2A. Developmental teachers` reflective essays on motivation

advertisement

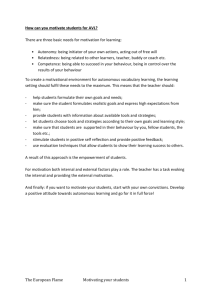

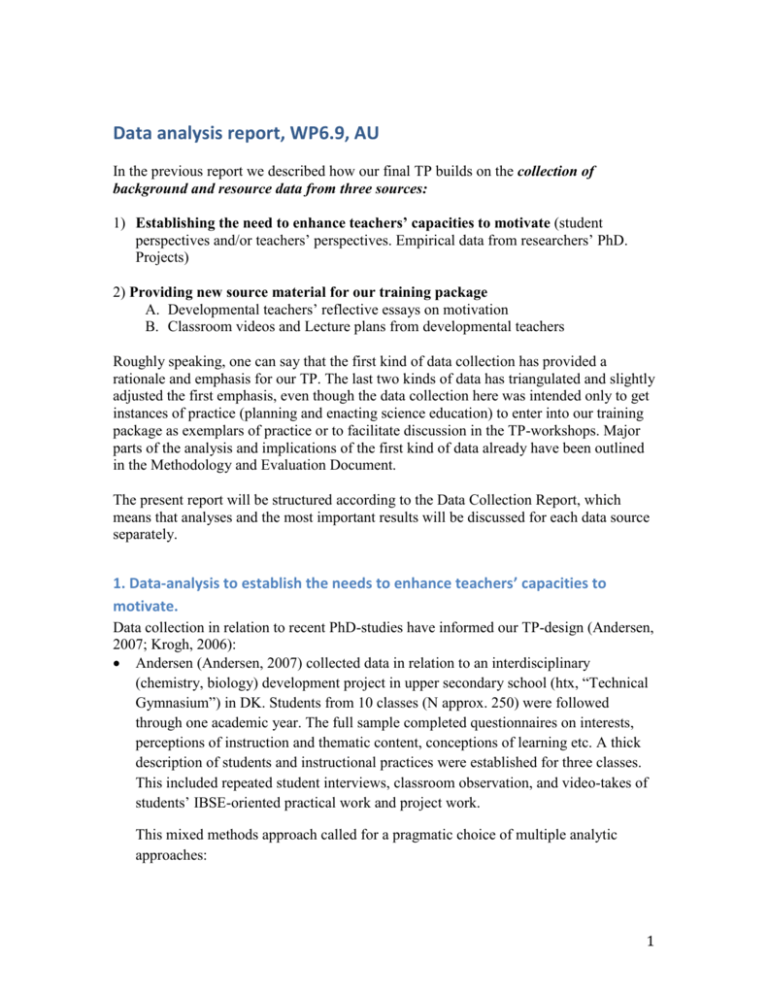

Data analysis report, WP6.9, AU In the previous report we described how our final TP builds on the collection of background and resource data from three sources: 1) Establishing the need to enhance teachers’ capacities to motivate (student perspectives and/or teachers’ perspectives. Empirical data from researchers’ PhD. Projects) 2) Providing new source material for our training package A. Developmental teachers’ reflective essays on motivation B. Classroom videos and Lecture plans from developmental teachers Roughly speaking, one can say that the first kind of data collection has provided a rationale and emphasis for our TP. The last two kinds of data has triangulated and slightly adjusted the first emphasis, even though the data collection here was intended only to get instances of practice (planning and enacting science education) to enter into our training package as exemplars of practice or to facilitate discussion in the TP-workshops. Major parts of the analysis and implications of the first kind of data already have been outlined in the Methodology and Evaluation Document. The present report will be structured according to the Data Collection Report, which means that analyses and the most important results will be discussed for each data source separately. 1. Data-analysis to establish the needs to enhance teachers’ capacities to motivate. Data collection in relation to recent PhD-studies have informed our TP-design (Andersen, 2007; Krogh, 2006): Andersen (Andersen, 2007) collected data in relation to an interdisciplinary (chemistry, biology) development project in upper secondary school (htx, “Technical Gymnasium”) in DK. Students from 10 classes (N approx. 250) were followed through one academic year. The full sample completed questionnaires on interests, perceptions of instruction and thematic content, conceptions of learning etc. A thick description of students and instructional practices were established for three classes. This included repeated student interviews, classroom observation, and video-takes of students’ IBSE-oriented practical work and project work. This mixed methods approach called for a pragmatic choice of multiple analytic approaches: 1 The questionnaires were analyzed using standard statistical methods within the SAS 9.1 software package. Means, group means, ANOVA’s, Pearson correlations, and clustering procedures were frequent. Student interview transcripts were analyzed using the Atlas.ti software package. Classroom Video’s were also analyzed within Atlas.ti allowing hermeneutic theory-building through interrelating of video instances, video transcripts, and interview instances. Most importantly, it was found that students’ motivation in the school science context could be largely understood in terms of Self-Determination Theory (SDT, (Deci & Ryan, 2002), with its emphasis on students’ sense of Relatedness, Autonomy, and Competence. In particular the Autonomy-dimension was found to influence students’ motivation. Generally, IBSE oriented approaches balancing student Autonomy and Learning Environment Structure tended to be motivational favorable. Teachers seemed to be largely un-aware of the motivational importance and implications of this dimension and its complex interaction with students’ sense of Competence. Relatedness was never designed for by teachers and only accidentally accomplished by students. Krogh (Krogh, 2006) integrated a series of studies from physics in upper secondary school (stx, “General Gymnasium”): o longitudinal survey-study of physics students (N=781) in first and second year of upper secondary school. Emphasis on students’ attitudes, and how these are shaped by instructional choices and cultural border crossings. Results have been reported in (Krogh & Thomsen, 2005) o web-based survey study of students’ general value-structure (N= 341), pursuing value-orientations as motivational filters and drives. o Integrative study of The Ethos of School Physics, using multiple data sources, including textbook analysis. o Two years of action research inquiring how students’ values/other life worlds influence their engagement with science, their instructional preferences etc. Thick description of students from one class in upper secondary physics (N=26). Again, a number of different analytic approaches were applied. o survey data were analyzed in standardized ways in SAS 9.1 (including factor analysis, and multiple regression procedures) o text-book analysis was conducted using an innovative new framework The Ethos of School Physics Analysis (TESSA). This framework was developed for analysis of student affordances in the classroom, using multiple types af empirical input. Obviously, it was re-operationalized for textbook analysis. 2 o rich data from the action research (e.g. interview transcripts) were analyzed by interpretive methods (e.g. using Atlas.ti). The most TP-relevant findings were: Factor analysis of survey data on students’ general values revealed 5 important value-orientations among urban youth in upper secondary school: o Relations (two orientations), ‘togetherness’ ‘identity-building’ o Autonomy/Self-Direction o Knowledge-Performance/Competence o Potentiation (exciting and stimulating experiences) According to value-theory such orientations are motivational constructs that guide students’ actions and choices in context. It can be argued that the first 4 of these correspond to the motivational “inner needs” of Self-Determination Theory. The research adds a situational component Potentiation to the SDT needs, but otherwise serves as an independent validation of this theory’s relevance for the description of modernized youth. The TESSA analysis based on all available empirical data from the Danish setting on subject Physics showed a marked orientation towards Epistemological closure (e.g. verification of pre-established theories following cook-book procedures), One-sided Communication (e.g. authoritative teacher monologue or IRE“dialogue”), a learning design emphasizing students’ individual work, a choice of content and subject approaches creating distance and strangeness to students’ lifeworlds, and finally a preference for addressing motivational problems with cognitive means. All aspects indicate that there are problems with IBSE- and motivational approaches in physics. Supplementary TESSA analysis demonstrated that school science subjects come in different flavors. Biology-teachers tend to design for motivation through social and varied learning opportunities, while physics teachers would rather provide challenge and cognitive drives. Neither of the two groups of teachers gave priority to activities with a high degree of student autonomy, e.g. IBSE-oriented approaches to practical work, e.g. open inquiry, problem-based learning or project-organized work. Together these data collections have informed our TP-design in the following aspects: Theoretical/motivational emphasis: 3 Science teachers tend to have very restricted motivational thinking and practices, derived from experience and craft-knowledge only. This suggests that introducing them to some propositional knowledge (“motivational theory”) may be beneficial. The ways in which teachers organize their learning environment, their communicative approaches, and the epistemological practices they implement in school sciences are major influences on students’ sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Improving teachers’ motivational awareness, reflexivity and practice within these areas might be the best way to improve students’ interest in school sciences Motivational benefits from the students’ perspective. The most relevant motivational theories emphasize students’ sense of autonomy, competence, relatedness. This suggests that Self-Determination Theory and the competence-oriented Efficacy-theory of Bandura (Bandura, 1997) should be introduced. IBSE-oriented approaches are easily aligned with SDT motivational emphases. This potential should be stressed through the use of course activities, examples, and tasks. Organization: The variety of science subject flavors suggests that teachers may benefit from discussions with teachers from other science subjects. 2A. Developmental teachers’ reflective essays on motivation As a part of their preparation for the trail version TPver1 the eight developmental teachers from different science subjects wrote an essay about why students’ motivation is important and what kind of strategies they use to motivate students. Further, they described a Good and a Bad Motivational Case from their own classroom. Good and Bad Motivational Cases: Case+: Describe a critical situation from your own teaching, where the students were very motivated. What was so motivating for students in that situation? Case-: Describe a critical situation from your own teaching, where the students were not motivated? What reasons were there for their lack of motivation? What could you possibly have done to change the situation? These essays indicate teachers’ initial ideas about students’ motivation and how teaching can stimulate or inhibit students’ motivation. They were analysed and used to characterise individual teachers’ ideas about motivation. 4 Table 1 shows that all eight teachers comment on the importance of the topic for students’ motivation and most teachers point to the motivational effect of relevance and students’ everyday life. On the other hand it has a negative effect if the topic is very theoretical or involves much mathematics (in physics) or chemistry (in biology). Most of the teachers also points to exiting activities as a vehicle for students’ motivation. These activities can differ, but most often teachers point to the inclusion of experimental work. Further, most of the teachers emphasize the importance of a varied use of teaching methods. Several teachers mention the negative motivational effect of science being a difficult subject, but only a single teacher sees students’ self-efficacy as an important aspect of students’ motivation in science. Less than half the teachers mention the learning environment and teacher’s interaction with the students as aspects having influence on students’ motivation and only a single teacher mention the motivational effect of students having influence on choice of topic and learning activities. When these teachers think about students’ motivation they primarily focus on interesting and relevant topics and how they can include exiting activities, primarily experiments. This is a rather narrow conception of how to motivate students, compared to the multiple strategies targetted by recent interventions (e.g. (Martin, 2008). Our analysis of teachers’ essay writing has reassured some of our TP-intentions based on the previous Ph.D. findings: Teachers tend to have a narrow range of motivational strategies, and several vital aspects seem to be completely or almost absent from their thinking. This suggests a multi-dimensional TP-intervention, with the introduction of several motivational theories. o autonomy and relatedness and how these aspects can be utilized for motivational purposes are absent – suggesting that these vital aspects be included in the TP. o Similarly, there is a need to stress the motivational importance of students’ self-efficacy and enhance teachers’ capacities to support students’ self-efficacy within science. Our essay-analysis has led to the addition of the motivational effects of topics and tasks to our TP – taking seriously teachers’ emphasis on these aspects (e.g. CatchHold theory, e.g. the concept of Task Value from Expectancy-Value theory). 5 Table 1. Teachers’ initial ideas about factors influencing students’ motivation (positive effect, negative effect) Kirsten (Female teacher) Topic and curriculum emphasis Exiting and relevant topic. Manhattan Project – interesting story Kristen (Male teacher) Everyday physics. History of physics Students’ own experiments and presentations Katrine (Female teacher) Topics of relevance ex. their own body. Hardcore subject matter. Chemistry in biology Lack of subject relevance Testing of blood Humoristic and type, special responsive. Not knowledge an oracle about their own body Karsten (Male teacher) Students’ selfefficacy Exiting activities Students’ selfefficacy and ability to master subject matter. Difficult subjects, former experience Students give lectures on topics of own interest Teacher’s role Learning environment Supporting students with lack of selfefficacy Safety and comfort Engaged and well prepared Organisation of the lesson External factors Students’ effort and persistence Variation in activities Students must Didactic have a feeling of teaching belonging – social and professional Influence on choice of topic or activity. Same module in several classes – standard teaching Variation in culture and competences. Anti-social students Inconvenient lesson hours A desire for high marks 6 Majken (Female teacher) Bjarning (Male teacher) Mette (Female teacher) Lotte (Female teacher) Topic and curriculum emphasis Students’ everyday knowledge and interests. Some aspects are necessary, but not interesting for the students Relevance for students’ everyday life. Green energy technology. Utility of science. Mathematical derivation in physics Students’ everyday life. Topics of interest Theoretical approach Students’ everyday life. Theory Students’ selfefficacy Exiting activities Teacher’s role Learning environment Organisation of the lesson External factors Experimental work. Play and physical activity. Small competitions between groups of students Show interest in students’ learning. Formative feedback. Fascination of the subject Good atmosphere and comfort in the classroom. Social and professional relationship Variation in activities according to learning stiles External motivation Inconvenient lesson hours. Use of computers Variation in activities. Active students Inconvenient lesson hours Variation in activities. Good structure. Active students. Visualisation Demand and registration of students’ presence Astronomy nights with students as presenters (experts). Small experiments and activities Difficult theory Students work with their own experiments Chemistry is a difficult subject. It is not interesting, if you don’t understand Independent work and own experiments. But activities doesn’t always stimulate students’ motivation to understand Personal relationship Demand and registration of students’ presence 7 2B. Classroom (and workshop) videos with developmental teachers Video data was collected from the trials of TPve1 with a developmental group of 8 teachers from various science subjects. They include: 2 classroom video-sessions with each teacher trialing/enacting motivational approaches (approx. 3 hour video tape with each teacher) 4 video-taped workshop-sessions where teachers presented and discussed instances/issues of motivational practice. 2 of these workshops were conducted as Video Clubs where teachers presented selected video clips from their own practice and for the purpose of shared reflection. Our data-analysis here reflects one of our purposes for collecting these video data: we wanted authentic video documentation to use as source for design of activities and discussions within the extended and redesigned TPve2. Consequently, our video analysis will focus on identifying “golden” video clips of value for teachers in the TP-context. The analysis is just at its onset, and the analytic framework is still in the making. Clearly, a deliberate analytic search through the videos calls for rationales, categories, and quality criteria of video clips for teacher training purposes. From theoretical considerations we have arrived at the following tentative classification of attractive video clips: Clip Category 1. Best Practice Rationale Explication of Best Practice. Exemplars for inspiration Vicarious experiences Structure Single clip 2. Critical Motivational Incidents 3. Student Motivation Awareness Motivational awareness Single clip 4. Enacting elements of motivational theories (SDT, Self-efficacy, taskvalue etc). Teachers’ reflection-onaction Prof. development (PD) Theory-in-action discussion Vicarious experiences PD Vicarious experiences Single clip Reflective contrasts & Reflection-on-action & discussion Composite 5. 6. Single clip (additional source framing) Composite (additional source video) (a number of Tentative Characteristics -Normative by nature. May tend to dampen critical discussion. -Difficult to find (even with an explicit normative system) -May have either student, teacher or interaction focus. -A situation where motivation is either recreated, reassured or slips away. -Clip should communicate enough context to enable discussion of why the outcome was produced. -Student focus. -Emphasis on potential motivational indicators and the diagnosis of individual students’ motivational states. -theoretical focus -needs framing through statements of teachers’ intentions from e.g. lesson plans or workshop presentations -Primary focus: teacher workshop focus - Sec. focus: Classroom incident as object for reflection -Thematically organized clips to facilitate reflection and discussion 8 distinctions clips) (e.g. discourse and uptake) As part of our analysis we will try to detail the characteristics of each type of useful clips. We imagine, that such work will be beneficial to future development of video supported teacher training – and consider studying the differential effects of various types and framings on teachers’ practices. The most concrete TP-result of this effort will be the inclusion of a number of videosupported exercises/activities in our revised TPve2. Our aim is to construct and include useful videos from the widest range of video-categories possible. 9 4 sider min 1500 ord Data, analysemetoder Resultater og findings Hvordan resultaterne har konsekvens for designet af vores training package Pre-data: Hvad er det vi har fundet i vores ph.d. arbejder (Lars) Lærernes essays. Hvorfor er motivation vigtigt, strategier ift, at motivere eleverne. Undervisning, der motiverer og eksempler på konkrete cases, hvor undervisningen eleverne har været motiverede/demotiverede (good and bad case) (Hanne intro skrivning om opgaven, analysen af deres skriverier resulterende i tabellen, overvejelsen i forhold til tabellen) Videoer fra lærernes undervisning. Udvælgelse kriterier for det gode videoclip. Konkret indhold i forhold til hvordan motivationsteorier kan implementeres i practice. Motivational Practice1 – her sker der noget på motivationsfronten (Vicarious experiences - enacting2) eller Grundlag for Reflectioner (reflection - flere praksiser overfor hinanden eller refleksion over hvad er den alternative practice)3. Skærpet opmærksomhed og videoer, og clips der illustrerer elevmotivation. Forskellige typer af læreres behov. Grad af framming, hvad er vinklen/forhistorien både i forhold til undervisningssituationen og lærerens tænkning om god og motiverende undervisning Udvælgelse af clips, der kan bruges til afprøvning af formatet for formidlings-clips /kursusmateriale (refleksionsopgaver) Ikke best practice Clack and Holingworth 3 Task value – hverdagserfaringer (Kristen). Autonomi og kontrol (Bjarning og Kirsten) 1 2 10