Zahedi, Badie and Curtis

advertisement

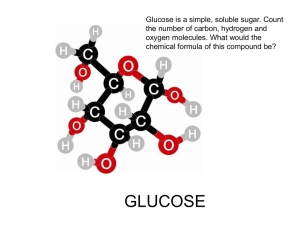

The Effect of Aspartame on Blood Sugar Level in Humans, Homo sapiens Mindy Zahedi, William Badie, Josh Curtis Department of Biological Sciences Saddleback College, Mission Viejo, CA 92692 Aspartame is an artificial non-saccharide sweetener used as a substitute for sugar in numerous foods and beverages. However, the safety of this product has been under scrutiny because of its link to cancer, fibromyalgia, brain damage and its effects of blood glucose levels. In this study, the effects of Equal Zero Calorie Sweetener, an artificial sweetener that contains aspartame, and Domino Pure Cane Sugar, was examined on the blood sugar levels of Homo sapiens. It was hypothesized that aspartame would raise blood glucose levels higher than sugar. Fifteen subjects had their blood glucose levels recorded every 15 minutes for 75 minutes after consumption of water, sugar or aspartame. The peaks caused by each of the substances were recorded and compared. The average blood peak was 91.6 mg/dL after consuming water, 120.1 mg/dL after consuming water with sugar and 116.6 mg/dL after consuming aspartame with water. An ANOVA test showed a statistical difference with a p-value of 2.1x10-10. When a post hoc test was run, there was a significant difference between the peak of blood glucose levels in sugar and aspartame when compared to water. However, there was no significant difference between the blood glucose level peaks of sugar and aspartame resulting in the hypothesis being rejected. Introduction Aspartame is a synthetic nonnutritive sweetener commonly used in low and reduced-calorie foods and beverages. The artificial sweetener has become part of the lifestyle of millions of men and women who desire to have better overall health, manage their weight, or appreciate the countless low- or reduced-calorie products available. Aspartame is currently consumed by more than 200 million people and found in over 6,000 products (Hankey and Lean, 2004). A key characteristic of aspartame is its ability to sweeten foods and drinks without adding calories (Robb-Nicholson and Schatz, 2004). Aspartame has become a healthier substitute for pure cane sugar that many people utilize. However, the popularity of the artificial sweetener has also raised debate about its health hazards. This, in turn, has led to countless studies about its safety and overall benefit as a common staple in our diet. Aspartame is one of the most thoroughly studied food ingredients, with more than 200 scientific studies supporting its safety including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Iuliano, 2010). Other scientific researchers found that aspartame has a potential for adverse effects (Briffa, 2005; Yellowlees, 1983). Aspartame is unique among lowcalorie sweeteners in that it is completely broken down by the body into its components – the amino acids, aspartic acid and phenylalanine, and a small amount of methanol. Each of these components can have extremely negative effects on the human body. Aspartic acid may cause neurological disorders, phenylalanine can cause serious brain damage to those with phenylketonuria, methanol breaks down into formaldehyde (a deadly neurotoxin) within the body and a large amount of amino acids may allow too much calcium in brain cells (Magnuson et al., 2007). Among these dangers is the risk of aspartame raising blood glucose to levels higher than pure cane sugar would. Over time, high sugar levels damage the body and can lead to the multiple health problems associated with diabetes. Those trying to maintain their weight or control their blood sugar levels, such as diabetics, may reach to artificial sweeteners with aspartame as an aid. If aspartame does indeed raise blood glucose levels more than regular sugar, than it could pose a danger to unaware diabetics (Hooper, 1968). This study will focus on the effect of aspartame on blood glucose levels. Comparing blood sugar levels in humans (Homo sapiens) consuming pure cane sugar and aspartame individually will be an effective way to analyzing if aspartame has a negative effect on blood glucose levels. For this study Domino Pure Cane Sugar and Equal Zero Calorie Sweetener will be utilized. The investigators hypothesize that the aspartame will cause a higher spike in blood sugar levels than the pure cane sugar in Homo sapiens. Materials and Methods The project took place throughout April 2014 in Saddleback College. Fifteen subjects between the ages of 18 and 30 were asked to participate. Each subject was required to meet up with the researchers on three different occasions, for three tests. For the first test, subjects were required to fast for 12 hours and report to the researcher, Mindy Zahedi’s house at 9:00 AM. Upon their arrival each subject had their blood glucose levels measured. Blood Glucose was measured by first wiping the subject’s finger with an alcohol swab, applying a new One Touch lancet to a One Touch lancing device and then using the lancing device to draw the subject’s blood. A TrueResult blood glucose monitor and TRUEtest test strips were used to obtain their blood glucose levels in mg/dL. After the initial glucose level was measured the subjects were required to drink 250 mL of water. After each subject finished their water they had their blood glucose levels taken every 15 minutes for an hour and 15 minutes. The fifteen subjects were asked to fast again for 12 hours and then report to the same researcher’s house at 9:00 AM. When they arrived they had an initial blood glucose level taken. They then had to drink 250 mL of water with 20 g of Equal Zero Calorie sweetener dissolved in it. Every 15 minutes after the subject had consumed his/her water with Equal Zero Calorie sweetener; they had their blood glucose level checked every 15 minutes for an hour and 15 minutes. Once again, subjects were asked to fast for 12 hours and then report to the researcher’s house at 9:00 AM. When they arrived they had an initial blood glucose level taken and then drank 250 mL of water with 20 g of Domino Premium Pure Cane Granulated sugar dissolved in it. Once they had finished consuming the water their blood glucose levels were measured every 15 minutes for an hour and fifteen minutes. Table 1. Blood glucose peaks of each subject for water, sugar and Equal Subject # water Equal sugar 1 84 121 92 2 106 128 104 3 91 119 121 4 93 124 118 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 81 84 76 82 102 92 90 105 91 92 105 116 121 119 122 112 123 117 122 118 120 120 96 123 119 101 122 121 114 126 139 122 132 When an analysis of variance (ANOVA) Single Factor test was ran, it showed that there was a significant difference between the three different groups (p= 2.1x10-10, ANOVA) as shown in Figure 1. A post hoc test was ran, its results revealed that there was a significant difference between the average blood glucose peaks of the water samples when compared to both the Equal (p<0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Correction) and Domino Sugar samples (p<0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the blood sugar peak of Equal artificial sweeteners and Domino Sugar. Average Blood Glucose Peak (mg/dL) Results The subjects that ingested Equal had an average blood glucose peak of 120.13±0.96 mg/dL while those who ingested Domino sugar had an average blood glucose peak of 116.67± 3.39 mg/dL. Additionally, the subjects who ingest regular tap water had an average blood glucose peak of 91.60 ± 2.43 mg/dL as shown in Table 1. 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Water Equal Domino Sugar Substance Ingested Figure 1. Mean peak blood glucose level for water, Equal zero calorie sweetener with aspartame, and Domino pure cane sugar. There is no statistical difference between the peaks caused by Equal and sugar, however there is a statistical difference for water when compared to Equal and water when compared to sugar. (P= 2.1x10-10, ANOVA and Bonferroni correction) Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Discussion The peak blood glucose levels when subject’s ingested water, sugar and the artificial sweetener with aspartame, when compared, showed significant statistical difference. When subjects ingested the control group, plain water, and their glucose levels stayed relatively stable and for some it decreased. When the subjects ingested the water with 20 grams of sugar their glucose levels spiked relatively quick, within 15-30 minutes. It was the same case when subjects ingested the Equal artificial sweetener. The artificial sweetener spiked within 15-20 minutes and continued having steep declines once the peak was reached. Statistical difference was shown when sugar or Equal was compared to water, as both caused a spike in glucose levels and water did not. However, when Equal was compared to sugar, there was no significant statistical difference. This caused the researchers to reject the hypothesis. Equal did indeed cause a spike in glucose levels, but the spike was no higher than the spike that normal pure cane sugar caused. A study with similar intentions was done by students on mice. The students studied the results of a life-long exposure to aspartame on several mice. They noticed that fasting blood glucose levels had been raised to higher levels when compared to levels taken before their exposure. They also noted that males had experienced more of an elevation in glucose levels than females. (Collison KS. Et al., 2012). Potential follow up studies may test the effects of long term aspartame ingestion on blood glucose levels. This may be done by requiring subjects to eat or drink a certain amount of sweetener with aspartame for a month while closely monitoring blood glucose levels. Another possible study may test the effect of aspartame consumption on males versus the effect of aspartame on females. Acknowledgments The researchers appreciatively acknowledge Professor Steve Teh and Dr. Tony Huntley for their countless lab hours and assistance. The researchers would also like to thank Saddleback College’s Department of Biological Sciences for their generosity and contribution of equipment. Literature Cited Briffa, J.,Gordon,I.J., Finer, N., Lean, M., Hankey, C.R. 2005, Aspartame And Its Effects on Health. The British Medical Journal , 330 (7486): 309-310 Collison, K. S., Makhoul, N.J., Zaidi M.Z. 2012, Gender Dimorphism in Aspartame-Induced Impairment of Spatial Cognition and Insulin Sensitivity. PLoS ONE, 7(4): 315-317. Hooper, B.M. 1968, Measuring Blood Sugar. The British Medical Journal, 4(5633): 774-776 Iuliano, J. 2010, Killing Us Sweetly: How to Take Industry Out of the FDA. Journal of Food Law & Policy, 6(1):31-87. Lean, M. and Hankey, C.R. 2004, Aspartame And Its Effects On Health. The British Medical Journal, 329 (7469): 755-756 Magnuson, B. A., Burdock, G. A., Doull, J. J. (2007). Aspartame: A Safety Evaluation Based on Current Use Levels, Regulations, and Toxicological and Epidemiological Studies. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 37(8): 629-727. Robb-Nicholson, C. and Schatz, N.A. 2004, Artificial sweeteners: Okay in moderation. Harvard Women’s Health Watch, 11(11):2-3 Yellowlees, H. 1983, Aspartame. The British Medical Journal, 287 (6396): 912-913