- Senior Sequence

advertisement

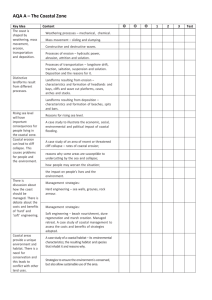

The Sustainable Coastline Management The Recommendation of Policy Making for the Costal Management A research proposal submitted to the Urban Studies and Planning Program Senior Sequence Class 2011-2012 October 18, 2011 Kosuke Morishima University of California at San Diego Urban Studies and Planning Program USP 186 Email: kosuke06523@yahoo.co.jp Abstract For all future projects, people are required to think about one question: what should be the relationship between nature and humans? This question is necessary because global warming is rapidly increasing and the threat to the environmental issues is close to our daily-life. In recent years, especially one of the most certain outcomes of global warming is an increase of global sea level. Researchers found that this issue causes economic, environmental, and political problems. Consequently, if the sea level rises, the local government along the coastal line is threated with losing the strong tourism and tax revenue. In addition, private property owners face the threat to lose their land and to risk a serious natural disaster. Therefore, this study examines how the sustainable plans of the coastal areas’ work adapt to the threatened coastline, in order to manage a better coastal line. This study will contribute ideas how the government should establish accurate policies and plan valuable projects to develop the sustainable coastline. This study will be based on assisting the potential contribution of indicators to assess the performance of the governance process involved in integrated coastal management. The research design is based on the evaluation phase and the need to complement process-oriented indicators with outcome-oriented indicators to improve adaptive management and accountability. The study will contribute to create an indicator of evaluating policies to develop the sustainable coastal area, as well as a costal management. Therefore, the result will be shared with the government, developers, and planners who plan policies and projects in the coastline, in future. In addition, the example of integrated management of marine protected areas is used to propose a menu of indicators of global applicability and create sustainable coastlines. 1. Introduction Costal erosion is a global issue; at least seventy percent of sandy beaches around the world are recessional (Bird, 1985: 219). In the United States, approximately eighty six percent of U.S. East coast barrier beaches (excluding evolving spit areas) have experienced erosion during Morishima 1 the past hundred years (Galgano et al., 2004: 283-284). Also, this phenomenon was caused in California (Moore et al., 1999: 124) and in the Gulf of Mexico (Morton and McKenna, 1999: 110). These past experiences, regarding the coastal erosion are mostly a natural phenomenon. The important factor when understanding the issue of the costal erosion and the rising of sea level is that the coastal erosion has occurred since long ago as one of the natural phenomena. The problem that has to be focused is the ‘rapidness’ of improving and globally expanding the phenomenon as a serious environmental issue. Furthermore, the difference of the past land condition is that the most coastal areas exist as private properties. The result of this environmental issue will heavily impact low-lying areas; at least one hundred million persons live within one meter of mean sea level and are at increased risk in the coming decades (Zhang, 2004: 41). The private property owners will be threatened by the economic damages. Moreover, as the beach is lost, fixed structures nearby are increasingly exposed to the direct impact of storm waves, and will ultimately be damaged or destroyed, unless expensive protective measures are taken. It has long been speculated that the underlying rate of long-term sandy beach erosion is two orders of magnitude greater that the rate, if the sea level rises, so that any significant increase of sea level has dire consequences for coastal inhabitants (Zhang, 2004: 42). Therefore, the local and states governments will lose huge economical assets and expend much budget to the land and the social condition. Thus, to reduce the risks of the tragic situation, the government needs to set indicators to consider and institute the effective policies to create the sustainable costal communities. The consideration should be based on the three points of views stated above, environmental conservation, politics, and economics based on a clear understanding of the phenomenon of coastal erosion. 2. Understanding the Costal Erosion: Conceptual Frame work Morishima 2 and Literature Review Not only to establish and develop the valuable policies but also to indicate the direction of projects and policies, it is very important to indicate the best sustainable solutions with a clear and well-understood assessment. To measure governance performance in integrated coastal management, the understanding what the costal erosion is and how it occurs is absolutely necessary. The global warming causes most of the environmental problems, and it leads to a variety of the second phenomenon, as well as the sea level rising and climate changing. Then, the costal erosion, flooding, and other natural disasters are caused. In addition, by combining these phenomena with the environmental problems and density-populated urban areas, the natural disaster expands and accelerates itself even more. Coastal erosion is a natural process influenced by humans; it consists of erosion, transport and deposition components that collectively modify coastal landforms (Wilson, 2010: 5). Thus, coastlines have been kept changing for a long time, and all these processes differ both temporally and spatially, while cliffs tend to retreat (Auckland Regional Council, 2006). The primary factor of the coastal erosion is the climate change (Ramsey and Bell, 2009: 138). In addition, creating the sandy beaches takes several thousands of years before the rocky material creates any real abundance of sand to fill a beach. Then, when considering impacts of the sea level rise, it is very important to distinguish inundation (to cover with water, especially floodwaters) from erosion. Concerning the former, as the sea level rises, the high water line will migrate landward in proportion to the slope of the coastal area. In some areas, the slope is very gradual, and the impact from the sea level rise can be severe (Zhang, 2004: 42). A phenomenon such as the erosion of sandy beaches is a physical process entirely different from inundation. It includes a redistribution of sand from the beach face to offshore, and it is most commonly carried out Morishima 3 during coastal storms. These storms are caused by a temporary increase of local sea level (the storm-generated surge above the normal astronomical tide) so that energetic storm waves are able to attack higher elevations of the beach and dunes (Zhang, 2004: 42). Sediments in these places are extracted and put into suspension by the waves and carried offshore. Much of the sand returns to the beach after the storm by long-period swell waves, during normal water level. This phenomenon suggests that water level plays an important role in beach erosion; For example, a quantitative demonstration of the relationship of storm erosion magnitude on the U.S. East coast from northern Easters and their accompanying storm tide amplitude and duration has been give (Zhang, 2001: 309). Next, to understanding the coastal erosion and denying that occurs the projects with a temporary solution, defining the factor, included natural and artificial phenomenon, of the coastal erosion also contributes to create the policies and plans of public projects. By clearing the differences of the factors between natural phenomenon and human intervention, the indicators can assess plans with the idea of what policies the government should not establish. In general, there are main, seven natural factors: 1) the sand sources and sinks, 2) changes in relative sea level, 3) geological characteristics of the shore, sand size, density and shape, 4) sand-sharing system of beaches, 5) dunes and offshore bars, 6) effects of waves, currents, tides and wind, and 7) bathymetry of the offshore sea bottom (Turekian et al., 1996). The research states that there are six other beach erosion factors: 1) effects of human impact, such as construction of artificial structures, mining of beach sand, offshore dredging, or building of dams or rivers, 2) loss of sediment offshore, onshore, alongshore and by attrition, 3) reduction in sediment supply due to deceleration cliff erosion, 4) reduction in sediment supply from the sea floor, 5) increased storminess in coastal areas or changes in angle of wave approach, 6) increase in beach saturation Morishima 4 due to a higher water table or increased precipitation (Turekian et al., 1996). Also, there are other six factors which change through people’s intervention. Three of the main factors should especially be focused upon, as improvements through people possible. The first factor is the construction of groins and jetties. They are built on the area of shoreline and set perpendicular to the coastal line. The purpose of constructing jetties is to protect the coastal area from the hurricanes, as well as to moderate the radical ocean currents at the area of a harbor. However, jetties break the continuity of the sand and silts flow. Silt and sand comes from the river, ‘other beach areas’, ‘bluffs’, and ‘rocky shores’, and then they flow and move with the sea current. In the case, where the ocean current flows south from north, silt and sand also flow on the same direction. Also, two jetties are set from the coastal line to the ocean in front of a harbor or the mouth of a river. In that case, the jetties stop or break the continuity of the sand flow. Then, silts and sands accumulate at the north side of the jetties along the beach, and erosion happens at the beach of the south side of the jetties. The second factor is the dams. The silt and sand that come and accumulate on the beach flow from the river. However, dams stop that flow on a river, on its route to the ocean, and silt and sands accumulate at the bottom around the dams. The sediments that are moved by the water are trapped behind the dam, even though the water is allowed to flow through, in a controlled fashion. Therefore, this construction becomes the trap of sediments and deprives the beach of material that could be used to build it up through wave action. The main reason why the government would like to save the coastal area by the environmental issue of the coastal erosion is that tourism is one of the most important economic sectors, worldwide, and few environments are more important for tourism and recreation than coastal zones. For many centuries, the cost has been a major resource for recreation, and the intensity and diversity of activities seem to be continuously growing (Hall, 2011; Miller, 1993; Morishima 5 Orams, 1999; Orams, 2007). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), jointly with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) convened, in 2007, the Second International Conference on Climate Change and Tourism, in Davos (Switzerland). More than four hundred and fifty participants, from over eighty countries, participated. The conference declaration states that climate is a key resource for tourism and the sector is highly sensitive to the impacts of climate change and global warming, many elements of which are already being felt. It is estimated that contributes global warming some five percent of global CO2 emissions (UNWTO, 2007). Also, the great diversity of activities and the expansion the sector is now experiencing are related to socioeconomic factors and costal population growth. Most importantly, the development of, as well as easier and cheaper access to advanced technology, has dispersed coastal and marine recreation to virtually every corner of the world, from the poles to the tropics (Hall, 2001; Orams, 1999). At the global level, there is no data about participation and revenues for most of coastal and marine activities; however, some studies about specific sectors and regions can give an idea about the relevance of the sector. Researchers state that eighty million Americans (forty three percent of the population) participated in at least one marine outdoor activity in 1999-2000 (Leeworthy and Wiley), 2001. One sector that has experienced rapid development in the last years is the cruise industry; the segment of two to five-day cruises in the North American market has even grown by one thousand and eleven percent between 1980 and 2007 (CLIA, 2008). Recreation demand models can be used to assess visitors’ value of access to beach sites; for example, the value of a beach day in North Carolina is $11 to $80 per person (Bin et al., 2005), while the value of a California beach day is $21 to $23 (Lew and Larson, 2008). Increases in beach area provide additional space for coastal recreation and leisure Morishima 6 activities, and may enhance value by allowing for increased utilization of beach resources, or by decreasing congestion for existing users. The researchers find evidence that the value of a beach day increases with modest improvements in beach width (Landry, Keeler, and Kriesel, 2003), while it has a positive but insignificant effect of increased beach width on visitor economic values (Whitehead et al., 2008). Thus, the environmental problems largely relate to the economic impact; the reason why the government and private property owners along the coastal lines need to consider the issue of losing coastlines implies that tourism on coastal areas affects the majority of the economical damages. Another point of view to consider regarding costal erosion is the fact that the coast provides a range of resources that benefits society as a whole. While a small number of residents enjoy the coastal benefits year-round, thousands of citizens enjoy them periodically. Both sets of coastal users are affected by management decisions related to coastal erosion. Decision-making regarding coastal erosion is often based on cost-benefit analysis, but the perspective of equity or social justice raises additional considerations regarding public intervention, particularly when private property is threatened (Cooper, 2008). The management approaches of the coastal erosion have benefits and costs that are not shared equally among those affected by erosion. Decision-making in coastal erosion management is dominated by cost-benefit analysis. For small communities, it is more difficult to make a positive cost-benefit ratio for costal defense; for instance, in southeast England, a recent potential decision to stop defending a section of the coast met with opposition from the affected community. The residents argue on the basis of ‘social justice’ for public intervention, since a cost-benefit analysis was unlikely to produce a decision favorable to those residents. This has prompted some recent consideration of how this concept might be applied more generally in coastal erosion management (Cooper and McKenna, 2007). Morishima 7 An all-party of the UK parliamentary group on coastal issues recently considered the potential role of social justice in coastal defense planning. To discuss the potential contribution of indicators to evaluate the performance of the governance process, it is important to understand what the governance is and how it occurs. Governance is the process through which diverse elements in a society wield power and authority and, thereby, influence and enact policies and decision concerning public life and economic and social development. Governance is carried out by the state, as well as the private sector and civil society. With relation to integrated coastal management (ICM), governance refers to the structures and processes used to govern behavior, both public and private, in the coastal area and the resources and activities it contains. ICM refers to the process through which the use of specific resources or portions of the coastal area are managed to achieve desired objectives. While the coastal area governance system can apply to the conduct of a single activity, for instance, control of coastal erosion, what distinguishes ‘‘integrated coastal management’’ from ‘‘coastal management’’ or ‘‘coastal resource management’’ is the ability to create a governance system capable to manage multiple uses in an integrated way through the cooperation and coordination of government agencies at different level of authority and of different economic sectors (Ehler, 2003). 3. Research Design/ Methods The method of this research paper will be to evaluate policies by measuring the performance of integrated coastal management (ICM), the role of indicators, to create sustainable coastline, and to make the recommendation for the policies of marine protected areas (MPAs), provide an example of integrated approach to the management of coastal and marine areas. Thus, this research paper will be based on the indicators’ attributions (will be given below). Given the Morishima 8 complex nature of the governance processes involved, ICM is confronted with the challenge to establish measurement systems able to adequately track the progress of efforts. Greater emphasis on performance can help make ICM more oriented toward outcome-based results rather than on input-based accounting. As a successful method, in both environmental and socioeconomic terms, can be judged in terms of improved water quality, increased public access to beaches, decreased habitat loss, reduced coastal hazards, or increased employment in coastal-related activities. With using the ICM policy cycle (See Figure. 1), evaluation will answer two major needs, accountability and adaptive management. In practice, assessment’s results are mostly used in more than one way (Pomeroy and Watson, 2002). Information used by managers to develop the performance of their management skills and strategies, adaptive management, will also help for reporting, accountability, or lessons learned by others to improve planning in future. Planning Evaluating Implementation Monitoring Outcomes Figure. 1The ICM policy cycle. To evaluate the performance, ICM initiatives should be categorized by clear goals accompanied by quantifiable objectives, and the information, based on indicator for ICM, should Morishima 9 include some basic conditions: being simple, quantifiable and communicable. To this end, indicators for ICM should have a number of attributes that make them suitable, such as: 1) Being relevant to management objectives and scientifically valid, 2) Being developed with all those involved in management, 3) Being credible, easy to understand, and unambiguous, 4) Being credible, easy to understand, and unambiguous, 5) Focusing on the use of information, not on gaining it, 6) Having a clear link to the environmental outcome being monitored, 7) Being continuously reviewed and refined when necessary, as part of adaptive management, 8) Providing early warning of emerging issues or problems, 9) Being capable of being monitored easily to show trends over time, 10) Using accepted and clearly documented methods and units, 11) Being as simple and cheap as possible, and 12) Being adaptable for use at a range of scales, wherever possible (Ehler, 2003). To advance the development of indicators, partnership between governments, communities, the private sectors, NGOs, and research institutions should be organized to set up and run the process. Important contributions can also come from continuing research and development to provide the most appropriate indicators and to understand cause and effect relationships, as well as to raise awareness of the links to wider social and economic considerations (Ehler, 2003). Nevertheless, the development of indicators have to care some elements; for example, collecting data outside the relevant management context, not enough feedback from stakeholders, limited link between performance measures and resource allocation, and excess of bureaucratic inertia (Salm and Siirila, 2002). When considering future directions for governance indicators, as the understanding of coastal system developments, it will be possible to select better, more cost-effective indicators, improved instrumentation will allow more sensitive detection and monitoring, real-time measures and more powerful modeling will Morishima 10 capture and analyze data more quickly, visualization techniques will allow more ready use by managers, and indicator use will feed to better reporting and communication (Ehler, 2003). Therefore, the indicators can help to create the recommendation of policies for sustainable coastline with the development that contributes to saving the natural environment, the local economy such as a strong tourism, and to maintain the social basis for the citizens and private property owners in the coastal areas. The result of evaluation by indicator must be the basis and lead to create the recommendation, which contributes each government to consider the necessary policies for the communities. 4. Conclusion The costal erosion as well as the environmental issues by human intervention will not stop and will rather accelerate to negatively affect various field of human life: economically, socially, and environmentally. First, understanding the erosion itself, and separating it in categories, as natural phenomenon or human intervention, is important. For example, the dams really contribute to improve coastal erosion. Then, developers and planners who create projects at the coastline should be aware of this knowledge and studies, and then consider what project to develop regarding the sustainability of costal areas. The main reason why this research is necessary is that tourism on the coastal areas strongly supports tax revenues of local governments and support the local business of the citizens. The communities along coastlines in the globe will benefit by managing the local economy. In addition, the maintenance of coastal line is important economically and socially. Therefore, the loss of the coastal areas will bring serious damages in the global scenario. To deny the tragic situation, this research will evaluate and measure the performance of the governance process involved in integrated coastal management, as the indicator. The result of the evaluation as the indicators will be the basis of Morishima 11 the recommendation for establishing new policies and show the government what concepts will be embraced by local communities, and how will policies work to support the local economy, social fairness of the property, and environmental conservation; for example, the evaluation, as the indicators, will includes the judgments in terms of improved water quality, increased public access to beaches, decreased habitat loss, reduced coastal hazards, or increased employment in coastal-related activities. References Auckland Regional Council (ARC). (2006). Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion. Volume 1. TR 2009/009. Barry, B., 1995. A Treatise on Social Justice Volume II. Justice as Impartiality. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Bird, E.C.F.: 1985, Coastline Changes, Wiley & Sons, New York, 219 pp. Bin, O. C.E. Landry, C. Ellis, and H. Vogelsong, 2005. Some Consumer Surplus Estimates for North Carolina Beaches, Marine Resource Economics 20(2): 145-61. Beckerman, W., 1999. Sustainable development and our obligations to future generations. Dobson, A. (Ed.), Fairness and Futurity: Essays on Sustainability and Social Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 71–93. Elbel, F., 2002. Intergenerational justice. The Social Contract, 13, 12-18. CLIA, 2008. CLIA cruise market overview - Statistical cruise industry data through 2007. Cruises Lines International Association. Available at http://www.cruising.org/Press/overview2008 Cooper, J.A.G. and McKenna, J. 2007. Social Justice and coastal defense: the long and short term perspectives. Geoforum (in press). Cooper, J.A.G. and McKenna, J. 2008. Concepts of Fairness in Coastal Erosion Morishima 12 Management. Centre for Coastal and Marine Research, School of Environmental Sciences, University of Ulster, Coleraine, BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland Ehler, Charles N. 2003. Indicators to measure governance performance in integrated coastal management. Elsevier Press. Ocean and Costal Management 46 (2003) 335-345. <http://www.costabalearsostenible.com/PDFs/AMYKey%20References_Indicators/Ehler %202003.pdf> Galgano, F. A., Leatherman, S. P., and Douglas, B. C.: 2004, ‘Inlets Dominate U.S. East Coast Shoreline Change’, J. Coastal Research, in press. Hall, C.M., 2001. Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: the end of the last frontier? Ocean & Coastal Management, 44, 601-618. Hardin, R., 1987. Social justice in the large and small. Social Justice Research, 1, 83 105. Haynes, K.E., Lall, S.V. and Trice, M.P. 2001. Spatial issues in environmental equity. International Journal of Environmental Technology and Management,1, 17-31. Landry, C.E., A.G. Keeler and W. Kriesel, 2003. An Economic Evaluation of Beach Erosion Management Alternatives, Marine Resource Economics 18(2): 105-127. Leeworthy, V.R. and Wiley, P.C., 2001. Current participation patterns in marine recreation. National survey on recreation and the environment 2000. Silver Spring (Maryland), U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (U.S. Department of Commerce). Lew, D.K. and D.M. Larson, 2008. Valuing a Beach Day with a Repeated Nested Logit Model of Participation, Site Choice, and Stochastic Time Value, Marine Resource Economics 23(3): 233-252. Ramsey, D. and Bell, R. (2009). Preparing for coastal change - A guide for local government in New Zealand. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington, New Zealand. Moore, L. J., Benumof, B. T., and Griggs, G. B.: 1999, ‘Coastal Erosion Hazards in Santa Cruz and San Diego Counties, California’, J. Coastal Research No. 28 (Special Issue), 121–139. North Norfolk District Council, 2005. Shoreline Management Plan Position Statement. <http://www.marinet.org.uk/coastaldefences/smp.html#nnd> Morishima 13 Orams, M.B., 1999. Marine tourism: development, impacts and management, London: Routledge. Pomeroy R, Parks J, Watson L. ‘‘How is Your MPA Doing?’’ Draft. Guidebook for Evaluating Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Washington, DC: WCPA-Marine & WWF, 2002. Ramsey, D. and Bell, R. (2009). Preparing for coastal change- A guide for local government in New Zealand. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington, New Zealand. Ramsey, D. and Bell, R. (2009). Preparing for coastal change- A guide for local government in New Zealand. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington, New Zealand. Salm R, Clark J, Siirila E. Marine and Coastal Protected Areas: A Guide for Planners and Managers. Washington, DC: IUCN, 2002. Taylor, J.A., Murdock, A.P., Pontee, N.I., 2004. A macroscale analysis of coastal steepening around the coast of England and Wales. The Geographical Journal, 170 pp. 179-188. UNESCO, 2007. Case studies on climate change and world heritage. Paris, United Nation Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Wilson, Amanda. 2010. ‘Coastal planning in North Shore City, New Zealand: Developing responsible coastal erosion policy’. AARES Conference. Whitehead, J.C., C.F. Dumas, J. Herstine, J. Hill, and B. Buerger, 2008. Valuing beach access and width with revealed and stated preference data, Marine Resource Economics 23(2): 119-135. Zhang, K., Douglas, B.C., and Leatherman, S.P.: 2001, ‘Beach Erosion Potential for Severe Nor’easters’, J. Coastal Research 17, 309-321. Zhang, K., Douglas, B.C., and Leatherman, S.P. 2004, ‘Global Warming and Costal Erosion’, Laboratory for coastal Research and International Hurricane Research Center. Morishima 14