Bar Graph - Rules/Exam

advertisement

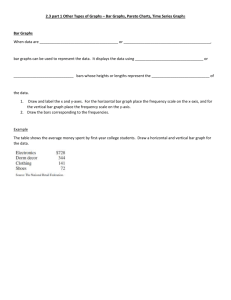

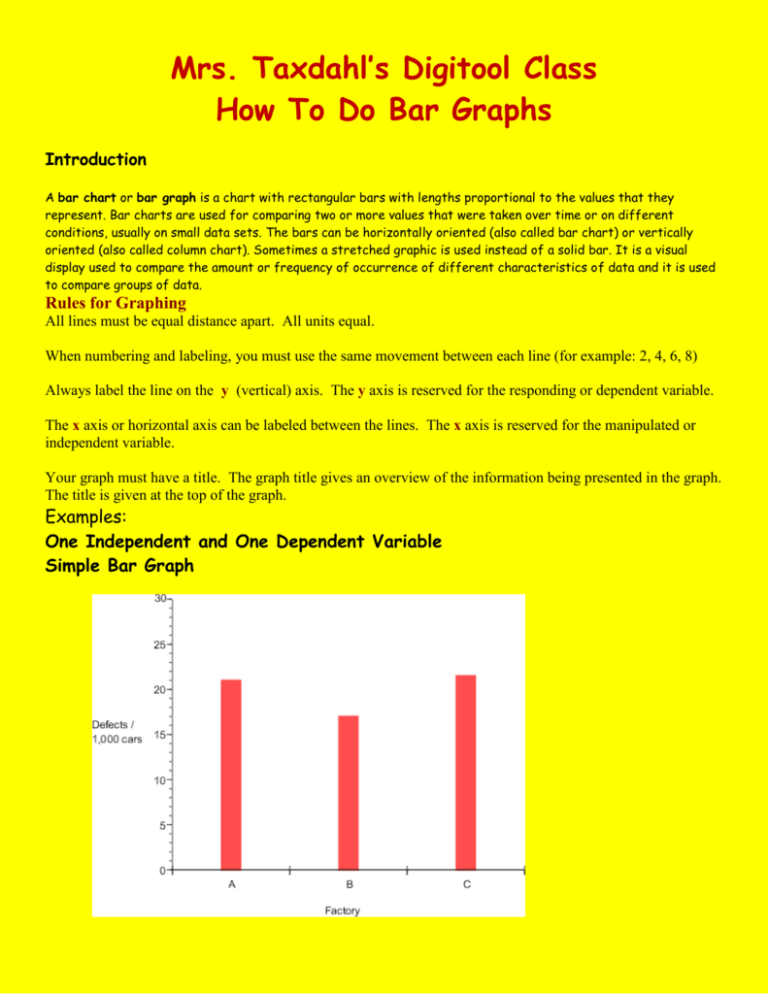

Mrs. Taxdahl’s Digitool Class How To Do Bar Graphs Introduction A bar chart or bar graph is a chart with rectangular bars with lengths proportional to the values that they represent. Bar charts are used for comparing two or more values that were taken over time or on different conditions, usually on small data sets. The bars can be horizontally oriented (also called bar chart) or vertically oriented (also called column chart). Sometimes a stretched graphic is used instead of a solid bar. It is a visual display used to compare the amount or frequency of occurrence of different characteristics of data and it is used to compare groups of data. Rules for Graphing All lines must be equal distance apart. All units equal. When numbering and labeling, you must use the same movement between each line (for example: 2, 4, 6, 8) Always label the line on the y (vertical) axis. The y axis is reserved for the responding or dependent variable. The x axis or horizontal axis can be labeled between the lines. The x axis is reserved for the manipulated or independent variable. Your graph must have a title. The graph title gives an overview of the information being presented in the graph. The title is given at the top of the graph. Examples: One Independent and One Dependent Variable Simple Bar Graph The above "Factory" is our independent or manipulated variable, since there is no unit of measurement for factories and no 'order' to the factories, the independent variable is nominal. The dependent or responding variable is scalar, measured in defects/1,000 cars. Since the scalar dependent variable has a natural zero point (i.e., absolute or ratio), all of the bars are anchored to the horizontal axis, giving a common point of measurement. 1. Horizontal Bar Graph Bar graphs can be shown with the responding or dependent variable on the horizontal scale. This type of bar graph is typically referred to as a horizontal bar graph. Otherwise the layout is similar to the vertical bar graph. Note in the example above, that when you have well-defined zero point (ratio and absolute values) and both positive and negative values, you can place your vertical (manipulated or independent variable) axis at the zero value of the responding or dependent variable scale. The negative and positive bars are clearly differentiated from each other both in terms of the direction they point and their color. 1. Range Bar Graph Range bar graphs represents the responding or dependent variable as interval data. The bars rather than starting at a common zero point, begin at first dependent variable value for that particular bar. Just as with simple bar graphs, range bar graphs can be either horizontal or vertical. Notice in the horizontal example above, a reference line is used to indicate a common key dependent variable value. 1. Histogram Histograms are similar to simple bar graphs except that each bar represents a range of independent variable values rather than just a single value. What makes this different from a regular bar graph is that each bar represents a summary of data rather than an independent value. For this type of graph, the dependent variable is almost always a scalar scale representing the count, or number, of how many of a sample fall within each range of the independent variable. In the example above, the sample is all the females in the U.S. The independent variable is age, which has been grouped into ranges of 5 years each. You should try and keep the ranges for each bar uniform (5 years in this case), with the exception possibly being the first and/or last range. Two (or more) Independent and One Dependent Variable 1. Grouped bar graph The grouped bar graph is the same graph as seen above but we added a second independent variable, year. The initial independent variable, factory, is nominal. The second independent variable, year, can be treated as being either as ordinal or scalar. This is often the case with larger units of time, such as weeks, months, and years. Since we have a second independent variable, some sort of coding is needed to indicate which level (year) each bar is. Though we could label each bar with text indicating the year, it is more efficient to use color. We will need a legend to explain the color coding scheme. Note that all of the bars for each level of factory are touching each other, indicating visually that they are grouped together. 1. Composite bar graph Another alternative for a bar graph with two independent variables is to have the bars stacked rather than side-by-side. This arrangement is useful when the summation of all the levels of the second independent variable is as or more important than the values for each level. In the upper example, it is very easy to read the summed weight of all of the different materials in each sample. There are, however, tradeoffs. The stacking of the bars means there is no common baseline for the individual bar elements, making it hard to make direct comparisons for the subcategories. For example, it is hard to compare the iron content of the three samples. A particularly powerful use for the composite bar graph is when the sum of all the dependent variable values for each bar is the same, such as when the values are a fraction of a whole. In the bottom example, the sum of the three different types of fats will always equal 100 percent. With this layout it is easier to see the relative portions, if not the absolute values, of a particular fat type across oils. Specific tips for bar graphs on Excel: Vertical bar graphs are called column graphs in Excel Horizontal bar graphs are called bar graphs in Excel The clustered sub-type will do single bar and grouped bar graphs The stacked subtype will do composite bar graphs Range bars cannot easily be done in Excel without additional custom graph types loaded Double-clicking on the bars will allow you to set your preferences for bar display. Under the Options tab you can set the ratio of the bar width to gap between bars