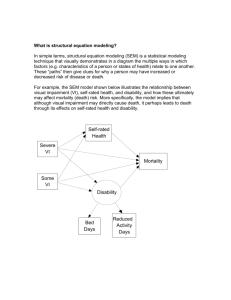

Editorial

advertisement