One day she swam out to sea. The water was

advertisement

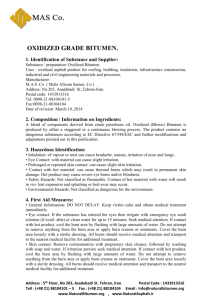

Cover: Using different voices, Liquid Selves explores a body of work made by dripping bitumen onto canvas. Through the different texts (the ëpersonalí, the ëtheoreticí and the ëpoeticí) Delpha Hudson explores the fragmentary and multiple nature of self, selfhood and gender, and how these might be discursively understood as her art practice.Page 1 Writing in 3 voices Since 2007 I have been dripping bitumen instead of painting, creating a ëliquid aestheticí. Dripping bitumen onto white gessoed canvases, figures, patterns, and partial narratives, began to emerge. The suspension of ordinary rules of painting and the potential to depict a fantasy of self led to a visual imagery of many ëtypes,í (archetypes, rather than stereotypes) constructed in time and space. These 'types' both somehow typified all women, and my own personal experiences. ëLiquid Selves' seemed an appropriate description of not just the medium which never entirely solidifies, but also for the subject of self, as never entirely fixed. In order to understand and interpret the work, I began researching and writing about the process; the words like the images were split like subjectivity into many voices. Three main voices emerged which could be described as ëthe theoreticalí, ëthe personalí, and ëthe poeticí. I hope the text in some way reflects the perpetual conversation, and continual rumble that we all experience as we negotiate different 'voices', and who we think we are. Each of us are many continually transforming 'selves'. Page 4 Voice 1: the personal Hélène With my given name ëDelphaí I have always been fascinated by the classical tradition of self-knowledge, and the Delphic oracleís admonition ëknow thyselfí. Dripping bitumen onto canvases has become a performance and dream of self, a personal reflection on selfhood and identity. In performance works exploring gender and female identity, I have endeavoured to use Braidottiís idea of ëdissonant voices moving between positions in a nomadic quest for alternative representation of female feminist subjectivityí. Playing with different subject positions, negotiating identity in different ways, often occurred by a ëslippageí between my performed self, and ëmeí (or ëherí). Written in Milk, (2001), and Written in Honey (2002) were both inspired by Helene Cixousí ëÈcriture feminineí, and Luce Irigarayís project of ëwriting the body,í as both explored the textural and gestural properties of writing in different symbolic media. In Written in Milk, I covered white linen spread on the floor of an exhibition space (approx 150mx40metres), in ëautomatic writingí written in milk. Taking a whole day, the writing became a fatty residue, leaving barely legible traces. It created a sickly smell that permeated the space. The object was not the writing itself, but a process and performance of writing myself. The linen was washed and re-used for bedding. Page 5 In Written in Honey, I created huge window handings for a Tudor house at Helmsley in Yorkshire. Using locally produced honey, I coveed the translucent cloth with historical images and narratives (some fabricated by myself). The marks created by dripping honey were invisible until held up to the light. A metaphor for the invisiblity of women, especially in histories written by men, the hangings were made to evidence the day-to-day lives of ordinary women. The process was a performance of combining image and text in sitespecific installation, created with the hope of somehow embodying gendered identities. Images left to right: Written in Milk, (2000) , Written in Honey, (2000), Pieces of Scarlet, (2001) Page 6 Fascinated by histories of text and image, Pieces of Scarlet (2000) was a performance in Birmingham city centre, in which pieces of red material wth symbols and letters were placed in 25 layers of white undergarments. These were removed layer by layer and the 'pieces of scarlet' handed out to the public. Both symbols and letters were historically believed to have magical properties if worn next to the skin. Often single alphabetical letters replaced symbols as people became literate. Wearing these texts next to the skin, and peeling them off layer by layer was a metaphor for the palimpsest of the self. A historical play with text, symbol, gift and gender as the white underwear attracted crowds, who would not always accept the mysterious gift of a piece of scarlet. but wondered how far the disavowal of clothing would go........ Writing and pattern making with bitumen has become a different kind of performance of gender and self. In fact, exploring identity itself. I want to explore what it means to be not only one woman, but many women. Liquid Selves are a process and performance of ëknowing myselvesí. p.7 Voice 2 the theoretical In Feminist thought the project of unfixing identity is important to dispelling myths about sex and gender stereotypes. Identity is ëperformedí by the subject, enacted and negotiated through social and cultural roles. Gender is constructed, not biologically determined. The performance of identity for women has been one of the performance of ëfemininityí, weighted with expectation and confined to stereotypes. The notion of ëfixed identityí remains a founding stone of Western society and thought. It supports an ordering of society in which everyone is fixed, and should not exceed their position. Feminist theorists Simone De Beauvoir, Helene Cixous, and Luce Irigaray have used theories of embodied and sexually differentiated subjectivity to invent ways of overcoming fixity, loosening the ties between gender, sex, essentialism, and difference through new kinds of writing. Their writing about sexual difference tampers with theoretical constructs. Re-interpreting the psycho-social development of a child based around its body and conditioning, examines the tension and struggle between circumstances and individuation. Writing of sexual difference goes beyond the material and social factors affecting self. One of the shrouds of conditioning is the conformity of belief that as individuals we have only one ëselfí, one identity. This is the ëdream of unity,í a myth of a unitary ëIí that must be shattered in order to re-negotiate gendered subjectivity. p.8 ‘I’ p9:Voice 2 the theoretical ë Ö a man is defined as a being who is not given, who makes himself what he is. As Merleau-Ponty very justly puts it, man is not a natural species, he is an historical idea. Woman is not a fixed reality, but rather a becomingí. Here Simone De Beauvoir unfixes the stereotype of woman with the concept of ëbecoming womaní. Exceeding traditional notions of identity and subjectivity, opens a crack in discourse which acknowledges the possibility of liberating multiplicities, and fragmenting single representations of female stereotypes. ëBecomingí infers a continual process, it cannot be fixed. Feminist theory incites the ëIí to a new relation with herself, others and symbolic order,í and allows the transformation of the structure and images of thought. In this flux, the individual faces contradictions whatever s/he does, whoever s/he believes herself to be, negotiating identity and subjectivity, through ëplurality, overlap, and manoeuvreí . Discovering s/he has a freedom to use nomadic contingency, and gently nudge ideas that proffer alternative modes of being, and alternative ways of representing self and gender, the idea of identity becomes a discursive premise. p.10 me-you-her-it P11 The children loved the countryside They would run and hide They loved the seaside They would all play and ride The waves, until it was time to go back to the city. One day they went far way to a little village by the sea. Their great-grandpa (who always said ëbless my buttons!í) lived in a little cottage by the harbour. They loved jumping from the old stonewalls into the smooth green . Their mother seemed especially happy She sat for hours watching the bright water She loved the salt smell p.12 She felt at home with herself The children watched her and felt a little lonely. But they played their games and bought their treasures to her. p.13 voice: the personal I am transformed by the thought that I am, and can be many people. One of my many selves has been ëmotherí. My work has often focussed on the problematic of representing ëmotherí beyond stereotypes. Motherhood traditionally depends upon a performance of self-less mother-love, a cultural collusion in which the gendered self is completely negated for the love and good of the child. Although this is presumed to be a ënaturalí for women, when they become mothers, in reality the irony is that women need to appropriate new selves to succeed in this role. Discovering what Feminist art and theory had to say about this was for me ëwinning the right to mix and match stereotypes', I discovered like many women I could be a mother and retain my sanity and sense of self, and ërecoverÖfrom the degradation of being divided against myselfí. Using clothing and ritual in my first performance Man Created the Word in 1999, I worked through three characters, in what I thought of as a íritualized shedding of personaeí. These were all characters I felt I had encountered and performed. Wearing fishermensí yellow p.14 3 images man made he word overalls I presented a male figure, gutting fish, with power over living and dead things, as well as potentially a ëfisher of mení, Peeling off the waterproofs revealed a manís pinstriped suit, in which I typed and read from the bible: ëSo God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him;Ö and the word, the word was with Godí. I wanted to present the moment in history where men took credit for creation, and control of language. I wanted to intervene and bare the irony. Peeling off the suit revealed a wedding dress. Putting on high heels and an apron, I crafted a baby out of lard. A messy, smelly performance which revealing bitterness at societies that give lip service to women for the role they play in creating life and mothering, whilst real power, through the control of word and image, remains in the hands of men. p15 Speaking, or representing difference in order to play with semiotic apparatus of traditional images, symbolisation and the symbolic, can change how we think and what we think Dr Ryya Bread writing for her PhD at Falmouth in 2001, explored visual material representation and how it operates within the linguistic realm of symbolic order in the formation of subjectivity. Image and materiality have a specific position to each other, and can embody, and create differing signifying values with regard to representation of a subject. Cixousís project of ëwriting differenceí could also be a project for creating difference using image, symbols as well as the written word. An ancient symbol, the mermaid has an interesting history of change and in many ways is a ëtypeí for how women are viewed at anytime in history. An ancient symbol of power and fertility the mermaid became a symbol of vanity and evil from the 17th century, with her comb and mirror. The stories about her start to change and she becomes an evil siren destroying men. Victorian Pre-Raphelites presented the mermaid as a lascivious maneater. p.16 and sexual humour in films were later presented in films such as ëMirandaí [1948], ëThe Little Mermaidí [1989], and ëSplashí, [1990]. By the end of the 20th century, the mermaid symbol used for breast cancer awareness by the Mermaid Trust, presents a less sexualized female symbol, with potential to re-structure assumptions through re-representation and change. Like language, the power of image and symbol has been used through out history to control and equally to subvert thought. Ancient and Communist China consistently used beautiful and poetic symbols to control the thinking of huge populations. The same is true in the West as advertising appropriates image and symbols, changing their meaning almost daily, creating a situation in which theorists conclude such ësignsí become meaningless. Artists use such materials in an almost ëdiabolicí way subverting the uses of symbols and images in personal and poetic ways. p.17 HER-ME p18 One day she swam out to sea. The water was bright and fresh and green. All the way to the island, climbed up to the highest rock, then back to the waterís edgeÖ.. Lapping around her ankles, her legs grew together in the water. Her long, thin feet became fins. Now at one with the water she swam free A mermaid was what she was destined to be p.19 I-HERE (C/UPS) ME-YOU-IT I find myself drawn towards viusal image and text, without using one to illustrate the other. Wanting to represent in some ways ideas. Endeavouring to find a language that nudges and pulls the person standing in front of my work, into another world. A world of possibilitiy in which each one of us is many. P20 iquid Selves start with the premise that visual material representation is one way that we can explore unstable and unfixed identities, and in so doing represent gendered difference. I want my paintings to give a sense of being, so that a woman is aware of herselvesÖthat the on-looker knows that she is there. Chemically and textually I think of bitumen as a ëmotheryí or slime that from which we emerged. A birth of an idea, it is a reference to growth, change, and constant transformation. The instability of the medium means that it is never really fixed. I find an almost compulsive beauty in the way it stands out from the surface of the canvas, and in a smooth, glossy way ëgiv[es] tactile values to retinal impressionsí. Using sticks to drip bitumen onto surfaces is an almost ëautomaticí process as limited control means that whilst I am ëtransferringí ideas onto the surface of the canvas or board, the accidental dripping or ëblottingí, creates additional new forms. The chance drippings and droolings of the medium, create subconscious suggestions and like Cixous' metaphors for women as la mer/mËre (sea-mother), or a ëdark continentí. Bitumenís inky dark fluidity is unknowable, foreign and Other. Forms appear like phantoms. P21 Iamge P22, 23,24 The figures dripped in bitumen, energize the space around them, anthromorphizing traces, with nuances of narrative. These are ëtypesí, inviting audiences to internalize the figures and patterns as symbols in relationship to each other. Writing and text is made up of black and white patterns. In iquid Selves, the contrast of using only the dark bitumen on white gessoed canvas is like a metaphor for text and subjectivity, split between thought, and transformation. Interpretation is dependent on an ability to 'read' the figures and patterns. ëLanguage takes on a meaning for the child when it establishes a situation for him. A story is told in a childrensí book of the disappointment of a small boy who put on his grandmotherís spectacles and took her book in the expectation of being able himself to find the stories which she used to tell him. The tale ends with these words: ëWell, what a fraud! Whereís the story? I can see nothing but black and whiteí.(Merleau-Ponty in Toril Moi). Writing, drawing and painting is not a process of innocence and passivity, emptying the ëprospect of meaningí in order to re-fill it with another. The use of single or multiple figures encourages identification and the invention of narrative. The patterns are sometimes orderly and natural, at other times they are dreadful overgrown areas which impart a sense of skewed beauty. They are not Edenic scenes, beautiful in symmetry or regularity, they split the canvas into areas of chaos and emptiness. In this distorted nature characters emerge as inky clumsy marks to be transformed by interpretive frames. The process of applying bitumen with a stick uses chance, and happenstance, ëalmost as if the eye knows something of which the mind knows nothing.í The patterns and blank spaces in Liquid Selves do not seem like an imitation of nature. Pattern, image and text become ëiconographic utterance,Ö.the dream as a fiction constructed by a unique aesthetic; the transformation of the subject into [her] thoughts, specifically the placing of the self into an allegory of desire and dread that is fashioned by the egoí. 4 images: er children cried to her but all she could hear were the gulls She went on swimming Past Merlin Rock, Past Lamorna Cove, Past the fishing boats Beyond. The children were so sad.They tried to understand. They were left looking out to sea Saddest of all was their mother who looked but couldnít find what she was looking for She was at one with the sea, yet all alone. The children waited on the shore everyday, searching the horizon, waiting for their mother to return. Their mermaid-mother had many adventures. The dolphins made her heart fly The seals made her laugh The fish made her smile, But nothing made the ache in her heart disappear. I think of the process working with bitumen as positioning myself in language, perhaps even as part of Cixousís project of ëwriting differenceí. Bitumen pattern work appears almost like a ëtextí, an aesthetic form to transform thought, a beautiful language for ëbecomingí and knowing oneself. The use of multiple combinations of pronouns as titles for my drawings plays with the constraints of language. I donít want all these pronouns to slip by unnoticed, I want readers to think about and act on their conclusions. Working with pronouns, and visual language I negotiate meaning, discarding a dream of unity to find metaphors for difference, gender and representation. Depending on the temperature and viscosity of the bitumen, it ëspinsí like treacle off a spoon. The creation of the self, is made by ëspinning and being spun by storiesí. . We create ourselves by the stories and narratives that we select from our histories. Just as I have created myself from the constructs of my past, I create patterns as narratives of myself (selves) spun from bitumen. The process of chance and intention, plays with harmonies and dissonance that we find in our stories of ëselfí. My subjectivity is split as I transform the surface of the canvas. Forms ëgrowí around the figures, they seem like flowing natural forms, yet nature has gone wrong. They are sometimes delicate and often deformed. In some way the inclusion of forms and vegetation makes her become almost like an illustrated figure in a fairytale. I enjoy the possibility that these works could be interpreted as fairytales with dark, haunting possibilities. Instead of a Greek classical tradition of self-knowledge, and finding my authentic true self through old myths and narratives, I find myself creating new selves, exploring the ëenigmas of self, not-self, and otherí, and with the invitation to everyone to get to ëknow yourselvesí. Capitalized pronouns are combined and fused together as titles for Liquid Selves. They give no indication of the subject or hope of a narrative. As they are the part of language that fixes subject position, the use of pornouns seems to put in doubt the subject or ëwhoí of the work. De Beauvoir starts her classic The Second Sex with ëIí / ëjeí , a statement of existence, selfhood and the personal. In English ëIí is ëeyeí, writers have played with the intimation of the role of the visual in the understanding and representation of the self. Yet, ëIí is a fragment, a slippery word as it is always part of ëweí. Feminist strategies use language to play with and deconstruct gender. It is this ëIí, de-constructed and robbed of its historical specificity, that is used to question gendered identity, and explore the possibility of multiple selves, as the construction and maintenance of ìIí and ëselfí is only possible both with, and through others (you, they, weÖ..). The complexity of ëselfí, with its psychoanalytic theories of self, non-self and other, reveal problematic processes of ëbecomingí for women, yet remain a pre-condition for ëself-transformationí. The production and invention of personal narrative in forms around us, take us outside of ourselves, transporting us through identification to the time and place of another, aiding the ëtranscendence of the prison of the limitations of the selfí, Empathy, imitation, assimilation and projection produce shared dreams and fictions that have transformative potential. Narrative offers the interplay of multiple ideas, without offering a fixed position. The surface lines of the bitumen used in drawing become partial narratives, with the possibility of creating a frame or discussion about the fragmentation of ëselfí. Inserting and asserting the body into inert matter as signs, figures and space, can be a kind of transformation. Liquid Selves could be seen as a performance of selves, encouraging us to know ourselves, by creating,and re-creating ourselves. This is part of the process of ëbecomingí in which we have the potential to negotiate our reality through play. image References/ rather than a ísymbolicí way (according to the etymology of each of these words, ëdiabolicí corrupts and scatters, and ësymbolicí joins), List of images: p.12 NON-WE, (30x30cm), IT-ME, (30X25cm)