Horror Heritage

advertisement

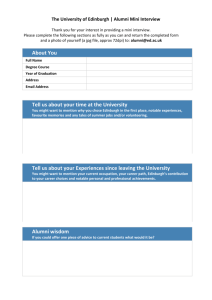

An Investigation into Edinburgh's Horror Heritage Introduction to Case The focus of this case is to analyse and critically investigate Edinburgh's horror heritage tourism industry, how it has been packaged and sold to willing consumers, and the implications associated with this. The study will attempt to give a balanced view of Edinburgh's horror heritage attractions and their importance as cultural tourist destinations, empirically locating the investigation through a case study approach of four key attractions: the Edinburgh Dungeons, Mercat Tours, The Real Mary King's Close, and the Horrible Histories Bus Tour. The study will then go on to highlight the key issues associated with the market, such as the importance of both the experience economy (Pine and Gilmore, 1999) and the Dream Society (Jensen, 1999), and the problems surrounding authenticity of attractions, and the commercialisation of culture. Section 1 - Background Information The four main attractions on which this study will focus are as follows: The Edinburgh Dungeon The Edinburgh Dungeon is currently owned by Merlin Entertainments Group. Based on the popular London Dungeon, it was built at a cost of £5 million (Editors of the Gazetteer for Scotland, 2010). At present, the attraction boasts 11 actor led shows and two rides, with attractions including characters from Edinburgh and Scotland's colourful and often gruesome history, such as Sawney Bean, William Wallace, and (new for 2010) Burke and Hare. (Edinburgh Dungeon, 2010) “Edinburgh Dungeon’s eclectic mix of fact and fantasy, education and entertainment, ensures that ticket holders on a family day out are guaranteed a thrilling and captivating family day out...the educational aspects of Edinburgh Dungeon make a trip to it both memorable and exciting” (British Attractions, 2010). Mercat Tours Mercat Tours was founded in 1985 and currently Employs 10 permanent staff, drawing on a team of 50 self-employed guides and 15 on-street sales staff. They provide 13 tours daily in the high season, 8 in the low season, and they operate all year round except 4th, 24th, 25th and 26th December and Hogmanay evening. Their tours include five ghost tours and two historic tours, which take audiences on a journey through Edinburgh's dark past. Their mantra is “History is a damn good story. What it needs is a damn good telling.” (Mercat Tours, 2010) The Real Mary King's Close Opened in 2003 as a tourist attraction, with guided tours throughout the day year-round. The costumed guides play five historic characters, leading visitors through the underground alley and into rooms that haven't changed in 250 years. Using first-person narration, they describe 16th Century tenement life, the plague epidemic of 1645, and the ghosts that are said to occupy the premises today. (One such ghost, a little girl named Annie, attracts gifts of dolls and money that ultimately get donated to a children's charity.) (The Real Mary King's Close, 2010). Horrible Histories Bus Tour As part of City Sightseeing's open-top bus tours, the Horrible Histories Tour of Edinburgh was launched in 2007, written and recorded by Terry Deary – author of the best selling books. It gives gory details of Edinburgh's truly terrible past and has proved popular with school groups and families. (City Sightseeing, 2010) Section 2 – Critical Analysis of Edinburgh's Horror Heritage According to Pine and Gilmore (1999) consumers are no longer interested in mere tangible goods; they seek the intangible products of memories and experience. Miles and Miles (2004) highlight a key function of industrialised tourism is to package and sell fantasies and it is how the tourism industry does this that invariably demonstrates the notion that Pine and Gilmore's 'experience economy' is rife, particularly in relation to Edinburgh's horror heritage. There are four realms under which a participant can consume an experience: entertainment, educational, esthetic and escapist (Pine and Gilmore, 1999). Though each realm has its varying levels of immersion and participation, Pine and Gilmore argue that through blurring the boundaries between each, consumers will receive the most rounded and memorable experience. In terms of Edinburgh's various sites of horror heritage, it seems that this blurring is evident; for 'scare' attractions such as Mercat Tours, the Edinburgh Dungeon and The Real Mary King's Close, organisers have incorporated a story to captivate its audience (entertainment) meshed with historical fact (educational), a scene in which they can actively participate - for example a mirrored maze in the Dungeon - (escapist), and theming and actors to set the scene (esthetic). Some of Edinburgh's key horror heritage sites rely heavily on extensive theming, though others effectively utilise the existing surrounds, and Bryman (2004) indicates the importance of theming in asserting a place's sense of meaning and symbolism. In the case of the Edinburgh Dungeon, its various in-house attractions rely on settings and surroundings over-exaggerated with gore; blood splattered walls, fake corpses littering the corridors. In the Dungeon, theming is essential in order to assert it as a site of horror, and without it the overall impact, and therefore overall experience, could be in jeopardy. Pine and Gilmore (1999) allude to the importance of theme as part of immersion, without such 'positive cues', full immersion into the experience cannot be assured. However, it can be argued that good theming alone is not enough to ensure immersion. The post-tourist is well aware that what they see before them is not real – they are aware of the animatronics, the fibre-optics, and the actors (Urry, 2002). Drawing on Jensen's (1999) work on the Dream Society, it can be argued that in order for something fake to become “an improvement on reality” (Pine and Gilmore, 1999:37) it takes more than mere trickery of the five senses – it takes the construction of a story. Jensen (1999) believes that we have entered a new era beyond the information society, where a products story overrides its function in terms of importance. These stories can be constructed through fact, but it is also common for some stories to be based upon myth. Rojek and Urry (1997) have stated that “mention of the mythical is unavoidable in discussions of travel and tourism. Without doubt the social construction of sights always, to some degree, involves the mobilisation of myth.” (1997:53). Utilising Rojek and Urry's theory to critically analyse Edinburgh's horror heritage, we can see there is truth to this statement. The Dungeon houses eight attractions, four of which are unique to Edinburgh, based around famous stories and villains. Burke and Hare are featured, as is William Wallace, 'Mary King's Ghost' (based around the infamous tales of the supernatural regarding Mary King's Close), and Sawney Bean and his family. Of these four attractions, only two are based on real historical figures. The tales of Sawney Bean and his family of cannibals residing in the caves of rural Scotland are based entirely on myth and legend (Graham, 2010) as is the tale of Mary King's Ghost. These attractions are featured alongside two others based on fact, and this calls into question; where is the differentiation between fable and fact? In places of 'dark tourism', Lennon and Foley question whether “re-creation of objects, utilization of interpretive techniques and experimentation with identity adoption... displace real history behind a façade of education and historical narrative” (2000:152), ergo,in order for the audience to become fully immersed in the story of brave William Wallace, or evil Burke and Hare, or the terrifying Sawney Bean, the 'story' must be told in a spectacular fashion, which can often result in the displacement of historical fact. But in utilizing history as the commodity (Shaw and Williams, 2004) the producer must seek to enthral the consumer, and they do this by appealing to what they want to see, and as Hannigan (1998) points out, like it or not, tourists prefer the fictional and romanticised representations of history. This process of romanticising a factual representation can be seen as a 'spectacle'. DeBord, in his work on the society of the spectacle, views tourism as “the chance to see what has been made trite” (1992:130) and is damning in his view of what Miles and Miles (2004:96) refer to as 'fantasy narratives'. Ritzer (2008) also condemns the creation of spectacle through fantasy narratives, and the subsequent loss of historicity that is apparent in attractions such as the Dungeon. However, it can be argued that almost all of Edinburgh's horror heritage attractions still utilise fact along with fiction, but this is simply framed in a spectacular, immersive setting - Mercat Tours take participants to Edinburgh's underground vaults and allow their imaginations to run wild, but at the same time telling of how the people of Edinburgh lived in the middle ages; The Dungeon, which could be argued is an attraction in its most spectacular form, may convey fictional representation of mythical stories, but they still utilise factual characters to build stories, albeit spectacular ones. Participants may already have their perception of the characters, based on “dragging” (Rojek and Urry, 1997:54) already existing representations they have seen in the media, and the Dungeons build on this perception with immersive theming and stories; The guides at the Real Mary King's close, while still maintaining the 'ghost' story, in fact banish any perception participants may have had that the residents were 'shut-in' with the plague, stating this is only speculation, informing them that history shows that during these dark times, Edinburgh were in fact very good to their plague victims; The Horrible Histories Tour, arguably the least spectacular of all the attractions, utilises historical fact and the real sites in Edinburgh to tell their stories to children almost as jokes, in what Pine and Gilmore would call “edutainment” (1999:32). From these examples, we can deduce that though Edinburgh's horror heritage attractions often utilise myth and speculation to tell stories in a spectacular fashion, they do so by utilising historical fact as a means to anchor the story. It is not uncommon for a tourist place to over-express its underlying culture (MacCannell, 1999), and Edinburgh is no exception, framing fact and fiction (Rojek and Urry, 1997) to portray these dark times in a light-hearted (albeit often macabre), more accessible manner. Lennon and Foley (2000) argue that consideration should be given to situations where reality and representations are inconsistent with each other, and it is apparent that in such situations where there is the creation of a spectacular story based on historical fact, issues lie with authenticity. Many theorists would argue that the tourism industry currently resides in state where there are no loner authentic experiences, only staged authenticity (MacCannell, 1999; Urry, 2002; Rojek, 1993; Rojek and Urry, 1997). As previously demonstrated, many of Edinburgh's horror heritage attractions utilise theming and spectacular story telling to immerse their audiences, and these 'simulations' and 'replications' (Rojek, 1993; Lennon and Foley, 2000) represent a state of hyperreality, where reality alone is no longer enough (Eco, DATE). Edinburgh Dungeon simulates its representations as 'live' events, thus enabling a clear time-space compression (Rojek, 1993), where impact is key, but both producers and consumers acknowledge that this spectacular simulation is, what Pine and Gilmore (1999) deem, a 'real fake' in that producers make no claims that what occurs in intended to represent absolute reality. Mercat Tours and the Real Mary King's Close on the other hand, try to utilise existing infrastructure and 'the supernatural' to create an experience where imagination is key. MacCannell (1999) argues that tourists seek authentic experiences, however other authors disagree. Rojek and Urry (1997) point out that authenticity is no longer an issue under postmodernism, as the postmodern tourist seeks uniqueness, and according to Shaw and Williams (2004), the unique experience does not necessarily have to be authentic. Uniqueness is a largely contributing factor in the popularity of Edinburgh's horror heritage: the stories surrounding the hyperreal experiences of Mercat's ghost tours, Mary King's Close, the Dungeon's Sawney Bean or Burke and Hare attractions are all unique to Edinburgh. They are embedded through both fact and fiction in Edinburgh's culture. Rojek contends that the postmodern tourist consumption experience “is accompanied by a sense of irony. One realises that what one is consuming is not real, but nonetheless the experience can be pleasurable and exciting, even if one recognises that it is also 'useless'” (1993:134). However, are the experiences at Edinburgh's horror heritage attractions, which as previously discussed are frequently based on fact, completely useless? It can be argued that just by taking part, a tourist leaves educated, receiving a glimpse of history, albeit a commercialised one. The issue of authenticity versus commercialisation is highlighted by Miles and Miles (2004), and it seems clear that commercialisation is clearly evident in the case of Edinburgh's horror heritage. Using Edinburgh's Greyfriar's Kirkyard as a prime example, the site is the resting place of many famous Scots, including poet William McGonnegal and Walter Scott's father (Royal Mile, 2010). Though the kirkyard's most famous resident is undoubtedly Bobby the dog. The story of Bobby is well known, and has twice been made into film, and heavily romanticised (Eye for Film, 2010). The same could perhaps now be said for Burke and Hare, as their story became immortalised on film in 2010 in a John Landis comedy, where the characters were portrayed as loveable Irish buffoons who 'just couldn't help themselves' (Internet Movie Database, 2010). The film is what Pine and Gilmore (1999) would call a 'real fake'; it made no claims that the events depicted were fact other than the very basis of the story (Burke and Hare murdered people to sell their bodies to medical science for money). The film used comedy to overwrite the original meaning (Ringer, 1998), but while still giving a very base insight into the story. It seems fair to suggest that Edinburgh has made an attempt to capitalise on the film; Edinburgh Dungeon added its Burke and Hare attraction this year (Edinburgh Dungeons, 2010) and there have also been several Burke and Hare 'murder tours' established this year (McCracken, 2010). Some theorists, such as Ritzer (2008), condemn this commodification as 'Americanisation', while others see it as a collapse of cultural meaning (Greenwood, 1977). Arguably, the Burke and Hare film painted the serial killers in a more sympathetic light, and this image could risk tourists 'dragging' (Rojek and Urry, 1997) the portrayal as a true representation. However, Rojek, in his work on 'black spots' alludes to the fact that the commercialisation of such sites enables the tourist “to project themselves into the personalities, events and ways of life which have disappeared. But this projection could not be accomplished at all unless the personalities and ways of life were not so omnipresent in our culture through audio-visual media.” (1993:144). Ergo, it seems apparent that while commercialisation may present a romanticised and skewed vision of historical fact, it can be argued without such commercialisation to attract participants, the history would fade away. For Edinburgh's horror heritage, commercialisation is not always a bad thing; commercialisation can help keep the story alive, as long as historicity is not lost to spectacle. Tours such as the Real Mary King's Close and the Horrible Histories Bus Tour are commercial but they do not sacrifice historicity, instead they utilise it along with other light-hearted methods (like the supernatural or the telling of jokes) to actively immerse the tourist. Conclusion To conclude, it can be deduced that horror heritage plays an important role in Edinburgh's cultural tourism. With so many successful attractions, it is important to understand the industry in terms of its costs and benefits to the producers, consumers, and to Edinburgh itself. As stated, issues are apparent in the construction of the spectacle of horror heritage, as historical fact can be sacrificed in place of a greater story. Authenticity is an important issue, as producers must remember that while they are trying to immerse audiences, they are also simulating representations of history (though not necessarily reality) and should always remember to anchor them with historical fact at the risk of creating falsified constructions of an unreality. As previously stated, commercialisation can help to keep a story fresh in the minds of consumers which would otherwise fade away. It should also be remembered that the post-modern tourist is aware that what they see is not real – though some theorists would argue the lines between fact and fiction are becoming increasingly blurred, the differentiation still exists, and consumers know how to tell the difference without the need for historical fact to be separated from a “damn good story” (Mercat Tours Ltd, 2010). References British Attractions (2010), British Attractions [Online] Available: http://www.britishattractions.co.uk/edinburghdungeons/ [accessed 10/12/10] Bryman, A. (1995), Disney and his Worlds, London: Routledge Burke and Hare (2010), Internet Movie Database [Online] Available: www.imdb.com [accessed 10/12/10] City Sightseeing (2010) Horrible Histories Tour [Online] Available: http://www.edinburghtour.com/en/our-tours/city-sightseeing--multi-language-headphones.html [accessed 10/12/10] Cohen, S. and Taylor, L. (1976), Escape Attempts: the Theory and Practice of Resistance to Everyday Life, England: Penguin Books. DeBord, G. (1992), Society of the Spectacle, United Kingdom: Editions Gallimard Edinburgh Dungeon (2010), Edinburgh Dungeon [Online] Available: http://www.thedungeons.co.uk/edinburgh/en/index.htm [accessed 8/12/10] Edinburgh Royal Mile (2010), Greyfriar's Kirkyard [Online] Available: http://www.edinburgh-royalmile.com/interest/greyfriars-kirkyard.html [accessed 10/12/10] Editors for the Gazetteer for Scotland (2010), [Online] Available: http://www.scottishplaces.info/features/featurefirst8110.html [accessed 10/12/10] Education Plus (2010), Horrible Histories Bus Tour [Online] Available: http://education.scholastic.co.uk/content/1424 [accessed 10/12/10] Eye For Film (2010), Greyfriar's Bobby [Online] Available: http://www.eyeforfilm.co.uk/reviews.php?id=4459 [accessed 10/12/10] Greenwood, D. (1997) 'Culture by the Pound: an Anthropological Perspective on Tourism as Cultural Commoditization', in Smith, V.L. (ed), Hosts and Guests: the Anthropology of Tourism, London: Blackwell Hannigan, J. (1998), Fantasy City: Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis, Oxon: Routledge Jensen, R. (1999), The Dream Society: how the coming shift from information to imagination will transform your business, New York: McGraw Hill Lennon, J. and Foley, M. (2000), Dark Tourism: the Attraction of Death and Disaster London: Continuum. MacCannell, D. (1999), The Tourist: a new theory of the leisure class, London: University of California Press McCracken, E. (2010), Heritage of Horror, Herald Scotland [Online] Available: http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/home-news/heritage-of-horror-1.1063418 [accessed 8/12/10] Mercat Tours Ltd. (2010), Mercat Tours [Online] Available: http://www.mercattours.com/about-us.asp [accessed 8/12/10] Miles, S. and Miles, M. (2004), Consuming Cities, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan Pine, B.J. And Gilmore, J.H. (1999), The Experience Economy: work is theatre and every business is a stage, USA: Unknown Hughes, G. (1998), 'Tourism and the Semiological Realisation of Space', in Ringer, G. (ed) Destinations: Cultural Landscapes of Tourism, London: Routledge Ritzer, G. (2006), The McDonaldisation of Society, 5th ed, Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press Rojek, C. (1993), Ways of Escape, Basingstoke: MacMillian Rojek, C. and Urry, J. (1997), Touring Cultures: Transformations of Travel and Theory, London: Routledge Royal Mile (2010) Shaw, G. and Williams, A.M. (2004), Tourism and Tourism Spaces, London: SAGE Urry, J. (1990), The Tourist Gaze, London: SAGE