2.3 linear differential equations

advertisement

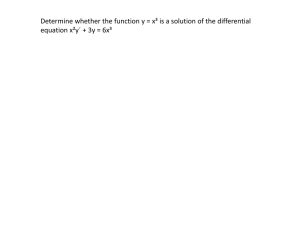

A very brief introduction to differential equations Shatha Sattar 1. Introduction Many of the laws of nature- in physics, in chemistry, in biology, in engineering, and in astronomy- find their most natural expression in the language of nature. applications of differential equations also abound in mathematics itself, especially in geometry and harmonic analysis and modelling. Differential equations occur in economics and systems science and other fields of mathematical science. 2. Basic concepts 2.1 ordinary differential equations A differential equation is an equation involving an unknown function and its derivatives. An example is 𝑑𝑦 = 5𝑥 + 3 𝑑𝑥 A differential equations is an ordinary differential equation if the unknown function depends on only one independent variable. If the unknown function depends on two or more independent variables, the differential equation is a partial differential equation. 2.2 order and degree The order of a differential equation is the order of the highest derivative appearing in the equation The degree of a differential equation that can be written as a polynomial in the unknown function and its derivatives is the power to which the highest –order derivative is raised. 2.3 linear differential equations An nth- order differential equation in the unknown function y and the independent variable x is linear if it has the form 𝑑𝑦 𝑑𝑛−1 𝑦 𝑑𝑦 𝑏𝑛 (𝑥) 𝑑𝑥 + 𝑏𝑛−1 (𝑥) 𝑑𝑥 𝑛−1 + ⋯ + 𝑏1(𝑥) 𝑑𝑥 + 𝑏0 (𝑥)𝑦 = 𝑔(𝑥) 1 ( ∗) The functions 𝑏𝑗 (𝑥) (𝑗 = 0,1,2, … , 𝑛) and 𝑔(𝑥) are presumed and depend only on the variable 𝑥.differintial equations that cannot be put into the form (*) are nonlinear. 3. Solutions 3.1 definition of solution A solution of a differential equation in the unknown function y and the independent variable x on the interval I is a function y(x) that satisfies the differential equation identically for all x in I. 3.2 particular and general solutions a particular solution of a differential equation is any one solution. The general solution of a differential equation is the set of all solutions. 3.3 Initial-value problems. Boundary value problems A differential equation along with subsidiary conditions on the unknown function and its derivatives, all given at the same value of the independent variable, constitutes an initial problem. The subsidiary conditions are initial conditions. If the subsidiary conditions are given at more than one value of the independent variable, the problem is boundary –value problem and the conditions are boundary conditions. A solution to an initial-value or boundary –value problem is a function y(x) that both solves the differential equation and satisfies all given subsidiary conditions. 4. Classification of first-order differential equation 4.1 standard form and differential form The standard form of a first-order differential equation is 𝑦 ′ = 𝑓(𝑥, 𝑦) (4.1) the function f(x,y) given in (4.1) can always be written as the quotient of two other 𝑑𝑦 functions M(x,y) and -N(x,y). Thus, recalling that 𝑦 ′ = 𝑑𝑥 , we can rewrite (4.1) as 𝑀(𝑥, 𝑦) ⁄−𝑁(𝑥, 𝑦) , which is equivalent to the differential form 2 𝑑𝑦 𝑑𝑥 = M(x,y) dx + N(x,y) dy=0 (4.2) 4.2 exact equations A differential equation M(x,y) dx + N(x,y) dy=0 Is exact if there is a function g(x,y) such that dg(x,y)= M(x,y) dx + N(x,y) dy test for exactness: if M(x,y) and N(x,y) are continuous functions and have continuous first partial derivatives on some rectangle of then xy - plane then (4.2) is exact if and only if 𝜕𝑀(𝑥,𝑦) 𝜕𝑦 = 𝜕𝑁(𝑥,𝑦) 𝜕𝑥 4.3 separable equations Consider a differential equation in differential form (4.2). if M(x,y) = A(x) ( a function only of x ) and N(x,y) = B(y) ( a function only of y ), then A(x) dx + B(y) dy = 0 (#) The solution to (#) is ∫ 𝐴(𝑥)𝑑𝑥 + ∫ 𝐵(𝑦)𝑑𝑦 = 𝑐 Where c represents an arbitrary constant. 4.4 homogeneous equation A differential equation 𝑦 ′ = 𝑓(𝑥, 𝑦) is homogeneous if f(tx,ty) = f(x,y) For every real number t. Substitute y = xv And the corresponding derivative 𝑑𝑦 𝑑𝑣 =𝑣+𝑥 𝑑𝑥 𝑑𝑥 3 After simplifying, the resulting differential equation will be one with variables ( v and x ) separable , which can be solve by the separable method. 4.5 linear equations consider a differential equation in standard form . if f(x,y) can be written as f(x,y) = - p(x)y + q(x) (**) (that is, as a function of x times y, plus another function of x) the differential equation is linear . First – order linear differential equation can always be expressed as 𝑦 ′ + 𝑝(𝑥)𝑦 = 𝑞(𝑥) 5. second- order linear homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients 5.1 the characteristic equation Corresponding to the differential equation 𝑦 ′′ + 𝑎1 𝑦 ′ + 𝑎0 𝑦 = 𝑜 (1) In which 𝑎1 and 𝑎0 are constants, is the algebraic equation 𝜆2 + 𝑎1 𝜆 + 𝑎0 =0 (2) Which is obtained from (1) by replacing𝑦 ′′ , 𝑦 ′ , and 𝑦 by 𝜆2 , 𝜆 and 𝜆0 = 1, 𝑟𝑒spectively. Equation (2) is called the characteristic equation of (1). 5.2 solution in terms of the characteristic roots the solution of (10 is obtained directly from the roots of (3). There are three cases to consider. Case 1. λ1 and 𝝀𝟐 both real and distinct. Two linearly independent solutions are 𝑒 𝜆1 𝑥 and 𝑒 𝜆2 𝑥 , and the general solution is y=𝑐1 𝑒 𝜆1 𝑥 + 𝑐2 𝑒 𝜆2 𝑥 4 Case 2. λ1 = a + ib, a complex number . since a1 and a0 in (1) and (2) are assumed real, the roots of (2) must appear in conjugate pairs; thus, the other roots is λ2 = a – ib. two linearly independent solutions are 𝑒 (𝑎+𝑖𝑏)𝑥 and 𝑒 (𝑎−𝑖𝑏)𝑥 , the general solution is y= 𝑑1 𝑒 (𝑎+𝑖𝑏)𝑥 + 𝑑2 𝑒 (𝑎−𝑖𝑏)𝑥 Case 3. λ1 = λ2 . Two linearly independent solutions are 𝑒 𝜆1𝑥 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑥𝑒 𝜆2 𝑥 , and the general solution is y=𝑐1 𝑒 𝜆1 𝑥 + 𝑐2 𝑥𝑒 𝜆2 𝑥 6. nth –order linear homogeneous differential equations with constant coefficients The differential equation of the nth-order is 𝑦 (𝑛) + 𝑎𝑛−1 𝑦 (𝑛−1) + ⋯ + 𝑎1 𝑦 ′ +𝑎0 𝑦 = 𝑜 (*) Where 𝑎𝑗 ( j= o,1,2,…,n-1) is a constant . the characteristic equation associated with (*) is 𝜆𝑛 + 𝑎𝑛−1 𝜆𝑛−1 + ⋯ + 𝑎1 𝜆 + 𝑎0 =0 It is obtained from (*) by replacing 𝑦 (𝑗) by 𝜆𝑗 ( j= o,1,2,…,n-1) . In theory it is always possible to factor the characteristic equation , but in practice this can be extremely difficult , especially for differential equations of high order.in such cases, one must often use numerical techniques to approximate the roots or develop other methods of solution. 7. Linear differential equations with variable coefficients We are interested in the second -order linear homogeneous equation 𝑏2 (𝑥)𝑦 ′′ + 𝑏1 (𝑥)𝑦 ′ + 𝑏0 (𝑥)𝑦 = 𝑜 Dividing by 𝑏2 (𝑥), we can rewrite (*1) (*1) as 𝑦 ′′ + 𝑃(𝑥)𝑦 ′ + 𝑄(𝑥)𝑦 = 𝑜 5 (*2) Where P(x) = 𝑏1 (𝑥) 𝑏2 (𝑥) and Q(x) = 𝑏0 (𝑥) 𝑏2 (𝑥) , and it is assumed that P(x) and Q(x) are not both constants. 7.1 analytic functions A function f(x) is analytic at 𝑥0 if its Taylor series about 𝑥0 , ∞ 𝑓 (𝑛) (𝑥 − 𝑥0 )𝑛 ∑ 𝑛! 𝑛=0 Converges to f(x) in some neighbourhood of 𝑥0 . 7.2 ordinary points and singular points The point 𝑥0 is an ordinary point of the differential equation (*2) if both P(x) and Q(x) are analytic at 𝑥0 . If either of these functions is not analytic at 𝑥0 , then 𝑥0 is a singular point of (*2). The point 𝑥0 is regular singular point of (*2) if (1) 𝑥0 is a singular point of (*2) and (2) both functions (𝑥 − 𝑥0 )𝑃(𝑥) 𝑎𝑛𝑑 (𝑥 − 𝑥0 )2 Q(x) are analytic at 𝑥0 . Singular points which are not regular are called irregular. Theorem: if 𝑥0 is an ordinary point of (*2) , then the general solution in an interval containing 𝑥0 is 𝑛 ∑∞ 𝒏=𝟎 𝒂𝒏 (𝑥 − 𝑥0 ) = 𝑎0 𝑦1 (𝑥) + 𝑎1 𝑦2 (𝑥) Where 𝑎0 and 𝑎1 are arbitrary constants and 𝑦1 (𝑥) and 𝑦2 (𝑥) are linearly independent functions analytic at 𝑥0. References 1. Earl A. coddington – an introductions to ordinary differential equations. 2. George F. Simmons . Steven G. Krantz – differential equations theory , technique, and practice. 6 7