Dogs Keep Their Genes on a Short Leash

Dogs Keep Their Genes on a Short

Leash

By

Michael Price

10 August 2010

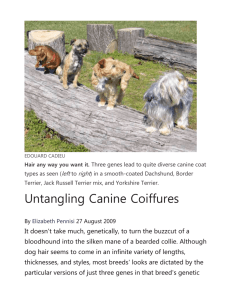

Great Danes stretch more than a meter from paw to shoulder and can easily weigh more than 90 kilograms. A Chihuahua fits snugly inside a purse. Domestic dog breeds are more varied in body size and shape—not to mention coat color and fur length—than any other land-based mammal. Yet, according to a new study, a mere two to six regions in doggy DNA account for most of this diversity.

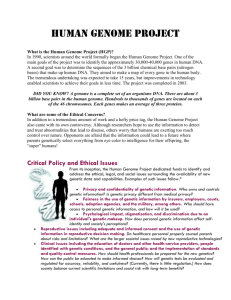

Over the past few years, researchers have linked a number of canine traits—from size to coiffure — to specific mutations in dog DNA. This new line of research was made possible by the completion of the Dog Genome Project in 2005 by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) in

Bethesda, Maryland. But researchers lacked a large-scale analysis of these traits across a wide variety of breeds. As a result, they didn't know whether traits were governed by a large number of genetic regions, each contributing a small effect, or by a few regions with large effects.

So a team led by Carlos Bustamante, a comparative geneticist at Stanford University in Palo Alto,

California, and Elaine Ostrander, a comparative geneticist with NHGRI, analyzed genetic information from 915 domestic dogs representing 80 different breeds. The researchers compared the dogs' DNA, looking for sequences that differed by a single base, known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Once they found out where the DNA differed, they compared those differences between dogs with, for example, short versus long legs or perky versus droopy ears.

All told, the researchers identified 51 regions in the genome that contributed to physical variation among the breeds. These regions can be clumped into larger areas of the genome called quantitative trait loci, which are known to contain genes that produce a specific physical effect, such as shaggy hair. Depending on which traits are compared, genetic differences in two to six of these regions—which include genes, many of which haven't yet been mapped to specific traits—can account for about 80% of the variation in physical characteristics among dogs, says Bustamante.

That differs significantly from humans, he says, whose physical variation is scattered far more widely across their genome, often comprising hundreds or thousands of regions.

Why the difference? The most likely culprit is selective pressure caused by human-directed breeding, the researchers conclude. Co-author Heidi Parker, a geneticist at NHGRI, says that because humans initially bred dogs for specific traits—say, smaller body size or calm temperament—selection created a population "bottleneck" that narrowed the genetic variation in offspring, leaving them with just a few specific clusters of variable genetic regions. Variable genes within these clusters, such as those that govern snout length or leg length, were then selected for by humans to create the dog breeds we recognize today. The appearances shifted dramatically while the overall genetic architecture remained largely unchanged. "There's no reason to come up with a new way to be short when you already have one that works perfectly fine," she says.

Bustamante says the research— reported online today in PLoS Biology—could be important to human health, because dogs and humans are so closely tied. "Dogs live with us and experience the same environments we do, and so they are exposed to the same things that we are."

The study validates the idea that a relatively small amount of genetic variance can lead to a large degree of physical diversity, says Jeffrey Phillips, a veterinary geneticist at the University of

Tennessee, Knoxville. The findings corroborate what many in the field suspected but do so with "a very, very impressive sample size," he says. "It's a wealth of information."