309-1158-1-ED - Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry

advertisement

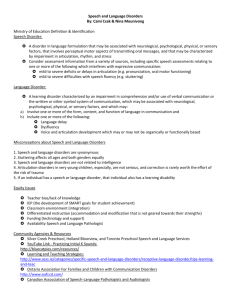

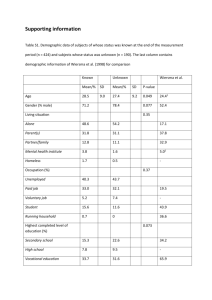

To, The Editor Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry Subject: submission of edited manuscript Dear Sir/ Madam, We are submitted the answers to the queries of the reviewers of our manuscript “Comorbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder in an Indian patient population”. We have also made the necessary changes suggested by the reviewers. Thanking you. Yours’ sincerely, Corresponding contributor: Dr. Chetali V. Dhuri Department of Psychiatry, Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai 400012, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: chetali.dhuri@gmail.com 1 ANSWERS TO QUERIES: 1. Specify whether subjects with alcohol use not amounting to disorder excluded. Answer: Subjects with alcohol use not amounting to disorder were not excluded. 2. Any separate scale other than MINI used to diagnose nicotine dependence? Answer: Only MINI was used to diagnose nicotine dependence. 3. Any of Suicidality scales used or not? Answer: Separate scales of suicidality were not used, assessment for suicidality was done using MINI. 4. Any of the subjects diagnosed with OCD with poor insight? Answer: The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI) english version 6.0.0 DSM- IV used to diagnose axis I comorbidity by us does not have questions to distinguish OCD with good insight from poor insight. Hence, it would be difficult to comment on the number of subjects with poor insight. 5. The low prevalence of these disorders with OCD as evident in this and other Indian studies may be related to socio cultural differences, as prevalence of both bipolar disorder and eating disorders even among general population is high in industrialized, affluent countries linking the disorders to affluent society. Please quote the reference for this statement. Or else statement should be modified. 2 Answer: The statement is modified as- The low prevalence of these disorders with OCD as evident in this and other Indian studies may be related to socio cultural differences, as prevalence of both bipolar disorder and eating disorders even among general population is high in industrialized, affluent countries linking the disorders to high socio economic status. The following references have been added in support of the statement. i. Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Marazziti D, Raffaelli S, Rossi G, Cassano GB. Social class and mood disorders: clinical features. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993; 28:56-9. ii. Okasha A, Kamel M, Sadek A, et al. Psychiatric morbidity among university students in Egypt. British Journal of Psychiatry 1977; 131: 149154. iii. Verdoux H, Bourgeois M. Social class in unipolar and bipolar probands and relatives. J Affect Disord. 1995; 33: 181-7. 6. Our subjects also reported high level of fear, anxiety about the effect of alcohol & other substances on their general health and OCD particularly thus avoiding it. Whether any particular scale was used? Answer: No particular scale was used. The above statement is made as most of our patients reported worry about effect of alcohol and other addictive drugs and quoted it as the reason to avoid it. 7. The references have been edited to follow the uniform reference style according to author guidelines of the journal. 3 Abstract: Introduction: Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is associated with substantial comorbidity, not only with anxiety and mood disorders but also with psychotic and substance use disorders. The Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study, reported co-morbid psychiatric illness in two third of its OCD subjects. The Indian research in this aspect is sparse. Methods: The objective was to assess the prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidities in patients with OCD in an Indian setting. Fifty patients meeting the DSM-IV TR diagnostic criteria for OCD were selected for the study. The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI) english version 6.0.0 DSM- IV, a brief structured interview for the major axis I psychiatric disorders was used to measure psychiatric co-morbidity. Results: Sixty four percent of the sample was male and the mean age was 30.62 years. One or more co-morbid psychiatric disorder was seen in 96% of the sample. The most common psychiatric disorder associated was major depressive disorder (90%) followed by suicidality (62%), anxiety disorders (50%) and psychotic disorder (22%). Nine patients (18%) had comorbid nicotine dependence. Conclusion: The prevalence of co-morbid major depression, anxiety disorders and suicidal risk in our sample is similar to the western data. Certain co-morbities like bipolar disorder, eating disorder, alcohol and non alcohol substance use disorders other than nicotine were absent in this sample, a finding distinct in our setting in comparsion to western studies. Keywords: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Co-morbidity, Major Depressive Disorder, Psychosis 4 Introduction: Psychiatric co-morbidity may be defined as the co-occurrence of two or more psychiatric disorders in any combinations in the same person. Co-morbid psychiatric conditions influence the treatment response, prognosis and also influence help seeking behavior 1. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is associated with substantial co-morbidity, not only with anxiety and mood disorders but also with psychotic and substance use disorders. In the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study, two thirds of those with OCD had a co-morbid psychiatric illness commonly major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorders 2. For mood disorders, prevalence co-morbid rates range from 12 to 85 % 3-5 and for anxiety disorders 24 to 70 percent 2, 4. The ECA study also reported other concurrent co-morbidities like problem drinking( 24%), social phobia(11-23%), generalized anxiety disorder (18-20%), simple phobia (7-21%), panic disorder (6-12%) ,eating disorder (8-15%), amongst the OCD patients. The available data suggests that nearly 15% of OCD patients have bipolar disorder; mainly hypomania 6, 7; also psychotic symptoms are reported in the range of 6% to 32% in OCD patients 8-10. However, there is considerable variability amongst these studies in the reported prevalence rates of comorbid disorders. There are few studies from India investigating the prevalence of comorbidities in OCD. Our study is an attempt to study these co-morbidities in comparison with the western data. Materials and Methods: 5 Study design and sample: A descriptive study of out-patients at a tertiary care center in Mumbai, India was conducted. 50 OCD subjects above 18yrs satisfying the DSM-IV TR diagnostic criteria were consecutively included in the study. Individuals with history of or concurrent neurological or medical disorder or psychosis as primary diagnosis were excluded. The group consisted of 18 women and 32 men. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the institution. Informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study. Those who agreed to participate were engaged in a detailed clinical interview by the authors using a semi-structured questionnaire to study the sociodemographic profile and the psychiatric co-morbidities. Tools: The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI) english version 6.0.0 DSM- IV, a brief structured interview for the major axis I psychiatric disorders was used to measure psychiatric co-morbidity in the OCD subjects. It is divided into 16 modules each corresponding to a diagnostic category namely, major depressive episode, manic /hypomanic episode/ bipolar I/II disorder, panic disorder agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive‐compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol dependence/ abuse, substance dependence/abuse (non‐alcohol), psychotic disorders, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, generalized anxiety disorder, medical/ organic/ drug cause and antisocial personality disorder. Statistical analysis: The data was entered using MS-Excel-2007 and analysed using SPSS-16 software. Proportions were calculated to identify the rates of comorbidity. 6 Results: The sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 30.62 years with their ages between the ranges of 18-59 years. Males were more in number than females (64 vs 36%). Most patients were Hindus (66%). More than half of the sample was higher secondary or more educated (56%) and employed (52%). The age of onset of OCD was 21.88 years for males and 25.89 years for females. The mean duration of illness for males and females was 6.56 years and 8.72 years respectively. The co-morbid psychiatric diagnosis is given in table 2. Forty eight patients had one or more co-morbid psychiatric diagnosis (96%). The most frequent co-morbidity was the MDD (90%), with 70% patients satisfying criteria for current MDD. 62% also reported suicidal ideation. Co-morbid anxiety disorder reported were, panic disorder current (12%), panic disorder lifetime(14%), agoraphobia(14%) and social phobia (10%). 28% of the patients also met criteria for psychotic disorder. No subject in our study satisfied criteria for manic episode/ hypomanic episode/ bipolar I disorder/ bipolar II disorder/ bipolar disorder NOS, post traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and eating disorder. Nine patients (18%) had comorbid nicotine dependence. Discussion: In this study the prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity was high (96%), MDD (90%) was the most common co-morbidity followed by anxiety disorders (50%). These findings are similar to the high prevalence of co-morbid mood and anxiety disorders as reported 7 in the ECA and other western studies2-5. Rasmussen reported over the course of their lifetime, up to 80% OCD patients may experience depressive episodes11. This is at variance with the finding of the only Indian study by Bhattacharyya et al (2005) where prevalence of co-morbidity was low, with depression in 17%, dysthymia in 6% and in 7 % any anxiety disorder12. A significant proportion of the subjects in our sample also reported suicidal ideation (62%). Co-morbid MDD was the risk factor for suicidality, as all the subjects with suicidal ideation satisfied criteria for MDD current or past. In an Indian study of OCD patients, 59% reported worst ever life time suicidal ideation, 28% had current suicidal ideation and 27% had history of suicidal attempt 13. The relation between depression and OCD is complex, with some believing depression to be complication of OCD9, whilst others believe that OCD and depression are two separate entities which often coexist14. Studies by Perugi et al and Tukel et al have reported association between MDD in OCD with older age, severity and chronicity of OCS, number of hospitalizations, greater co-morbidity with generalized anxiety disorder, simple phobias and caffeine abuse, higher number of suicide attempts, and disability15, 16. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors are an effective treatment for both the conditions , however severe MDD in OCD is also associated with poor response to behavioral therapy17. 28% of our OCD subjects also met criteria for psychotic disorder. Psychosis can emerge in OCD when resistance to obsessions is abandoned and insight is lost or when there is subsequent onset of paranoid ideas 18, 19. Psychosis can also be secondary to disturbed affect i.e. guilty preoccupation may get transformed into a delusional conviction that one is being subject to persecution18. Also, more than two third (78.5%) 8 of our subjects with psychotic disorder also had co-morbid depressive disorder. Thus, this strong association between depressive features and psychotic features in OCD is of interest from phenomenological point of view i.e. whether psychotic features are part of OCD or are due to coexisting depression. Also, treatment of co-morbid OCD and psychosis may be difficult because of the risk of atypical antipsychotic drug induced obsessive compulsive symptoms 20. Typical antipsychotic drugs constitute a safer option in such patients. There is dearth of Indian studies on OCD co-morbid with mania. In a study investigating psychiatric co-morbidity in children and adolescent with OCD only 1 of 54 subjects had bipolar disorder21. Similarly for eating disorders; an Indian study had reported eating disorder in 1 patient of 231 patients with OCD 22. None of our subject reported symptoms of co-morbid bipolar disorder or eating disorder. The low prevalence of these disorders with OCD as evident in this and other Indian studies may be related to socio cultural differences, as prevalence of both bipolar disorder and eating disorders even among general population is high in industrialized, affluent countries linking the disorders to high socio economic status 23, 24, 25. Also, no subjects in our study met criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence or non alcohol substance abuse/ dependence other than nicotine dependence (18%). Though, there is no Indian study of alcohol or substance use in OCD, the prevalence is extremely low compared to 21% prevalence of alcohol use disorders amongst general Indian population26. This unusual finding could be partly explained by high levels of harm avoidance, low novelty seeking and dependent personality traits like exaggerated anxiety, concern, and fear of uncertainty seen in OCD patients 27, 28. Our subjects also 9 reported high level of fear, anxiety about the effect of alcohol & other substances on their general health and OCD particularly thus avoiding it. Also many avoided it for the religious and social reasons suggestive of rigid attitudes. The same could be true for none of our patients satisfying criteria of antisocial personality disorder characterized by low harm avoidance, high novelty seeking. Conclusion: This study highlights the high prevalence of one or more co-morbid psychiatric disorder in OCD. Early recognition and adequate treatment of these co-morbid disorders is crucial. Further exploration with a larger sample size is needed to assess the prevalence and impact of less frequent disorders like bipolar disorder and eating disorders on OCD patients. References 1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Principal and additional DSMIV disorders for which outpatients seek treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51(10): 1299– 1304. 2. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, et al. The epidemiology of obsessivecompulsive disorder in five US communities. Archives of General Psychiatry 1988; 45: 1094–99. 10 3. Overbeek T, Schruers K, Vermetten E, et al. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: prevalence, symptom severity, and treatment effect. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002; 63: 1106–1112 4. Denys D, Tenney N, et al. Axis I and II comorbidity in a large sample of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 2004; 80: 155–162. 5. Torres AR, Prince MJ, Bebbington PE, et al. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence, Comorbidity, Impact, and Help-Seeking in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1978-1985. 6. Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Pfanner C, et al. The clinical impact of bipolar and unipolar affective comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 1997; 46: 15– 23 7. Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. Journal of Affective Disorders 2002; 68: 1-23. 8. Ingram IM. Obsessional illness in mental hospital patient. Journal of mental science 1961; 107: 382-402. 9. Rosenberg CM. Complication of OCD. British Journal of Psychiatry 1968; 114: 477478. 10. Khess CRJ,Das I, Parial A, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder with psychotic features:---A Phenomenological study. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry 1999; 9(1): 2125. 11 11. Rasmussen SA, Tsuang MT. Clinical characteristics and family history in DSM III obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143: 317-22. 12. Bhattacharyya S, Janardhan Reddy YC, Khanna S. Depressive and anxiety disorder comorbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychopathology 2005; 38: 315-9. 13. Kamath P, Janardhan Reddy YC, Thennarasu K. Suicidal behavior in obsessivecompulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 1741-50. 14. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL. Clinical features and phenomenology of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Annals 1989; 19: 2-5. 15. Perugi G, Toni C, Frare F, et al. Obsessive–compulsive-bipolar comorbidity: a systematic exploration of clinical features and treatment outcome. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002; 63: 1129–1134. 16. Tukel R, Meteris H, Koyuncu A, et al. The clinical impact of mood disorder comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006; 256: 240–245 17. Foa EB. Failure in treating obsessive-compulsives. Behav. Res. Ther. 1979; 17: 169–176 18. Insel TR, Akiskal HS. Obsessive compulsive disorder with psychotic feature: a phenomenological analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 1986; 143: 1527-1533. 19. Mirza Hussain KA, Chaturvedi SK. Obsessive compulsive disorder with psychotic features: a case report. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 1988; 30: 315-317. 12 20. Lykouras L, Alevizos B, Michalopoulou P, et al. Obsessive Compulsive Symptoms induced by atypical antipsychotics. A review of reported cases. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol.Psychiatry 2003; 27: 333-346. 21. Reddy JYC, Reddy SP, Shobha S, et al. Comorbidity in juvenile obsessive compulsive disorder : a report from India. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2000; 45: 274-278. 22. Jaisoorya TS, Reddy JYC, Srinath S. The relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to putative spectrum disorders: results from an Indian study. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2003; 44: 317-323. 23. Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Marazziti D, Raffaelli S, Rossi G, Cassano GB. Social class and mood disorders: clinical features. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993; 28:569. 24. Okasha A, Kamel M, Sadek A, et al. Psychiatric morbidity among university students in Egypt. British Journal of Psychiatry 1977; 131: 149-154. 25. Verdoux H, Bourgeois M. Social class in unipolar and bipolar probands and relatives. J Affect Disord. 1995; 33: 181-7. 26. Ray R. The Extent, Pattern and Trends Of Drug Abuse In India, National Survey, Ministry Of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government Of India and United Nations Office On Drugs and Crime, Regional Office For South Asia 2004. 13 27. Alonso P, Menchon JM, Jimenez S, et al. “Personality dimensions in obsessivecompulsive disorder: Relation to clinical variables.” Psychiatry Research 2008; 157: 159-168. 28. Kim SJ, Kang JI & Kim CH. “Temperament and character in subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder” Comprehensive Psychiatry 2009; 50: 567-572. 14 Table 1: Sample characteristics Age Mean 30.62 Percentage Sex Female 36.0 Male 64.0 Marital status Married 50.0 Single/separated 50.0 Religion Hindu 66.0 Muslim 22.0 Buddhist 10.0 Sikh 2.0 Educational status Illiterate 4.0 Primary 6.0 Secondary 34.0 Higher secondary or more 56.0 Occupation 15 Employed 52.0 Housewife 28.0 Student / unemployed 20.0 Table 2: Comorbid disorders 16 Number (%) Major depressive episode Current 35 (70%) Past 33 (66%) Recurrent 3 (6%) Suicidality Low 19 (38%) Moderate 7 (14%) High 5 (10%) Panic disorder Current 6 (12%) Lifetime 7 (14%) Agoraphobia Current 7 (14%) Nicotine dependence Current 9 (18%) Social Phobia Current 5 (10%) Psychotic disorders Current 11 (22%) Lifetime 3 (6%) The above table includes only the psychiatric disorders for which the subject group satisfied the diagnostic criteria. 17