114-Holy Innocents - St. Eugene Catholic Church

advertisement

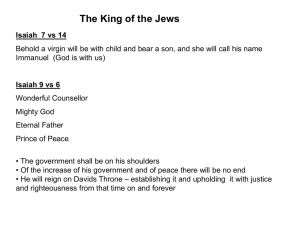

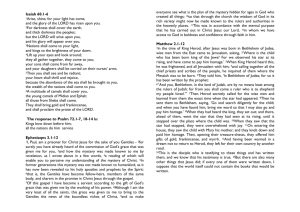

From the Amen Corner December 27, 2015 As we come to the end of the year there is a topic we should dwell on in this season. It is timely: yesterday was the Feast of the Holy Innocents. In a world full of suffering it is important to spend some time thinking about the place of innocents in our world. While suffering exists everywhere and at all times, it's safe to say we've entered a new awareness of the attack on innocence during this last year. Death and destruction seems to stalk our world. What we are to do as “this rude beast slouches toward Bethlehem” is the subject of the year to come. The Holy Innocents refer, of course, to the children who were slaughtered by the soldiers Herod sent in the wake of his encounter with the Three Kings. When the Magi came to Jerusalem asking for the birthplace of the newborn King of the Jews they went to Herod's court. Where else would a king be found but in a palace? These visitors told Herod they had noticed, three years previously, a star rising in the West and had followed it as far as Jerusalem. These exotic characters were reputed to have special insight and hidden knowledge so when they mentioned what they had seen in the heavens they were greeted with serious concern. And they were thought to be from the land where philosophers were kings, thus they were given a royal greeting. As they arrived, looking for the culmination of their quest, they had but one further question to add to their cache of knowledge: where was this King? Herod quickly called his experts together who they readily told him the answer: the promised King of the Jews was to be born in Bethlehem, according to the prophecies. Hearing this, the Magi set out to visit. Herod presumed to treat them cleverly by reminding them: when they found the King they were to come back and tell him, so he could go and honor the new royal as well. As we read the account, even at the remove of twenty centuries, can feel the menace in Herod's voice; his duplicity seeps out from between the lines. All this being said, the Magi set out. The rest of Jerusalem went back to bed and Herod waited. The Three Kings eventually found the newborn Jesus, rendered him a king’s greeting and delivered their gifts. Because they were men of deep learning and wise understanding they paid attention to a dream warning them of Herod’s evil design. They chose not to return to their homeland through Jerusalem. Thus they avoided informing Herod and so kept from putting the child king in danger. But their own precautions set in motion the machinery of slaughter. Herod became enraged at their dereliction. As we read the account in Matthew’s gospel we become aware of a logical flaw in the story. Because they did not come back to Jerusalem, Herod could not have known exactly what happened to them. It could have been possible they did not find the King they were looking for and, upon being frustrated, left from there to go somewhere else. But the presumption of Mathew is clear: prompted by a star and informed by the scriptures, their journey would have them exhaust every possibility to find the child. Certainly, if they had not found him, they would have come back to Jerusalem to check their facts and explore an alternative. When they did not return, Herod knew: they had found what they were looking for and had refused his imprecations. In fact, Herod's reasoning was on target. And knowing these foreigners had betrayed him, Herod acted. He sent his soldiers into the region to put to the sword every child born within the three year timetable detailed by the Wise Men. The soldiers arrived, rooted out the families and killed all boys three years-old and younger. No doubt it took only a day or two. In all of its efficiency it was the work of a tyrant terrified of his throne; it is perfectly recognizable in our own world, even at the distance of two thousand years. Being Herod marked the energy of the Ancient World. As we have seen lately, the Herod option has not gone out of style. From the crafty personal rivalries of the First Century to the soulless ideological struggles of the Twenty-First, killing children in the maelstrom of politics and personalities is a human story that crosses the boundaries of time and place. This gospel account was not the first; it's recounting continues to remind us only of the latest time it has happened, not the last. The story of blood and slaughter is the human story. It is written into the rough and tumble world we know. All of human history is populated by blood, struggle and death; it is, indeed the very basis upon which the world is constructed. In the Book of Genesis Cain kills his brother Abel because of jealousy and resentment and is banished from the family. He is condemned to wander the world. And what does Cain do? According to the narration in Genesis, he becomes the founder of cities! Blood, struggle and the solidarity created by victimizing are what continually draw people together and builds societies. Most ancient creation stories, including those surrounding the Hebrews, describe their gods creating the world from the death of monsters or wild animals. Often these stories of the beginnings of the community begin with a violent killing. Creation itself is made possible by the blood of the ones slain. In short, these people told stories of the origin of humanity based on bloody violence and desperate struggle. It was the story of creation that might have been written by an urban gang or the newest Caliphate. Doing violence and honoring domination are what make people and build societies. The Greeks ended up calling it 'the logic of struggle.' It forms us into who we are. This logic is still with us. From the chants of Allahu akbar from ISIS to the Mexican altars built to Santa Muerte, from our fascination with the 270,000,000 guns in our society to the work of Capitalism and its role in ‘creative destruction,’ we are taken with the logic of struggle. We have not budged in our human awareness of the power of violence to create community and energy. One example will suffice. Thirty years ago the author, Studs Terkel published a famous and well received book about World War Two called The 'Good' War. In it he collected the stories of dozens of people who had some connection to WWII, not just soldiers and sailors but wives and children, factory workers and farmers, clergymen and college kids. All of them were the product of interviews he had done over the years. He wanted to communicate what ordinary people had experienced in this, the greatest struggle in the 20th Century. In a later interview on Larry King’s radio program he was asked about the book and his opinion regarding what had happened in the US since the war. He described his intent on writing the book and then noted a salient fact: no one seemed to notice that the word 'Good' was in quotation marks. Everyone was convinced WWII was so self-evidently good its goodness was beyond question. In fact his book was trying to communicate that even amidst the struggle to make the world better, everyday decisions became difficult and questionable things became normal. But no one noticed. Everyone presumed the violence of that war was good; no one noticed the irony he was trying to describe and highlight. Jesus, commenting on the violence of the world, cast his remarks in terms of the presence of real Evil. In one place he mentions he ‘had seen Satan fall light lightning.’ Alas, where Satan had fallen was into the world. He is here and his presence accounts for the power of violence and the prevalence of murderer. In another place Jesus calls Satan a ‘murderer from the beginning.’ Evil Personified makes his way through the world by way of the struggle and violence enveloping us all. This sounds pretty depressing and it’s normal for us to feel a little uncomfortable with such a description. After all, aren’t we more than the violence that forms around us? Haven’t we been able to make a lot of progress over the centuries? At least we don’t empower kings to slaughter entire generations of children, as Herod had the power to do. And it’s true; we have made some progress over the years. In fact, in a recent book by Stephen Pinker called, intriguingly, The Better Angels of Our Nature he lays out a startling claim: we have become more and more peaceful to one another over the years. He actually goes through the data of the various societies over the years and points out a little known fact: things have in general, at least in the West, gotten better and better for everyone. No matter how we actually feel, there is much less murder, mayhem and monstrosity among us in our contemporary societies than just about ever before. If you think about it, it is true, at least on the surface. It is present even in the everyday data of our lives. Just sit down and tune into a Western from the Golden Age of television. Notice that everyone is pulling a gun on someone else; you can see we’re certainly in a much safer territory now than then. You might also notice these movies were produced at a time in which the violence they portrayed was thought honorable and good. Remember the beginning of Gunsmoke? It may have been at the very heart of the time when television was great but every program began with the depiction of the heroic sheriff shooting a man in the street. I can’t think of any contemporary TV series whose introduction is as violent as that. Maybe we really have gotten better. It might just be that our society has become a place where innocents are protected. Pinker is resolute in assuming the root cause of the decline of violence is our abandonment of religion. He belongs to the settled opinion that piety and faith in God cause most of the violence in the world; getting rid of such irrational convictions has made us much safer. In the face of the resurgence of ISIS and the convictions of the insane Jihadi movements around the world, it’s hard not to give him a hearing. Throughout the Middle East the contemporary rise in religious convictions has now made it just about the most violent place on the planet. One of the most famous images of the middle of this last year was the video of twenty-one Coptic Christians being beheaded in Libya, the product of religious intolerance and fanatical violence. For the last few months the most famous media images have been of helpless women and children as they trudge through the cold and snow in Syria and Turkey to find their way to refugee camps in Europe. And all of this at the behest of a fanatical new commitment to religious purity, a fanaticism creating horror just about everywhere. The numbers are in: when the secular rulers ran these countries, although they bludgeoned their people into good behavior, things were much less violent than they have become. Wouldn’t just about any Iraqi (and just about any American governmental official) now prefer the regime of Sadaam Hussein than that of ISIS? And for the Iranis, the Shah rather than the Ayatollahs and for most Syrians, the Assads rather than Al Qaida? According to Pinker, peace comes with secularization. We’ll stop slaughtering innocents, he insists, when we stop genuflecting before the altars of God and start spending more time in the library, or at the mall. So maybe the reign of terror in the world is coming to an end, or at least we can see it from here. When we think about it, even Herod’s slaughter of the innocents was based on a religious understanding in the mind of the people. Herod knew the residents of his kingdom were waiting for a new chosen one who would lead them into a whole new kind of life. It was a promise made by God for those who took God very seriously. When faced with what he knew to be intransigent fanaticism, Herod made his choice about how to stay in power; he sought to head off the religious threat to his kingdom. With the decline of religious promises, perhaps there will be fewer innocents to slaughter. Or at least the leaders in power will have less reason to fear religious threats. At least we could hope so; or at least Herod might think so. Alas, Pinker has stacked the deck. Unfortunately for him, another notable story to come out of this last year was the one almost buried by the mass media. It was the story of the 12 undercover videos (more than 15 hours of recordings) of Planned Parenthood officials and their complicated efforts to market the body parts of children, the byproducts of their procedures. In the calculus of violence Pinker does not include this particular cost of working and living in our society in our day and time, a price that includes taking the lives of one million of the children conceived every year. For him this is simply the way the world works; in his view it’s not violent at all and so does not matter in the measure of things. He’s happy to report a declining murder rate as well as fewer wars and a lot less sexual assault as the first fruits of a secular society but he does not even notice the sale of freshly harvested (in the words of those who sell them) livers and brains. We have not made quite as much progress as is claimed. Other acts of violence in the world also go unmentioned, mostly because they are not seen. Environmental degradation that spends irreplaceable resources and damages the world for everyone; those costs are not calculated. The gigantic prison population that marks life in the United States, which includes the largest population of young men and women imprisoned of any jurisdiction anywhere on the planet, is a dark shading on the portrait of our society. And of course there are the untold trillions spent worldwide to arm ourselves for protection and deterrence. Each dollar spent for a bullet is also one not spent on a water well or a chalk board. And the list goes on. Pinker does not have it right, not even by a little bit. The world he is so proud of, the one he celebrates for throwing off the straightjackets of religion, is perfectly happy assaulting the innocent and offending the helpless. You don’t have to be a believer to believe in he who was a murderer from the beginning. We’re not going to find a way out of the morass of murdering the innocent by turning away from the complications of religion. As Catholics we know, human beings are religious; it is wired into our DNA and we’re going to find it one place or another. Our current devotion to human sexuality is perfectly religious, for example. It transcends any individual person and experience; it depends upon a credo that can be believed only by faith; its ultimate appeal is to loosen the bonds that constrain us and it is defended by those willing to kill to keep it in place. If we begin counting the bodies, including the ones whose parts are being marketed, we see our new social order is carpeted with corpses. Our new secular order is built on the logic of struggle and invested with the power of violence. Herod would be at home here. There is an alternative. We are not hopelessly trapped inside of Herod’s mind nor are we condemned to mothers’ tears. In fact, we have a word for this alternate state of things: it is called “The Church.” As Gil Bailie once said: “The Church is the anthropological experiment being carried out in society when we begin to live sacramentally rather than sacrificially.” Our great hope is to begin living the message of Christ, a message of forgiveness, forbearance and freedom. We defeat Herod first by standing on the side of the innocent and, second, suffering with those who suffer. When we do these things we are creating an entirely new logic of living. We are beginning to see it in faint form already. Right now in Europe we see some dim hints of what it looks like. As the refugees from Syria and Iraq make their way across the borders into the heart of Europe they are, for the most part, being welcomed and provided for. It is a difficult journey and they would rather not make it but there is hope waiting for them as they arrive, mostly. And when the rest of the world hears there may be rising tensions accompanying the arrival of these people there is a general sense of disappointment. The common feeling is that refugees as pathetic as these should be given some help and find some welcome; it is the genius of the Western World to do such a thing. As René Girard wrote: “The West is Christian and the world is Western.” The Christian response is to welcome; if we don’t, the world is disappointed. This is the logic of living rather than dying, a world bathed in light, not in blood. Of course, Europe knows about refugees and people in motion. Seventy years ago tens of millions of people (not merely tens of thousands-as today) were in motion across the European landscape seeking shelter from the ravages of war and starvation. European nations should know, as much as any jurisdiction can, the reality of mothers who huddle with their children in miserable shelter in order to wait on the mercy others provide. They know suffering. The hope is that all of us connect what we know to what we see. This is the work of the Church in the world. Perhaps it is happening. In the year to come we will all be challenged to extend mercy to one another. We will be invited to connect our lives to the lives of those who suffer the pains of anxiety and fear. The temptation will always be to lapse back into the logic that has built the crooked structures of our fallen world. But the pathway forward is to overcome this temptation by our connection to the holiness of innocents and the sanctity of their needs. It won’t be easy. We will have to struggle to see ourselves in them. The greatest challenge will be to remain focused when a thousand other voices will be shouting at us to trust in violence and exclusion. But the great invitation lies in front of us. The Lord of all was given the gift of life in the midst of the death of innocents. When we remember the suffering of the innocent we invest ourselves in following the Lord into life. Fr. Don Wolf