April 23

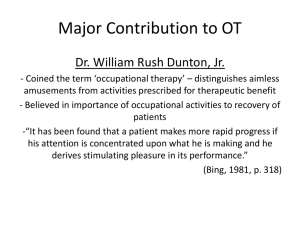

advertisement

Creativity and Capital: Herbert Hall, George Barton and the Making of Occupational Therapy, 1905-1923 ~for pre-circulation~ Social Science Research Seminar - Wakeforest University, April 24, 2015 *draft document – please do not cite without permission* Sasha Mullally, Associate Professor, History University of New Brunswick In upstate New York, in the picturesque spa town of Clifton Springs, architect and industrial designer George Barton worked with patients to produce models of farm houses, barns, and chicken coops, items that they crafted from modified carpentry tools adapted to their debility or disability. In the workshop and on the premises of his sanatorium, Consolation House, Barton and his clients created a model vision of an artisan community and rural American farm. Meanwhile, in the colonial seaport of Marblehead Massachusetts, physician Herbert Hall ran medical workshops where patients embraced the craftsman ethos to speed their recovery from nervous diseases and physical debilities. In a variety of weaving, pottery and metalworking workshops at his sanitorium, Devereaux Mansion, they fashioned objects for sale evocative of the arts and crafts revival movement, especially woven coverlets and cement-ware pottery. These two environments, colonial throwbacks situated within the larger late-industrial American landscape, were meant to offer patients restful occupational while they convalesced from a variety of psychological and physical ailments. At Consolation House and Devereux Mansion, patients learned to use and develop what ability they had to execute skilled carpentry and create quality crafts, with the idea that occupation itself constituted a form of therapy. In the early twentieth century, North American professionals and health care practitioners across several domains -- psychiatry, education, industrial design and nursing, among others -- joined forces to form a new clinical sphere of practice they called occupational therapy (OT). These OT advocates supported the widespread and systematic adoption of creative work to treat everything from mental illness, to rehabilitate disabled workers, from giving wounded soldiers a new lease on life, to assist patients cope with a variety of chronic illnesses. They gathered together for a meeting of the “First Consolation House Conference” in the late winter of 1917. The stated purpose of the gathering was to share ideas about work cure techniques, but attention quickly turned to the larger challenge of advancing a new profession within medicine. On March 16, 1917, they created the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy (NSPOT) and George Barton would serve as its inaugural president. 1 The invited guests were Dr. William R. Dunton, psychiatrist at Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital, Thomas B. Kidner, Vocational Secretary of the Canadian Military Hospitals Commission, Eleanor Clarke Slagle of Hull House in Chicago, and Susan C. 1 Herbert Hall’s absence, and his ambivalent status as a founder, is noteworthy, for, as founder of an early experimental workshop for OT, in many ways he was a rival to Barton’s authority within this group.2 Hall’s ideas about the value of work to improve the therapeutic outcomes for neurasthenics were very influential by the turn of the century. The commercial success of Marblehead Pottery, produced from his handicraft workshop at Devereux Mansion in association with highly skilled craftspeople, had made him well-known as successful sanatorium operator. Additionally, his notion of a “work cure” had earned him grants from Harvard Medical School, and a following among many interested medical practitioners. Hall was one of many clinicians active in the first decade of the 20th century who married philosophy with biology in their conceptualizations of therapy.3 With the understanding that bedside occupation could be much more than a mere distraction for the unwell, Hall advanced the notion that mental and spiritual rejuvenation of his patients, who were mostly women suffering from neurasthenia, could be treated with the craftsman ethos. Patients were relieved of their psychological distress through the production of quality craft items, buoyed and validated by their commercial value. Barton was also a firm believer in the value of work in convalescence, althugh this stemmed from personal experience as a patient rather than a practitioner. An Johnson, who was Director of Occupations at Blackwell’s Island, but who would soon to be recruited to Columbia University where she would become an instructor in courses for re-educating WWI soldiers. Other members associated with this group, though they were not in actual attendance, included Susan E. Tracey, Director of the Experiment Station at Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, well-known psychiatrist Adolph Meyer, and the aforementioned Herbert J. Hall. A complete rendition of these events is available in many published sources, but see Irene Newton Barton, “Consolation House,” unpublished article, c. 1919. Foster Cottage Archives, Clifton Springs, New York. 2 This is due, in large part, to the publishing from Susan Hall Anthony, his great niece. See Susan Hall Anthony, ““Dr. Herbert J. Hall: Originator of Honest Work for Occupational Therapy, Part 1,” Occupational Therapy in Health Care 19, 3(2005): 319 and “Dr. Herbert J. Hall: Originator of Honest Work for Occupational Therapy, part 2,” Occupational Therapy in Health Care 19, 3(2005): 21-32. Hereafter referredto as “Herbert J. Hall, Part 1” and “Herbert J. Hall, Part 2,” respectively. One clinician and historian who advances an argument in favour of embracing Hall as a founder is Kathlyn L. Reed, “Hall and the Work Cure,” Occupational Therapy in Health Care 19,3 (2005): 33–50. 3 Well-known Boston physician, Richard C. Cabot, for instance, is often quoted as observing how the right kind of creative work would be “energy transforming” for the tuberculosis patient, writing in 1909 how “…it is a dangerous experiment to take a man away from his work and put him on his back in a steamer chair for months at a time.” Richard C. Cabot, Social Service and the Art of Healing (New York: Moffatt, Yard and Company, 1909), p. 81. architect with training in industrial design, Barton was also influenced by Arts and Crafts revivalism, but his focus was more in line with the precepts and goals of vocational education. At Consolation House, he attempted to harmonize the invalid workers’ craft knowledge and skill with an adapted tools and infrastructure to accommodate the debility in question, all with a view of returning the patient to paid work. For Barton, the material cultures of occupation as therapy lay not in the material product of the patient’s labours in the workshop, but in the “reeducation” of the patient so the work itself might cure and enable him to reenter a vocational sphere. For Hall, health was manifest in the aesthetic and commercial value of the object; for Barton, health was restored by cultivating the adapted ability of the patient. These differences aside, both of these influential men placed significant emphasis on health as a state cultivated in particular material environments (therapeutic workshops), in pursuit of particular material objectives (restoration of occupational capacity). Moreover, they were the only North American practitioners of early, formalized OT to pursue experimental treatments in privately owned and operated workshops. As Kathlyn Reed has pointed out, Devereux Mansion and Consolation House may be considered the “first sheltered workshops“ for ambulatory convalescents participating in occupational therapy programs.4 Despite their importance to occupational therapy history, the environments, products and values of such early influential, experimental sites have not been subjected to historical scrutiny and Barton and Hall’s contributions have never been considered in comparison to each other. Yet, both practitioner’s sites emerged at a moment when eager experimentation in occupational therapy was generating both wild romantic claims and unbridled enthusiasm for the possibilities of the new field. This paper will show how practitioners like Hall and Barton played key roles in the making of Occupational Therapy. Both men believed they could rehabilitate patients made ill or injured by the violences of industrial capitalism by sheltering them and guiding them therapeutically through the processes of productive pre-industrial handicraft and agriculturally-focused design work. Both practitioners failed to consistently render the objects and skills “saleable” in the open marketplace for artisanmanufactured goods in an era which saw the a decline in the viability of preindustrial rural life. Nonetheless, their attempts to pursue such therapeutics in the first two decades of the twentieth century is noteworthy because both did succeed in rendering objects and skills valuable in the medical market for new and innovative rehabilitation therapies. Tracing key transitions within Hall and Barton’s occupational therapy workshops (in terms of their set up and their material outputs) reveals a fundamental incongruity of the therapeutic and economic goals pursued in early sheltered workshops for OT, highlighting this unexpected success.. Literature Review Kathlyn L. Reed, and Sharon N. Sanderson, Concepts of occupational therapy, 4th edition (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999), p. 442. 4 The history of occupational therapy is a field with a rich tradition of clinicianhistorian engagement; such writers dominate the literature. For clinician-scholars, history seems to offer a grounding central narrative for a profession continually navigating the terrain between the arts and sciences.5 As such, the historiography tends to address questions about the field’s philosophical heritage and the early challenges of professionalization. Especially since the 1980s, this “intellectual heritage” of occupational therapy has offered many clinicians a blueprint to help manage and shape a profession that was rapidly expanding, but which continued to cast about for a core clinical curriculum.6 Since that time, many practitionerhistorians have paid special attention to the writings of the “founders” of the field, as if the key to the profession’s future could be found at its moment of its formal organizational inception—a moment shaped by practitioners like Barton and Hall.. Such histories can be found in all professional writings about the field, including research notes in professional journals7 chapters in occupational therapy textbooks,8 as well as book-length treatments written by clinician historians or Writing in the mid-1980s, Karen Serrett observed that charting a history of occupational therapy would help practitioners navigate and assimilate the multiple foundations of their practice in the psychological, social and biological sciences together in service to patients. Karen Diasio Serret, “Another Look at Occupational Therapy’s History: Paradigm or Pair-of-Hands?,” Philosophical and Historical Roots of Occupational Therapy, Diane Gibson and Karen D. Serrett, eds. (London: Hayworth Press, 1985), pp. 3-24. 6 Serret, who is often cited and whose ideas are often echoed in the literature emergent form other clinician-historians, believed that a discussion of historical underpinnings can reconcile “great internal debates” about the role and clinical orientation of OT in a new “systems” age” of service workers. Serrett, 6. 7 For Canada, see Amy Sedgwick, Lynn Cockburn and Barry Trentham, “Exploring the mental health roots of occupational therapy: a historical review of primary texts, 1925-1950,” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 74,5 (December 2007): 407417. The clinician histories also include historical treatments in professional OT Journals, such as Suzanne M. Peloquin, “Occupational Therapy Service: Individual and Collective Understandings of the Founders, Part 1,” American Journal of Occupational Therapy 45, 4(April 1991): 352-260 and Peloquin, “Occupational Therapy Service: Individual and Collective Understandings of the Founders, Part 2“ The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 45, 8(August 1991): 733-744. 8 Occupational Therapy textbooks tend to include a historical timeline to situate current practice in a longer context. See D. M. Gordon, “The history of occupational therapy,” Willard & Spackman’s Occupational Therapy, 11th edition, E. B. Crepeau, E. S. Cohn, & B. A. Boyt Schell, eds. (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009), pp. 202-215 and well as the historical themes covered by Reed and Sanderson, pp. 14-30. The history of occupational therapy in mental health in the US, Scotland and the UK is summarized by Catherine F. Paterson, “A Short History of Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry,” Occupational Therapy and Mental Health, Jennifer Creek and Lesley Lougher, eds. (London: Churchill Livingstone, 2002), pp. 3-16. 5 sponsored by professional organizations, all written for the purposes of professionbuilding.9 While the earlier works in this genre have tended to overlook or downplayed the role of handicrafts,10 more recent work has used the early craft workshops as a starting point for understanding the identity politics of early OT, and for investigating the specific definitions of holistic practice adopted by early practitioners. These writings reveal a growing appreciation of how the objects of occupational therapy reveal elements of early practitioner’s plural professional identities (as both clinician and craftperson), and occupational therapy principles are formed from and linked to ideas and anxieties about work and working life.11 Many such researchers point to the history of psychiatry, and see asylum “moral therapy” as a starting point for historical analysis of OT’s origins.12 Occupational Therapy arose from a desire to schematize therapeutic craft work, and render a series of craft-related tasks on a scale of wellness, depending on how advanced the task was and how much creative energy went into performing the discrete actions. For many clinicians doing history, the quality of the work, and the creative activity of craft-making, differentiated the new orientation of occupational therapy from previous moral therapy work cures.13 Herbert Hall’s idea of a graded craft work, still used today, fits within this paradigm, while his work and idea about creativity have fallen by the wayside. Still, there is widespread historiographical consensus that a significant turning point for OT came with the return of wounded WWI soldiers and sailors as the need for both physical and psychological rehabilitation lent considerable impetus to the field. See Virginia A. M. Quiroga, Occupational therapy: The first 30 years 1900-1930 (Maryland: The American Occupational Therapy Association, 1995). For Canada, a recent and important book-length study is Judith Friedland, Restoring the Spirit: The beginnings of Occupational Therapy in Canada, 1890-1930 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011). 10 Friedland, for instance, has noted how North American clinician historians “prefer to dismiss crafts as an unfortunate part of our [professional] past…as if we are ashamed of these occupations.” Friedland, “Why Crafts?: Influences on the development of occupational therapy in Canada from 1890-1930,” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 70, 4 (October 2004): 204. 11 Jennifer Laws traces what she calls a “therapeutic work ethic” from the first decade of the 19th century through to the 1970s arguing the history of therapeutic work is a part of the “broader human struggle with work” itself. Jennifer Laws, “Crackpots and Basket Cases: A History of Therapeutic Work and Occupation,” History of Human Sciences 24, 2(2011): 65. 12 As Laws points out, these were bolstered by the fact that the gardening, sewing, laundry and small-scale manufacture undertaken by patients evoked the natural, therapeutic elements of work that were “more or less seamless with the economic needs” of the institutions that housed them. See Laws, 70-71. 13 See Clare Hocking, 2008. This is developed in greater detail in her dissertation on the development of British Occupational Therapy. See Hocking, 2004. 9 It is no coincidence that NSPOT was founded in the middle of the Great War, just weeks before the Untied States joined the conflict. Occupational therapy’s history in the United States and Canada predates this important turning point, however, 14 and it bears repeating here how early practitioners, including most of the founders present at Consolation House in 1917, drew inspiration from human struggles with late stage urban industrialization. As Judith Friedland has observed, they displayed typical Progressive-Era reformist zeal in their desire to find treatments for those injured by industrial work, and more then a few displayed a penchant for social housekeeping in their deployment of occupational therapy programs, targeting the poor, the chronically unemployed, the crippled and the mentally ill. Many were familiar with and cited ideas from, or drew from their own experiences with, Settlement House initiatives, new prospects emerging from the field of “Mental Hygiene”, and the aforementioned Arts and Crafts movement.15 Like Friedland, Virginia Quiroga has credited Arts and Crafts, with aligned groups such as the Country Life Movement, with provided early occupational therapists with an objective focus of their therapeutic efforts. Drawing historical attention back to the era of the Social Gospel, in fact, Quiroga notes the ways in which initiatives like the Emmanuel Movement in medicine, a church-based enterprise led by a group of New England-based physicians, sought to combine physical and spiritual healing.16 These linkages were, in turn, a longstanding justification for the work of patients in mental asylums. Many such researchers point to the history of psychiatry, and see asylum “moral therapy” as a starting point for historical analysis of OT’s origins.17 Occupational Therapy arose from a desire to schematize therapeutic craft work, and render a series of craft-related tasks on a scale of wellness, depending on how advanced the task was and how much creative energy went into performing the discrete actions. For many clinicians doing history, the quality of the work, and the creative activity of craft-making, differentiated the new orientation of occupational therapy from previous moral therapy work cures.18 Herbert Hall’s idea of a graded craft work, still used today, fits within this paradigm, while his work and idea about creativity have fallen by the wayside. Such thinking supported the emergence of industrial medicine. Alice Hamilton, a Harvard Professor in this field and a pioneer of what she called “occupational epidemiology” observed the devastating Its emergence in the UK during the interwar period, for instance, revolved around the institutionalization of programs by advocates like Margaret Fulton, a Scottishborn nurse who became Britain’s first qualified occupational therapist at the Aberdeen Royal Asylum. See Patterson, 2002, pp., 10-11. 15 Friedland, “Why Crafts?” 206. 16 Quiroga, 103, 105-107. 17 As Laws points out, these were bolstered by the fact that the gardening, sewing, laundry and small-scale manufacture undertaken by patients evoked the natural, therapeutic elements of work that were “more or less seamless with the economic needs” of the institutions that housed them. See Laws, 70-71. 18 See Clare Hocking, 2008. This is developed in greater detail in her dissertation on the development of British Occupational Therapy. See Hocking, 2004. 14 consequences on working class men. “[M]odern work is different from what our race has been used to for aeons,” she wrote, “…Now a great deal of work requires no skill, and the machine sets the pace and makes the man feel he is it’s slave, not it’s master. He loses pride in his work and his sense of individual importance.”19 Industrial medicine would not survive as as a distinct therapeutic field like occupational therapy, but Hamilton’s work in this field signals the medical profession’s engagement with worker health. Throughout America’s industrial era, counter-cultures of work have been designed and offered up by social workers and healers from a wide array of backgrounds as antidotes to the dangers and dehumanization of factory manufacture. Additionally, by the late nineteenth century, it became clear that the middle classes were also not immune to the ravages of industrialization, though otherwise removed from factory line work. Neurasthenia – a nervous exhaustion afflicting the better classes, also caused by overwork and over-civilization generally – had become the malaise of the era. This galvanized a leadership around the search for occupational solutions, including therapies, to problems linked to industrialization, but also loosely associated with “modernity.” As Jackson Lears has pointed out, “Arts and Crafts Ideologues…came usually from among the business and professional people who felt most cut off from ‘real life’ and most in need to moral and cultural regeneration.”20 Many craft leaders were self-styled “communitarians” who sought, through craftmaking, a solution to what they perceived to be a fragmented self, where psychic and physical well-being did not automatically go hand in hand.21 For this reason, many of occupational therapy’s first patients, including most of those treated by Herbert J. Hall, were neurasthenics. Accordingly, historians of the profession, especially clinician-scholars, commonly see the Arts and Crafts movement as the primary influence over the field, providing both the aesthetic and ethical impetus for early occupational therapy practice. Sociologist Jennifer Laws has observed how, as a profession, occupational therapists “both birthed and became safeguarders of such specifically therapeutic work…notions of a therapeutic occupation thus became a professional as well as philosophical investment.”22 Yet, within this diverse group of OT founders, it is unsurprising that we find a lack of consensus and several points of professional disagreement and debate about the intrinsic value of work as therapy. The professional training of practitioners, for instance, and what the methods and focus of training for new practitioners in the field should entail, preoccupied many Alice Hamilton, Exploring the Dangerous Trades: The Autobiography of Alice Hamilton (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1943), pp. 14-15. 20 T. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), p. 61. 21 Lears, No Place of Grace, 96. 22 Laws, 71. 19 founders and dominated discussions at Consolation House in 1917.23 Clinicians, were critical of the early aide’s lack of medical training, as they were hired for their craft expertise,24 but the reality was that craftsman-clinician collaborations were a common part of workshop planning and execution in the experimental era of early OT. According to Ruth Schemm, early experimental therapists who embraced and worked closely with artisans, like Herbert Hall were critiqued in absentia because they “did not embrace a unified value system” but instead “amalgamated” some biomedical beliefs with the aforementioned “humanistic values” inherent in Arts and Crafts.25 For Hall and practitioners like him, technical training was critical to effective occupational therapy because unlocking and supporting the creative capacities of the patient were essential to a restoration of health. New Zealand OT scholar Clare Hocking sees this focus on creativity as setting up an inherent conflict between “the romantic and the rational” elements of early occupational therapy work programs.26 This debate about training belied a deeper division within the field over whether it was “the process or the product,” to use Schemm’s formulation, that should occupy OT.27 The rational, systematized, scientific side of OT work, focused on assessing and grading the ability of patients to resume and perform occupational tasks, eventually gained ascendancy in the post-World War Two era at the expense of aesthetic, handcraft mastery.28 But how did his shift occur? Many clinician historians readily admit that a coherent set of ideas about occupational therapy, and an explanation for the abandonment of craft work, are difficult to The debate revolved around the question: should they be schooled in the principles and practices of scientific nursing or to develop an expertise in craft production itself, or both? Virginia A. Metaxas [Quiroga] describes how scientific nursing won the day in “Eleanor Clarke Slagle and Susan E. Tracy: Personal and Professional identity and the development of Occupational Therapy in Progressive Era America,” Nursing History Review 8(2000): 39-70. 24 Spackman, for instance writes how “personal qualifications” tended to trump any medical background, although most aides did have four months basic medical instruction. Nonetheless she writes how “the occupational therapists so trained were equipped as teachers of arts and crafts, and not as therapists.” C. S. Spackman, “A history of the practice of occupational therapy for restoration of physical function: 1917-1967,” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 22, 2(1968): 68. 25 Ruth Levine Schemm, “Bridging Conflicting Ideologies: The Origins of American and British Occupational Therapy,” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 48, 11 (November/December 1994): 1087. 26Clare Hocking, “The relationship between objects and identity in occupational therapy: a dynamic balance of rationalism and romanticism,” unpubished doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology, 2004. 27 Schemm, 1087-88. 28 See Clare Hocking, “The Way We Were: Thinking Rationally,” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 71, 5 (May 2008): 185-195; “The Way We Were: The Ascendance of Rationalism,” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 71, 6 (June 2008): 226-233. 23 explain. To further unpack this heritage, historians might well explore how the ideological evolution of occupational therapy may be reflected in the production of goods. A consideration of sometimes uneasy collaboration of craft and design experts, like Barton, and clinicians in early occupational therapy, such as Hall, also casts new light on the field’s “multifaceted heritage of caring.”29 The robust debates in the past about where to set the bar for patients in terms of the quality of the materials produced, and the early clinical obsession with market value of patients’ handicrafts and acquired skills. Thus the changing material production within OT workshops offers a means of assessing and contextualizing this moment in the history of therapeutic craft. While traditional occupational therapy and these early links to handicrafts are downplayed by clinician historians as part of the profession’s “romantic” beginnings, a social historian can, by contrast, make a clear link to a set of liberal-order therapeutics, wherein the health of the individual is treated with material engagement in a capitalist economy for handicrafts and agricultural productivity. To advance this historiography, I argue, we should move from the intellectual to the material history of occupational therapy, and revive old questions by asking them from a new perspective. What was produced in OT founders workshops? What value was ascribed to these objects? Wherein and in what conditions did it all come forth? Barton and Hall: The Case for Comparison Apart from the common link to early sheltered workshops, there are many other points of comparison that link George Barton and Herbert Hall together in any discussion of early occupational therapy, including their commitment to arts and crafts, their interest in vocational education, and the fact that both came to their interest in occupational therapy as patients. George Barton had a deep connection to the Arts and Crafts Movement, having served as Secretary of the Boston Arts and Crafts Society in 1904. As a young man, Barotn had worked at the Kelmscott Press in London, England where William Morris had done much of his calligraphy work and worked in bookbinding.30 Barton had had ample exposure to arts and crafts by the time he was was faced with a partially paralysis following the amputation of his left foot. Despondent at first, he recovered “full capacity” after following a work cure regime in carpentry during his own convalescence. Less than one year later, Barton opened craft workshops at Consolation House to “demonstrate the power of using goal-directed activities or occupations to cure persons with illness or disabilities.”31 While Hall’s own convalescence is shrouded in some mystery, we know from the writing of an early collaborator, Jesse Luther, that he was in upstate Suzanne M. Peloquin, “Occupational Therapy Service: Individual and Collective Understandings of the Founders, Part 2“ The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 45, 8(August 1991): 733. 30 Schemm, 1083. 31 Ibid. 29 New Hampshire taking a cure for an undefined disease when the pair met. It was during this period of taking a rest cure that Hall came up with the idea of opening a hand craft workshop at Marblehead and Luther, with training in both nursing and design, was one of his first employees.32 Among early proponents of OT, only Barton and Hall shared the roles of both convalescent and convert to work cure ideas, and, among early OT advocates, only they were so inspired with the prospects of therapeutic craft work that they opened private sanatoria for the purposes of advancing occupational therapy as a viable treatment for nervous, as well as physical, ailments. Both George Barton and Herbert Hall also had careers in OT that spanned the transition from therapeutic craft aimed at middle class debility to more general occupational interventions for average working men and women. When comparing the workshops of Consolation House and Devereux Mansion, it is striking the degree to which the material products of both men’s work programs changed over time. This, I argue, reveals the proletarianization of craft work within early occupational therapy. Early on, the products were traditional arts and crafts such as weaving, pottery, metalwork and basketry,33 although Barton also assigned patient referrals to Consolation House to the care of a large garden at the back of the building, as a sort of exterior workshop. As the workshops became popular, the emphasis moved from producing quality goods to more utilitarian and adaptive products. The popularization of occupational therapy by moving toward low-grade craft work is normally associated with the work of semi-skilled rehabilitation aides who were deployed during and in the wake of WWI, the concomitant need to treat and reintegrate massive numbers of wounded soldiers into the post-war workplace. Yet, when considering the work of Barton and Hall, the material reorientation of OT from middle class artisanal diversions to predated the focus on soldier rehabilitation. Instead, a shift in the material preoccupations of OT workshop outputs reveals how the broader social concern for industrial re-education and regeneration co-opted the radical elements of arts and crafts movement to serve the purposes of a liberal medical marketplace. According to Jesse Luther, she and Hall met while convalescing at a quasisanitarium called the “Ark” in New Hampshire over 1903 when both were convalescing from illness. The nature of the illness is not mentioned. Ronald Rompkey, ed., Jesse Luther at the Grenfell Mission (Montreal and Kingston: McGillQueen’s University Press, 2001), p. 7. Rompkey clarifies in his note that this was not as such a sanitorium, but a popular middle-class mountain hotel where many went to recover form a variety of illnesses. Rompkey, 7, fn.1. 33 Collins, 1906. 32 Creating Consolation House Born in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1871, George E. Barton was trained as an architect in London, and worked out of Boston Massachusetts in his early years.34 For a time, he was affiliated with the Boston Society for Arts and Crafts35 and many sources claim he was a charter member.36 After suffering a difficult bout of tuberculosis in 1901, he went to Colorado to take a mountain rest cure and recover. In remission, he took up residence in the area, and pursued several design commissions in Colorado, including a new sanatorium in Colorado Springs. Although it seemed his health had been restored, Barton suffered a second blow. He suffering frostbite following a trip to Kansas, he had to get his left foot amputated when it became gangrenous. This setback resulted in what he called a “break in health,” an episode that caused partial paralysis on one side of his body.37 Unable to pursue his career in industrial design, he retired to upstate New York, choosing the quiet spa town of Clifton Springs as a location for his recuperation. 38 Clifton Springs was home to a Tuberculosis Sanatorium, and Barton found the respite he sought within these walls. At the time, the chosen treatment for tuberculosis patients was rest, ample nutrition, and fresh air. While taking the spa waters and convalescing, he got to know Reverend Elwood Worcester, who introduced him to a type of recuperative therapy that engaged occupation. Worcester was a key figure in the aforementioned Emmanuel Movement, an early 20th century Boston-based regime that combined spiritual counseling with psycho therapy to treat functional diseases, including tuberculosis, among the poor.39 A key concept of the Movement was that treatment should engaged mind, body and spirit.40 Chafing under the restrictions of the prescribed rest regime, Barton adapted Worcester’s ideas and undertook a selfdesigned program that combined outdoor activity, carpentry and garden work with his convalescence. Within the year after adopting such “active rest” he retained almost full use of his left side, and became a convert to the idea of active recuperation. With the zeal of a new convert, he engaged in an enthusiastic and entrepreneurial correspondence with physicians active in the fields related to Isabel Newton Barton, “Consolation House,” c. 1918, unpublished paper, Consolation House collection, Foster Cottage Archives, Clifton Springs, New York. 35 Newton Barton, c. 1918. 36 Quiroga, 116-117. 37 Quiroga, 117. 38 Samuel Hawley Adams, Life of Henry Foster, M. D. , Founder of Clifton Springs Sanitarium (Rochester, NY: Rochester Times-Union, c. 1921), pp. 16-22. 39 The founders wrote, for instance, “We believe in the power of the mind over the body, and we believe also in medicine, good habits, and in a wholesome, wellregulated life.” Elwood Worcester, Isadel Coriat and Samuel McComb, Religion and Medicine: The Moral Control of Nervous Disorders (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1908), p 2. 40 For further information on the Emmanuel Movement, see Sanford Gifford, The Emmanuel Movement: The Origins of Group Treatment and the Assault on Lay Psychotherapy (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1993). 34 rehabilitation, striking up a close working friendship with William Dunton.41 At the same time, he undertook to spread the word about how the “tonic” of work speeded convalescence. He bought a house and small tract of land in Clifton Springs in 1914, which he quickly converted to a workshop retreat where other convalescents could engage in work cure programs, and called it Consolation House (See Figure 1: Consolation House, c. 1917). It was in the course of his correspondence with William Dunton that Barton inadvertently coined the term “occupational therapy.” Writing in 1915, a year after Consolation House opened about the problems of recuperation for injured and incapacitated industrial workers he posed the question: “If there is an occupational disease, why not an occupational therapy?”42 In healing himself of his paralysis in Clifton Springs in 1914, Barton “used his own body as a clinic to work out the problem of rehabilitating himself.”43 In an unpublished memoir written by his wife, Isabel, the narrative of his work cure programs lays out, in great detail, Barton’s conceptualization the body as a site of therapeutic labours and how it should interact with material objects and draw inspiration from the material environment. Originally, Barton had a multi-purpose vision for the site. Both the philosophy and the aesthetic of Arts and Crafts were prominent at Consolation House; by most accounts the home was littered with beautiful and the useful items from the Mission style. Importantly, one of the first rooms completed and made available to referrals was a room outfitted with a hand loom and several small-scale carpentry tables. (see Figure 2: Consolation House Workshop, c., 1915) His retreat soon fulfilled many functions, all in service to his approach to therapeutic work. With the expansion of the gardens, the agricultural component of his occupational therapy became foregrounded. While there were areas for sewing, weaving and metalwork, the focus of activity was increasingly the carpentry work room, where Barton taught the precepts of industrial modeling (see Figures 3, 4: Workshop at Consolation House, c. 1915). Barton was also a proponent of fresh air, and he put the visitors to Consolation House to work in the fields and the outdoor studios, where they also busied themselves in basic carpentry. According to several sources, he became familiar with Herbert Hall’s work at Marblehead, and came to adopt Hall’s framework of “grading” occupations. He also gradually adopted energy conservation strategies alternating periods of work with equal periods of rest. George Barton defined the patients’ roles at Consolation House. Adopting the title of “Director”, Barton took on a hybrid role in the treatment of patients under his roof: one part clinician44 and one part vocational educator. These combined in Quiroga, 119. Reed and Sanderson, 1999. [get page] 43 Newton Barton, 1918. 44 Quiroga draws attention to several publications where he appropriated medicalscientific language and modeled diagnostic activities. She notes that this overstepping of professional boundaries that could well have been seen as “patronizing” to clinicians. Quiroga, 119-120. 41 42 determining the orientation and level of patient work. While not his own “patients” in a strict sense—those participating in occupational therapy at Consolation House were individuals were mostly sent to him by physicians—occupants understood that Barton would determine the course of occupational therapy. He would begin by assessing the patient’s education, as well as the status of her or his convalescence, and both the clinical prognosis as well as the patients’ own “habits, ambitions and expectations for recovery and post-recovery.” 45 Assessing the ambulatory status, manual dexterity and assessing what degree of physical activity the patient could bear determined the set up of work space and the assignation of tools. 46 But, as above, Barton also sought to improve the physical, mental and spiritual aspects of the patient by uncovering occupations that were meaningful to them. Often, these were derived from his previous line of work, so the patient could reconnect to former productive lives led before the injury. Both considerations could, in Barton’s view, “effect analgesic benefits” and shorten convalescence in a manner “similar to a drug.”47 While he did not lay claim to clinical expertise, Barton saw himself as a holistic practitioner engaged in the restoration of health. The expertise upon which his authority rested was his ability to “treat” his patients by determining specific work projects, providing creative spaces tailored to the occupation, and, most significantly, providing set of adapted tools that would enable the occupation and facilitate recovery. In several publications, Barton sees the materials of labour—the toold-- as the element that provided “therapeutic advantage.” What he described as his “Material medica” constituted “a hundred page catalogue of tools and machines.” It was from “a visualization of each…[that Barton] ‘compunds’ [sic] his ‘prescription’ in much the same way as does the physician save by ‘physics’ instead of ‘physic.’”48 The clientele of Consolation House were initially middle class and Barton admitted individuals recommended by clinicians from the area. In the early years of operation, most the patients were drawn from the ranks of the middle classes, most of whom were recovering from tuberculosis and were referred from the Clifton Springs Sanitarium, famous for its water cure treatments, and where Barton himself had undertaken a rest cure post-amputation.49 Gradually, however, Barton’s goals coalesced around a larger social goal: to provide individuals suffering from industrial and other accidents with a space to convalesce and “reeducate” their minds and bodies. Over 1915-1917, the workshops’ organization and productive purpose were reframed. Not only would active occupational therapy seek to speedily restore patients to health, but to also give them meaningful and productive George E. Barton, “Inoculation of the bacillus of work.” Modern Hospital 8(1917): 399-403. 46 Newton Barton, c. 1918. 47 Barton, “Bacillus of work.” 48 Newton Barton, c. 1918. 49 Quiroga, 117-118. [cite materials she cited] 45 lives after recovery, and become “re-educated” for work. Eventually, according to his wife and biographer, Irene, “it acted as a school, workshop and farm…an agency for vocations.” His ideas had considerable impact on the new and emerging field of Occupational therapy. Barton provided a good deal of the organizational energy to the professionalization of OT, particularly providing energy and leadership during the early years of NSPOT. He not only took on the inaugural presidency of NSPOT, but also served as the new organization’s chair of the Committee on Research and Efficiency, where he collaborated with foreign efficiency engineers among the Allied forces who helped rehabilitate wounded soldiers. Barton helped establish the connection between OT and wartime physical rehabilitation and this role influenced the shift in his workshop’s orientation. Many of these correspondences are captured in his 1917 publication, Teaching the Sick. Through an analysis of these writings, it becomes clear that, by the end of his career, Barton came to place greater therapeutic value in the accrual of skills more so than the creation of a crafted object. Nonetheless, Barton remained committed to the broader goal of capacitybuilding for men injured by industrial work. Perhaps drawing from his own experiences as a temporarily disabled professional man, his interest was continually drawn back to the special material needs of men injured in industrial accidents. The “re-education” of such men, a word he borrowed from the rising field of vocational education, became the primary object of his writing and his retreat became finding a place for them gradually took over the workshop activities at Consolation House. Although the timing of this transition and reorientation in Barton’s work roughly coincided with the outbreak of WWI, the rehabilitation of wounded soldiers was simply a slight reorientation of established programs for male victims of industrial accidents. “With the daily press and the magazines overflowing with illustrations of what the crippled of war are accomplishing for self-support, it is easy to overlook the less spectacular but no less important activities of the crippled of peace…, “ he wrote in 1916.50 And the goal of his OT program was twofold, to re-educate patients to take on a “better job” than the one that debilitated him, but also to cultivate the capacities and skills that would allow for a “job done better.”51 The program was highly gendered, and geographically targeted. Barton became increasingly fond of claiming that engaging in such creative endeavours would be “the making of a man.”52 He saw the “invalid occupation” of arts and crafts, pursued as a form of convalescent distraction in many military hospitals of the day, as nothing more than “rubbish.” Instead, he advanced an OT program that promised “men’s work for men’s pay,” even though many patients who would use OT and reeducation might suffer significant debility that prevented them continuing with Barton, Teaching the Sick: A Manual for Occupational Therapy and Recreation (Philadelphia and London: W. B. Saunders, 1919), p. 137. 51 Barton, Teaching the Sick, 64. 52 Ibid. 50 their former occupation.53 The cultivation of a man’s “will” was of paramount importance. In Teaching the Sick, he offered inspirational stories from heroic children to make his point, profiling the stories of Helen Keller and Alva Bunker, disabled youngsters who were, at the time, triumphing over disability and learning lead active and productive lives despite blindness and severe congenital deformity.54 For Barton, the ideal triumph of the injured worker or soldier resulted in a “return” to life on the land, regardless of whether the individual came from a small town or farm. Barton had taken an interest in rural life well before opening Consolation House. In fact, it was in the course of researching the causes of famine among Kansas farmers in 1914 that he suffered frostbite that resulted in his foot amputation.55 For Barton, promoting agricultural life in America allowed him to continue supporting key arts and crafts philosophies. The celebration of rural, agrarian life and it’s ability to “make a man” informed the transitions in his workshops toward model drafting, basic design and carpentry. The prescriptive re-education program he advances in Teaching the Sick describe the material conditions and products of these newly redesigned workshops as his refined regimes focused on teaching the practical design of buildings and infrastructure to support small-scale agricultural pursuits. 56 Over the course of several chapters, he lays out a program of reeducation that follows the principles of industrial design education, remediated for the layperson with varying technical abilities. Barton introduces patients to the principles of draft design on paper, with the gradual integration of modeling with clay or wax. Then, an introduction to the use of tools adapted to the patient’s strength and the nature of the disability, skill development of such topics as joinery, to the construction of model buildings and other simple objects using scrap wood. Most often, these tasks lead up to the performance of basic carpentry on a real life In a 1919 report on soldier rehabilitation, the Federal Board for Vocational Education ridiculed many programs of invalid occupation as merely the production of “alleged ornaments.” Instead, the Board called for “specialized programs” offering good pay in “manly callings…definite , useful place in the business world.” Qtd in Barton, 59. 54 Alva Bunker’s case highlighted, according to Barton, an example of someone distinctly “uncrippled” in will. Barton, Teaching the Sick, 138-139. Barton, like many interested in vocational education, was inspired by the Michigan Hospital School’s work with disabled children. For context related to the Alva Bunker case in particular, and Barton’s role drawing attention to and advancing the Crippled Children’s Movement see Barbara Floyd, “The Boy Who Changed the World,” Ohio History 118(2011): 77. 55 Quiroga, 117. 56 The primary focus of his background research draws from the French government’s programs in creating sheltered agricultural enterprises, such as poultry farming. See George E. Barton, “The Therapeutic Value of Squab Raising,” Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 60(February 1918): 65-74. 53 scale.57 The showpiece of his reinvented program by 1918 was the Consolation House Carpenter Shop, a specialized workshop with “a whittling tray fitted with a vise, bench stop and mitre box so arranged as to fit the needs of a wide range of disabilities.” Emphasizing the “true value” of the workshop for serious skill acquisition, Barton took pains to explain that while they were offered for the construction of wooden models, these were to be considered adapted tools. Smaller and somewhat lighter than their standard counterparts, they were nonetheless “in no sense toys” and the scrap wood and fasteners were to be called by their life-scale counterparts (sill, boarding, bolts, etc.).58 By mimicking the forms and conditions of on a small scale, Barton attempted to combine re-education with conditions that promoted a return to full physical capacity, or at least improved, physical capacity.59 In addition to providing a means and method to encourage exercise, the workshop instruction highlighted a particular material relationship to the means of production. This is most clearly articulated in Barton’s at times lyrical and often animistic description of the workshop tools and how they should be understood, related to, and ultimately used by an occupational therapy patient. “Tools,” Barton insisted, were “very much like humans.”60 And learning to work with them meant cultivating a sensitivity to their form and function. Key to an assessment of their proper use was to listen for the proper sounds that emanated from a well-run carpentry shop. By “humanizing” each tool in carpentry re-education, the shop became a site where the hatchet and chisel elicited a “contented crunching” and the hacksaw offered “the contented grown of a hungry kitten” when properly deployed.61 Describing the tools and relationships to tools in such a manner gave Barton’s text on re-education more than poetic impact, it placed his prescriptive OT in a political position where artisanal work is depicted as harmonious, even harmonic, and, therefore, also healthy. A patient’s prognosis could be determined and expectations for recover could be gauged by analyzing the conditions of work in this way. For Barton, “the sound of the tool” was the best indication of where the For these step-by-step program, see, for instance, Barton, Teaching the Sick, 72-75 [mechanical drawing], 94-95 [chip carving], 102-103 [clay and wax modeling], 106119 [using woodworking tools like the t-square, mitre and plane], 124-127 [joinery], 130-133 [carpentry]. 58 Barton, Teaching the Sick, 126-127. 59 He clarified in his section on woodworking, “The primary object is not to induce the sick man to make something: it is to tempt and to teach him to do something which will necessitate such motions and activities as will be conducive to an improved condition. Invalid Occupation there may be in tempting or allowing the patient with a stiff right knee to run a jigsaw: Occupational Therapy cannot be conceived to have begun until the patient is endeavouring to break out, to limber up his stiff right leg, which on the jig-saw might be accomplished with a bicycle tread. Barton, Teaching the Sick, 119. 60 Barton, Teaching the Sick, 108. 61 Barton, Teaching the Sick, 109. 57 patient stood on the road to recovery. “All good tools, like all good men sing at their work when properly treated,” he wrote.62 There was certainly the expectation that these sheltered re-education workshops, and the Consolation House Carpenter Shop in particular, prepared the residents for real life application of these skills. Barton claimed success from many projects in small-scale construction. Pointing with particular pride to a “pigeon house” constructed as a final exam in carpentry by a female patient, Barton describes how the young woman had arrived “unable to work in the shop without fatigue for more than two hours daily.” Nonetheless, he wrote,” within three months her strength was so increased that she was able to work for six to eight hours a day in summer weather out of doors.” Carpentry elicited physical improvement, but Barton praises equally the skill acquisition that went along with her recovery, noting how, ‘The entire building was designed, drawn, estimated, and built within the estimate by her with practically no assistance, and is true, plumb, and square.”63 Barton thus saw “reeducation” of the sick as an emerging science. Yet, as he himself pointed out, it was a therapy in search of a method and praxis. While only offering what he called “the basest of outlines” in his manual on Teaching the Sick, we nonetheless see a systematized process that combined active, creative convalescence and skillbuilding. While highly descriptive and not formally theorized, his prescriptive steps carefully considered both the physical and mental processes at work at different stages of recovery, all based on careful empirical observation at Consolation House-“comprehensive data” of his own researches.64 Before his death in 1923 from a recurrence of tuberculosis, Barton had laid the foundation for a complex, evidencebased in scientific observation and experimentation as the field progressed. Herbert Hall: From Handicraft Workshops to Medical Workshops Herbert J. Hall was born in a mill town in New Hampshire in the spring of 1870, the son of an accountant. He graduated from Harvard Medical school in 1885, and after an internship and a brief rotation in orthopedics at Children’s Island Hospital,65 he opened up a general practice in Marblehead Massachusetts. Marrying into the wealthy and well-connected Goldthwaite family, Hall was able to open up a sanitarium in 1905 with the financial support of his wife’s family, and financed his early activities treating neurasthenia with two Proctor Fund Grants provided by Harvard Medical School.66 Here, in what he called “practical protest” to the hegemony of the rest cure in the treatment of neurasthenia, Hall began experimenting with a work cure in the workshops of his Handcraft Shop at Devereaux mansion, where patients engaged in “pleasant and progressive Barton, teaching the Sick, 106. Barton, Teaching the Sick, 133. 64 Barton, Teaching the Sick, 139. 65 citation 66 Each grant was $1000, awarded in 1905, when he opened the sanitarium and 1909. Hall Anthony, “Herbert J. Hall, Part 1,” 7. 62 63 occupation.”67 Herbert J. Hall’s “work cure” for neurasthenia was hailed as an ‘epoch-making” by the elite physicians of the day.68 While historians tend to depict Hall’s thinking in static terms, however, his ideas about occupational therapy actually changes considerably over time. In the early years of his workshop programs at Devereaux Mansion, he prescribed craft work to his female patients to restore the “courage and self-control” necessary to overcome nervous diseases like neurasthenia.69 Yet, by the time his workshops had expanded into pottery, his ideas about the internal “work on the self” that accompanied handicraft therapy equaled, in his mind, by the social approval and economic independence that came with skilled craft acquisition. In his early handicraft workshops, set up in a converted yacht club, Hall began his work with neurasthenics need treatment but in “fair” condition. Mostly women, these patients were housed a few hundred yards away from this practice in a nearby boarding house.70 There, engaged in mainly weaving activities, female neurasthenics took up therapeutic craft as a new form of active rest [see Figure 5, middle class woman bent over a loom, c. 1910). When he purchased the Devereaux Mansion a few years later, this allowed Hall to expand both the patient base and the range of activities associated with his “work cure.” The Mansion came with a large barn, which, with its tall windows on each end and balconies, was easily adapted for craft industries.71 (see Figure 6: Devereux Mansion barn, c. 1917) Local press dubbed it the “made-over barn where the ill are made over.”72 This provided a good site for the sale of handicrafts items, and it was not long before a variety of wares were offered up, both to support of the patients and their treatment, as well as to provide for the upkeep of the Devereux Mansion itself. While he was an enthusiastic self-published poet, Hall was no crafter, and he relied on skilled artisans with formal training to oversee the production of patients’ crafts. These were mostly young women whom Hall took under his wing and gave employment and inspiration. Hall envisioned they would take the work cure principles and teach therapeutic crafts in schools, sanatoria and hospitals. One wellknown associate was Jesse Luther, mentioned in previous pages, a young woman This was part of a paper presented before the Massachusetts Medical Society in Lynn, 1904. See Herbert J. Hall, “ The systemic use of work as a remedy in neurasthenia and allied conditions,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 152(1905): 29. The Sanitarium was called “handcraft shop” to remove the therapeutic association with sanitarium.” 68 See Richard C. Cabot, “The ‘work cure,’” Times (October 12, 1914). 69 Hall and Buck, xxiv. 70 Letter. Herbert J. Hall to Frederick C. Shattuck. January 21, 1905. Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, MA. qtd, in Hall Anthony. 71 G. P. Hercher, “The work cure at Devereaux Mansion,” Essex Institute Historical Collections (Salem, MA: Essex Institute, 1980), p. 106. 72 “The Made-over Barn Where the Ill are Made Over,” The Sunday Herald Magazine (September 22, 1912). 67 trained in art, weaving, and industrial design as well as nursing who eventually made a name for herself associated with the Grenfell Mission.73 But she was not alone. According to Hall, he attracted and trained 63 artisan apprentices over the first fifteen years of his work cure programs, who he brought in for their technical expertise.74 While Hall did not pretend that hand looms could compete with machine looms, either in the scale or quality of some items derived from their operation, the “charm and interest” produced by hand woven goods made them desirable market objects,75 able to compete in niche markets for handicrafts that were popular items in New England at the time.76 In his first of many book-length publications, The Work of Our Hands, Hall explains how the skilled craftsmen collaborate in the production of saleable goods by providing “special patterns and individual effects” which added value to the final produce. 77 With materials that cost 60 cents, for instance, baby blankets produced over a day and a half in Marblehead weaving workshops sell for five or six dollars.78 At Devereux Mansion the site of therapy was also the point of sale. The craft work drew considerable attention and saw early commercial success. A most famous by product of these workshops is the highly collectable line of Marblehead Pottery, art nouveau-inspired ceramics designed by craftsman Arthur E. Baggs, one of Hall’s first employed artisans and the most famous.79 While Baggs and the Marblehead pottery line soon split from Hall’s therapeutic endeavours, the association helped secure the reputation of Hall’s work cure, as a therapeutic regime that promised economic success in additional to therapeutic promise.80 By 1913, Hall’s workshop programs were no longer solely engaging neurasthenes, and were increasingly more generally designed for “handicapped” populations. This precipitated a slight reorientation in the material output of his occupational therapy program. By focusing on the “special needs of disabled workers” Hall became the inspiration for the establishment of similar workshops, including tile and cement factories for heart patients in Connecticut and high-end pottery studios for tuberculosis sufferers in San Francisco.81 By the time the First World War broke She was eventually recruited to the Grenfell Mission in Newfoundland and Labrador. See Rompkey, 7-9. 74 Letter. Herbert J. Hall to William Dunton, September 2, 1921. AOTA Archives, Wilma West Library, Bethesda, MD, 2. 75 Herbert J. Hall and Mertice M. Buck, The Work of Our Hands (New York: Moffatt, Yard and Company, 1915), pp. xxiii-xxiv. 76 Cite material on arts and crafts epicenter in New England. 77 Hall and Buck, The Work of Our Hands. 78 Ibid. 79 Herbert J. Hall, MD, “Marblehead Pottery,” Keramic Studio 10, 2 (June 1908): 30. 80 By 1909, for example, Hall had discontinued teaching pottery at the sanatorium due to fears that it was too hard for patients to manage the frequent accidents with the pots. Reed, 35. 81 Lilas Hardy and Kathleen Schwartz, “Philip King Brown and Arequipa Sanitorium,” Early Occupational Therapy as Medical and Social Experiment,” 73 out, Hall had closed his original Handcraft workshop and, while the he continued to enjoin his middle and upper class female patients in hand-waving and rug-hooking, opened a “Medical Workshop” on the grounds to take its place as the centerpiece experimental site on the Devereaux Mansion estate. In the new “Medical Workshops” he continued to focus on weaving as a key therapeutic endeavor. Weaving was easy to organize and oversee. But Hall discarded pottery-making in favour of cement ware manufacture, since it required less skill and could be produced more quickly than kiln-fired clayworks. Both came with the added benefit of assisting patients with physical incapacities to earn a living from the sale of craft items. The commercial success of the material goods produced at Devereux Mansion was fleeting, and largely disappeared with the removal of Arthur Baggs from the premises. Writing in a special 1917 issue of Modern Hospital on the subject of occupational therapy, Hall still put much emphasis on the production of quality goods in the therapeutic workshops, but he no longer emphasized the quality of the material goods as much as in the early years of his operation. “After some thirteen years experience with therapeutic occupations, “ he wrote, “it is very plain to me that… the more useful the work, the better its therapeutic effect.” Here the emphasis falls on the “utility” of the object rather than its beauty and “charm” and market value. Mere distraction was insufficient to work on the recovery. And Hall continued to claim that “the more trivial and valueless the product of the work, the less effective will it be in the therapeutic sense.”82 A decade and a half into the experiments with occupational therapy, however, Hall was growing tired of the production of material goods he now described as “so-called arts and crafts.” Writing more critically in 1917, he cautioned other OT enthusiasts not to expect too much from the “eager young women” whose craft work as patients he found would not succeed in any commercial sense without the support of skilled artisans in the field. The point became less about excelling in craft making to assist in earning a livelihood, but also to “restore strength, skill and confidence.”83 By this time, Hall admitted that developing a practical framework of marketing the wares produced in hospital, sanatorium or asylum occupational therapy workshops was beyond the ability of a therapeutic workshop. This would not negatively affect the bulk of his particular practice. “Most of my patients,” he explained, “are well-to-do.”84 Hall claimed success, however, in placing these patients as OT professionals in the rapidly expanding 20th century hospital system. Most of his former middle class American Journal of Occupational Therapy 67(2013): 11-17. See also Philip King Brown, “The Potteries of the Arequipa Sanatorium,” Modern Hospital 8, 6 (June, 1917): 394-396. 82 Herbert J. Hall, “Remunerative Occupations for the Handicapped,” Modern Hospital 8, 6(June 1917): 383. 83 Hall, “Remunerative Occupations,” 386. 84 Hall, “Remunerative Occupations,” 385. female charges, he claimed, were “earning their living, not as producers, but as teachers and supervisors in hospital, sanatorium, or asylum shops.”85 The purpose of the objects produced also shifted focus changed. The “beautiful products in woven fabrics and cement ware” continued to take pride of place in Hall’s later publications, as these were still produced to sell. 86 Woodworking was also a new focus of production at the Medical Workshop, which employed increasing numbers of working class women and men from nearby industrial centre of Lynn and Salem. Toward the end of his career, as Hall became actively involved in advancing and professionalizing occupational therapy, he envisioned the therapeutic craft work as a broader panacea for patients in hospitals and asylums, “where people of small means may have benefit of regulated work.”87 Hall capitalized on the expanded enthusiasms for OT in clinical settings. The last set of objects for which Hall’s enterprise at Devereux mansion became known was a line of wooden toys, but these were therapeutic objects. Partially assembled and roughhewn, they were made to be sent out to occupational therapy patients in other institutional settings to finish assembling, varnishing and painting at other institutions. Thus, by the end of his career, Hall’s workshops supplied the basic components of occupational therapy work in other hospital’s workshops. While there was some debate within OT circles about whether such low skill, last stage manufacturing in fact infantilized patients,88 Hall reported a brisk business for this latest incarnation of his occupational therapy programs.89 Hall was increasingly be drawn into the NSPOT orbit, and in his final years worked with Barton and others as a tireless advocate for the practice of OT, eventually to serve as an NSPOT President from 1920 to 1923. Under his tenure, the organization changed its name to American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Until his death following complications of surgery in 1923, Hall was determined to maintain the holistic mind, body and spirit interconnectivity in occupational therapy.90 Not that the physicality of the therapies went unnoticed. As Laws notes, Hall’s constant among the various therapeutic craft endeavours at Devereux Mansion was weaving, using an ‘old-fashioned hand-loom’ that provided Hall, “Remunerative Occupations,” 385. Hall, 1916. 87 Hall, 1916), p. 8. 88 Dunton, 1923. 89 He wrote in 1920 that “we are having a beautiful time shipping donkeys, pigs, lions, chickens, giraffes, crocodiles, east, west, north, and south… Hall, 1920), p. 2. In response to Dunton, he argued the helplessness of illness had a “softening influence” on a given patient giving them an appreciation for the play involved in toymaking.” Hall, 1923, p. 31. 90 According to See Hall Anthony, this was “much to the frustration of others, such as Dunton and Barton, who felt such language compromised the medical accreditation they sought for the new field.” See Hall-Anthony, “Part II.” 85 86 patients with ‘general exercise in strong and effective motion of arms and legs’.91 Yet, like Barton, Hall was increasingly concerned with the material output and the material laboring conditions themselves. With the opening of his Medical Workshops, Hall was intent on providing a material and social environment that facilitated creativity, that being integral to a holistic therapeutic regime. In this way, while the two men seemed sometimes at odds in the orientation and output of their respective workshops, their transitions from arts and crafts idealists to pragmatic advocates of occupational therapy within a liberal industrial framework places them on the same page of history within these early important years of the new profession. Conclusion As early OT advocates, both Hall and Barton derided the principles of mere “invalid occupation,” where craft-making is a distraction during convalescence, and sought to develop a broader, holistic vision for occupational therapy. While there is an obvious influence of arts and crafts revivalism in their endeavours, particularly early on, this paper has shown how the history of the new profession quickly expanded beyond that movements’ social and economic utopianism. For both men, the goal of occupational therapy in a community workshop was to create an environment where creative expression could foster convalescence by stimulating patient confidence, and engage in therapeutic “re-education” that would eventually enable active reintegration into the wage economy. The tendency among historians to date to focus on the philosophical underpinnings of occupational therapy draws attention away from the rich material cultures of the new profession. The changing products and material output of the experimental workshops run and operated by Barton and Hall offer key insights into the ways in which early therapists struggled to mesh their therapeutic idealism with the real rigours and demands of artisanal-quality work. Few patients at Consolation House or Devereux Mansion took away the type of skills that would sustain them as artisans. Yet this should not necessarily be seen as a material failure of early OT, as it provided both practitioners with insights into the value of creative occupation (as opposed to mere distraction) as a holistic therapeutic regime. Although Hall’s early writings show more of an arts and crafts revivalist orientation, this would change over the course of his career, with the transformation of his workshops from sites of “handicraft” production for sale to the public, to “medical” sites of production of materials for other clinical settings. Barton’s gave up the focus on rejuvenating rural America and re-instilling values of “rural self-sufficiency,” and instead focused on adaptive technologies and tools required of Occupational Therapy treatment, especially for the disabled. Both men were eventually forced to discard the idea that their patients’ work during OT would eventually allow them to be economically selfsustaining within an industrial capitalist economy. The material focus of work Hall’s 1915 book, The Work of the Hands, discusses at length the physical, tactile, bodily therapeutics of manual labour. (Hall, 1910: 13). Qtd in Laws, 72. 91 shifted from the material object to the material environment of the occupational work, as both men narrowed their focus on cultivating the beneficial pre-industrial work rhythms and occupational orientations of the artisan. They did this without necessarily expecting the artisan’s quality output from the workshop’s labours. Focusing on the material cultures of the workshops brings the otherwise disconnected narratives of Hall and Barton closer together. While not close colleagues, Barton and Hall were close contemporaries in the emerging project to advance and professionalize OT. Yet, in mutually reinforcing ways, both participated and directed a philosophical and material shift in early thinking about occupational therapy. Both practitioners expressed early enthusiasms, and then deep ambivalence, about the pursuit of such therapeutic endeavor within an industrial capitalist framework. The workshop environments that emerged at Consolation House and Marblehead and their changing material output, offers evidence of a paradigmatic shift within the profession concomitant with the change in emphasis from work cure to occupational therapy. This shows us how occupational therapy, at its material foundations, is a therapeutic regime founded on a rejection of the industrial complex as a framework for assessing and grading convalescence. Yet, in “creating” objects and environments for health, both oriented their workshops to service the wider health care economies of convalescence and rehabilitation emergent with the medical industrial complex.