``Those [women] who feel strong and hope to find employment, a

advertisement

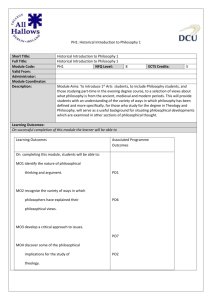

![``Those [women] who feel strong and hope to find employment, a](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006803801_1-09d402bda4c5e3f9e109bce74371c1a0-768x994.png)