File - Early Childhood Education Assembly

advertisement

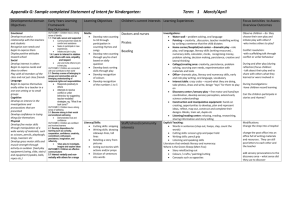

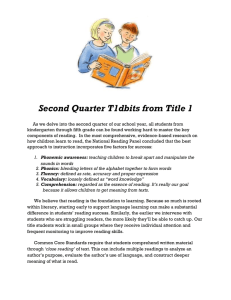

PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS November 2014 Volume 1, Number 1 Young English Learners’ Retrospective Analysis of Fluency Using E-Readers Dr. Sally Brown Georgia Southern University sallybrown@georgiasouthern.edu Abstract With the increase in multimodel forms of literacy available to emerging readers, there are questions for teachers who would like to integrate the new 21st century technologies into their literacy pedagogy. This is especially true in classrooms that serve students who are most at risk for not having exposure to new technologies. Using ethnographic tools to assess English language learners’ literacy development in a Title I classroom, this article explores using aesthetical experiences to assist with meaning construction, studies how retrospective analysis leads to student agency, and describes how multiple modes enhances learning. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 51 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS “[Fluency] is like when I read and it sounds like a good story. You get that it’s a funny book or a scary book or excitement and stuff like that. It makes me want to hear stories more and more.” [David, 2013] Luis sits with his Nook e-reader in the corner of the book center with the digital book Baghead (Krosoczka, 2002) open. He taps the read and record tab on the first page. Luis begins reading and recording, “On Wednesday morning, Josh had an idea.” After recording, Luis listens to his own voice, smiles, and moves to page two where he reads and records, “A very BIG idea. A very BROWN idea.” in a steady voice. Once again he listens before moving on, but this time he shakes his head no. He says to himself, “That not how to say it. I gotta do it over. Yea. Better.” Luis taps to erase and rerecord page two only this time he emphasizes the words big and brown which appear as large, bold, uppercase letters in the book. His voice adds an element of loudness as well as extensions of the words like, “BIIIIIGGG.” After listening to the second recording, Luis whispers, “Uh, huh,” to himself and quickly moves to the next page (Field notes, March, 2013). This vignette captures the essence of this research study investigating how the read and record functions of digital picture books on an e-reader impact the reading experiences of young English learners. As we move into the 21st century it is vital that low income multilingual students be afforded the contemporary communication and learning opportunities made available to White, middle-class, English speaking students. Many teachers tend to relegate technology applications to drill and skill for minority and working-class students (Gray, Thomas, & Lewis, 2010; Lichter, Qian, & Crowley, 2006; NCES, 2000) and ignore the multiliteracy capabilities of young students (Siegel, Kontovourki, Schmier, & Enriquez, 2008). Young emergent bilinguals compose approximately one-fifth of young children, and lag behind their native English speaking peers in reading (Frede & García, 2010). Hernandez (2011) found that students who fail to read PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 52 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS proficiently by the end of third grade are four to six times more likely to drop out of high school than proficient readers. So, there is a need for these students to engage in rich, authentic, technobased literacy activities within their early childhood classrooms (Warschauer & Matuchniak, 2010). Reading as a Meaning Making Process A psycholinguistic model of reading is based on the premise that written language makes sense and serves as meaningful forms and functions in daily literacy practices (Goodman, 2001). “Every reading act is an event, or a transaction involving a particular reader and a particular pattern of signs, a text, and occurring at a particular time in a particular context” (Rosenblatt, 1994, p. 1059). So, reading is an active process where the reader selectively tests meaning-based predictions through confirmations or rejection of hypotheses. This integration of multiple sources of information (semantic, syntactic, graphophonemic, and pragmatic) is the way readers construct meaning when interacting with texts (Goodman, 1996). Therefore, during word identification the reader utilizes the sequence of words to eliminate alternatives rather than decoding individual letters and words in isolation (Smith, 2011). These language systems must be supported by classroom literacy instruction that integrates these processes in socially situated authentic contexts that do not focus on skill mastery. Reading in a New Language When working with students who are learning to read in English as a new language, it is important to consider the individual student. Genishi and Dyson (2009) remind us to draw from the premise that children learning a new language may take different paths at various rates as they interact with others in a multitude of sociocultural contexts. English learners need time to PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 53 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS transition from slow to fluent reading as they learn aspects of the English language like vocabulary, syntax, and prosody through exposure to texts at various reading levels (Kuhn & Rasinski, 2009). In addition, second language fluency development requires a long incremental learning process and practice should minimally focus on getting the language exact (Grabe, 2009). Pedagogy for teaching English learners to read should be guided by the premise that reading equals meaning construction without a focus on word-by-word decoding. Comprehension is critical for academic success and this means English learners should have authentic experiences with texts at appropriate levels (Freeman & Freeman, 2007). Research shows the speed of a reader is influenced by a reader’s purpose, life experiences, and linguistic resources. One should not make comparisons between readers, different readings of the same text, or reading on different days due to the complexities and dynamic nature of reading (Flurkey, 2008). Whitmore, Martens, Goodman, and Owocki (2004) remind us that “No child can be viewed as independent of her sociocultural identity, her political status, or her linguistic heritage (p. 318).” As a result considerations for individual differences must be accounted for as language learning progresses over time. Fluency Fluency is at the forefront of many literacy debates for educators and Allington (2012) reports it as being one of the biggest challenges facing readers. He is clear that fluency not only means rate, but is inclusive of other factors like intonation and phrasing. Numerous commercial programs and standardized testing like DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Literacy Assessment) narrow fluency to almost exclusively mean rate (Goodman, 2006). Thus, many students end up reading accurately and quickly with little comprehension (Allington, 2006). PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 54 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Given the increasing pressure on teachers to narrowly focus on test scores (Ravitch, 2010), some teachers tend to focus on rate to the exclusion of other important aspects of fluency that are essential for comprehension. In particular, the transactive nature of reading, an active meaning making process, gets lost (Altwerger, Jordan, & Shelton, 2007). Raskinski (2010) suggests that fluency is fostered through authentic oral reading when students engage in quick reading with meaningful expression. Authentic reading instruction pivots on comprehension. Requiring both wide and deep expressive oral reading only enhances meaning (Raskinski, 2012). Reutzel, Jones, Fawson, and Smith (2008) highlight the importance of students receiving feedback about their fluency in order to transfer oral reading skills to silent reading. Monitoring fluency along with comprehension as self-regulating processes leads readers toward independence in navigating texts by using strategies to repair and improve understanding (Reutzel, 2006). Internalizing a model of fluent reading using one’s self or peer coaching assists in this self-monitoring development (Raskinski, Homan, & Biggs, 2009). Multimodal Literacy Multimodality, a social semiotic perspective, refers to the interconnectedness of writtenlinguistic modes with other ways of making meaning such as visual and aural. These new ways of literacy learning require an expanded sense of communication that values a wide range of texts with variations in form and function (Kalantzis & Cope, 2012). Meaning makers, readers, actively use all available forms of representation to transform or reconfigure modalities. In order for this to occur, students must be agentive in the dynamic literacy process to be dynamic and innovative. Shifting from conventions such as grammar and transmission of knowledge to unfamiliar domains where learners draw from multiple metalanguages and a mixture of modes to PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 55 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS both interpret and express a repertoire of ideas is essential in meeting the needs of diverse students (Cope & Kalantzis, 2013). Literacy and technology operate concurrently when students engage in multimodal learning activities. Contemporary classroom interactions require bridges between the new literacies students engage with outside of school and available classroom technology tools. Young learners are quick to construct meaning through interactions with multimedia texts in fluid ways that transform traditional practices (Walsh, 2010). Given the importance of technology for 21st century citizenship and the changing nature of a global world, a multimodal pedagogy is indispensable (NCTE, 2008). Context and Methods This research is extracted from a year-long research project in an urban, Title I, public school, third grade classroom. The participants (pseudonyms) were seven English learners whose first languages were Spanish, French Creole, and Vietnamese (Table 1). The project looked closely at the literacy development of these students as they read and recorded digital books on e-readers. The Barnes and Noble Nook Tablet was used because it afforded a record and play option to be used with a variety of children’s literature in a digital format. The recording function allowed students to record in small page-by-page chunks with immediate listening capabilities before moving on to the next part of the story. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 56 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Table 1 Student Information. Student First (Pseudonym) Language ACCESS Score* (August) Instructional Reading Level (May)** 4.5 ACCESS Instructional Score* Reading (May) Level** (August) 6.0 L Darly French Creole Arturo Spanish 2.0 3.5 E K Luis Spanish 4.1 5.7 K M Andrea Spanish 4.0 5.5 M P David Spanish 5.0 6.0 M O Mai Vietnamese 1.0 3.9 E I N *ACCESS – Assessing Comprehension and Communication in English State to State for English Language Learners (6 point scale) **(Fountas & Pinnell, 1999) The students met in small groups which were comprised of both English learners and English-only peers. Using the Nooks as a tool, these heterogeneous groups met with the researcher twice per week for literacy instruction. Students listened to the cyber voice read a story, practiced reading it orally, and then recorded themselves reading the texts. During the recording sessions the participants listened to their performance on each page and determined if re-recording was necessary based on their own evaluation of their reading. Once the entire story was recorded, each student evaluated their fluency (including pausing, phrasing, stress, intonation, and rate) (Fountas & Pinnell, 2006) using the student developed rubric. The English learners developed goals tied to improving their fluency through the writing reflection section of PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 57 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS the rubric (Appendix A). In addition, the students listened to one another’s recordings and completed a peer evaluation rubric. An ethnographic perspective (Green & Bloome, 1997) was used to focus on literacy practices (the ways of being and doing with both words and oral recordings) involved with personal literary experiences with digital texts given specific social and cultural contexts (Street, Pahl, & Roswell, 2009). By connecting multimodality and ethnography, reading was viewed as a situated social practice with the literacy event as the unit of analysis (Moss, 2003). In the case of this study, digital picture books involving rich dialogue served as a stimulus for recording and reflecting upon the use of voice as a tool to construct meaning. In other words, the participants determined how each text was read and the meaning associated with the images, characters, settings, and events. Ethnographic tools documented the study as the researcher assumed the role of participant observer (Spradley, 1980) which varied from passive to active according to the evolving context. All of the small group experiences were documented through field notes and videotaping with selected events being transcribed (Glesne, 2010). Each student participated in a reflective interview (Seidman, 2006) after completing five read and record events. Translators were used when appropriate. In addition, students created a rubric based on the elements of reading they felt were most important. A five star system was used for evaluation since the students were accustomed to using this model to write online book reviews. The five evaluative statements were followed by one open-ended response which required students to set a reading goal (for themselves or a peer). This rubric was modified slightly to create a peer evaluation rubric on fluency as well. Additionally, retellings of the stories were evaluated on a 10-point scale. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 58 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS The field notes, interviews, transcripts, retellings, and open-ended responses were analyzed using the constant comparison method (Charmaz, 2006) regarding student language use associated with particular aspects of the reading process, discursive patterns, and agentive stances for shaping reading and re-reading of texts (Gee, 2005). After initial coding (Table 2), a more intensive tacit review of the codes was conducted to provide a clearer picture of participants' viewpoints and understandings of fluency and comprehension. This focused Table 2 Coding Chart Sample Initial Codes Refined Codes Themes Engagement Enjoyment Comprehension Humor Talk Reading Author Sounding Expressive Voice Font/Print Size Influence Self-Guided Learning Self-Revision Rereading Sense of Accomplishment Choice Time Spent with Text Instructional Power Control over Technology Tools Immediate Performance Feedback Written Feedback Negotiation through Talk Peer-Guided Learning Reading to Understand Aesthetic Experiences Cyber Voice-Like Reading Self-Teaching Student Agency Student Voice Student Choice Self-Evaluation PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 59 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS coding was more selective and permitted the synthesis of larger ideas across data (Charmaz, 2006). For example, the initial codes of engagement, enjoyment, comprehension, and humor formed a larger category called reading to understand which fell into a broader theme called aesthetic experiences. These codes intersected to illustrate the ways in which students read and reread for the personal purpose of meaning construction. In addition, descriptive statistics were used to report the quantitative data gathered from the peer and self-evaluations rubrics. This data was embedded into the larger ideas to support the qualitative findings. The following sections report the findings revolving around the three major themes of the study: aesthetical experiences assisting with meaning construction, retrospective analysis leading to student agency, and multiple modes enhancing learning. Transcripts as well as quantitative data provide examples of student voices and perceptions of the reading process using the ereaders. Findings Aesthetical Experiences Assist with Meaning Construction The students felt the goal of reading and listening to stories was enjoyment, engagement, and understanding above all else. For them this meant being able to hear changes in the reading that aided in comprehension like different characters’ voices, feelings of excitement, and the addition of humor. In the interviews and small group interactions participants repeatedly focused on the ways in which good reading sounded like talk (Goodman, 2001). For example, after Arturo listened to a story read by a peer, he commented, “You read like you talk. You sounding like the author [cyber voice] when you read. It’s good. I get your story.” His comments PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 60 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS reflected the importance of an aesthetic reading experience for meaning construction and enjoyment (Rosenblatt, 1978). Students also reflected upon their own readings of the five pieces of children’s literature, and evaluated themselves lowest (an average of 3.7 out of 5) in the area of word reading or accuracy (Figure 1). Even though students made miscues or skipped words while reading, these Figure 1 Retrospective Self-Analysis Using 5 Star Rubric Average Rating 4.3 4.2 4.1 4 3.9 3.8 3.7 3.6 3.5 3.4 Medium Reading Word Reading Change in Voice Volume Punctuation were not significant enough to alter to the overall meaning of the text. For example, after listening to his recording of Awesome Dawson (Gall, 2013), Luis smiled and leaned over to Henry and said, I did pretty good on this one. You want to listen? I have a good robot cow voice. Listen. ‘The vacu-maniac has a brain made of cat food, Dawson’ [Read a line from PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 61 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS the text in a robotic voice].Yea, yea, you will love it cuz I made it funny. I did mess up on some words. [Flipped pages on Nook.] Like right here. I forgot this word [hurricane] and one, no two more, well more than that. I think. It won’t matter cuz you can still get it [understand the story]. In this instance Luis’s excitement about his production or recording was shared with Henry. His talk focused on the aesthetic or joy of reading a humorous story during which he perfected a cow voice that matched the character’s inanimate being. Luis noted that his reading was not perfect in terms of word accuracy, but determined that lack of perfection would not interfere with meaning and enjoyment. The large number of words Luis was able to identify automatically coupled with elements of prosody supported comprehension (Kuhn & Rasinski, 2009). Goodman (1996) recognizes the role of accuracy in the reading process and notes that accuracy does not ensure comprehension just as inaccuracy does not necessarily signal lack of comprehension. It was clear in this example that Luis was focused on reading for meaning as he used available resources to make sense of the text. As an English language learner Luis concentrated more on prosodic features of the reading and less on being exact with the language (Grabe, 2009). Retellings The process of creating recordings through multiple experiences with each text enriched students’ retellings of the stories (Figure 2). Each student controlled the amount of interactions with each text. For example, Mai listened to Red and Yellow’s Noisy Night (Selig, 2012) three times before she determined she was ready to record her own reading of the text. It seemed as if PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 62 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Mai was listening closely to the cyber voice as a scaffold for pronunciation of the English words (Reutzel & Cooter, 2011) and understanding of story events. Figure 2 Retelling Scores Average Rating 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Daredevil Stunt Show Baghead Awesome Dawson Red & Yellow You Will Friend Once comfortable with words and meaning of the text, Mai recorded her version. Observations indicated Mai’s repeated attempts at recording were focused on expression or changing her voice and using punctuation. Rate and word accuracy received less attention. Overall, Mai transacted with this particular text on seven occasions over a two week period. At the end of this time Mai retold the story accurately with supportive details: Yellow man and red man live in tree. Red man make noise with brown thing. Yellow man mad. He want sleep. Not happy. Red, he make happy song music. Yellow man get happy. He sleep. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 63 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Mai recalled the main details in an appropriate sequence and identified the main characters (which were indeterminate animals) while referring to them as “red man and yellow man.” She was unsure of the English vocabulary word to represent a musical instrument which was called a “strummy” in the story. However, she noted the importance of this “brown thing” in the story as she commented on yellow man being mad and wanting to sleep. Her experiences with this text were not bound by teacher direction, probed with scripted questions, or timed. They were self-guided in a way that supported her construction of meaning. Mai’s work as a reader was not focused on calling words in isolation, rather to construct an understanding of the whole (Rosenblatt, 1995). Retrospective Analysis Leads to Student Agency The retrospective analysis process was twofold. First, the students used their own judgment to analyze and initiate changes to their recordings in the midst of reading each page. Second, upon completion of recording an entire text, students reflected upon their overall performance in reflexive ways and utilized the rubric to envision improvements for future readings (Mills & Jennings, 2011). The immediate feedback (listening to the recordings) and opportunities for revision (repeated recording) created an active space for student agency. The artifacts, recordings and rubrics, appeared to be used to mediate students’ thoughts and actions about fluency performance (Holland, Lachicotte Jr., Skinner, & Cain, 1998). The following transcript highlighted the role of agency, control over one’s learning and resources, enacted by students through the retrospective analysis process (Holland et al., 1998). David explained the importance of student agency in an interview. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 64 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS I like with Nooks I get to decide. I listen, then, when I do not like it [recording], I erase it. So easy. No one else gets to hear it. I am the boss and I can make it better and better and better until I like it. Like, I make lots of different kinds of voices, like that boy and then there was a momma bear. They got to sound different, you know. Don’t read them the same. Make yourself loud when you see big words. Sometimes you have to read quiet like baby bear, so you get what’s happening… When David was asked how the Nooks supported him as a reader, he began by talking about control over decision making and being the boss of his learning. This was very different from reading instruction with his teacher where the basal and accompanying materials and lessons were implemented without student input or choice. David noticed and articulated the importance of controlling available resources given the social context and made decisions about the ways in which he used the repeated recordings to improve his oral reading fluency (Fisher, 2010). David also acknowledged the ways in which the peer-evaluation rubrics empowered him as a reader. Upon completion of recording You Will Be My Friend (Brown, 2011), David’s small group traded their Nooks with one another, listened to each other’s recordings, and completed rubrics about the performances. Andrea listened to David’s and wrote the following comment to him, “You did okay but I think you do not use the excited [exclamation] marks. You did not sound excited.” Upon receiving this feedback, David responded, You see what Andrea said. She said I do not do the excited ones. I did. Well, let me just listen, listen one more time. [Put on headphones and listened to his recording.] Oh, oh, maybe here [Talked to self.] Oh, oh. Kinda. Yea, PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 65 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS this one. [Stopped listening and removed headphones.] At first David seemed disturbed by Andrea’s comments, but after listening to his recording he came to a different conclusion. He remarked, “Hey, Dr. XX I get it. Andrea said that I do not read things with excited. I thought she was making it up. No. I really did not do it. I heard me. I can do better. Can I record this again?” David utilized the rubric comments or discussion with a peer as a resource to respond it a positive way to this learning opportunity afforded to him (Fisher, 2010; Wassell, Hawrylak, & LaVan, 2010). The peer feedback led David to make a choice that led to improvement in his reading performance (Reutzel et al., 2008). Multiple Modes Enhance Learning Students were also quick to articulate judgments about any readings that “sound[ed] like a robot” since this interfered with their construction of meaning and the pleasure associated with listening to a story. This occurred across contexts as students used language to transform words on a page into a multimodal production using meaning making resources available to each individual (Kalantzis & Cope, 2012). The event below occurred as a small group of students were sitting around a table recording their readings of Kel Gilligan’s Daredevil Stunt Show (Buckley, 2012). The students heard one another recording and spontaneously made comments. Arturo: [Read in a monotone voice.] The potty of doom! Done, done, done. Darly: [Watched Arturo and listened to his reading.] Hey, I just finished that part. That’s not how you do it. Arturo: [Took headphones off.] What are you saying? Darly: You read it boring like. Look at his face. [Pointed to image.] He is yelling. You can not read it like that. And anyway that is not how it goes. It is like this. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 66 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS [Read with expression.] The potty of doom! Dun-Dun-Duhhhhh! See it is not done, done, done. Katy: [Interrupted.] Hey, you can listen to mine. I did that page already. [Flipped to the appropriate page on her Nook. Unplugged headphones and played page for boys to hear.] Arturo: Oh, I get it. He is screaming it at his momma. Let me try mine again. [Rerecorded page.] Darly: [Listened to Arturo record.] Yea, you get it now. Better. [Laughed.] Arturo worked to remake the written text including visual images into an audio version in a way that represented his construction of the text. Darly interrupted when he disagreed with the way Arturo articulated the author’s words. The text served as a prompt for talking about fluency aspects of reading and an opportunity to analyze the different ways one might transform a phrase when reading aloud (Moss, 2003). In a way Darly realized that language was only part of the construction of knowledge and the need for the aural version to include additional features that is not available to written communication (Kress & Jewitt, 2003). The message of the recording and visual images required more of a combination of modes in order to carry the entire meaning of the story in a way in which an individual reader uses voice to remake the unique meaning of the text (Cope & Kalantzis, 2013). Each of the themes showcases the ways technology, particularly e-books with a read and record function, supports student learning in terms of reading comprehension and fluency. The students forefront the essential role of expression and meaning making and relegate accuracy and PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 67 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS rate to a smaller role in the reading process. Although this study focused on third grade English learners, the findings may be applicable to other grade levels. Discussion Repeated reading, recording, and analyzing rubrics were all resources the students drew from to enhance their development as readers (Kuhn & Rasinksi, 2009; Reutzel et al., 2008). Although growth in instructional reading levels cannot be solely attributed to this project (as indicated in Table 1), this data does provide insight into the larger picture of these students as readers who are working toward understanding text of which fluency is embedded. Improvements in fluency did not come from final products, but in the learning and interactions that occurred during the process (Whitmore et al., 2004). The data examples suggest that accuracy and rate play a small role in reading comprehension and therefore, reading rate and accuracy should not be the forefront of literacy instruction (Allington, 2012; Altwerger, Jordan, & Shelton, 2007). Instead, the central focus should be on the construction of meaning (Goodman, 1996). In all of the literacy events, students’ fore-fronted meaning construction and aesthetical reading experiences over accuracy and pace. This was evident during the multimodal construction where students only partially relied on language and instead, captured other modes to ensure a rich experience listening to a text (Kress & Jewitt, 2003). Each reader reconstructed the sounds of the written words in an individual process of interpreting multiple texts given the social context of school (Rosenblatt, 1978). Transacting with texts was a personal experience that may have been motivated by creating a performance for others to enjoy (Rasinski et al., 2009). PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 68 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Flexible teaching methods that take into account the students’ inner clock as opposed to a scripted, hurried curriculum are necessary for English learners (Genishi & Dyson, 2009). During this study, there were no stop watches recording the number of words students read per minute. Students used their own agency to engage in multi-literate experiences that varied individually and allowed each student a different time span for achieving fluency (Kenner & Gregory, 2013). This dynamic view of reading embraced a process that varies with the student, text, prior experiences, and available resources (Flurkey, 2008). Equally important is the use of innovative teaching methods and high quality digital texts that engage students in literacy classrooms (Reutzel & Cooter, 2011; Schugar, Smith, & Schugar, 2013). Motivation is essential for readers working to develop competency in fluency (Thoermer & Williams, 2012). Digital tools like the Nooks can provide many opportunities for literacy development that go beyond traditional forms of reading and writing (Walsh et al., 2007) and provide avenues for both wide and deep reading (Rasinski, 2012). References Allington, R. (2012). What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-based programs (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Allington, R. (2006). Fluency: Still waiting after all these years. In S. Samuels and A. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about fluency instruction (pp. 94-105). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Altwerger, B., Jordan, N., & Shelton, N. (2007). Rereading fluency: Process, practice, and policy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Author. (2013). Field notes. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 69 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2013). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. In M. Hawkins (Ed.), Framing languages and literacies: Socially situated views and perspectives (pp. 105-135). New York: Routledge. Fisher, R. (2010). Young writers’ construction of agency. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10(4), 410-429. Flurkey, A. (2008). Reading flow. In A. Flurkey, E. Paulson, and K. Goodman (Eds.), Scientific realism in studies of reading (pp. 267-304). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum. Frede, E., & García, E. (2010). A policy and research agenda for teaching young English language learners. In E. García & E. Frede (Eds.) Young English language learners: Current research and emerging directions for practice and policy (pp. 184-196). New York: Teachers College Press. Fountas, I., & Pinnell, P. (2006). Teaching for comprehending and fluency: Thinking, talking, and writing about reading, K-8. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Fountas, I., & Pinnell, G. (1999). Matching books to readers: Using leveled books in guided reading K-3. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Freeman, D., & Freeman, Y. (2007). English language learners: The essential guide. New York: Scholastic. Gee, J. (2005). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. Glesne, C. (2010). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (4th ed.). New York: Pearson. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 70 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Goodman, K. (2006). A critical overview of DIEBLS. In K. Goodman (Ed.), Examining DIBELS: What it is and what it does (pp. 1-32). Brandon, VT: Vermont Society for the Study of Education, Inc. Goodman, K. (1996). On reading: A common-sense look at the nature of language and the science of reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Goodman, Y. (2001). The development of initial literacy. In E. Cushman, E. Kintgen, B. Kroll and M. Rose (Eds.), Literacy: A critical sourcebook (pp. 316-324). New York: Bedford/St. Martins. Goodman Y., & Marek, A. (1996) Retrospective Miscue Analysis in the Classroom. Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owen. Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gray, L., Thomas, N., and Lewis, L. (2010). Teachers’ use of educational technology in U.S. public schools: 2009 (NCES 2010-040). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC. Green, J., & Bloome, D. (1997). Ethnography and ethnographers of and in education: A situated perspective. Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts, 181-202. Hernandez, D. (2011). Double jeopardy: How third-grade reading skills and poverty influences high school graduation. New York: The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Holland, D., Lachicotte Jr., W., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2012). Literacies. New York: Cambridge University Press. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 71 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Kress, G., & Jewitt, C. (2003). Introduction. In C. Jewitt & G. Kress (Eds.), Multimodal literacy (pp. 1-18). New York: Peter Lang Publishing. Kuhn, M., & Rasinski, T. (2009). Helping diverse learners to become fluent readers. In L. Morrow, R. Rueda, and D. Lapp (Eds.), Handbook of research on literacy and diversity (pp. 366-376). New York: Guilford Press. Lichter, D., Qian, Z., & Crowley, M. (2006). Race and poverty: Divergent fortunes of America’s children? Focus, 24(3), 8-16. Mills, H., & Jennings, L. (2011). Talking about talk: Reclaiming the value and power of literature circles. The Reading Teacher, 64(8), 590-598. Moss, G. (2003). Putting the text back into practice: Junior-age non-fiction as objects of design. In C. Jewitt & G. (Eds.), Multimodal literacy (pp. 73-87). New York: Peter Lang Publishing. National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2000). Teacher use of computers and the Internet in schools. Washington, DC: United States Department of Education. National Council of Teachers of English (2008). The NCTE definition of 21st century literacies. Retrieved November 3, 2013, from http://ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentdefinition. Rasinski, T. (2012). Why reading fluency should be hot! The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 516-522. Rasinski, T. (2010). The fluent reader: Oral reading strategies for building word recognition, fluency, and comprehension (2nd ed.). New York: Scholastic Professional Books. Rasinski, T., Homan, S., & Biggs, M. (2009). Teaching reading fluency to struggling readers: Method, materials, and evidence. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 25(2), 192-204. Ravitch, D. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system: How testing and PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 72 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS choice are undermining education. New York: Basic Books. Reutzel, R., & Cooter, R. (2011). Strategies for reading assessment and instruction: Helping every child succeed. New York: Pearson. Reutzel, R., Jones, C., Fawson, P., & Smith, J. (2008). Scaffolded silent reading: A complement to guided repeated oral reading that works!, The Reading Teacher, 62(3), 194-207. Reutzel, R. (2006). “Hey, teacher, when you say ‘fluency,’ what do you mean?” In T. Rasinski, C. Blachowicz, and K. Lems (Eds.), Fluency instruction: Research-based best practices (pp. 62-85). New York: Guilford Press. Rosenblatt, L. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. Ruddell, M. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (pp. 10571092)(4th ed.). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Schugar, H., Smith, C., & Schugar, J. (2013). Teaching with interactive picture e-books in grades K-6. The Reading Teacher, 66(8), 615-624. Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research (3rd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. Siegel, M., Kontovourki, S., Schmier, S., & Enriquez, G. (2008). Literacy in motion: A case study of a shape-shifting kindergartener. Language Arts, 86(2), 89-98. Smith, F. (2011). Understanding reading: A psycholinguistic analysis of reading and learning to read (6th ed.). New York: Routledge. Spradley, J. (1980). Participant observation. New York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. Street, B., Pahl, K., & Roswell, J. (2009). Multimodality and new literacy studies. In C. Jewitt PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 73 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS (Ed.). The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 191-200). New York: Routledge. Thoermer, A., & Williams, L. (2012). Using digital texts to promote fluent reading. The Reading Teacher, 65(7), 441-445. Walsh, M. (2010). Multimodal literacy: What does it mean for classroom practice? Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 33(3), 211-239. Walsh, M., Asha, J., & Sprainger, N. (2007). Reading digital texts. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(1), 40-53. Warschauer, M., & Matuchniak, T. (2010). New technology and digital worlds: Analyzing evidence of equity in access, use, and outcomes. In A. Luke, J. Green, & G. Kelly (Eds.), Review of research in education: What counts as evidence in educational settings? Rethinking equity, diversity, and reform in the 21st century (pp. 179-225). Vol. 34. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Wassell, B., Hawrylak, M., & LaVan, S. (2010). Examining the structures that impact English language learners’ agency in urban high schools: Resources and roadblocks in the classroom. Education and Urban Society, 42(5), 599-619. Whitmore, K., Martens, P., Goodman, Y., & Owocki, G. (2004). Critical lessons from the transactional perspective on early childhood research. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 4(3), 291-325. Children’s Literature Cited Brown, P. (2011). You will be my friend. New York: Hachette Book Group. Buckley, M. (2012). Kel Gilligan’s daredevil stunt show. New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 74 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Gall, C. (2013). Awesome Dawson. New York: Hachette Book Group. Krosoczka, J. (2004). Baghead. New York: Random House Children’s Books. Selig, J. (2012). Red & yellow’s noisy night. New York: Sterling Publishing. PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 75 PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS Appendix A Self-Evaluation Rubric Name ___________________________________________________________________ Retrospective Fluency Self-Evaluation 1. Medium reading (not too fast or too slow) . 2. Read all the words without messing up. 3. Changed voices for characters and action. 4. Could hear the words. 5. Used punctuation marks. What I would like to do better the next time I read: ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ PERSPECTIVES AND PROVOCATIONS | Volume 4, Number 1, 2014 Brown 76