rules governing the rights of property ownership had to be devised and enforced,

leading much later to the legal system.

Disease

Division of

Labor

The new sedentary lifestyle brought with it an unprecedented and enduring threat.

For the first time in history, large groups of humans, animals, waste material, and

rubbish were concentrated together in the same households. This close proximity

conferred advantages to select organisms that were quickly able to jump species,

infecting the human population in large numbers for the very first time. Examples

included smallpox, tuberculosis and measles, influenza and malaria. It was

around this time also that the rat attached itself to human societies and has

prospered ever since. Although medicine has played a major role in quelling

many diseases in modern society, many of them continue to kill millions of

people each year.

Another effect of the food surplus was that not

everybody needed to be involved almost solely in

the activity of finding and preparing food. People

now had more time to do other things and some

people were at liberty to dedicate themselves

entirely to other pursuits. New skilled professions

were born such as tool-making, milling (see picture

left), pottery, weaving, and carpentry, to name a few.

Thus, the Neolithic Revolution gave rise to rapid technological progress that

continues unabated to the present day.

80

Trade

Material

Culture

Population

Growth

Trade was always a feature of hunter-gatherer societies; however, with the

development of farming it increased greatly in scope and scale. With excess food

and newly created specialist crafts available, societies had a greater capacity to

produce goods of value to others. A new class of specialists emerged to facilitate

the exchange of goods: the merchants. In many cases these people became

enormously wealthy and powerful. Inequality had arrived, and a whole new set of

systems and structures would be required to deal with this.

This material culture includes products of human manufacture, such as

technology. This system is commonly known as an economy. Anthropologists

look at several aspects of people’s material culture. These include the methods by

which people obtain or produce food, known as a pattern of subsistence; the ways

in which people exchange goods and services; the kinds of technologies and other

objects people make and use; the effects of people’s economy on the natural

environment.

Contemporary industrial societies have organized markets for land, labor, and

money, and virtually everything is a commodity. People buy and sell goods and

services using money. This form of economy, known as capitalism, disconnects

the value of goods and services from the goods and services themselves and the

people who produce or provide them. Thus, the exchange of goods and services

for currency is not particularly important for creating social bonds.

In hunter-gatherer societies, women need a gap of at least three to four years

between children, as multiple, highly dependent babies are incompatible with a

mobile lifestyle. No such limitation existed when people lived in permanent

settlements, and so it became possible for women to have children much more

frequently. Additionally, as the techniques of plant cultivation and animal

husbandry became more refined, it was possible to feed entire groups of people

from relatively small numbers of food-sources, and still have food left over for

storage during the winter months. People in agricultural communities were less

subject to the whims of nature than hunter gatherers and thus had a higher chance

of survival. Thus, a population explosion occurred, and over time villages, then

towns, and eventually cities, took shape.

81

DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTION (DBQ)

A “turning point” is defined as a period in history when a significant change occurs.

Question: Using information from the documents and your knowledge of history, answer the following

question in one well-written paragraph.

“Explain why the Neolithic Revolution is considered a turning point in human history.”

Guidelines:

In your paragraph, be sure to:

• have a thesis statement that includes the restated question and three main points you will

use to support your thesis.

• cited all three sources using Chicago Advanced footnotes.

• use relevant outside information

• prove your thesis with relevant facts, examples, and details

• have a logical and clear plan of organization

Part A - Short-Answer Questions

Document 1

Bringing home the harvest: the origins of agriculture

The Economist, November 15, 1997

From World History in Context

COPYRIGHT 1997 Economist Intelligence Unit N.A. Incorporated.

http://store.eiu.com/

THE agricultural revolution of the Neolithic era, some 10,000 years ago, was the most important

event in human history. Before it, Homo sapiens was just another large mammal. A little more

omnivorous than most large mammals, it is true. Armed with a more sophisticated tool kit and

blessed with a more impressive means of communication than contemporary beasts of equivalent

size, but, in the essentials of making a living by finding and eating what nature provides, people

then were no different from lions or wolves or antelopes.

All that human civilization has produced in those ten intervening millennia is underpinned by

agriculture. The deliberate modification of ecosystems so that they will yield plants and animals

that mankind can eat (and also use in other ways) has caused a hundred-fold increase in the

82

human population and allowed large numbers of individuals to specialize in tasks not directly

related to feeding themselves. That it happened first in the broad area now called the Middle East

has been known for decades. But the Middle East is a big place, and the spotlight has darted all

over it as older and older sites showing evidence of agriculture have been turned up by the

archaeologist's trowel. Nor is it clear just how rapidly the revolution happened. Some researchers

believe that different plants and animals were domesticated at different times and in different

places, and that the final mixture was assembled by cross-cultural exchange. Others think that it

truly was a revolution, brought about over a short period by a small group of people and then

exported more or less intact to the rest of the region and, ultimately, the world.

Those who subscribe to the short, sharp shock theory of agriculture point to what is now southeastern Turkey as the place where it probably occurred. Two things support their idea. The

earliest known agricultural settlements are located here, and the area also supports-or, at least,

supported-possible wild ancestors of pretty well every important Middle Eastern crop and

domesticated animal. However, neither piece of evidence is conclusive. For one thing, earlier

settlements could be lurking undiscovered elsewhere. For another, the same ancestral

populations are found, though not necessarily together, in other parts of the Middle East as well.

Although later superseded as a crop by modern "bread wheat" (a hybrid of einkorn and two other

wild species, known as goat grasses), einkorn was one of the most important crops of early

Middle Eastern agriculture-indeed, it is still cultivated in marginal habitats in the Balkan

peninsula where bread wheat will not grow. Crucially, wild einkorn-the presumptive ancestor of

the crop-also still grows plentifully in the Middle East.

The results built up by the researchers showed that all the strains of cultivated einkorn they

examined could be traced back to a single, common ancestor among the wild forms. This more

or less proves that the domestication of einkorn happened only once, and thus strengthens the

case that the agricultural revolution started as a local event. They also showed that this common

ancestor was the ancestor of 11 strains of wild einkorn from the Karacadag Mountains, but of no

other wild strains (except for a few from the Balkans that are feral versions of domesticated

einkorn).

This is an exciting discovery, for the very oldest known archaeological sites that show evidence

of agriculture are not merely in south-eastern Turkey; they are located within a few kilometers of

the Karacadag Mountains. The team's work suggests that these sites really are the earliest

evidence of agriculture, rather than merely the earliest that archaeologists have yet discovered. It

also suggests that the people who built them were the most important inventors in history.

Directions: Analyze the documents and answer the short-answer questions that follow each

document in the space provided

1.___________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

2.___________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

83

Document 2:

Neolithic Revolution

by Jeffery Watkins

Copyright © 1999-2003 Oswego City School District Regents Exam Prep Center

During the Paleolithic Period, which lasts from the beginnings of human life until about 10,000

BCE, people were nomads. They lived in groups of 20 -30, and spent most of their time hunting

and gathering. In these groups, work was divided between men and women, with the men

hunting game animals, and women gathering fruits, berries, and other edibles. These early

peoples developed simple tools such as, spears and axes made from bone, wood, and

stone. Human beings lived in this manner from earliest times until about 10,000 BCE, when

they started to cultivate crops and domesticate animals. This is known as the Neolithic

Revolution.

The Neolithic Revolution was a fundamental change in the way people lived. The shift from

hunting & gathering to agriculture led to permanent settlements, and the establishment of a

traditional economy. A traditional economy is generally based on agriculture, with others in

society working in simple crafts, such as the manufacturing of cloth or pottery.

About 10,000 BCE, humans began to cultivate crops and domesticate certain animals. This was

a change from the system of hunting and gathering that had sustained humans from earliest

times. As a result, permanent settlements were established. Neolithic villages continued to

divide work between men and women. However, women's status declined as men took the lead

in in most areas of these early societies.

The economic factor of scarcity influenced early village life in the areas of government and

social classes structure. Wars caused by scarcity were frequent. During these wars, some men

gained stature as great warriors. This usually transferred over to village life with these warriors

becoming the leaders in society. Early social class divisions developed as a result. A person's

social class was usually determined by the work they did, such as farmer, craftsman, priest, and

warrior. Depending on the society, priests and warriors were usually at the top, with farmers and

craftsman at the bottom.

New technologies developed in response to the need for better tools and weapons to go along

with the new way of living. Neolithic farmers created a simple calendar to keep track of planting

and harvesting. They also developed simple metal tools such as plows, to help with their

work. Some groups even may have used animals to pull these plows, again making work

easier. Metal weapons were developed as villages needed to protect their valuable resources

Name three changes that occurred because of the Neolithic Revolution.

1.____________________________________________________________________________

2.____________________________________________________________________________

3.____________________________________________________________________________

Add any additional information you think is helpful

_____________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

84

Document 3:

Origins of Agriculture

Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, 2003 From World History in Context

The last thirty years have seen a revolution in our understanding of the origins of agriculture.

What was once seen as a pattern of unilateral human exploitation of domesticated crops and

animals has now been described as a pattern of coevolution and mutual domestication between

human beings and their various domesticates. What was once seen as a technological

breakthrough, a new concept, or "invention" (the so-called Neolithic revolution) is now

commonly viewed as the adoption of techniques and ultimately an economy long known to

foragers in which "invention" played little or no role. Since many domesticates are plants that in

the wild naturally accumulate around human habitation and garbage, and thrive in disturbed

habitats, it seems very likely that the awareness of their growth patterns and the concepts of

planting and tending would have been clear to any observant forager; thus, the techniques were

not "new." They simply waited use, not discovery. In fact, the concept of domestication may

have been practiced first on nonfood crops such as the bottle gourd or other crops chosen for

their utility long before the domestication of food plants and the ultimate adoption of food

economies based on domesticates (farming).

The question then becomes not how domestication was "invented" but why it was adopted. What

was once assumed to depend on cultural diffusion of ideas and/or crops is now seen by most

scholars as processes of independent local adoption of various crops.

The domestication of the various crops was geographically a very widespread series of parallel

events. Some scholars now recognize from seven to twelve independent or "pristine" centers in

which agriculture was undertaken prior to the diffusion of other crops or crop complexes

(although many of these are disputed) scattered throughout Southwest, South, Southeast, and

East Asia; North Africa and New Guinea; North, Central, and South America; and possibly

North America. As the earliest dates for the first appearance of cultigens are pushed back; as

individual "centers" of domestication are found to contain more than one "hearth" where

cultivation of different crops first occurred; as different strains of a crop, for example, maize or

rice, are found to have been domesticated independently in two or more regions; as an increasing

range of crops are studied; and, as little-known local domestic crops are identified in various

regions in periods before major crops were disseminated, the number of possible independent or

"pristine" centers of domestication is increasing, and the increase seems likely to continue.

Domestication (genetic manipulation of plants) and the adoption of agricultural economies

(primary dependence on domestics as food), once seen as an "event," are now viewed as distinct

from one another, each a long process in its own right. There is often a substantial time lag

between incipient domestication of a crop and actual dependence on it. That is, the adoption of

farming was a gradual quantitative process more than a revolutionary rapid adoption—a pattern

of gradually increasing interaction, and degrees of domestication and economic interdependence.

Moreover, the adoption of agriculture was, by all accounts, the coalescence of a long, gradual

series of distinctive and often independent behaviors. Techniques used by hunter-gatherers to

85

increase food supplies, long before farming, included the use of fire to stimulate new growth; the

protection of favorite plants; sowing seeds or parts of tubers without domestication; preparing

soils; eliminating competitors; fertilizing; irrigating; concentration of plants; controlling of

growth cycles; expansion of ranges; and ultimately domestication. By this definition,

domestication means altering plants genetically to live in proximity to human settlements,

enlarging desired parts, breeding out toxins, unpleasant tastes, and physical barriers to

exploitation—in short, getting plants to respond to human rather than natural selection.

This sequence of events commonly first involved a focus on a shift from economies focused on

comparatively scarce but otherwise valuable large animals and high-quality vegetable resources

to one in which new resources or different emphases included smaller game, greater reliance on

fish and shellfish, and a focus on low-quality starchy seeds. There is a clear and widespread

appearance of an increase in apparatus (grindstones for processing small seeds, fishing

equipment, small projectile points) in most parts of the world before agriculture, Agriculture,

therefore, may not have been "invented" so much as adopted and dropped repeatedly as a

consequence of the availability or scarcity of higher-ranked resources. This pattern may in fact

be visible among Natufian, or Mesolithic, populations in the Middle East whose patterns of

exploitation sometimes appear to defy any attempt to recognize, naively, a simple sequence of

the type described above.

Domestication, sedentism, and storage appear to have evened out potential seasonal shortages in

resources, but they may also have reduced the reliability of the food supply by decreasing the

variety of foods consumed; by preventing groups from moving in response to shortages; by

creating new vulnerability of plants selected for human rather than natural needs; by moving

resources beyond their natural habitats to which they are adapted for survival; and by the

increase in post-harvest food loss through storage—not only because stored resources are

vulnerable to rot, or theft by animals, but stores are subject to expropriation by human enemies.

One possible biological clue to the resolution of this problem is that signs of episodic stress

(enamel hypoplasia and microdefects in teeth in skeletal populations) generally become more

common after agriculture was adopted. Since health and nutrition seem to have declined, the

primary advantage to farmers seems to have been both political and military because of the

ability to concentrate population and raise larger armies. This would have conferred a

considerable advantage in power at a time when few if any weapons were available that were

capable of offsetting numerical superiority.

Based on this document, identify two important facts about the Neolithic Revolution.

1.____________________________________________________________________________

2.____________________________________________________________________________

Add additional information which you think is important

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

86

Essential Questions

Answer these questions using information from manual, notes, etc. to be answered before DBQ.

What defines a turning point?

To what extent is life a constant struggle between continuity and change?

How does technological change affect people, places, and regions?

Focus Questions for thinking about your essay

Why is the Neolithic Revolution considered a turning point in human history?

What was the relationship between the Neolithic Revolution and the development of

early civilizations?

87

What led to the rise of cities?

What political systems developed in early civilizations?

What is a traditional economy?

Part B – Open response

This writing is based on the accompanying documents (1–3). The question is designed to test

your ability to work with historical documents. As you analyze the documents, take into account

the source of each document and any point of view that may be presented in the document. You

must cite each article using footnotes set up on Noodletools Use Chicago Advanced.

Open Response:

Thesis (DBQ question restated + 3 main points)

___________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Main point #1 __________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Support for main point #1

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Main point #2 _________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Support for main point #2

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

88

Main point #3 _________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Support for main point #3

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

Conclusion (reverse and restate thesis)

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________

89

Grading Criteria Sheet

Excellent Essay 90’s

• Offers a clear answer or thesis explicitly addressing all aspects of the essay question.

• Does a careful job of interpreting many or most of the documents and relating them

clearly to the thesis and the DBQ. Deals with conflicting documents effectively.

• Uses details and examples effectively to support the thesis and other main ideas.

Explains the significance of those details and examples well.

• Uses background knowledge and the documents in a balanced way.

• Is well written; clear transitions make the essay easy to follow from point to point.

Good Essay 80’s

• Offers a reasonable thesis addressing the essential points of the essay question.

• Adequately interprets at least some of the documents and relates them to the thesis and

the DBQ.

• Usually relates details and examples meaningfully to the thesis or other main ideas.

• Includes some relevant background knowledge.

• May have some writing errors or errors of fact, as long as these do not invalidate the

essay’s overall argument or point of view.

Fair Essay 70’s

• Offers at least a partly developed thesis addressing the essay question.

• Adequately interprets at least a few of the documents.

• Relates only a few of the details and examples to the thesis or other main ideas.

• Includes some background knowledge.

• Has several writing errors or errors of fact that make it harder to understand the essay’s

overall argument or point of view.

Poor Essay 60’s

• Offers no clear thesis or answer addressing the DBQ.

• Uses few documents effectively other than referring to them in “laundry list” style, with no

meaningful relationship to a thesis or any main point.

• Uses details and examples unrelated to the thesis or other main ideas. Does not explain

the significance of these details and examples.

• Is not clearly written, with some major writing errors or errors of fact.

Failure to meet the most of the criteria above will result in a 55.

90

Works Consulted

Agriculture. Cristiano Grottanelli. Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay

ones. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. P185194. (9567 words) From Gale Virtual Reference Library.

“Agricultural Revolution: China 6000 BC”. Pearl Of the Orient. 14 March 2000. University of

Alberta. 13 March 2008 http://www.ualberta.ca/~vmitchel/rev2.html.

“command economy” InvestorWords.com. Web Finance, Inc. June 15, 2008

http://www.investorwords.com/951/command_ec

“The Domestic Revolution.” Ideaworks, Inc. 10 July 1995. University of Missouri. 13 March

2008< http://web.missouri.edu/~brente/domrev.htm>.

Elsworth, Stephany. "What Is the Younger Dryas?" e-How. Demand Media Inc.,

2014. Web. 28 Mar. 2014. <http://www.ehow.com/ acts_7860099_younger-dryas.html>.

Evans, Lindsay. “Early Agriculture and the Rise of Civilization.” Science and Its Times. Ed. Neil

Schlager and Josh Lauer. Vol. 1: 2,000 B.C. to A.D. 699. Detroit: Gale, 2001. 309-312.

Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 21 Oct. 2010.

Fitzgerald, Richard D. “Water Management in the Ancient World.” Science and Its Times.

Ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer. Vol. 1: 2,000 B.C. to A.D. 699. Detroit: Gale, 2001.

332-334. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 21 Oct. 2010.

Hunter, Erica. First Civilizations. New York: Facts on File, 1994.

Mazour, Anatole G. and John M. Peoples. World History: Peoples and Nations. United States:

Harcourt Brace Javanovich, 1993

“The Middle East By 4000 B.C.: The Causes Of Civilization.” World History From The

Pre-Sumerian Period To The Present. 2007.International World History Project.

3April 2008< http://history-world.org/neolothic2.htm>.

“The Neolithic Revolution – How Farming Changed the World.” The Guide to Life, the

Universe, and Everything. 5 March 2004. BBC. 13March 2008

http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2054675.

“Origins of Civilization.” A Project by World History International. Copyright © 1995 –

2006[World History Project, USA] All rights reserved. Updated January

2007*http://history-world.org/22eolithic.htm

Schultz, Emily A, and Robert H. Lavenda. “The Consequences of Domesticatio and

Sedentism.” Primitivism. N.p., 3 Nov. 2002. Web. 22 Dec. 2009.

Scullin, Michael. "What Is Horticulture." Archaeology. About.com, 2014. Web. 28

Mar. 2014. <http://archaeology.about.com/od/hterms/g/ horticulture.htm>.

91