HS Literary Criticism Primer - Baltimore County Public Schools

advertisement

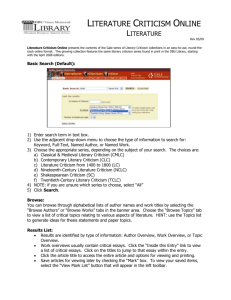

Literary Criticism: A Primer An English Office Publication By Mark Lund Carver Center for the Arts and Technology Baltimore County Public Schools Towson, MD 1996 Introduction: What is Literary Criticism? Literary criticism is the study, analysis, and evaluation of imaginative literature. Everyone who expresses an opinion about a book, a song, a play, or a movie is a critic, but not everyone's opinion is based upon thought, reflection, analysis, or consistently articulated principles. As people mature and acquire an education, their ability to analyze, their understanding of human beings, and their appreciation of artistic craftsmanship should increase. The study of literature is an essential component in this- growth of reflection. Sometimes students object to analysis and ask, "Why do we have to analyze everything? Why can't we just enjoy the books we read in English?" These are good questions, and there are some good answers for them. First, talking about an experience, actual or vicarious, is one way of increasing enjoyment. Second, sometimes talking about an experience involves recreating it in words, but it can also involve the search for meaning, in short, analysis. Finally, as Socrates said, "The life which is unexamined is not worth living." Analysis, or examination, increases awareness and understanding; it is part of the maturation process. The analysis of literature has always been part of a liberal education. When a work of literature is studied without reference to history or to the life of the author, the approach is intrinsic, or formalistic. However, literature is related to two other humanistic disciplines: philosophy and history. Philosophy explores basic, general ideas, such as truth, beauty, and goodness. History attempts to ascertain what happened in the past and why it happened. Philosophy may help readers to understand the general ideas, or themes, of a literary work. History helps to elucidate the life and times of the author. Traditionally, literary studies were conducted within the three humanistic disciplines of literature, history, and philosophy. In the twentieth century, the social sciences have been used to develop new approaches to criticism. Psychology has helped to illuminate the motivations of characters and the writers who create them. Sociology has revealed the relationships between the works the author produces and the society that consumes them. Anthropology has shown how ancient myths and rituals are alive and well in the plays, poems, and novels that are popular today. Literary criticism has been a social institution for many centuries. Different ages take different approaches, but the activity is constant. Authors are aware of criticism so that it is probably not entirely fair to say that the literary critic reads meanings into the texts that were never intended by the author. Literary criticism is not "reading between the lines" -it is reading the lines very carefully, in a disciplined and informed manner. This is why it is possible to speak of some of the approaches discussed in this booklet as elements of literature. That is, it is valid to speak of archetypal elements in a literary text, sociological elements in a literary text, and formal elements in a literary text. The approaches to literature do not put the elements there; they are already there. The approaches help to reveal and clarify them. The Formalistic Approach The formalistic approach began with Aristotle (384-322 BC), a philosopher of ancient Greece, who in his book The Poetics attempted to define the form of tragedy. Aristotle wrote that the tragic hero was an essentially noble individual who, nevertheless, manifested a flaw in character that caused him or her to fall from a high position to a low position. The flaw in character (hamartia) was a kind of blindness or lack of insight that resulted from an arrogant pride (hubris). During the course of the tragic action, the hero came to a moment of insight-today it might be seen as an epiphany-that Aristotle called anagnorsis. Thus the tragic plot moves from blindness to insight. As an imitation (mimesis) of a serious action, the tragic plot had to be written in a dignified style. The effect of the tragedy was supposed to be catharsis or the purging of the emotions of pity and fear. All the elements of tragedy went together to produce a formal unity: this is the essence of the formalistic approach. The twentieth century formalistic approach, often referred to as the New Criticism, also assumes that a work of literary art is an organic unity in which every element contributes to the total meaning of the work. This approach is as old as literary criticism itself, but it was developed in the twentieth century by John Crowe Ransom (1888-1974), Allen Tate (1899-1979), T.S. Eliot (1888- 1965), and others. The formalist critic embraces an objective theory of art and examines plot, characterization, dialogue, and style to show how these elements contribute to the theme or unity of the literary work. Moral, historical, psychological, and sociological concerns are considered extrinsic to criticism and of secondary importance to the examination of craftsmanship and form. Content and form in a work constitute a unity, and it is the task of the critic to examine and evaluate the integrity of the work. Paradox, irony, dynamic tension, and unity are the primary values of formalist criticism. Because it posits an objective theory of art, there are two axioms central to formalist criticism. One of these is The Intentional Fallacy which states that an author's intention (plan or purpose) in creating a work of literature is irrelevant in analyzing or evaluating that work of literature because the meaning and value of a literary work must reside in the text itself, independent of authorial intent. Another axiom of formalist criticism is The Affective Fallacy which states that the evaluation of a work of art cannot be based solely on its emotional effects on the audience. Instead, criticism must concentrate upon the qualities of the work itself that produce such effects. The formalistic approach stresses the close reading of the text and insists that all statements about the work be supported by references to the text. Although it has been challenged by other approaches recently, the New Criticism is the most influential form of criticism in this century. Formalism is intrinsic literary criticism because it does not require mastery of any body of knowledge besides literature. As an example of how formalistic criticism approaches literary works, consider Shakespeare's Macbeth. All the elements of the play form an organic whole. The imagery of the gradual growth of plants is contrasted with the imagery of leaping over obstacles: Macbeth is an ambitious character who cannot wait to grow gradually into the full stature of power, but, instead, must grasp everything immediately. A related series of clothing images reinforces this point: because Macbeth does not grow gradually, his clothing does not fit. At the end of the play, his "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow" soliloquy drives home the point as we see, and pity, a man trapped in the lock-step pace of gradual time. Formalistic critics would immediately see that the repetition of the word "tomorrow" and the natural iambic stress on "and" enhance the meaninglessness and frustration that the character feels. References to blood and water pervade the play, and blood comes to symbolize the guilt Macbeth feels for murdering Duncan. Even the drunken porter's speech provides more than comic relief, for his characterization of alcohol as "an equivocator" is linked to the equivocation of the witches. Shakespeare's craftsmanship has formed an aesthetic unity in which every part is connected and in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Historical and Biographical Approaches Historical criticism seeks to interpret the work of literature through understanding the times and culture in which the work was written. The historical critic is more interested in the meaning that the literary work had for its own time than in the meaning the work might have today. For example, while some critics might interpret existential themes in Shakespeare's Hamlet, a historical critic would be more interested in analyzing the play within the context of Elizabethan revenge tragedy and Renaissance humor psychology. Biographical criticism investigates the life of an author using primary texts, such as letters, diaries, and other documents, that might reveal the experiences, thoughts, and feelings that led to the creation of a literary work. For example, an investigation of Aldous Huxley's personal life reveals that Point Counterpoint is a roman a clef: the character Marc Rampion is a thinly disguised imaginative version of Huxley's friend, D.H. Lawrence. Historical criticism and biographical criticism are used in tandem to explicate literary texts. Sometimes the very premise of a novel may seem more probable if the circumstances of composition are understood. For example, students often wonder why the boys in Lord of the Flies are oil the island. Their plane has crashed, but where was it going, and why? The book may be read as a survival adventure, but such a reading would not account for the most important themes. Knowing that William Golding was a British naval commander in World War II and knowing some of the facts of the British involvement in the war help in an understanding of the novel. The most important fact relating to the premise of the novel is that during the London Blitz (1940-1941) children were evacuated from the metropolitan area: some were sent to Scotland, some to Canada and Australia. Golding imagines a similar evacuation happening during his scenario of World War III. The itinerary of the transport plane is detailed at the beginning of the novel: Gibraltar and Addis Ababa were stops on an eastward journey, probably to Australia or New Zealand. The aircraft was shot down, and the boys are stranded on a Pacific atoll. In the age of the intercontinental ballistic missile, the evacuation seems impossible, but the novel was published in 1954 when atomic weapons were still delivered principally by bombers. The history of the rise of Hitler and World War n also helps readers to understand why Ralph's democratic appeasements crumble under the ruthless aggression of Jack's regime. In short, the historical approach is vital to an understanding of literary texts. Sometimes, knowledge of history is necessary before the theme of the work can be fully grasped. The Archetypal Approach The archetypal approach to literature evolved from studies in anthropology and psychology. Archetypal critics make the reasonable assumption that human beings all over the world have basic experiences in common and have developed similar stories and symbols to express these experiences. Their assumption that myths from distant countries might help to explain a work of literature might seem a little far-fetched. However, critics of this persuasion believe it is valid. Carl Jung (1875-1961), a student of Freud, came to the conclusion that some of his patients' dreams contained images and narrative patterns not from their personal unconscious but from the collective unconscious of the human race. It was Jung who first used the term archetype to denote plots, characters, and symbols that are found in literature, folk tales and dreams throughout the world. Some of the principal archetypes are described in the following paragraphs. The Hero and the Quest According to Joseph Campbell, the story of the hero is the monomyth, or the one story at the bottom of all stories. The hero is called to adventure. This means that the hero must go on a quest. The first stage of the quest is separation: in this stage the hero separates from familiar surroundings and goes on a journey. The second stage of the quest is initiation: the hero may fight a dragon, conquer an enemy or in some other way prove his or her courage, wisdom and maturity. The final stage is the return: the hero must return to society to use the courage and wisdom gained in the initiatory phase. Often the initiation involves a journey to the underworld, and the return phase is regarded as a kind of rebirth. This links the myth of the hero to the next archetypal motif. (Mary Renault's The King Must Die (1958) is a good actualization of this pattern.) The Death and Rebirth Pattern Many myths from around the world reflect the cycle of the seasons. Sometimes mythic thought requires a sacrifice so that the seasons can continue. A sacrificial hero (in myth it is usually a god or king) accepts death or disgrace so that the community can flourish. Although the sacrifice is real, it is not necessarily to be regarded as final: the god who dies in the winter may be reborn in the spring. Characters like Oedipus and Hamlet, who sacrifice themselves to save their kingdoms, are based on the archetype of the dying god. Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" reflects this archetypal pattern in a contemporary setting. Mother Earth Father Sky A surprising number of cultures regard the earth as the mother of all life, and she is sometimes seen as the original divinity who was wedded and superseded by the archetypal male divinity, the sky god. The offspring of the earth mother and the sky father are all of the creatures that inhabit the world. Earth mother characters in literature are characterized by vitality, courage, and optimism. They represent embodiments of the life force. Shug Avery in Alice Walker's The Color Purple represents a modern version of the earth goddess: she gives Celie the courage to live. Culture Founder, Trickster, Witch Culture founders are heroes who invent rules, laws, customs, and belief systems so that society can function and people can live. Prometheus was the great culture founder of the Greeks. He created mankind and invented writing, mathematics, and technology so that human beings could survive. Because he stole fire from the gods and gave it to men, he also became a sacrificial hero, condemned to be tortured in the Caucasus Mountains until he was freed by Heracles. Modern characters who derive from the culture hero archetype would include Mr. Antrobus in The Skin of Our Teeth and Finny in A Separate Peace. Both of these characters are creative inventors, organizers, and leaders. The antithesis of the culture hero is the trickster. Representing the forces of chaos, the trickster delights in mischief. At times the trickster may appear evil, but the essential quality embodied by this archetype is childishness. Hermes is the trickster in Greek myth; Loki, in Norse myth. Native American myths have many trickster figures. In William Golding's Lord of the Flies Ralph's culture-founding efforts are constantly subverted by Jack, a trickster figure who is motivated only by the idea of fun. The female trickster contrasts with the earth goddess figure in that she devotes herself to pleasure rather than nurturing: she is referred to as the outlaw female or witch. Medea comes close to epitomizing this archetype. Four Elements = The World Earth, water, fire, air: these are the symbolic elements that compose the world. Earth usually has the connotations of nurturing life. Water may purify, and flowing rivers represent the flow of life; but water may also destroy when it is uncontrolled, as in a flood. Fire represents destruction, but it can also purify and make way for the new. Air is the spiritual element; words denoting the spirit are often derived from the words for wind. The other term for archetypal criticism is myth criticism. Literary critics, poets, and storytellers all use myths in the creation and interpretation of literature. This reflects their belief that the old myths, far from being falsehoods, reveal eternal truths about human nature. Deconstruction Most people would identify the current era of literature as the modern period; surprisingly, literary critics and historians do not. Contemporary literature (1945 to the present) is called Postmodernist. Modernism as a literary term is applied to the writers of the first half of the twentieth century who experimented with forms of writing that broke age-old traditions: writers like T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Langston Hughes, and William Faulkner. These writers viewed human beings as trapped in tragic paradoxes that could only be expressed by difficult and unorthodox styles. The writings of the modernists are regarded as classics of the twentieth century, but contemporary writing has moved beyond them. The tragic stance has given way to irony, and the break up of the culture is treated with sardonic humor. Since 1945 everything is disposable: books, culture, social mores, even-with nuclear weapons- planet Earth itself. Television, with its thousands of stories and its parodies of literary classics, cuts against the privileging of any story as a work of art. In the Postmodern Age, there is no literature, there are only stories; there is no wisdom, there is only information, and information is, almost by definition, disposable. Tom Stoppard's play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead illustrates some of the principal qualities of Postmodern literature. Aristotle's notion of the noble hero is undercut by two bumbling antiheroes who don't have enough individual identity to be able to tell themselves apart. They intrude from the margins of Shakespeare's Hamlet, wander and wonder aimlessly, and are finally packed off to a meaningless execution, disposable tools in a nasty internecine conflict. Shakespeare's play has form and purpose; the hero has a role to play in life, even though he may have doubted this at the beginning of the play. Stoppard's heroes make jokes about death, about fate, about everything. Stoppard's plot doesn't really go anywhere because like Pirandello's six characters and Beckett's two tramps, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are characters in search of a plot. Worse, they are characters in search of personalities. In the film version, pages of dramatic scripts float and swirl about all the scenes like autumn leaves or trash escaped from the recycling bin. The tragic world of Hamlet is subverted by the ironic Postmodern interlopers, proving that even a mighty Shakespearean text can be deconstructed, that is, reduced to meaninglessness. Deconstruction is the movement in criticism that best expresses the Postmodern consciousness. It has supplanted New Criticism in most of the literature departments of American colleges and universities. Deconstruction might be regarded as the antithesis of formalism. Where the formalist critic seeks to demonstrate the organic unity of a literary work, the deconstructionist tries to show how attempts at unified meaning are doomed to failure by the nature of language itself. Thus, to deconstruct a literary work is to show that it is self-contradictory. Originating in a radical skepticism about the capacity of language to mean anything, deconstruction thrives on the paradoxes of twentieth century thought. As Freudian psychology destroyed the notion that the conscious self controls the person, as Einsteinian physics undermined ideas of objectivity, deconstruction assaults the belief that language is unequivocal in its meaning and that literary works have a stable meaning intended by the author. Formalist critics accepted the intentional fallacy because they thought that the literary text could stand on its own without reference to authorial intention, but for the deconstructionist literary texts crumble into contradictions under analysis. Before deconstruction became a trend in criticism, even before the word deconstruction entered the language, Lawrence Durrell (1912-1990), wrote what might be regarded as the classic deconstructive narrative, The Alexandria Quartet. Completed in 1960 and composed of four novels that relate the same events from different points of view, the Quartet does not attempt to establish one version of the story as definitive. Rather, in a relativistic universe perspective rules the world: one step to the left or right and the whole picture changes. Feminist Criticism During the 1960s a new school of criticism arose from the struggles for women's rights. While social and economic justice were the most obvious goals of the feminist cause, many women realized that the roots of the inequality were cultural. This perception led to the development of feminist literary criticism. Using psychological, archetypal, and sociological approaches, feminist criticism examines images of women and concepts of the feminine in myth and literature. Feminist critics have shown that literature reflects a patriarchal, or male dominated, perspective of society. Patriarchalism is an ideology that causes women to be depicted in two ways: as goddesses when they serve the patriarchal society in the role of virtuous wives and mothers as prostitutes and witches when they do not. Plays and novels often reveal both views of women. Thornton Wilder parodies these stereotypes with the characters of Mrs. Antrobus and Lily Sabina in the play The Skin of Our Teeth. Wilder does not spare the patriarchal Mr. Antrobus, whose foibles are plain for all the audience to see. A fresh approach to the investigation of literature, feminist criticism often focuses on characters and issues that have been neglected or marginalized in previous studies. So much has been written about Prince Hamlet, that feminist interpretations of the motivations and conflicts of Queen Gertrude and Ophelia are often striking in their originality. Similarly, Charlotte GilmanPerkins "The Yellow Wallpaper" brings feminist criticism to the foreground. It is this freshness of approach that makes feminist criticism one of the most exciting contemporary approaches to literature. As a form of sociological criticism, feminist criticism shares some qualities with Marxist approaches. Both are critical of society, as it is presently constituted. Both are concerned with the lives of those oppressed or marginalized by the dominant culture. Both investigate literature as a means of bringing about changes in attitudes and ultimately in society. The Philosophical Approach The philosophical (or moral) approach to literature evaluates the ethical content of literary works and concerns itself less with formal characteristics. Philosophical criticism always assumes the seriousness of literary works as statements of values and criticisms of life, and the philosophical critic judges works on the basis of his or her articulated philosophy of life. Assuming that literature can have a good effect on human beings by increasing their compassion and moral sensitivity, this form of criticism acknowledges that books can have negative effects on people as well. For this reason, philosophical critics will sometimes attack authors for degenerate, decadent, or unethical writings. While this description may make philosophical critics seem similar to censors, these critics rarely call for burning or banning of books. Unlike censors, they try to deal with the whole literary work rather than with passages taken out of context. Some people might criticize J .D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye because Holden Caulfield is a poor role model. The book might also be attacked because of its profane language. In fact, these aspects of the novel have led to its being banned in many school districts throughout the United States. Although the philosophical critic may find both of these aspects of the novel disturbing, he or she might still believe that, on balance, the book was to be commended for its indictment of hypocrisy and materialism. For the philosophical critic, it is not a question of objectionable characters and passages; it is a question of the totality of the work. Instead of banning books that they find to be without redeeming social merit, philosophical critics write scathing reviews explaining why they consider the books they are attacking to be decadent or unethical. In the twentieth century, philosophical critics have tended toward a humanistic belief in reason, order, and restraint. This explains their reluctance to ban books despite their moral concerns: if human beings are rational, as the philosophical critic believes, they will listen to reason when it is spoken; and they will reject evil and embrace the good. The Psychological Approach The psychological approach has been one of the most productive forms of literary inquiry in the twentieth century. Developed in the late 1800s and early 1900s by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and his followers, psychological criticism has led to new ideas about the nature of the creative process, the mind of the artist, and the motivations of characters. Freud's principal ideas are essential to an understanding of modern literature and criticism. Although the works of Freud consist of many complex volumes, there are four main ideas that have been so influential that it is hard to believe they were not always with us. The Unconscious According to Freud, human beings are not conscious of all their feelings, urges, and desires because most of mental life is unconscious. Freud compared the mind to an iceberg: only a small portion is visible; the rest is below the waves of the sea. Thus, the mind consists of a small conscious portion and a vast unconscious portion. Repression Observing the conservative, prudish upper middle classes of the late nineteenth century, Freud came to the conclusion that society demands restraint, order, and respectability and that individuals are forced to repress (or sublimate) the libidinous and aggressive drives. These repressed desires, however, emerge in dreams and in art. The artist and the dreamer are both creators; both have a need to express themselves by creating beautiful or terrifying images and narratives. But the lust and aggression may not be represented directly. This leads to the use of symbols and subtexts in dreams and literature. The Tripartite Psyche Freud developed his psychoanalytic theory around three principles: the ego, the id, and the superego. The ego is conscious and represents the part of the mind that interacts with the environment and with other people in social situations. As the conscious waking self, the ego is the reasonable, sane, and mature aspect of the mind capable of mastering impulses and dealing effectively with the stresses of daily life. Common parlance may show disrespect for the "big ego," but for Freud the supercilious attitude denoted by this phrase would, paradoxically, be an indication - of a weak ego. The id is unconscious and is comprised of the basic drives of hunger, thirst, pleasure, and aggression. The id is removed from reality, that is, from the outer world of society and environment. The id is the mind of the infant, demanding instant gratification, incapable of tolerating the delayed gratification that makes the ego socially acceptable. At first, Freud thought that the id had only one principle, the pleasure principle, also known as the libido or sex drive. However, he found he could not account for aggression, violence, and selfdestructiveness without postulating a second principle, the aggressive drive, also known as the death wish. The superego is the final part of the tripartite psyche. Representing parentally instilled moral attitudes, the superego may seem to be like the conscience. Like the id, however, the superego is largely unconscious. Sometimes the superego is thought to represent an idealized image (ego-ideal) towards which the ego strives. During the normal course of development, an individual gains in ego strength and is able to master basic drives and mediate the demands of the id, the superego, and the environment. Many works of literature contain characters who embody mental forces. Some of these works were written long before Freud formalized his psychological theory. Three famous works of Victorian literature were published at about the time Freud was developing his ideas: Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), and Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Sharer" (1912). Probably the most notorious id character ever created, Mr. Hyde incarnates the aggressive drive of the unconscious; however, Dr. Jekyll makes it clear in his statement of the case that he admired Hyde's tremendous love of life. In a similar way, the captain in Conrad's story recognizes that Leggatt has killed a man, but he allows Leggatt to swim to a nearby island because he admires the freedom and self-possession of Leggatt. Both Dr. Jekyll and the captain live in L-shaped dwellings: like Freud's iceberg, part of the dwelling is seen and part remains hidden. Wilde's Dorian Gray resorts to hiding his portrait (which shows his moral state) in the attic. In each of these works, an ego character must mediate between the social environment and the desires of the id character. The id is not so much immoral as amoral. It is the way in which the ego character deals with the drives of the id that constitutes the moral action of the story. The Oedipus Complex In Greek myth, Oedipus was a king of Thebes who, having been abandoned in childhood and consequently ignorant of his own identity, unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. In describing the psychosexual development of children, Freud analyzed the powerful feelings that develop between mother and son. Freud believed that boys develop strong attractions to their mothers during the phallic period (3-6), with a corresponding rivalry developing between the boy and his father. Usually these conflicts are resolved as the boy matures and develops love interests outside the home, but some neuroses of adult life are supposed to result from insufficiently resolved Oedipal conflicts. The Oedipus Complex has been very controversial and some psychoanalysts have modified or rejected it. Alfred Adler (1870-1937), one of Freud's pupils, reinterpreted the Oedipus Complex when he developed his own theory of the Inferiority Complex. Adler believed that the primary motivation for human beings is not the libido, as Freud had posited, but the will to power. For Adler, then, the Oedipus Complex is essentially a power struggle between the boy and the father, in which the boy tries to overcome feelings of inferiority by successfully capturing the mother's attention. Adler also coined the term masculine protest to refer to the rebellion of by young women (and some young men) against the inferior status that women have in many societies. Masculine protest consists of aggressive behavior towards others in an attempt to allay feelings of inferiority. Writers were interested in the powerful conflicts that arise in families long before Freud, but writers of the twentieth century exploring these conflicts in their works will be labeled Freudian whether they acknowledge the influence of Freud or not. D.H. Lawrence's Sons and Lovers explores the influence of a possessive mother on her sons; the same author's story " The Rocking- Horse Winner" depicts a boy who believes he can win his mother's love by being lucky in gambling on racehorses. Frank O'Connor's "My Oedipus Complex" is a humorous treatment of Freud's ideas. The same author's "Masculine Protest" makes use of the Adlerian notion of the inferiority complex. The literature of the past has been reexamined in the light of psychoanalysis. Freud himself started this trend when he named a complex after Oedipus: this reinterpreted the play. In fact, the play was profoundly psychological in its original conception. Oedipus goes to Delphi and receives, prophecies from the gods: what better way to express the working of the unconscious? Jocasta tells Oedipus that many men have dreamed of sleeping with their mothers: dreams do reveal unconscious desires. Finally, having sorted out his identity, Oedipus, analyst and patient in one paradoxical person, blinds himself and leaves the stage to wander the world, a sadder and a wiser man. Since the late 1940s Shakespeare's Hamlet has been interpreted as having an Oedipal Complex. He expresses love for his mother, and seems obsessed by the idea of Claudius and Gertrude sleeping together. His jealousy and aggression towards Claudius are overt. Of course, c Claudius is not Hamlet's father but his stepfather. Hamlet idealizes and adores his real father. These facts do not deter the psychological interpreters. Perhaps the concept of masculine protest is as, applicable to the playas the Oedipal conflict. Hamlet feels that Gertrude is weak; worse, he feels implicated in her weakness. Much of the play dwells on Hamlet's feelings of weakness and inferiority, and his aggressive behavior at the end may be interpreted as masculine protest. Poets, dreamers, and madmen all tap the fountainhead of the unconscious, the source not only of aggressions and desires but of the will to live. The psychological approach to literature delves into the symbolic fictions that arise from the primordial springs of the imagination and attempts to explain them to the rational, waking selves who inhabit the daylight world. The Sociological Approach Sociological criticism focuses on the relationship between literature and society. Literature is always produced in a social context. Writers may affirm or criticize the values of the society in which they live, but they write for an audience and that audience is society. Through the ages the writer has performed the functions of priest, prophet and entertainer: all of these are important social roles. The social function of literature is the domain of the sociological critic. Even works of literature that do not deal overtly with social issues may have social issues as subtexts. The sociological critic is interested not only in the stated themes of literature, but also in the latent themes. Like the historical critic, the sociological critic attempts to understand the writer's environment as an important element in the writer's work. Like the moral critic, the sociological critic usually has certain values by which he or she judges literary work. Marxist Criticism One of the most important forms of sociological criticism is Marxist criticism. Karl Marx (1818-1883) developed a theory of society, politics, and economics called dialectical materialism. Writing in the nineteenth century, Marx criticized the exploitation of the working classes, or proletariat, by the capitalist classes who owned the mines, factories, and other resources of national economies. Marx believed that history was the story of class struggles and that the goal of history was a classless society in which all people would share the wealth equally. This classless society could only come about as a result of a revolution that would overthrow the capitalist domination of the economy. Central to Marx's understanding of society is the concept of ideology. As an economic determinist, Marx thought that the system of production was the most basic fact in social life. Workers created the value of manufactured goods, but owners of the factories reaped most of the economic rewards. In order to justify and rationalize this inequity, a system of understandings or ideology was created, for the most part unconsciously. Capitalists justified their taking the lion's share of the rewards by presenting themselves as better people, more intelligent, more refined, more ethical that the workers. Since literature is consumed, for the most part, by the middle classes, it tends to support capitalist ideology, at least in countries where that ideology is dominant. Marxist critics interpret literature in terms of ideology. Writers who sympathize with the working classes and their struggle are regarded favorably. Writers who support the ideology of the dominant classes are condemned. Naturally, critics of the Marxist school differ in breadth and sympathy the way other critics do. As a result, some Marxist interpretations are more subtle than others. Take the Marxist approach to Shakespeare's The Tempest for example. The standard Marxist party line would be to interpret Prospero as the representative of European imperialism. Prospero has come to the island from Italy. He has used his magic (perhaps a symbol of technology) to enslave Caliban, a native of the island. Caliban resents being the servant of Prospero and attempts to rebel against his authority. Since Prospero is presented in a favorable light, the Marxist critic might condemn Shakespeare as being a supporter of European capitalist ideology. A more subtle Marxist critic might see that the play has far more complexity, and that Caliban has been invested with a vitality that makes it possible for audiences to sympathize with him. Certainly, the Marxist view of the play brings out ideas that might be overlooked by other kinds of critics and, thus, contributes to the understanding of the play. Sociological criticism, then, reflects the way literature interacts with society. Sociological critics show us how literature can function as a mirror to reflect social realities and as a lamp to inspire social ideals. Glossary abstruse: Adlerian: difficult to understand; abstract of, or relating to, the pschological theories of Alfred Adler ( 1870 -1937) stressing the will to power as the primary human motivation aesthetics: the philosophical study of beauty and the arts amoral: without a sense of morality anagnorisis: the moment of revelation at the end of a tragedy antithesis: polar opposite artifact: an object made by human beings for an intended use criterion: a standard or guideline for evaluation deconstruction: a literary approach that seeks to undermine the notion that a literary text has a fixed meaning ego: the Freudian term for the conscious, waking self epiphany: a sudden moment of clarity or recognition existentialism: philosophy stressing the radical freedom of the individual; according to this philosophy human life has no meaning except that created by individuals expressive theory: the idea that a work of art emanates from the experience and imagination of the artist extrinsic: exterior; approaches to criticism that depend upon non-literary criteria Freudian: of, or pertaining to, the psychological theories of Sigmund Freud (18561939) stressing the libido as the primary human motivation hamartia: a flaw in character resulting in moral blindness hubris: arrogant pride which leads to a fall id: the aspect of the unconscious mind that encompasses the libido and aggressive drive ideology: intrinsic system of understandings which may be conscious or unconscious inferiority complex: lack of self -esteem deriving from feelings of powerlessness integrity: wholeness; the parts of a literary work are assumed by New Critics to constitute a meaningful whole intentional fallacy: the theory that an author's purpose in creating a work is irrelevant to the interpretation of the work intrinsic: interior; the formalist approach to criticism emphasizes purely literary criteria irony: a technique in which the expected is subverted by the unexpected libido: Freudian term for the pleasure principle or sexual drive mimetic theory: the idea that a work of art imitates life modernism: literary movement of the first half of the twentieth century characterized by experimentalism and anxiety New Criticism: a twentieth century formalistic approach emphasizing organicism, irony, and tension objective theory: the idea that a work of art is to be analyzed by intrinsic criteria Oedipus Complex: the Freudian idea that young boys have libidinous feelings for their mothers with corresponding feelings of guilt and aggression for their fathers organicism: pathetic fallacy: postmodernism: pragmatic theory: roman a clef: superego: the New Critical idea of the work of art as a unity that transcends the sum of its parts the New Critical rejection of effect on the audience as a criterion for evaluation the literary period since 1950 characterized by decentralization, skepticism and parody the idea that the rhetorical effect of a work on the audience is the central criterion for evaluation [Fr. novel with a key] a novel in which the characters are based on real people whose names have been changed aspect of psyche that incorporates parentally-instilled morals Works Cited Guerin, Wilfred L.,et al. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature. 3rd. ed. New York: Oxford UP, 1992. Lynn, Steven. Texts and Contexts. New York: Harper Collins, 1994. Meyer, Michael, ed. The Bedford Introduction to Literature. New York: St. Martins, 1994.