Stomas of the Small and Large Intestine: Introduction - Dis Lair

advertisement

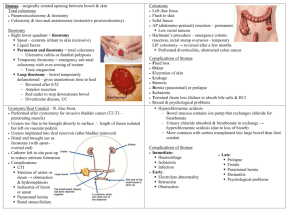

Stomas of the Small and Large Intestine: Introduction The use and management of GI stomas in children have evolved since the early success with colostomy formation in the 1800s. Improved surgical techniques, better understanding of the physiologic and psychological consequences of intestinal stomas, and advances in stoma care have contributed to more rational use of ostomies by pediatric surgeons and a wider acceptance in the medical and lay communities. Nevertheless, treating a child with multiple abdominal stomas can be intimidating and challenging (see the image below), especially when the anatomy is not clear and the fluid and electrolyte abnormalities are difficult to control. Multiple stomas in the abdomen of a 3-year-old child who underwent surgery as an infant for high imperforate anus. A divided colostomy was performed to divert the stool. The other end was brought out through the skin (mucous fistula) to allow evacuation of mucus and gas. A vesicostomy was performed because of a neurogenic bladder. Several differences between adult and pediatric ostomies are recognized. Most stomas in adults are formed in the distal ileum or colon for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, malignant conditions, and trauma; more proximal stomas are only rarely created. In contrast, stomas in infants and children may be required anywhere along the GI tract because of the wide variety of congenital and acquired conditions that require stoma formation. The effect of a stoma on physical and emotional development and on growth is an additional consideration in children. Although great advances have been made with regard to stoma formation and management, both early and late complications are common. Fortunately, most pediatric stomas are temporary, and many of the complications associated with intestinal stomas are eliminated when the stoma is closed. Understanding enterostomal construction and physiology is essential for providing these children with optimal care. History of the Procedure Colostomies were used in the late 1800s to treat intestinal obstruction. Some of the earliest survivors were children with an imperforate anus. Intestinal stomas were considered a drastic procedure and were avoided because of the high incidence of complications and mortality. With improvements in surgical technique and practice, the need for stomas increased as children with formerly fatal conditions survived. Problem Pediatric ostomies include any surgically created opening between a hollow organ and the skin connected either directly (stoma) or with the use of a tube. In infants and children, stomas are used for various purposes, including access, decompression, diversion, and evacuation. As a rule, most ostomies are for temporary use and are typically reversible in children. Certain medical conditions may dictate the need for a permanent stoma. Frequency The frequency of intestinal stomas is difficult to determine in the pediatric population. Etiology Many diseases may require a stoma or placement of a tube within the bowel. Small bowel stomas are used for patients with intestinal perforation or ischemia in whom an anastomosis is considered unsafe. A proximal ileostomy is often used to protect the distal anastomosis after restorative proctocolectomy for familial polyposis or ulcerative colitis. Similarly, colostomy is often used both before and after a pull-through procedure for imperforate anus or Hirschsprung disease, although many surgeons are now performing primary pull-through procedures without colostomy for both of these conditions. Tube cecostomy or Malone appendicocecostomy have been used for antegrade bowel irrigation in children with intractable constipation and various medical conditions. Children with severe perineal burns or trauma (see the image below) often require a temporary colostomy to allow the injury to heal. Severe injury to the perineum and anal sphincter (caused by a lawn mower) in a 9-year-old boy. A diverting colostomy was performed. Several weeks later, a skin graft was placed over the defect. After reconstruction of the anal sphincter, the colostomy was reversed. Patients with the following conditions may require a stoma: 1. Neonatal conditions Necrotizing enterocolitis Hirschsprung disease Meconium ileus Imperforate anus Complex hindgut anomalies Intestinal malrotation Intestinal volvulus Intestinal atresia, stenosis, and webs Esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula Trauma 2. Childhood and adolescent conditions Trauma Inflammatory bowel disease Intestinal malrotation Intestinal volvulus Gardner syndrome and other intestinal polyposis syndromes Typhlitis Intestinal pseudo-obstruction Pathophysiology The pathophysiologic features depend on the specific disease process. Presentation The clinical presentation depends on the specific diagnosis and age of the patient. Indications For an end stoma (see the images below), the bowel is divided, and the proximal end is brought through the abdominal wall. The distal nonfunctioning limb can be brought out through the same abdominal wall opening as the end stoma (ie, double-barrel stoma), it can be brought out through a separate incision (ie, mucous fistula), or it can be closed and left in the peritoneal cavity (ie, Hartmann procedure). When the distal segment is left inside the abdomen, many surgeons fasten it to the abdominal wall adjacent to the end ostomy or tag it with a nonabsorbable suture to facilitate identification when the stoma is reversed. A loop stoma is created by maturing a segment of bowel over a rod or tube without completely dividing the bowel. Stomas are used in situations in which diversion of, decompression of, or access to the bowel lumen is needed. Relevant Anatomy The clinical scenario and relevant anatomy may affect the technique used for stoma creation and the location of the stoma. Technique Several types of intestinal stomas are recognized (see the image below). The clinical scenario often dictates the segment of intestine selected, the type of stoma created, and its external location. In children, most stomas are created as an end or loop ostomy; however, be familiar with the many potential variations in their construction. Roux-en-Y construction can also be performed for tube stomas such as feeding jejunostomy. Diagrams illustrate pediatric stomas. (A) End stoma (inset shows everting maturation); (B) double-barrel stoma: End stoma and mucous fistula are divided and brought through the same incision (inset shows closed mucus fistula sutured to abdominal wall); (C) end stoma with mucous fistula brought out separate incision; (D) end ileostomy with closed mucous fistula left inside abdominal cavity; (E) loop stoma; and (F) decompressing blowhole stoma Divided end ileostomy and ileal mucous fistula. The ileostomy is brought out through a separate skin incision. End ileostomy with closed distal limb (also known as Hartman pouch). End ileostomy with closed distal intestine after multiple resections. The segment without function is left in situ, and a stoma is used for decompression. Loop stomas provide excellent decompression and have the advantage of simple closure without the need for a separate laparotomy in most cases. However, loop stomas are not completely diverting because proximal contents can spill over into the distal limb. Therefore, they should be used with caution in patients in whom stool in the distal bowel may be problematic. A decompressing stoma, or blowhole, is created in patients in unstable condition by opening the antimesenteric border of bowel without mobilizing the entire loop of bowel. Stomas can also be formed in association with an anastomosis for proximal or distal venting or irrigation (ie, Bishop-Koop1 and Santulli stomas [see the images below). These stomas were initially designed for the treatment of infants with meconium ileus but have been adapted for many other purposes. In children with necrotizing enterocolitis, multiple intestinal atresia, or midgut volvulus in which multiple bowel anastomoses may be unsafe and in whom preservation of intestinal length is desired, one or more discontinuous segments of bowel may be externalized. The operating surgeon should clearly describe the anatomic configuration in the surgical notes and provide an illustration in the patient's chart. End-to-side anastomosis created in an infant with a complicated meconium ileus, with distal stoma used for irrigation (also known as the Bishop-Koop ileostomy). In general, a stoma is easier to manage when it is not flush with the skin. Everting the bowel prior to suturing the edge to the skin (ie, Brooke technique) produces a spigot conformation that holds a stoma appliance and prevents serositis (see the image below), inset in part A). Eversion is not always possible in neonates (in whom the blood supply may be tenuous) and in situations in which the bowel is markedly edematous. In these cases, the bowel is left to protrude through the skin without eversion, and the stoma automatically matures as the mucosa rapidly grows over the exposed serosal surface. Stoma location Intestinal stomas can be exteriorized on the neck, chest, or abdomen. The abdomen is by far the most common site for intestinal stomas. Enterostomies can be brought through the abdominal wall in the laparotomy incision or through a separate site. Theoretical disadvantages of bringing a stoma through a large laparotomy incision include the risk of wound infection, dehiscence, and evisceration. Nevertheless stomas are often incorporated into the incision, especially when the only goal of surgery is to create a stoma. Whenever clinically feasible, a primary stoma site, as well as alternative sites, should be selected and marked before surgery. The ideal location for an abdominal stoma in older children and adolescents is similar to that in adults. The stoma is distant from the incision, through the midportion of the rectus muscle away from skin folds (eg, groin, flank), bony prominences (eg, rib cage, iliac spine), and umbilicus (see the images below). Stoma location in infants and neonates follows these same principles whenever possible; however, the small size of the abdominal wall in infants and the short mesentery of the bowel chosen for the stoma often limit the options. For temporary stomas in infants, the bowel can be brought out directly through or adjacent to the umbilicus (see the images below).2 This site is easier for appliance placement and results in a cosmetically superior scar when the stoma is ultimately closed. Potential sites for neonate and infant stomas. Potential sites for stomas in an older child or adolescent. Ideally, a stoma is brought through the rectus muscle in a position that allows placement of a stoma appliance. Stoma brought directly through the umbilicus. Stoma matured through a separate inferior umbilical incision. Workup Laboratory Studies Laboratory investigations depend on the indication for a stoma. Imaging Studies 1. Imaging studies may be performed as part of the evaluation of the specific disease process and may include the following: Plain radiography Contrast enema examination (particularly before closure of stomas) CT scanning Ultrasonography 2. Prior to reversal of most ostomies in infants, consider performing a distal contrast study to evaluate the unused portion of the bowel. This is particularly important in babies treated for neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis with a diverting ostomy. Such patients may have an unrecognized distal intestinal stricture. Repair of the stricture is essential prior to, or during, the procedure for reversal of the ostomy. Diagnostic Procedures Intestinal biopsy: In selected cases in which a colostomy or ileostomy was performed for intestinal obstruction of unclear etiology, a mucosal biopsy might be helpful to rule out the possibility of Hirschsprung disease. Treatment Medical Therapy Stomas are created for the treatment of surgical diseases when no medical alternatives are available. Surgical Therapy The operation performed depends on the specific disease being treated. Injuries to the rectum and sphincter are difficult to repair in the initial setting. Minor injuries may be primarily repaired. For more extensive injuries, exploratory laparotomy should be performed to rule out intra-abdominal injuries, and a diverting colostomy should be created. Debridement of the perineum should be avoided in the initial setting. The anal sphincter can be reconstructed later. Preoperative Details Stomas are created in both elective and emergency settings. A physician, enterostomal therapist, or nurse specialist should counsel children undergoing elective colostomy as well as their families. This preparation reduces their anxiety and makes postoperative management easier. When safe to do so, the bowel is prepared mechanically and with antibiotics; however, this preparation should be avoided when an obstruction is present. The potential stoma sites should be marked preoperatively. In older children, the site should be marked with the patient in both the sitting and supine positions to ensure that the stoma appliance fits securely. The stoma site should be selected to avoid fat folds, scars, and bony prominences. A useful selection technique is drawing a vertical line through the umbilicus to the pubis and a transverse line through the inferior margin of the umbilicus. A disk the size of a stoma faceplate can then be used to determine the location. When an adequate site for all positions is found, the site should be marked with ink. After the induction of general anesthesia in the operating room, a fine needle can be used to scratch the site prior to preparation of the abdominal skin. Intraoperative Details Construction of a stoma requires the bowel to be mobile enough to be brought through the abdominal wall. Tension on the mesentery should be avoided. Ideally, stomas are brought out through separate skin incisions, but the clinical situation ultimately dictates the site used. In older children and adolescents, stomas should be brought through the rectus abdominus muscle to prevent parastomal hernias. A disk of skin is removed, and the fascia is incised longitudinally. The stoma is matured with absorbable suture after the abdominal incision is closed. In neonates and infants, the stomas may be covered with Vaseline gauze until bowel function returns. In older children, a 1-piece stoma appliance that can be cut to just fit around the stoma should be applied in the operating room. Postoperative Details Return of bowel function varies and depends on the clinical setting. Ileostomies and colostomies usually begin to function in 4-5 days. In the first few days, clear or serosanguinous fluid may appear. This finding should not be mistaken for an indication of bowel activity. An enterostomal therapist or nurse specialist should be involved early in the care of the newly formed stoma and in teaching the patient and family long-term care of the stoma. Follow-up Small bowel stomas (ie, jejunostomy, ileostomy) and proximal colostomies have liquid output. Volumes may be large, and the fluid may irritate the skin. Use of an appropriately fitting stoma bag is essential. Various stoma appliances and products are available. Stoma appliances should be able to remain in place for several days. Improperly fitted appliances leak and lead to more complications. Local irritation, skin excoriation, and yeast infections can be treated with appropriate topical medication and skin care. Mild stoma bleeding is not uncommon and usually stops spontaneously. Children with high ostomy output require close follow-up for dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Complications Stoma-related complications Many potential stoma-related complications are recognized. Skin irritation and infection are the most common complications with pediatric stomas. Excoriation from stoma effluent, candidal infection, and dermatitis are frequent; improper location or construction of the stoma and poor stoma care are often responsible. Local wound care and patient or caretaker education often corrects the problem. Occasionally, surgical revision is needed. Wound infection, wound separation, dehiscence, and postoperativesepsis may also occur after formation of a stoma, particularly if the stoma has been brought out through the wound. Stoma prolapse also is common in children. Prolapse can occur in end or loop stomas. Both proximal and distal bowel segments can protrude many centimeters (see the image below), although this complication may be more common in the distal limb. A variety of surgical techniques have been used, with mixed success, to reduce the incidence of prolapse. Once prolapse occurs, it often becomes a chronic problem that can be difficult to correct. In most cases, prolapse is an unsightly nuisance but is well tolerated by the child. Surgical revision is indicated for the rare instances of ischemia, obstruction, ulceration, or chronic bleeding. Stoma reversal is the optimal treatment. Stoma retraction results in a stoma that is flush with the skin, and difficulty in controlling the effluent may result in significant skin breakdown. Retraction of a loop colostomy results in a blowhole configuration that allows proximal contents to spill into the distal segment. Revision may be required if distal diversion is necessary. A retracted end stoma often re-protrudes spontaneously. In most cases in which the stoma is temporary, only short-term measures are needed until the stoma is reversed. Permanent stomas that have retracted may require surgical revision. Appearance of violaceous rash commonly due to Candida albicans. String coming out of the distal stoma was passed through a distal stricture and out of the anus. Skin irritation, stoma retraction, and wound infection after placement of a stoma through a laparotomy incision. Wound infection and postoperative sepsis may also occur after formation of a stoma. Note the redness of the skin at the laparotomy incision site and evidence of soft tissue abdominal wall infection. Prolapse of loop colostomy. Both proximal and distal limbs have prolapsed. This may or may not cause intestinal obstruction. Intestinal obstruction is also common. Stoma strictures can occur at the skin level, fascial level, or both. Partial obstruction can result in hyperperistalsis and hypersecretion; massive fluid losses through the stoma may result in dehydration. If a stoma stricture is suspected, the size of the opening can be determined by carefully passing metal sounds through the stoma. Attempts at dilating the stoma are usually unsuccessful and may cause intestinal perforation. Passage of a soft catheter proximal to the stricture can provide temporary decompression. Most significant stoma strictures require surgical revision; a local procedure with minimal morbidity is often possible. Parastomal hernias usually require surgical intervention. Other causes of obstruction include luminal plugging caused by ingested food, adhesive intestinal obstruction, internal hernia, and volvulus. Obstruction is usually obvious, and the diagnosis is based on the patient's history and findings at physical examination and on plain radiography. In all patients with a bowel obstruction, a nasogastric tube should be placed for decompression and the patient should receive intravenous hydration. A study with water-soluble contrast material administered through the stoma provides diagnostic information and, in most cases of luminal obstruction, is therapeutic. Most adhesive obstructions improve with nasogastric decompression and bowel rest. Prompt surgical exploration is required in patients with suspected ischemic or gangrenous bowel, clinical deterioration, or obstruction that does not rapidly resolve with nonsurgical therapy. Psychological issues can be significant for the child and the family.5 These effects can be particularly important in adolescents, who are dealing with body image and sexuality. A team approach to providing preoperative counseling, postoperative care, and rehabilitation is crucial to the wellbeing of the patient. An enterostomal therapist or nurse specialist is essential. The age of the patient and an understanding of physical and psychological changes that children with stomas experience must be carefully considered. In summary, potential stoma-related problems include the following: 1. Skin irritation - Chemical, mechanical, allergic 2. Intestinal obstruction - Adhesion, volvulus, internal hernia 3. Wound-related complications - Infection, separation, dehiscence 4. Infections 5. Prolapse 6. Retraction 7. Stricture 8. Fistula 9. Ulceration 10. Leakage 11. Bleeding 12. Parastomal hernia 13. Fluid and electrolyte imbalances 14. Psychological trauma Fluid and electrolyte problems Physiologic abnormalities related to loss of fluid and electrolytes are common in young patients with stomas, particularly when the stoma is in the proximal gastrointestinal tract. Fluid and electrolyte losses from any stoma can be significant, and replacement is usually required. The electrolyte composition of enteral fluids is listed in the following Table. Electrolyte Composition of Enteral Fluids Fluid Na+ ClK+ HCO3 - H+ mEq/L mEq/L mEq/L mEq/L mEq/L Saliva 30-60 15-40 20 15-50 N/A Gastric 60-100 90-140 10-20 N/A 30-100 Duodenal 140 80 5 50 N/A Bile 140 100 5-10 40-50 N/A Pancreatic 140 75 5-15 90 N/A Jejunal 100 100 5-10 10-20 N/A Ileal 130 110 10 30 N/A Colonic 60 40 30 20 N/A Diarrhea 130 30 90 N/A N/A Duodenal stomas are rare, but duodenal fistulas may occur after trauma or surgery. Duodenal fistulas typically have high output and, therefore, are difficult to control. Proximal jejunal stomas also tend to have high-volume output, with fluid and electrolyte losses similar to those of duodenal fistulas, except for a slightly lower sodium loss from the jejunum. Pancreatic and biliary fluids also empty into the duodenum, and secretion of these fluids may substantially increase if feeding into the stomach is initiated. Often, the proximal bowel can adapt to the fluid and electrolyte losses of a distal small bowel stoma. After a period of adaptation, the absorptive capacity of the small bowel proximal to the ileostomy increases, and the bowel can reduce ileostomy electrolyte losses by as much as two thirds of its initial output. Adaptation of water absorption is a much slower process. Ileostomy output should average 10-15 mL/kg/d. A doubling of usual stoma output should be considered abnormal. Normal ileostomy output results in the loss of 2-3 times the normal amount of salt and water, and children with these stomas are susceptible to dehydration. In infants, sodium and bicarbonate losses may exceed renal conservation mechanisms. Infants are prone to dehydration, and they may not gain appropriate amounts of weight unless salt and bicarbonate supplementation is provided. Patients with long-standing ileostomies often have hypomagnesemia and decreased absorption of vitamin B-12 and folic acid. Patients with ileostomies also have a higher incidence of renal calculi and gallstones than that of the general population. Also, they may have iron deficiency and fat malabsorption. Intestinal contents become progressively more solid as they pass through the colon to the rectum. The contents of the ileum and cecum are liquid and erosive to the skin. The contents of transverse colon stomas are typically semiliquid and less erosive, whereas those of the descending colon tend to be solid and nonreactive to the skin. These generalizations are true when the proximal bowel has sufficient length to allow absorption of nutrients and fluid. In children with short bowel syndrome, fluid and electrolyte losses can be massive, even with a distal colostomy. Outcome and Prognosis The outcome of patients with intestinal stomas depends on the underlying condition. Fortunately, most stomas in infants and children are reversible. Reestablishing bowel continuity depends on factors such as the underlying disease, the general medical condition of the child, and the presence of stoma-related complications. Understanding the anatomy prior to stoma closure is crucial. In most instances, a preoperative distal contrast-enhanced study should be performed. In general, the prognosis for patients with intestinal stomas is good. The exception is in patients with stomas and short gut syndrome. In such cases, reversal of the stoma should be attempted as soon as possible in order to maximize the absorptive capacity of the intestines. However, in many cases of short gut syndrome, ostomy reversal is not possible because of other associated comorbid conditions. The most common cause of short gut syndrome in North America is necrotizing enterocolitis. Future and Controversies In selected cases, performing ostomies using minimally invasive surgical technique (laparoscopic surgery) is possible.