File - Nicale Yarbrough

advertisement

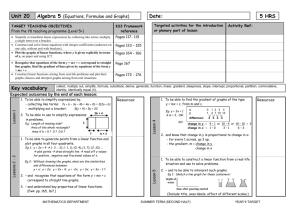

Nicale Yarbrough AT 2501 Case Study Cuboid Syndrome Abstract: Objective: To introduce a case to the athletic trainer of a 21-year-old female with overuse cuboid syndrome as a result in participating in a half marathon. Background: The patient was in a half marathon when she began to have pain in her fourth and fifth metatarsal 2 weeks after participating. Evaluation showed no signs of weakness or fracture. Referred to physician where x-rays showed no abnormality. Differential Diagnosis: Cuboid fracture, stress fracture, peroneal subluxation, Jones fracture. Treatment: After being seen by the physician and fracture was ruled out by an x-ray of the foot. The patient was treated with cuboid whip done by the physician along with a specific taping technique. The patient was cleared to return to full activity. Uniqueness: Not often do you see overuse cuboid syndrome as such in this patient most of the time it is cause by a lateral ankle sprain. This is something that is not seen very often in athletic training and can be manageable by the patient if diagnosed correctly. Conclusion: The athletic trainer needs to be aware of the repercussions of a lateral ankle sprain or just overuse injuries to the foot. If an athletic trainer catches cuboid syndrome doing a cuboid whip/cuboid squeeze, taping techniques and rehabilitation, can easily treat it. All the while the patient is still able to play or participate in activities with pain being your constant guide. Key Words: Cuboid whip, subluxation, articulation. Introduction: Cuboid pathology is often overlooked in an examination; yet such an injury can cause a lot of issues as far as walking and normal daily activities. Because it is often misdiagnosed and mistreated there is not much knowledge or insight on how to go about treating it. Cuboid syndrome is defined as a minor disruption or subluxation of the structural congruity of the calcaneocuboid portion of the midtarsal joint. The disruption of the cuboids’ position irritates the surrounding joint capsule, ligaments, and peroneus longus tendon.1 This report is to give insight on an active 21-year-old woman case to help the athletic trainer better evaluate and treat this condition accordingly. Case Report: An active 21-year-old female had complained of left foot pain after completing a half marathon she had participated in two weeks prior. Her pain was particularly over the anterior lateral portion of the foot on the fourth and fifth metatarsals. She stated that she had pain with every step that she took, and her gait was starting to compensate for the pain. The patient had a physical therapist that she worked for examine her foot. She informed the clinician that she had participated in a half marathon two weeks prior to examination but before then had not had any pain. She also stated that she had to walk at mile nine because her foot pain hurt so bad to continue running. Patient also competes in clogging and has for the last 17 years; her training had not changed in that aspect. Upon examination the patient had tenderness to palpation on the fourth and fifth metacarpal and none to the first, second, or third metacarpal. No tenderness to the cuneiforms first through third, navicular, or lateral malleolus. There was some pain when palpating the cuboid but not as much as the metatarsals. No pain to the proximal interphalangel joint of any of the phalanges. Manual muscle testing showed no noticeable deficiencies bilaterally. A score of 4+/5 on the left foot for extensor digitorium longus tendons patient complains of pain especially over the fourth and fifth metatarsal. Long bone compression, and load test were negative on the 4th and 5th metatarsal. The tuning fork excited mild discomfort. The patient was then referred to the doctors for x-rays and diagnosis. Course of Treatment: The x-rays were negative noticing no abnormalities. The doctor then pulled the toes down to curve over his finger after comparing bilaterally he noticed that the forth and fifth distal metatarsal heads had looked to have dropped lower then the others on the left foot. They were not as prominent when compared to the right foot. The doctor then diagnosed the patient with cuboid syndrome. He then had the patient stand up holding on to the examination table and then had the patient bend her knee to 90°. He then took hold of her foot and then he found the cuboid and rolled it around in his hand then told the patient to relax as he moved the cuboid between his thumbs and held onto the forefoot with the rest of his hand he then forcefully downwardly whipped the foot. He did this twice and called it the “cuboid whip”. After he had done this he had the patient walk up and down the hall to see if there was a difference in pain with walking. The patient stated that she no longer had any pain. He told the patient to tape her foot. The tap wrapped around the forefoot starting on the bottom of the foot and when the patient reached the cuboid the patient was instructed to pull up and in and do this tapping two to three times around the foot, patient was instructed to use this tape job when engaging in physical activity. If patient started to feel the same symptoms then they are to get a tennis ball place it on the lateral aspect where the cuboid is located and put all her weight on to the tennis ball then to bounce two to three times putting all her weight into it and do it abruptly and hard. The doctor then informed the patient that this is often seen in ballet dancers. Male ballet dancers have an occurrence of cuboid syndrome from jumping and the foot continuously abruptly pronating. Where as for female ballet dancers it was an overuse syndrome, resulting from multiple micro traumas to the ligamentous structures during maneuvers requiring maximal flexibility2. The doctor told the patient that she was able to participate in all activities and that the taping was to be done for four weeks then she could slowly taper off as long as the pain did not return. Discussion: This diagnosis is also known as subluxed cuboid, locked cuboid, dropped cuboid, cuboid fault syndrome, lateral plantar neuritis, and peroneal cuboid syndrome3. Radiologic evaluation or other imaging studies have been reported to have little value for the diagnosis of cuboid syndrome4. But after ruling out with an x-ray this could have been very easily looked over after realizing there was no present or obvious diagnosis of what was originally thought of which was a stress fracture. There are many other injuries that this case could have been that have similar signs and symptoms presenting on the lateral aspect of the foot. These similar injuries include: Jones fracture, fracture of the anterior calcaneal process, tarsal coalition, peroneal and extensor digitorum brevis tendonitis, subluxing peroneal tendons, sinus tarsi syndrome, lateral plantar nerve entrapment, Lisfranc injuries, stress fractures of the cuboid, meniscoid of the ankle, and malalignment of the lateral ankle and subtalar joints5,6. But with having a doctor that was very aware and had seen previous patients that had presented with similar signs and symptoms he was able to diagnosis correctly and the patient was able to leave pain free. Also, the doctor had stated that he had been recently to conference that had specifically reviewed this diagnosis of cuboid syndrome. With this knowledge we were able to come up with a plan that would treat the patient accordingly. Although the patient was not instructed to do any therapeutic exercise, literature states that therapeutic exercises should focus on strengthening the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the foot, and proprioception through the use of neuromuscular control exercise4. Without the correct diagnosis and protocol the cuboid would continue to sublux and this could cause the patient a lot of pain and frustration. Conclusion: With the increase awareness of cuboid syndrome this is becoming something that is going to be less missed and better treated. When doing an evaluation some things tools that would better diagnose cuboid syndrome were done in this particular case study and some that the literature found useful to use in an examination. There are no actually special test to diagnose cuboid syndrome so you are having to rely heavily on a history, observation, and palpation. A cuboid subluxation should create hypermobility; however, because pain is the predominant characteristic, it is very difficult to perform valid and reliable mobility testing7. Upon examination the gait of the patient will be typically antalgic, with most pain present during push off2. During push off, the calf muscles shorten to actively plantar flex the foot to generate an explosive push off which is where they will have the most pain8. What seemed to help the doctor in coming up with a diagnosis of cuboid syndrome is that of pulling the toes down to look at metatarsal level. After the cuboid manipulation or also known as the cuboid whip the patient may report complete cessation of symptoms9. Which in this case is exactly what happened. There are other ways of accomplishing this manipulation in a different way, which is called the cuboid squeeze. The clinician gradually places the foot and ankle into maximal plantar flexion, as soft tissues relax the cuboid is squeezed with the thumbs. It has been documented that the cuboid squeeze is better suited for cuboid syndrome, which has occurred secondary to an overuse syndrome2. Something that was not recommended to this patient but is mentioned in the review is a cuboid pad. The cuboid pad should be constructed using a piece of 1/8 to ¼ inch felt approximately 1½ inches wide and measuring the distance from the calcaneocuboid articulation to the cuboid-5th metatarsal articulation to determine the length, normally around 2-3 inches10. The pad is placed on the plantar aspect of the cuboid, making sure that it does not extend past the styloid process of the fifth metatarsal, and held in place by a low dye taping technique5. This is an option along with the other treatments practiced in this particular case study. Common mechanisms of this injury are plantar flexion and inversion ankle sprains or overuse syndrome11. When dealing with athletes who have pain post lateral sprain or an overuse injury with signs and symptoms over the later aspect of the foot with tenderness over the cuboid you need to be aware of the possibility of your patient having cuboid syndrome, which needs the evaluation of a physician. References 1. Blakeslee, T. J., & Morris, J. L. Cuboid syndrome and the significance of midtarsal joint stability. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 1987; 77(12), 638-642. 2. Marshall, P., & Hamilton, W. G. Cuboid subluxation in ballet dancers. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 1992; 20(2), 169-175 3. McDonough, M. W., & Ganley, J. V. Dislocation of the cuboid. Journal of the American Podiatry Association, 1973; 63(7), 317-318. 4. Mooney M, Maffey-Ward L. Cuboid plantar and dorsal subluxations: assessment and treatment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994; 20:220-226. 5. Caselli, M., & Pantelaras, N.How to treat cuboid syndrome in the athlete. Podiatry Today, 2004; 17(10), 76-80. 6. Dewar, F.P and Evans D.C. Occult fracture- subluxation of the midtarsal joint. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 1986; 50B, 386. 7. Jason Jennings, D. P. T. Treatment of cuboid syndrome secondary to lateral ankle sprains: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2005; 35(7). 8. Rodgers, M. M. Dynamic biomechanics of the normal foot and ankle during walking and running. Physical Therapy, 1998; 68(12), 1822-1830. 9. Newell, S.G. and Woodle, A. Cuboid Syndrome. Physician and Sports Medicine 1981; 9, 71-76. 10. White, S.C. Padding and taping techniques. Clinical Biomechanics of the Lower Extremities. 1996; Mosby, St. Louis, MO. 11. Khan, K., Brown, J., Way, S., Vass, N., Crichton, K., Alexander, R., ... & Wark, J. Overuse injuries in classical ballet. Sports Medicine, 1995; 19(5), 341-357. 12. Gille, W. The small-angle scattering correlation function of the cuboid. Journal of applied crystallography, 1999; 32(6), 1100-1104. 13. Gough, D. T., Broderick, D. F., Januzik, S. J., & Cusack, T. J. Dislocation of the cuboid bone without fracture. Annals of emergency medicine, 1988; 17(10), 1095-1097. 14. Huson, A. Biomechanics of the tarsal mechanism. A key to the function of the normal human foot. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 2000; 90(1), 12-17. 15. Patterson, S. M. Cuboid syndrome: a review of the literature. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 2006; 5, 597-606.