Student Name Student Name Mr. Campolmi Honors English III 16

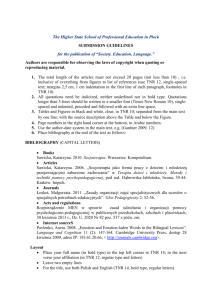

advertisement

Student Name 1 Student Name Mr. Campolmi Honors English III 16 October 2015 Feral Cat Population Management When a cat is released into the wild, it breeds, breeds, and breeds again. Each offspring branches off to breed, and the population gradually spirals out of control. The United States feral cat population is now estimated at 50 million, though some say the population is even greater than that (Williams). The cats are seen as a nuisance and a public and environmental health threat, as they loudly fight in neighborhoods, leave odors when marking their territory, carry disease, and kill vulnerable bird species (Williams; LaCroix). It is clear that the population must be controlled, and there are two dominant methods of doing so: trap, neuter, release (TNR) and trap and kill. Despite these options, governmental agencies ignore the burgeoning feral cat population, leaving the problem unresolved (Levy and Crawford). Local governments should subsidize TNR programs to stabilize and, therefore, reduce feral cat populations. Not all outdoor cats are feral cats; ferals can be defined as cats who were “once domesticated, but were abandoned, lost, or ran away” (LaCroix). The first generation of cats in the wild is termed “stray,” while following generations are “feral.” Adult ferals cannot be domesticated, but kittens can and are often brought into adoption programs. Even so, this does not slow population growth because females have two to three litters per year. They have an estimated lifespan of two years when alone, but they typically live much longer within a colony of ferals (LaCroix). As mentioned before, feral cats are a concern to public health and local Student Name 2 wildlife. They are known to carry rabies, fleas, Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) (Levy and Crawford). In regards to ecology, feral cats are defined as an invasive species, killing billions of small animals yearly (Figura). With this in mind, it is agreed that feral cat overpopulation is a problem, but there is controversy over how to solve that problem in an effective, practical, and humane manner (Levy and Crawford). TNR became popular in the 1990s and is widely used today by volunteer organizations. Cats are trapped, spayed or neutered, vaccinated for rabies, and returned to their home environment or adopted. Their ear is also clipped to identify them as sterilized. The other common method is trap and kill, in which cats are trapped and brought to a shelter for euthanization (LaCroix). A network of volunteer organizations carries out TNR, though a bill was recently proposed in New York to fund their efforts. Money would come from the New York’s Animal Population Control Program, which raises money primarily from dog license fees. This new legislation would take 20% of the money raised annually by the program, and $1 million was raised in 2014. The State Assembly passed the bill in May 2015, though it is awaiting vote in the State Senate (Campbell). If this bill is passed, it could serve as a model for other governments in need of feral cat population management. Local governments should subsidize TNR because it effectively stabilizes feral cat populations, as seen in several notable studies. Beginning in 1991, the University of Florida conducted an eleven-year study to evaluate the effectiveness of a TNR program. A complete census of cats was completed in 1996, and 68 cats were recorded. Of that population, all but one feral cat was neutered. By the end of the study period in 2002, 23 cats remained, reflecting a 66% reduction in the population. No kittens had been observed since 1995 (Levy, D. Gale, and L. Gale). This program accomplished the goals of an ideal TNR program, as it sterilized all of Student Name 3 the original colony, with one exception. TNR prevented further reproduction, resulting in natural attrition and eventual success in stabilizing the population. A similar two-year study was conducted at Texas A&M University in 1998. A total of 158 cats were involved in the study, with 123 captured the first year and 35 captured the second year. Furthermore, during the first year, 20 of the captured cats were kittens, while only 3 were kittens the second year. The latter were unlikely to have been born on campus, “as no littermates or nursing females were seen” (Hughes and Slater). TNR was once again successful in this program, as the number of captured cats decreased significantly between the two years of study. Due to the fact that no new kittens were born on campus, it can be concluded that reproduction and population growth had been halted by TNR. In both of these studies, many of the more tame and sociable cats could be removed for adoption (Levy, D. Gale, and L. Gale; Hughes and Slater). This additional step in TNR helps to further limit feral cat populations. TNR should be subsidized as it is known to improve various aspects of a feral cat’s health. In another study conducted by researchers of the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine, the body condition of feral cats was evaluated before and after neutering. At the beginning of the study, 54 percent of the cats were thin or underweight, but a year after neutering, only 14 percent were underweight (Scott et al.). An increase in weight reflects progression towards a more ideal state of health and improved welfare. Additionally, TNR protects cats from rabies. Ideally, a rabies vaccine is followed with boosters in subsequent years, but it has been observed that “a single dose of rabies vaccine protect[s] domestic cats against virulent challenge 4 years later” (Levy and Crawford). During the process of TNR, cats are vaccinated against rabies, protecting not only them, but also other unvaccinated cats. As more cats are vaccinated, the virus has fewer victims to which it can spread. Lastly, in Dr. Felicia B. Student Name 4 Nutter’s dissertation on the effectiveness of TNR programs, she finds that sterilized ferals “live significantly longer than their breeding counterparts” (Nutter). The short lifespan of feral cats can be attributed to “[t]he risks of disease, injury from fighting, [and] malnutrition” (LaCroix). TNR helps to solve these problems and allows feral cats to live longer and healthier lives. Government subsidization of TNR would be very cost-effective because TNR procedures already cost very little. According to Libby Post, executive director of the New York State Animal Protection Federation, trapping and killing costs $100 to $125 per cat and TNR is $35 to $55 per cat (Figura). Due to the fact that population control must be conducted on a large scale, utilizing TNR would save a large amount of money. More cats could be sterilized than euthanized when given a set subsidy. Furthermore, a large network of volunteer organizations dedicated to TNR already exists across the country. Post asserted that the aforementioned New York legislation would “bolster” the efforts of volunteer organizations (Figura). People would not have to be hired to implement TNR, as volunteers could continue to do so with subsidization. Most importantly, no additional money would be required to subsidize TNR programs. In New York’s proposed bill, money comes from the Animal Population Control Program, which, as said before, generates funds from dog license fees. This system could be implemented in all states, as “nearly all major municipalities require licensing” (Giordullo). The public is required to pay no more money than they already do, and the money will be used to efficiently manage the feral cat population. Local governments should subsidize TNR because the use of TNR benefits the community. Members of the community have complained that feral cats are a nuisance, but “neutering […] alters certain behaviors, making cats less likely to roam, spray, and fight” (Hughes and Slater). As the use of TNR is encouraged and increased, there will be less cause for Student Name 5 complaints and the feral cats will cease to be a community disruption. In the previously discussed study on feral cats’ body condition, it was unanimously observed that cats were friendlier and less aggressive after neutering, which could help to eliminate the stigma of unpleasant feral cats (Scott et al.). Though feral cats have the potential to carry FeLV and FIV, “the concern over diseased feral cats is largely aesthetic, a large group of diseased cats being more objectionable to people than a large group of healthy cats” (LaCroix). The transmission of FIV and FeLV is reduced with TNR, as cats fight less and cannot pass it to offspring (Levy and Crawford). Concerns to public health are thus diminished as TNR is implemented. As with any other scenario involving government subsidization, public opinion is taken into account. Public opinion is largely in favor of TNR (see figure 1), therefore, the decision to subsidize TNR would appeal to the community’s beliefs. Public Opinion of TNR - Georgia, 2012 Agree Disagree Undecided/Other 100% Response Rate 81% 80% 65.60% 60% 42% 40% 40% 20% 25.70% 14% 5% 36% 23% 25% 13% 8.70% 0% Letting a feral cat More effective You would donate live is more management of money to support humane than feral cats is needed TNR euthanizing it Statements Fig. 1. Public Opinion of TNR. (Chu and Anderson; Loyd and Hernandez) You would prefer tax-payer money to be spent on TNR as opposed to trap and kill Student Name 6 Despite the several benefits of implementing TNR, others support trap and kill as the best population management option. Critics of TNR claim that euthanizing feral cats is more effective in reducing the population. However, in a phenomenon known as the vacuum effect, “removing feral cat populations […] opens up the habitat to an influx of new cats, either from neighboring territories or born from survivors” (“The Vacuum Effect”). As the population rebounds, cats will continually have to be trapped and killed, consuming more time and money in the process. Cats that are sterilized during TNR cannot repopulate, resulting in permanent population reduction. Those opposed to TNR also believe that feral cats are a threat to public health and view euthanization as a way to eliminate this threat. Rabies draws considerable concern, but “90% of cases of rabies occur in […] raccoons, skunks, coyotes, foxes, and bats,” and the last reported case between a cat and human in the United States was in 1975 (Levy and Crawford). As discussed previously, vaccinations during TNR “provid[e] long-lasting herd immunity, even when individual animals [receive] only a single dose of vaccine and when only a portion of the population [is] immunized” (Levy and Crawford). In the process of trap and kill, no cats are vaccinated, allowing any survivors to continue to spread rabies. FeLV and FIV, deemed “aesthetic” threats, are also restricted by TNR, but not by trap and kill (LaCroix; Levy and Crawford). In her letter to New York Senator Kathleen Marchione, Janet M. Scarlett, an Emerita Professor of Epidemiology at Cornell University, dismisses any potential threats to public health as “minimal” by asserting that “[i]f this were not so, CDC and state health departments would have major programs to reduce cat populations” (Scarlett). Lastly, one of the more prevalent arguments for the use of trap and kill is that feral cats devastate local wildlife, most notably bird species. According to Scarlett, this phenomenon is hard to study because “there are confounding variables such as human development, habitat destruction, and other predators” (Scarlett). Student Name 7 Moreover, trap and kill does not effectively reduce the population and consequently will not decrease predation. Though some view trap and kill as a logical approach to population control, it lacks TNR’s effectiveness and consideration of public and wildlife health concerns. As the feral cat population burgeons and precipitates issues within the community, the need for population management becomes more apparent. To combat this, local governments should encourage the use of TNR through feasibly obtained subsidization. It has proved to be an successful, economical method that benefits both the cats and the people who come in contact with them. Unlike trap and kill, TNR permanently stabilizes and reduces feral cat populations while also curtailing disease transmission. Public support for TNR is evident, but financial endorsement from the government is necessary in reinforcing resolution efforts. Student Name 8 Works Cited Campbell, Jon. "Feral Cat Bill Claws Way through New York Legislature." Pressconnects. Press & Sun Bulletin, 11 June 2015. Web. 07 Sept. 2015. Chu, Karyen, and Wendy M. Anderson. U.S. Public Opinion on Humane Treatment of Stray Cats. Rep. Alley Cat Allies, Inc, 2007. Web. 7 Oct. 2015. Figura, David. "Feral Cat Bill Would Fund 'trap-neuter-release' Efforts across NY State." Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group, 29 May 2015. Web. 07 Sept. 2015. Giordullo, Staci. "Cat and Dog License Policies Draw Mixed Reviews." Angie's List. Angie's List, 06 July 2010. Web. 04 Oct. 2015. Hughes, Kathy L., and Margaret R. Slater. "Implementation of a Feral Cat Management Program on a University Campus." Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 5.1 (2002): 15-28. Web. 27 Sept. 2015. LaCroix, Anthony E. "Detailed Discussion of Feral Cat Population Control." Animal Legal and Historical Center. Michigan State University College of Law, 2006. Web. 14 Sept. 2015. Levy, Julie K., and P. Cynda Crawford. "Humane Strategies for Controlling Feral Cat Populations." Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225.9 (2004): 1354-360. AVMA. American Veterinary Medical Association, Aug. 2010. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. Levy, Julie K., David W. Gale, and Leslie A. Gale. "Evaluation of the Effect of a Long-term Trap-neuter-return and Adoption Program on a Free-roaming Cat Population." Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 222.1 (2003): 42-46. AVMA. American Veterinary Medical Association, Aug. 2010. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. Student Name 9 Loyd, Kerrie Anne T., and Sonia M. Hernandez. "Public Perceptions of Domestic Cats and Preferences for Feral Cat Management in the Southeastern United States." Anthrozoos: A Multidisciplinary Journal of The Interactions of People & Animals Anthroz Jour Inter Peo Ani 25.3 (2012): 337-51. Web. 7 Oct. 2015. Nutter, Felicia B. "Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases." Diss. North Carolina State U, 2005. NCSU Libraries. North Carolina State University, 1 Mar. 2006. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. Scarlett, Janet M. Letter to Kathleen A. Marchione. 20 Apr. 2015. New York State Animal Protection Federation. New York State Animal Protection Federation. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. Scott, Karen C., Julie K. Levy, Shawn P. Gorman, and Susan M. Newell Neidhart. "Body Condition of Feral Cats and the Effect of Neutering." Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 5.3 (2002): 203-13. UF Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program. University of Florida Health, Aug. 2012. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. "The Vacuum Effect: Why Catch and Kill Doesn’t Work." Alley Cat Allies. Alley Cat Allies, Feb. 2011. Web. 07 Sept. 2015. Williams, Geoff. "US Is Overrun with More than 50 Million Feral Cats." Aljazeera America. Al Jazeera America, LLC, 6 Nov. 2013. Web. 14 Sept. 2015.