A New Model of Student Teaching: Co

advertisement

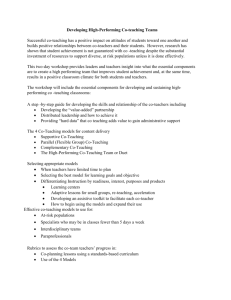

Co-Teaching: A Win-Win for Public School Classrooms and Teacher Preparation Programs Christina M. Tschida, Judith J. Smith, Elizabeth A Fogarty, Kristen Cuthrell, Joy Stapleton Christina Tschida, Assistant Professor for the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, East Carolina University, College of Education, MailStop 504, Speight Building, Greenville, NC 27858, 252-328-4945 tschidac@ecu.edu Dr. Tschida’s primary research areas are teacher education, online teaching and learning, culturally responsive teaching, and social studies instruction. She has presented at AERA, NCSS, CUFA, SITE, and NAME. Judith J. Smith, Assistant Professor for the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, East Carolina University, College of Education, MailStop 504, Speight Building, Greenville, NC 27858, 252-737-2486, smithjud@ecu.edu Dr. Smith’s primary research areas are teacher education, language/literacy, and educational technology/21 century literacies. Dr. Smith has published st articles in Studying Teacher Education, Journal of Information Technology Education, Insight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, Current Issues in Education, Computers in the Schools, and Education Research and Perspectives Journal. She has presented nationally at AACTE, ELEARN, SITE, AERA, LRA, and AACE. Elizabeth Fogarty, Interim Associate Chairperson and Associate Professor for the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, East Carolina University, College of Education, MailStop 504, Speight Building, Greenville, NC 27858, 252-328-4945 fogartye@ecu.edu Dr. Fogarty’s research centers on teacher effectiveness including teachers’ ability to differentiate and meet the needs of gifted learners. Dr. Fogarty advocates for gifted children and their teachers through several professional organizations. Kristen Cuthrell, Interim Associate Chairperson and Associate Professor for the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, East Carolina University, College of Education, MailStop 504, Speight Building, Greenville, NC 27858, 252-328-5748 cuthrellma@ecu.edu Dr. Cuthrell’s primary research areas are teacher education, curriculum revision issues, and assessment. Dr. Cuthrell has published articles in Childhood Education, The Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, The Clearing House, Computers in the Schools, The Social Studies, Preventing School Failure, and Florida Reading Quarterly. She has presented nationally at NCSS, AACTE, ELEARN, SITE, ATE, AERA, and ASCD. Joy Stapleton, Associate Professor for the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, East Carolina University, College of Education, MailStop 504, Speight Building, Greenville, NC 27858, 252-328-6649, stapletonj@ecu.edu Dr. Stapleton’s primary research areas are teacher education, curriculum revision issues, and assessment. Dr. Stapleton has published articles in National Social Science Journal, MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, Tech Trends, Preventing School Failure, E Journal of Teaching and Learning in Diverse Settings, Childhood Education, Reading Research and Instruction, Journal of Interactive Learning and Research. She has presented nationally at NCSS, AACTE, ELEARN, SITE, ATE, and ASCD. Abstract While Co-Teaching in student teaching has proved successful with a ratio of one to one, that is, one student teacher and one clinical teacher working together, this study investigates a new model of student teaching: Co-Teaching two to one where two student teachers work in collaboration with one clinical teacher. Researchers argue that the new model (2:1) is as good as, if not, better than the traditional model of student teaching and enhances the student teaching experience. Introduction Surprisingly, the student teaching experience has been significantly unchanged since the 1920s (Guyton & McIntyre, 1990). According to the Council of Chief State School Officers (2012) clinically-based preparation programs must provide relevant, well-planned experiences to prepare teacher candidates. More important, the clinical experience should be placed at the center of teacher preparation in order to inspire preservice teachers as they begin their teaching career. Large teacher preparation programs face significant challenges in placing clinical interns in the field because schools and clinical teachers are unwilling to host them (Goodlad, 1994; Ladson-Billings, 2001; Sinclair, Dawson, & Thistleton- Martin, 2006; Zeichner, 2002). Because the need is so great, oftentimes, clinical teachers who agree to host a clinical intern are unqualified to model best teaching practices for the novice intern (Grimmett & Ratzlaff, 1986; Lewis, 1990). Hence, during this impressionable time, clinical interns may experience unrealistic expectations (Sparks & Brodeur, 1987) and receive little valuable feedback from the clinical teacher (Morehead & Waters, 1987). In their report for transforming educator preparation and entry into the profession, The Council of Chief State Schools Officers (2012), advocated for a screening process for identifying clinical teachers as well as providing training to demonstrate effective instructional practices and to positively impact student achievement. To overcome the challenges of placing large numbers of clinical interns and to strengthen the teacher preparation program, the college of education at a large regional university is engaged in a new model of student teaching: Co-Teaching. After completing Co-Teaching training, clinical teachers and clinical interns plan together, deliver instruction, assess students’ progress, as well as, share students and the organization and physical space of the classroom. The College of Education is experimenting with different Co-Teaching models as alternatives to traditional student teaching: a two-to-one (2:1) model which involves two clinical interns and one master clinical teacher, a one-toone (1:1) model involving one clinical intern and one master clinical teacher, and a two- to-two (2:2) model where two clinical interns and two master clinical teachers work together. Co-Teaching should reduce significantly the number of internship placements; thereby, enabling the Office of Teacher Education to be more selective in choosing clinical teachers. Perspectives/Theoretical Framework Co-Teaching is defined as two or more teachers [intern(s) and clinical teacher] working together with groups of students...sharing the planning, organization, delivery and assessment of instruction, as well as the physical space. Co-Teaching is an attitude of sharing responsibility for the students and the classroom. The “Co” in Co-Teaching stands for “collaborative” which means that clinical intern and master clinical teacher are co-planning, co-teaching, co-assessing, and co-reflecting on practice. Carambo & Stickney (2009) found that co-teaching is better than the traditional model for student internships because it takes away the sharp dichotomy between the beginning teacher candidate and the experienced classroom teacher. Ruys, Van Keer & Aelterman (2010) report that both teacher educators believe that collaborative learning has value and that implementation of collaborative learning will yield positive results such as high student achievement. The Co-Teaching initiative is patterned after Marilyn Friend’s research which includes 7 strategies for Co-Teaching (Cook & Friend, 1995). These strategies are: one teacher, one observe; one teach, one assist; station teaching; parallel teaching; supplemental teaching; alternative or differentiated teaching; and team teaching. More recently, the Academy for Co-Teaching and Collaboration at St. Cloud State University (Bacharach, Heck, & Dahlberg, 2008) applied co-teaching in the student teaching experience enabling two professionally prepared adults to collaborate in the classroom and expanding Co-Teaching to two teachers (clinical teacher and clinical intern) working together with groups of students – sharing the planning, organization, delivery and assessment of instruction, as well as the physical space during student teaching. Both teachers are actively involved and engaged in all aspects of instruction. Ruys, Van Keer & Aelterman (2010) report that clinical teachers and clinical interns believe that collaborative learning has value and that implementation of collaborative learning will yield positive results for k-12 students as well as clinical interns. What are experts saying about Co-Teaching? Carefully designed student teaching experiences, specifically Co-Teaching, can effectively prepare clinical interns while impacting student achievement. Co-Teaching initially began as a collaboration between general education and special education in response to PL94-142 (IDEA) legislation to support students with disabilities in general education classrooms (Boucka, 2007; Cook & Friend, 1995; Hang & Rabren, 2009; Vaughn, Schumm, Arguelle, 1997). Faculty at St. Cloud State University applied this CoTeaching method/principle to the student teaching experience allowing clinical teachers to collaborate with clinical interns in the classroom. Cumulative student achievement data gathered from 2003-2007 at St. Cloud State University found statistically significant gains in reading and math proficiency when 35,000 P-12 students were compared in CoTaught and Not Co-Taught student teaching settings. Co-Teaching strategies applied to student teaching have been used successfully at all grade levels and in every content area, from preschool to senior high. Clinical interns and their clinical teachers have effectively incorporated co-teaching into the classroom (Bacharach, Heck & Dahlberg, 2010). St. Cloud’s Co-Teaching model of student teaching has been recognized as a promising practice by the NCATE Blue Ribbon panel on clinical practice (2010). In addition, this innovative initiative received the 2008 American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education (AACTE) Best Practice Award for Research in Teacher Education, and the 2007 American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) Christa McAuliffe Award for Excellence in Teacher Preparation. Rationale for adopting the Co-Teaching Model The need to change student teaching to the Co-Teaching model is rooted in several public education initiatives. The Professional Teaching Standards now evaluates teachers on five general standards and a sixth standard tied directly to student achievement. In the past, classroom teachers would give their class over to the clinical intern for a full three weeks, which is no longer desirable. This new model of CoTeaching has both teachers continuously working with all students. Co-Teachers are always thinking, they are both teaching; giving clinical interns more engaged teaching experience than traditional models. Using Marilyn Friend’s and St. Cloud’s Co-Teaching research, we are experimenting with two clinical interns in a single classroom with one master clinical teacher and two clinical interns with two master clinical teachers, in addition to, the more common model of one clinical intern and one master clinical teacher in a single classroom. Co-Teaching has tremendous potential for raising student achievement, especially for diverse learners as noted in the following participants’ comments: “I think this is a great model that will improve beginning teachers’ confidence, knowledge, as well as positively impacting student learning.” Another remarked, “We do not have the behavior issues…wait time is gone because, with 3 teachers, questions can be addressed immediately. Students are getting what they need right away.” A middle school student summed up Co-Teaching by saying, “Double the teachers, and double the learning!” Researching different models of Co-Teaching This large university College of Education researched effective teacher preparation through models of Co-Teaching focused on the following objectives: 1. exploring the nature of co-teaching that is naturally occurring during student teaching 2. examining experience of clinical interns engaged in 1:1, 2:1, and 2:2 models of CoTeaching 3. determining differences in teaching ability of clinical interns participating in CoTeaching and those not participating in Co-Teaching 4. exploring effects of collaboration on clinical interns’ dispositions 5. examining planning in Co-Taught classrooms and determining whether the planning differs from the traditional internship classrooms Qualitative and quantitative methods were used to gather data from two cohorts of 162 participants randomly assigned to either Co-Teaching or non Co-Teaching elementary classroom placements from 2012-2013. Clinical interns and clinical teachers were given five hours of training on the Co-Teaching model. Data sources included CoTeaching strategy usage records, surveys, collaboration self assessments, intern collaboration assessments, focus group transcriptions, transcriptions from recorded planning sessions, Teaching Portfolio Assessment (edTPA) results, progress reports, walkthrough observations, and teaching evaluations. Preliminary findings from analysis of interns’ edTPA scores show positive trends for those participating in Co-Teaching. Interns that co-taught attained higher mean scores on 11 of the 15 edTPA rubrics than those in the non-Co-Teaching classrooms. Co-Teaching interns performed significantly higher in “subject-specific pedagogy” and “using assessment to inform instruction” than non-Co-Teaching interns. Data also indicate that interns in the Co-Teaching treatment group felt that they were better able to differentiate than their non-Co-Teaching peers. What are the implications of Co-Teaching for clinical preparation? Current Co-Teaching research is being used to support engaging, collaborative partnerships between the university and local public schools lowering the number of classrooms needed and allowing for a more careful selection of effective clinical teachers. Clinically-based teacher education programs are using data analysis of the CoTeaching experiences to guide decision making for reforming clinical experience and initiating successful and effective practice. In addition, Co-Teaching has tremendous potential for raising student achievement, especially for diverse learners. Co-Teaching is a win-win for public school classrooms and pre-service teacher preparation programs. References Bacharach, N., Heck, T., & Dahlberg, K. (2010). Changing the Face of Student Teaching Through Coteaching. Action in Teacher Education 32(1), 3-14. Bacharach, N., Heck, T., & Dahlberg, K. (2008). What makes co-teaching work? Identifying the Essential Elements. College Teaching Methods & Styles Journal, 4(3), 43-47. Boucka, E. C. (2007). Co-Teaching…not just a textbook term: implications for practice. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 51(2), 46-51. Carambo, C., & Stickney, C. T. (2009). Coteaching praxis and professional service: Facilitating the transition of beliefs and practices. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 4(2), 433-441. Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-Teaching: Guidelines for creating effective Practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1-17. Council of Chief State School Officers. (2012). Our responsibility, our promise: Transforming educator preparation and entry into the profession. Washington, DC: Author. Goodlad, (1994). The national network for educational renewal. Phi Delta Kappan, 75(8), 632-639. Grimmett, P., & Ratzlaff, H., (1986). Expectations for the cooperating teacher role. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(6), p 41-50. Guyton, E., & McIntyre, D. (1990). Student teaching and school experiences. In W. Houston (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp.514-534). New York: Macmillan Hang, Q. & Rabren, K. (2009). An examination of co-teaching perspectives and efficacy indicators. Remedial and Special Education, 30(5), 259-268. Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan: The journey of new teacher in Diverse classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Lewis, M. (1990). AACTE RATE study finds enrollment increase. AACTE Briefs 11(3), 1,6. Morehead, M., & Waters, S. (1987). Enhancing collegiality: A model for training Cooperating teachers. The Teacher Educator, 23(2), 28-31. National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2010). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: Report of the blue ribbon panel on clinical preparation and partnerships for improved student learning. Washington, DC: Author. Ruys, I., Van Keer, H., & Aelterman, A. (2010) Collaborative learning in pre-service Teacher education: An exploratory study on related conceptions, self-efficacy And implementation. Educational Studies, 36(5), 537-553. Sinclair, C., Dawson, M., & Thistleton- Martin, J. (2006). Motivations and profiles of Cooperating teachers: Who volunteers and why? Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 263-279. Sparks, S., & Brodeur, D. (1987). Orientation and compensation for cooperating Teachers. Teacher Educator, 23(1), 2-12. Vaughn, S., Schumm, J., & Arguelle, M. (1997). The ABCDEs of co-teaching. Teaching Exceptional Children, 30(2), 4-10. Zeichner, K. (2002). Beyond traditional structures of student teaching. Teacher Education Quarterly, 29(2), 64.