Ron Moore had possession of evidence that would have cleared the

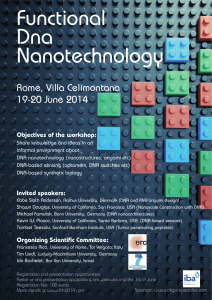

advertisement