DNA rotation Neck and Back Pain

advertisement

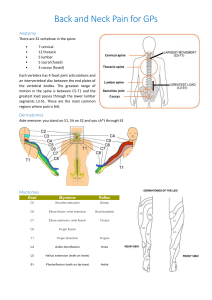

This is a good powerpoint presentation from a Family Practice website: familymedicine.moh.gov.bh/slideshows/Neck%20and%20Back%20Pain.pps Lower Back Pain Lower back pain is a very common complaint. The life time prevalence of an episode of lower back pain is 80%. Many of these episodes are relatively transient in nature and the exact cause of the pain will never be known. However, there are important causes of back pain that need to be identified. History is extremely important. There are so called “red flags” that need to be identified. Simialarly there are “yellow flags” that need to be identified. (table of red and yellow flags) Comment about the quality of the pain?? The examination of the lower back usually begins with the patient sitting in a chair. Note if the patient is sitting comfortably or whether they are in pain. Ask the patient to stand from the chair. If they require than arm rests to stand up then ask the patient to try again but this time not to use the arm rests. An inability to this is suggestive of proximal muscle weakness but can be due to severe lower back pain. Causes of back pain – can we ask for permission to use the Klippel and Dieppe table? Ask the patient to stand with their back towards the examiner. Look carefully at the back. Look for a scoliosis, loss of lumbar lordosis or kyphosis. Next palpate the spine. Initially palpate from the lower thoracic vertebrae towards the scarum. Palpate each vertebral body individually for tenderness. Palpate the sacrum then palpate the sacro-iliac joints. These are best felt below the dimples of venus. Next palpate the paraspinal muscles for tenderness and spasm. Palpate along the posterior iliac crest again for muscle tenderness and spasm. Test spinal movements. Begin with forward flexion. Ask the patient to keep their knees extended and to try and touch the ground. With hypermobility the patient will be able to place their hands flat on the ground. With disease of the lower spine there is limitation of flexion. The distance between the floor and the fingertips should be noted. Test lateral flexion. Ask the patient to slide their hand down the outside of their leg. Their fingertip should be able to reach the lower aspect of the patella. With nerve root compression the patient will have pain down the leg on the same side as the lateral flexion. Pain on the opposite side to flexion is often muscular. Test extension. Stand behind the patient and ask the patient to lean back. Ask the patient to stand straight again. Then ask the patient to rotate 45° in one direction and then lean back. Pain that is elicited in the lumbar spine is suggestive of zygophyseal joint disease. Do this again with the patient rotated in the opposite direction. A more objective measure of lumbar flexion is with the schober’s test. (diagram). With the patient standing, place a tape measure along their lumbar spine. Mark a position 10cm above the level of the dimples of venus. Firmly hold the tape measure at the distal end of the spine. Ask the patient to flex forwards with their knees extended. At maximal flexion the 10cm mark should be at least 15cm. Test quickly for muscle weakness. Ask the patient to stand of their toes. Inability to do this suggests calf weakness which could be a L5 or S1 nerve root lesion. Ask the patient to stand on their heals. Patients are often unsteady but a foot drop will be obvious. The patient must then be assessed for a specific nerve lesion. The neurological examination of the lower limb is covered else where. http://physicalexamination.org/?q=node/86 Musculoskeletal System PE http://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/Joints.html This website includes a series of pictures that are useful for joint exams; it may be overkill here though. Neurologic Exam: http://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/neuro2.htm Neck and back pain are common, particularly with aging. Low back pain affects 50% of adults > 60. Symptoms may simply be local pain, which can be sharp or dull, continuous or intermittent, depending on the cause and the degree of concomitant muscle spasms. The reflex tightening of paraspinal muscles in response to a painful vertebral column disorder may be more excruciating than the primary condition. If the spinal cord or nerve roots are affected, a variety of neurologic symptoms may result, including paresthesias and weakness. Pain may radiate distally along the distribution of affected nerve roots (radicular pain or, in the low back, sciatica). Etiology Many conditions produce neck and back pain (see Table 1: Neck and Back Pain: Causes of Neck and Back Pain ); most can involve both areas, only a few are specific to one location. Nerve compression, including herniated disk and spinal cord compression, is discussed in Spinal Cord Disorders: Spinal Cord Compression. Arthritides and ankylosing spondylitis are discussed in Joint Disorders: Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies. Nonvertebral disorders are discussed in various other chapters in The Manual. Table 1 Causes of Neck and Back Pain L O C A TI O N CONDITION N e c k o nl y Atlantoaxial subluxation Referred pain from carotid or vertebral artery dissection, angina, MI, meningitis, esophageal disease, thyroiditis Herpes zoster Temporomandibular joint disorder Torticollis L o w er b a c Lumbar spinal stenosis Osteitis condensans ilii Osteoporotic fractures (can also k o nl y be thoracic and occasionally cervical) Referred pain from hip, buttock, or pelvic disorders Referred visceral pain from aortic dissection or aneurysm, renal colic, pancreatitis, retroperitoneal tumor, pleural effusion, pyelonephritis Sacroiliac osteoarthritis Sacroiliitis Spondylolisthesis Ei th er n e c k or lo w er b a c k Ankylosing spondylitis (usually lower back and can also be thoracic) Arthritis (osteoarthritis, rheumatoid; rheumatoid rarely affects the lower back) Congenital abnormalities (eg, spina bifida, lumbar-ization of S1) Fibromyalgia Intervertebral disk disease Infection (eg, osteomyelitis, diskitis, spinal epidural abscess, infectious arthritis) Injury (eg, dislocation, subluxation, fracture) Muscle or ligament strain Paget's disease Polymyalgia rheumatica Tumor (primary or metastatic) Spinal cord compression Most often, neck or back pain derives from benign, selflimited musculoskeletal derangements, such as muscle strain, and ligament sprain. Other common causes include fibromyalgia (see Bursitis, Tendinitis, and Fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia) and osteoarthritis (see Joint Disorders: Osteoarthritis (OA)). Serious causes include infections (eg, infectious arthritis, osteomyelitis, diskitis, spinal epidural abscess), tumors (primary tumors of vertebrae or spinal cord), metastatic vertebral tumors (most often from breast, lung, or prostate), injuries (eg, fractures, dislocations, subluxations), and spinal cord compression. Causes of spinal cord compression include injuries, herniated intervertebral disks including the cauda equina syndrome, tumors, and subluxation of the first cervical vertebrae on the second (atlantoaxial subluxation). Evaluation The history and physical examination often suggest the cause of neck and back pain. Neurologic symptoms and signs are particularly important to elicit. Tests are obtained based on findings during examination. History: The nature of the pain, including location, exacerbating and relieving factors, and surrounding events, is elicited. Pain, numbness, paresthesias, or weakness along a nerve root distribution suggests nerve root compression. Weakness or loss of sensation at a spinal level, incontinence, or urinary retention may suggest spinal cord compression. Onset with injury is usually apparent, but some patients do not connect painful spasm with an apparently minor strain the previous day. Pain from injury is localized, relieved by rest, and worsened by motion. Pain from infection and malignancy is constant, unrelieved by rest, and progressive. Pain and stiffness that are worse upon awakening and last > 45 min suggest ankylosing spondylitis or RA. Pain that is diffuse or changes locations, particularly if unrelated to other factors or associated with poor sleep, suggests fibromyalgia. Morning stiffness of the spine and muscles of the proximal extremities, particularly in an older person, suggests polymyalgia rheumatica. Associated symptoms and history are important. Fever and IV drug use or known immunosuppression suggests an infectious cause. Weight loss or a history of cancer suggests a malignant etiology, either metastases or pathologic fracture. Physical examination: A general examination is performed, with particular attention to the spine, as well as careful neurologic examination. Spinal examination begins with inspection. If possible, the patient should also be observed moving (eg, walking into the office or exam room, undressing) when unaware he is being scrutinized. The neck and back are normally slightly lordotic. Contorted posture suggests muscle spasm, which can be enough to cause scoliosis. Focal erythema may indicate infection, overuse of local heat or irritant creams, or, in certain populations, use of ethnic remedies such as coining or cupping. Systematic palpation of the spinal column and adjacent areas is performed. Focal bony tenderness suggests infection, tumor, or fracture. Symmetric trigger points (areas that when palpated reproduce neck or back pain) over the back, chest, elbows, and knees suggest fibromyalgia. Trapezius trigger points may be from cervical disk disease or cervical osteoarthritis affecting the facet joints. Active and passive range of motion of the neck and back are ascertained. Decreased active range of motion often indicates pain or muscle spasm; intervertebral disk disease is a particularly common cause. Decreased passive range of motion indicates structural spinal abnormalities, most often due to osteoarthritis or multiple osteoporotic fractures, but possibly from other causes such as injuries, ankylosing spondylitis, or diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH—see Joint Disorders: Diagnosis). An electrical sensation that radiates down the spine with trunk flexion (Lhermitte's sign) suggests spinal cord compression. Complete neurologic examination is required. Signs that suggest spinal cord compression include bilateral reflex, motor, and sensory abnormalities that occur at a spinal level or that involve the anal sphincter (ie, poor rectal tone, decreased bulbocavernosus reflex or anal wink). Spinal nerve root compression may produce ipsilateral reflex, motor, or sensory deficits confined to the distribution of the affected root. In general, among reflex, motor, and sensory findings, reflex findings are the most objective, and sensory findings are the most subjective. Extra-axial joint abnormalities may suggest inflammatory arthritis, osteoarthritis, or other systemic musculoskeletal disorders that can affect the spine. Testing: If symptoms or signs suggest a serious medical condition (eg, MI, leaking or ruptured aortic aneurysm), appropriate tests should be obtained. Patients with possible spinal cord compression or spinal epidural abscess require immediate MRI; if unavailable, CT or myelography (rarely used) can be performed. For suspected osteomyelitis, imaging, usually an MRI, is performed within hours. Plain x-rays are indicated for bony injuries such as fractures, dislocations, and subluxations. Plain x-rays may demonstrate bony changes that can suggest disorders such as osteoarthritis, RA, osteoporosis, vertebral metastases, some infections, and others. However, plain x-rays also identify many abnormalities that are unrelated to symptoms. Testing for the diagnosis of most disorders in Table 1: Neck and Back Pain: Causes of Neck and Back Pain is discussed elsewhere in The Manual. A patient with a clear-cut episode of minor trauma (eg, lifting a box), no neurologic signs and symptoms, and no risk factors for pathologic fracture or subluxation may be treated symptomatically without testing. NECK PAIN The most common causes of neck pain are listed above. Patients with RA, juvenile RA, or ankylosing spondylitis may have atlantoaxial subluxation (see Neck and Back Pain: Atlantoaxial Subluxation). Causes of referred neck pain include angina, MI, arterial dissection, meningitis, esophageal obstruction, esophageal mass or inflammation, and thyroiditis. On examination, reproduction of radicular pain with neck extension and lateral rotation (Spurling's sign) suggests cervical disk disease. Signs of stroke in the presence of neck pain, particularly with pulse deficits, suggest aortic, carotid, or vertebral arterial dissection. Symptomatic treatment of musculoskeletal neck pain may require a cervical collar and contour pillow for 10 to 14 days to decrease spasm, then a cervical posture and stabilization and stretching program. BACK PAIN The most common causes of back pain are listed above. Osteoporotic fractures are a common cause of back pain in elderly women. Causes of referred pain include ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, renal colic, pleural effusion, aortic dissection, and retroperitoneal inflammation (eg, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis) or infiltration (eg, tumor). However, the etiology is often multifactorial, with an underlying condition exacerbated by fatigue, physical deconditioning, and sometimes psychosocial stress or psychiatric abnormality. Certain congenital abnormalities of the spine (eg, facet abnormalities) that were formerly thought responsible for back pain are just as common in patients without pain. Pain from osteoporotic fractures is constant but usually not progressive, may improve when supine, and usually improves over 4 to 12 wk; it can occur without a history of trauma (see Osteoporosis). Pain and stiffness in the morning in a young man suggests ankylosing spondylitis or other spondyloarthropathy. Worsening with back flexion suggests intervertebral disk disease. Worsening with extension suggests spinal stenosis, facet arthritis, or retroperitoneal inflammation or infiltration. Aggravation of lumbar and posterior thigh pain with walking suggests spinal stenosis. On examination, kyphosis (dowager's hump) suggests osteoporosis. Muscle spasm induced by straight leg raising suggests intervertebral disk disease; pain induced by straight leg raising may also suggest this but is less specific. A pulsatile abdominal mass, particularly with signs of shock, suggests ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Flank tenderness suggests pyelonephritis. Diagnostic studies may be deferred in patients with no signs or symptoms of concern if the patient is < 50, has no motor or reflex neurologic deficits, no sphincter complaints, no history of cancer, and no fever or weight loss. However, if pain persists for > 6 wk, an imaging study (if the etiology is not clear) or other diagnostic workup (directed at a specific etiology if one is clinically suspected) should be considered. The choice may depend on causes suspected. For example, if osteoporotic fracture is likely, x-ray may be adequate. Whether imaging studies should begin with plain x-rays or MRI if no specific etiology is suspected is not clear. A definitive diagnosis cannot be established in many patients. In most people with a single acute attack of low back pain, the cause is a self-limited musculoskeletal condition or is nonspecific and multifactorial, and recovery usually occurs over several days to 1 wk. In these patients, attacks may recur or symptoms may become chronic, especially if patients engage in activities beyond their physical capacities. Chronic pain (see full discussion in Pain: Chronic Pain) is a complex phenomenon often involving peripheral and central sensitization and neurologic remodeling, as well as depression and sometimes secondary gain (eg, litigation). Initial symptomatic treatment of acute nonspecific musculoskeletal back pain usually includes 1 to 2 days of rest (only if needed to minimize pain) and a subsequent lumbar stabilization program. More prolonged bed rest, traction, and corsets are generally not indicated. Exercises that strengthen abdominal and lower back muscles, along with instruction in work posture, are indicated when symptoms permit, to strengthen the supporting structures of the back and decrease the likelihood of the condition becoming chronic or recurrent. Reassurance about the benign prognosis of acute nonspecific musculoskeletal back pain can relieve anxiety. The physician should be thorough, kind, firm, and nonjudgmental. A low-dose tricyclic antidepressant may improve disturbed sleep and relieve chronic muscle pain. If depression or secondary gain persists for several months, psychological evaluation should be considered. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec04/ch041/ch041a.html Back Straight Leg Raising (L5/S1 Nerve Roots) 1. Ask the patient to lie supine on the exam table with knees straight. ++ 2. Grasp the leg near the heel and raise the leg slowly towards the ceiling. 3. Pain in an L5 or S1 distribution suggests nerve root compression or tension (radicular pain). 4. Dorsiflex the foot while maintaining the raised position of the leg. 5. Increased pain strengthens the likelihood of a nerve root problem. 6. Repeat the process with the opposite leg. 7. Increased pain on the opposite side indicates that a nerve root problem is almost certain. FABER Test (Hips/Sacroiliac Joints) FABER stands for Flexion, ABduction, and External Rotation of the hip. This test is used to distinguish hip or sacroiliac joint pathology from spine problems. [10] ++ 1. Ask the patient to lie supine on the exam table. 2. Place the foot of the effected side on the opposite knee (this flexes, abducts, and externally rotates the hip). 3. Pain in the groin area indicates a problem with the hip and not the spine. 4. Press down gently but firmly on the flexed knee and the opposite anterior superior iliac crest. 5. Pain in the sacroiliac area indicates a problem with the sacroiliac joints. http://medinfo.ufl.edu/year1/bcs/clist/extrem.html#AA32