Albert Camus`s Myth of Sisyphus - PLATO: Philosophy Learning and

advertisement

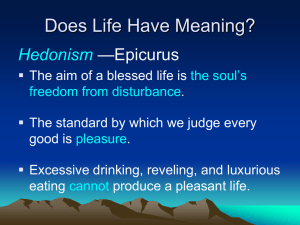

The Myth of Sisyphus─Albert Camus by Richard Vogel and Bernard Sell Albert Camus (1913-1960) was a French-Algerian writer closely linked by some to existentialism and by others to absurdism although Camus himself detested both of these labels (and labels in general). Perhaps best known for novels such as The Stranger, The Plague, and The Fall, he explored existential and absurdist themes in his nonfiction writings as well. The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), for example, contains both existentialist and absurdist strands. In exploring the myth of Sisyphus (Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1955, 1983. ISBN #0-679-73733-6), first read pp. 119-123, which summarize the classical myth itself. The following questions are intended to examine the myth that provides the foundation for Camus’ essay, and then to explore the connection Camus sees between the story of Sisyphus and the position of man in a seemingly absurd, hostile and indifferent universe. Inasmuch as much of the essay refers to the beliefs of other philosophers such as Husserl, Jaspers and Kierkegaard, whose ideas may be unfamiliar to students first encountering this essay, an attempt has been made to focus in on key pages that may help establish clarity and coherence. The essay is particularly useful in understanding the situation and attitude of Mersault in The Stranger. From “The Myth of Sisyphus:” (read pages 119-123) 1. Though Camus proffers various reasons as to why the mythical Sisyphus was condemned to such an arduous and futile fate, and imaginatively depicts Sisyphus’ strenuous effort to push the boulder up the hill, he says that it is the moment just after the stone rolls back down the incline that interests him the most, labeling it his “hour of consciousness,” a time when he is “superior to his fate” (121). What is ironic about Camus language here and how does he explain this unusual take on Sisyphus’ reaction to this futility? 2. Camus says “There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night” (123), implying perhaps that it is crucial to accept an irrational, even absurd suffering as part of the human experience. To this he adds that Sisyphus “teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks,” ultimately concluding that “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” (123). In light of the arduous fate to which he has been condemned, how does one explain this incongruous perspective? How can Sisyphus possibly be happy, given his onerous circumstance? How can one rejoice in torment? Camus also uses the imperative, saying “We must imagine [Sisyphus] happy?” Why this word “must?” What implications does this suggest for human beings? From “Absurdity and Suicide:” (Read pages 3-10) 3. Camus opens his essay with the bold claim that “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide” (3), saying that the taking of one’s own life is “confessing that life is too much for you or that you do not understand it” (5). Camus further states that “in a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lights, man feels an alien, a stranger” and that his “exile is without remedy since he is deprived of the memory of a lost home or the hope of a promised land” (6). Though Camus ultimately rejects suicide as a rational action, he tries to understand why a human might even consider such a drastic action. How has the story of Sisyphus triggered this thought? To what might Camus be referring in the words and phrases of the final citation from page 5? What might constitute the “lost home” and the “promised land” and how does their absence impact humans in a negative fashion? From “Absurd Walls:” (Read pages 12-22, 27-28) 4. Camus suggests that man seeks clarity in the universe, that if he realized “that the universe like him can love and suffer, he would be reconciled” (17), only to state that man is denied this clarity and instead feels alienated. He further observes that “At this point of his effort man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within him his longing for happiness and for rationality. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world” (28). What does he mean when he says “In this unintelligible and limited universe, man’s fate henceforth assumes its meaning” (21)? What are the ways in which this man─universe confrontation may be mediated? Camus suggests we not be overwhelmed by this realization that the world inherently will not meet our needs and desires. How is this possible? From “Philosophical Suicide:” (Read pages 28-32; bottom 49-50) 5. In this section of his essay, Camus implies that some existential philosophers attempt to rationalize the irrational, claiming that “in a closed universe limited to the human, they deify what crushes them and find reason to hope in what impoverishes them” (32) and suggesting that the absurd is replaced by God. What, precisely, is the Absurd? Consider the following passage in your response: “…I must admit that that struggle implies a total absence of hope (which has nothing to do with despair), a continual rejection (which must not be confused with renunciation), and a conscious dissatisfaction (which must not be compared to immature unrest). Everything that destroys, conjures away, or exorcises these requirements (and, to begin with consent which overthrows divorce), ruins the absurd and devaluates the attitude that may then be proposed” (31). What position would Camus take on these philosophers’ perspective? Why does he insist on page 50 that he “is not interested in philosophical suicide, but rather in plain suicide”? What is the difference? Why does Camus see philosophical suicide as undesirable, and can one possibly avoid it? From “Absurd Freedom:” (Read pages 51-65) 6. Camus avers that “In its way, suicide settles the absurd” (54), saying that “Before encountering the absurd, the everyday man lives with aims, a concern for the future or for justification…He weighs his chances, he counts on ‘someday,’ his retirement or the labor of his sons. He still thinks that something in his life can be directed…” (57). How does man’s encounter with the absurd change his perspective? Why does Camus ultimately opt for defiance over self-sacrifice? How is this stance noble, even heroic?