The Cuban Missile Crisis as Framed by the Media

advertisement

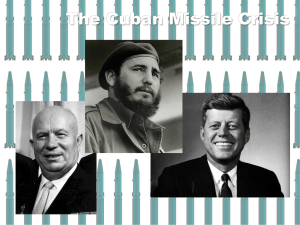

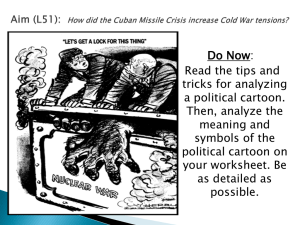

THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 1 The Cuban Missile Crisis as Framed by the Media Emily Jensen University of North Florida The Cuban Missile Crisis as Framed by the Media THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 2 For 16 days in October of 1962 the Cold War was anything but cold. President Kennedy was shown several photographs on October 16th proving that the Soviet Union was installing defense missiles in Cuba. Soviet diplomats denied the missiles and on October 22nd President Kennedy made a televised announcement to the American people about the finding of the missiles. There was much debate about how to handle the situation. Some U.S. officials wanted to invade Cuba but President Kennedy chose a different way to handle the situation; he set up a quarantine around Cuba. The United States Armed Forces were to stop offensive material from getting to Cuba by sea. The blockade was known as Proclamation 3504 and it was effective from October 24th to November 20th of the following year. The Cuban Missile Crisis is known as being a ‘crisis’ because Americans believed they were ahead of the Soviet Union’s time. The United States had missiles in Turkey that were capable of reaching the Soviet Union, whereas their missiles were not capable of reaching the U.S. This was comforting to Americans. So it came as a shock to the U.S when Soviet diplomats decided to move their missiles to Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis was the closest the U.S. and the Soviet Union came to a confrontation during the Cold War. It was the responsibility of the press to keep the people informed about the crisis. The media framed Cuban and Soviet THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 3 Union officials as evil, wrong-doing people who would not cooperate with U.S. officials. They framed the United States as having heroic diplomats and being in great danger. The press also framed the event as of major importance by having large headlines, several stories per issue, and many photographs. The press portrayed the Cuban Missile Crisis as just that - a crisis. In “Castro is Defiant; Bars Arms Check” (1962) the Associated Press depicts the United States as being in severe danger. AP stated the Soviet Union sent a “serious warning” (p. 23) to the U.S. The article also mentioned the Cuban president was wearing a military uniform meaning he was ready to fight. Reporter Foster Hailey of the New York Times wrote “Steps are Taken by the Air Force” (1962) and said a security blackout was strictly enforced resembling the ones for World War II. Hailey (1962) also took note on how places around the U.S. and their alliances were taking precautionary actions and were ready to fight if needed. Even places far from Cuba, such as Hawaii, were prepared for rapid deployment (p. 22). The Cuban Missile Crisis seemed more like a crisis because of the way the press was framing it. The American people realized the danger at hand because of the wording of the media. For example, “this is an act that very soon will have repercussions in all nations” (“Castro Defiant”, 1962, p. 23) sounds more frightening than simply THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 4 saying Premier Castro disliked the blockade. Using Castro’s exact quote leaves a chilling thought in readers’ minds. The press does an exceptional job of displaying U.S. officials as being heroic and for the people. Cuban and Soviet Union diplomats are portrayed as immoral people. The President persuaded Americans of this in his speech given on October 22nd. He called placing the missiles in Cuba as being “provocative and unjustified” (“Text of the President’s Speech”, 1962, p. 18). Kennedy also insisted he was making the right choice on how to handle the situation. He said the goal was not victory, but rather “the vindication of right” (“Text of the President’s Speech”, 1962, p. 18). It is this type of wording that places the U.S. in a positive light and Communists in a negative one. In “Blockade Begins at 10 a.m. Today” (1962), the special correspondent used strong words such as ‘declared’ to make the U.S. seem powerful in its actions. This article clearly stated that it was the Soviet Union’s fault for the crisis by saying the President “put responsibility for the crisis - and thus the blockade directly on the Soviet Union” (p. 21). U.S. officials are put into the frame of the ‘good guy’. The article also depicted Cuba and the Soviet Union as being the rebels, having mentioned the blockade was approved 19 to 0. This also implied that the U.S. was taking the correct measures in terminating the issue. THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 5 Not only did the press frame Cuba and the Soviet Union as being wrong, they also portrayed them as not cooperating with what U.S. officials were telling them to do. “U.S. vs. Russia” (1962) said the only way Khrushchev would listen was by “hitting him over the snout” (p. 1). A White House aide interviewed for the article said he thought Khrushchev had not gotten their message due to the Soviet Union not paying little attention to the threats made by U.S. officials. In addition, “U.S. vs. Russia” made the Cuban Missile Crisis seem like no big deal. This is unlike the majority of news articles, besides opinion pieces, by saying “the Soviets already has missiles on its own soil which could do the job” (“U.S. vs. Russia”, 1962, p.1). The Wall Street Journal considered the crisis to be a good thing. Being a newspaper whose primary focus is business, the point that war stimulates the economy was made. This could be why they thought the crisis was not as bad as everyone else thought. “Almost every Federal fiscal and budgetary problem might suddenly turn inside out” (“U.S. vs. Russia”, 1962, p. 18). There was talk around Washington D.C. about a tax cut to stimulate the economy but the reporter seemed to think that the Cuban Missile Crisis would do the trick. The editors of The Wall Street Journal ran “If Cuban Invasion is Eventually Launched; Terrain Easy, but Castro Army Well-Armed” on page 18 about how effortless it would be to successfully invade Cuba. Ed Cony, the reporter, wrote THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 6 that “Havana would be a plum worth picking” and the island was “soft picking” (p. 18). They framed it as if there had been an invasion, the economy would have been in even better shape. Many of the articles in The London Times had the same views as American newspapers. England was one of the United States’ allies so it is not surprising that the views were similar. They framed the President as a hero and a man of his word by saying things such as he was “statesmanlike”. They agreed with his contribution to peace and applauded his “firm commitments” to ending the Cuban Missile Crisis (“Russia to Withdraw”, 1962, p. 10). England and the United States had similar views of Soviet diplomats as well. The article mentioned that most people were skeptical about Khrushchev’s consent to remove the missiles. They too, believed Cuba and the Soviet Union were wicked for their actions. The London Times framed Castro as a weak leader who had the “humiliating role” of dismantling the missiles and was dependent upon communist countries for supplies (“Castro Demand”, 1962, p. 10). They outlined the communist party as having a lack of communication because Castro radioed a message to the U.S. about the conditions under which he would remove the missiles even though Khrushchev had already agreed to take them down. Adding this to the article made communists seem like fools. THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 7 Time.com published an article on the 20th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis in which U.S. officials who played key roles talked about lessons learned. Surprisingly, they showed Khrushchev as a statesmanlike person and admired his change of mind. This is opposite from the views in 1962. One view that remained the same is how sensible President Kennedy was to the situation. “In the successful resolution of the crisis, restraint was as important as strength” (“The Lessons Learned of the Cuban Missile Crisis”, 1982). The movie Thirteen Days gave an inside prospective of White House officials during the nerve racking days of October 1962. As compared to the press, the movie portrays the military as being the decision makers as opposed to the President. Kennedy, however, was under the impression that the military wanted redemption for the Bay of Pigs incident. It is because of this that he took full control of the blockade; all armed forces were under his command. Kennedy’s administration, according to Thirteen Days, urged the press not to write about the military preparations prior to his speech on October 22 nd. “They (the press) will be saving lives, including their own” (“Thirteen Days”, 2000). Also, U.S. officials refused to tell the press why there was excessive military exercises before the president made his speech. Not even the White House correspondent knew what happening. THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 8 News first broke to the public of the Cuban Missile Crisis after President Kennedy made a broadcast announcement. If it were not for television and radio, word of the crisis would have taken longer to circulate. The media played the major role of keeping the public up to date during this time. The media faced prior restraint and really had to dig for their information. Nevertheless, the press was still capable of having several articles and photographs in each issue. This made the Cuban Missile Crisis seem like the most important topic during that time. Kennedy’s administration enforced prior restraint on the press because they were afraid of the damages it might cause. Because of this, the media were more like story tellers. They could only tell the information that was already public. Running several articles put the event into prospective for people. As opposed to having just one large article, having multiple small ones with large headlines made it not only seem important, but also clearer to the readers. It was because of the Cuban Missile Crisis that the Hot Line was created. This was a way for the two countries to communicate directly, eliminating the middle man. In a way, the White House did this with the press. The correspondent was the hot line. That way, there was no confusion. It is safe to say that because of this the media framed Soviets and Cubans as bad people, and framed the U.S. as doing the right thing. The U.S. truly was in danger during this time and that is exactly how the media portrayed it. THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 9 References Castro Demand for Return of Guantanamo. (1962, October 29). The London Times, p. 10. Castro is Defiant; Bars Arms Check. (1962, October 23). The New York Times, pp. 1, 23. Cony, E. (1962, October 23). If Cuban Invasion is Eventually Launched: Terrain Easy, but Castro Army Well-Armed. The Wall Street Journal, p. 18. Cuban Missile Crisis. (n.d.). In Global Security. Retrieved September 27, 2010, from U.S. Cavalry website: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/cuba-62.htm Essay: The Lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis. (1982, September 27). Time. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,925769,00.html Greenwood, B., Culp, S., & Costner, K. (2000). Thirteen Days. Infinifilm Hailey, F. (1962, October 23). Steps are Taken by the Air Force. The New York Time, p. 22. Kenworthy, E. W. (1962, October 23). Blockade Begins at 10 a.m. Today. The New York Times, pp. 1, 17. Russia to Withdraw Missiles from Cuba. (1962, October 29). The London Times, p. 10. THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS 10 Text of the President's Speech on Arms Blockade of Cuba. (1962, October 23). The Wall Street Journal, p. 18. U.S. vs. Russia. (1962, October 23). The Wall Street Journal, pp. 1, 18.