The Leadership Grid

advertisement

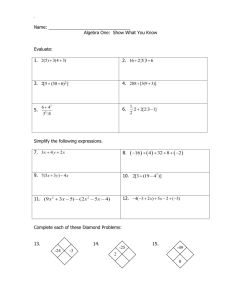

Running Head: THE LEADERSHIP GRID The Leadership Grid Jennifer Bylan Louis Latimer Jason Thigpen Erica Neidhart Organizational Behavior & Human Resource Management July 31, 2011 Gail Cullen Southwestern College Professional Studies 1 THE LEADERSHIP GRID 2 Abstract The Leadership Grid was originally developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton during their research time at the University of Texas between 1950 and 1960. Many have compared their Leadership Grid against the Situational Leadership Theory developed by Hersey and Blanchard. Some of these differences include the degree of interaction between the two common variables addressed by both theories. These two common variables are task and people. The two theories contradict in how these variables interact. In addition, the Leadership Grid is concentrated mostly on the attitude of the leader. Situational Leadership, on the other hand, concentrates on the maturity level of the follower and the appropriate leadership behaviors that correspond with each. Finally, the Leadership Grid believes that there is one best way to react in a certain situation, while Situational Leadership contends that there is no such “one best” leadership style for any given situation. THE LEADERSHIP GRID 3 Managerial Grid History and Description The Managerial Grid was initially developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton as a diagnostic tool which would allow managers to assess their leadership style or behavior (Dictionary of Human Resource Management 2001). Blake and Mouton worked together at the psychology department at the University of Texas between 1950 and 1960. It was there that they first developed the concept of the Managerial Grid (Robert R Blake and Jane S Mouton: The Managerial Grid 2002). In 1955, Blake and Mouton founded Scientific Methods, Inc. to provide consulting services that were based on the application of behavioral science in the workplace. The company grew to include Grid-based organization and development programs in several areas. It operated in over 30 countries worldwide. In 1997, Blake sold Scientific Methods, Inc. to an associate due to the death of Jane Mouton in 1987. It continues to this day under the name Grid Organization Development. Blake remains involved in the company as an associate (Robert R Blake and Jane S Mouton: The Managerial Grid 2002). Rensis Likert, a behavioral scientist, provided the initial ideas that were used as the groundwork for the practice management transformed by Blake and Mouton. In addition, Blake and Mouton built on studies that were produced by Ohio State University and the University of Michigan in the 1940’s. One of the goals of these studies was to identify the behavioral characteristics of successful leaders (Robert R Blake and Jane S Mouton: The Managerial Grid 2002). The foundation of their research not only included behavioral science but included their own evaluations of leadership characteristics. It was at this point that they identified two fundamental drivers of Managerial behavior. The drivers identified are as follows: 1: Concern for Production (getting the job done): the degree to which a leader emphasizes concrete objectives, organizational efficiency and high productivity when deciding how best to accomplish a task. THE LEADERSHIP GRID 2: Concern for People (those that are doing the work): the degree to which a 4 leader considers the needs of team members, their interests and areas of personal development when deciding how best to accomplish a task. ( Blake Mouton Managerial Grid, 2011) Blake and Mouton found that a manger who focused exclusively on either of these to the omission of the other would promote an atmosphere of dissatisfaction and conflict or loss of goals and objectives regarding production (Blake, Mouton 1967). Blake and Mouton developed a Grid framework to display the management behaviors, with concern for production on the X axis or bottom and concern for people on the Y axis or side. Both concerns were given nine degrees intensity ranging from low level concern at one to high level concern at nine (Brolly 1967). There are a total of eighty-one combinations of concerns represented on the Managerial Grid. The main emphasis, however, is focused on the theories in the corners and the middle of the Grid. These are the most distinct styles and the ones identified most often in managers (Blake, Mouton 1975). With this emphasis, there breaks out to five major areas of focus for managers. 1: Nine-One Behavior (9, 1: represented in the bottom right corner of the grid): this behavior style of management has the maximum concern for job accomplishment with the least concern for the people doing the work. This behavior corresponds to the traditional authority-based, command and control behavior. This behavior has been titled as “Authority-Obedience” leadership. This leader sees “workforce needs as secondary to the need of a productive and efficient workplace. He might have very strict and autocratic work rules, and perhaps view punishment as the best motivational force.” (Blake & Mouton, 2011) 2. One-Nine Behavior (1, 9: represented in the upper left corner of the grid): this behavior style of management represents the maximum concern for people and the THE LEADERSHIP GRID 5 minimum concern for production. This is known as the “Country Club” behavior style of management which focuses on human relations to the detriment of production. If a leader uses this type of leadership style, production may suffer as well as the effectiveness of the organization. With a lack of direct supervision and control, employee motivation and focus may waiver from the goals set forth by the company mission. 3. One-One Behavior (1, 1: represented in the lower left corner of the grid): this behavior represents a style that has the minimum concern for both production and people. It is believed that this leader is the least effective. Not only does this leader have limited concern for creating efficient systems but they have limited drive for creating a motivating or satisfying work environment. Employees under this type of leadership tend to be extremely unsatisfied and unmotivated. 4. Five-Five Behavior (5, 5: represented in the middle of the grid): this behavior represents a middle-of-the-road manager, one who attempts to maintain a balance between both concerns. This manager strives to be fair but firm, do the job but find a comfortable tempo, this style is also known as the “organization man” (Blake, Mouton 1975). While some might view this as the ultimate solution to meeting the two conflicting views, leaders that use this type of style end up compromising both. Because there is no main focus on either production or people, then average becomes the norm – average performance and average results. “Workers may end up moderately motivated and satisfied, and production may only become moderately effective.” (Blake & Mouton, 2011) 5. Nine-Nine Behavior (9, 9: represented in the upper right corner of the grid): this behavior integrates the maximum attention to both people and production, and is considered the most effective approach. A person who manages with this behavioral THE LEADERSHIP GRID 6 style stresses understanding and agreement through involvement, with participation and an interdependent relationship as the key to solving boss-subordinate problems (Blake, Mouton 1975). Blake and Mouton later added a third dimension to the Managerial Grid which was depth or thickness. This was referred to as the time the Managerial behavior was maintained in any given situation or interaction, particularly under pressure from tension, frustration, or conflict (Blake, Mouton 1967). If a manager’s dominate approach to situations is from a nine-nine point of view, the time he will be able to maintain that approach in the face of conflict or tension before he or she shifts to another behavioral style is the depth. If the manager shifts under little pressure that would be noted as a nine-nine-one. At the other end would be the manager who continues to restrain from shifting in the face of what appears to be great difficulties. In that case the manager’s approach would be nine-nine-nine (Blake, Mouton 1967). Similarities between Leadership Grid and Situational Leadership Situational Leadership demands that a leader adapt their style based on the individual and the situation that is occurring. This means that a leader is not able to have a dominate style of leadership that she primarily relies on, but rather it constitutes the use of many different leadership styles to manage her subordinates based on the given situation at that time. A situational leader’s goal is to develop his or her subordinates and for the overall organization to be successful (Gupta, 2009). Similarly, within the leadership grid you have several different categories that determine the type of leadership style that the leader needs to employ. The Leadership Grid provides a structure for accessing leadership in a generic way. It is a tool that allows leaders to determine what style of leadership to use while working with their subordinates (Promoting Thought Leadership, 2011). Every leader and manager is different and each one has different goals. On the same token each subordinate is different and also has different goals and has different motivations. No one type of leadership is right for each THE LEADERSHIP GRID situation and the way to motivate one subordinate will not be the same with the other subordinates. The leadership grid locates where one leadership style falls and then helps to identify areas of improvement for weakened leadership (Blake Mouton Managerial Grid, 2011). The similarity between the leadership grid and situational leadership addresses the leader’s ability to change his or her priority due to any given situation. A leader can be people oriented at a certain situation. That same leader, during other situations, can shift his priorities and become more result oriented. The similarity is in the fact that the leader can adapt to the needs of the organization or the employees depending on the current circumstances. There are two variables that the leadership grid concerns itself with, the people variable and the result or goal variable. Since leadership can be exercised in so many different ways the two variables are independent to each other. Inside the grid there is no way to exercise 7 THE LEADERSHIP GRID 8 leadership unless both tasks and people are present at the same time as the leader thinks about how to execute leadership (Blake & Mouton, 1982) The major issue in situational leadership as well as in the leadership grid is how these two issues are reconciled together (Blake & Mouton, 1981). It is difficult, to say the least, to find the similarities between the two theories. Some might say that there are not any similarities between the Leadership Grid and Situational Leadership. However, even though the two theories are based on two different ideas they do share on glaring commonality. Both schools of thought try to reconcile the relationship between people and task and how a leader balances between the two of them (Blake & Mouton, 1982). This seems to be the one common thread that weaves these two theories together. On the other side of the coin are the extreme differences between the two, which are address in the next section. Differences between Leadership Grid and Situational Leadership We have discussed the similarities of the leadership grid and situational leadership now we are going to look at the differences. There are a few differences that are worth mentioning. First, the main area of concentration of the leadership grid is a concern for the people and concern for production. Oppositely, the situational leadership spotlight is centered on an interest of the maturity of the leaders’ followers. The basic foundation underlying the Leadership Grid is the ideology that “There is one consistently sound style for exercising leadership across different situations.” (Blake & Mouton, 1981) Conversely, Situational Leadership theorists contend “The exercise of leadership is controlled by the situation. Because no two situations are alike, their conclusion is that there is no ‘one best’ leadership style on which to base practice or behavior.” (Blake & Mouton, 1981) THE LEADERSHIP GRID 9 While both theories consider utilize two common variables in one form or another -- task and the people needed to perform the tasks -- the second difference between the two styles emerges from there. It is the manner in which the two variables are brought together that the two theories vary. The Leadership Grid represents a horizontal axis corresponds to what would be considered as “concern for production” while the vertical axis represents the “concern for people”: According to Blake and Mouton (1981): These variables of leadership are conceptualized as being interdependent. It is impossible to describe the exercise of leadership on one variable without concurrently describing it on the THE LEADERSHIP GRID 10 other, because they are simultaneously interrelated. Any shift in one variable is accompanied by a substantive change in the character of both. In other words, they interact with one another at every point. This theory could almost be equated to Newton’s Law of Motion, but applied to leadership. In other words, where Newton’s Law states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. When applied to the Leadership Grid it can visualized that if there is an action – movement from high to low concern for task – there is an equal and opposite reaction – movement from low to high concern for people. Like the Leadership Grid, Situational Leadership also represents the “task” variable on the horizontal axis. In addition, the vertical axis signifies “relationship”. These two correspond almost identically to “concern for task “and “concern for people” outlined by the Leadership Grid. However, that is where the similarity stops. According to Blake and Mouton (1981): THE LEADERSHIP GRID 11 Conceptually, these two variables of behavior are treated as independent of one another – as though leadership could be described in terms of one variable separately from and without reference to the other. This approach allows any magnitude in one variable to be added to or subtracted from any amount in the other. Based on that statement, one could think of Situational Leadership as flexible and fluid management. A third difference between leadership grid and situational leadership is the inclusion of the behavior of the followers with situational leadership. The leadership grid has been interpreted as being an attitudinal theory focusing attention solely on the leader. Situational leadership adds another dimension. As depicted above, not only is leadership behavior represented within a grid, there is the added element of individual development level shown below. Rather than the two dimensional representation of leadership attitude represented in the Leadership Grid, breadth is added with the inclusion of the maturity level of the follower. It gives focus to the observation of the employees and the abilities of said employees to get the task accomplished. With this supplementary variable, the representation becomes more of a three dimensional model. It demonstrates what leadership behavior will have the higher probability for effectiveness in the given situation with a given follower. Finally, much like the leadership grid with its five predominate leadership categories, situational leadership also describes leadership categories. However, instead of five, they identify four leader behaviors associated with this theory. These behaviors include: 1. S1: High task / low relationship leader behavior. Often referred to as the “telling / directing” behavior, an S1 leader holds the only line of communication. It is through this line of communication that the leader tells the followers exactly what to do, how to do it, and when and where to do it. THE LEADERSHIP GRID 2. S2: High task / high relationship leader behavior. This leadership behavior is 12 typically referred to as a “selling / coaching” behavior. With an S2 leader, communication lines are opened from one-way to two-way channels. Direction is still given, but through communication, the leader is giving support to the follower to get the “buy into” leader decisions. 3. S3: High relationship / low task leader behavior. Unlike the S2 leader, where twoway communication allows for leader decisions to be accepted, an S3 leader uses two-way communication to share in the decision making. Referred to “facilitating / counseling” leadership behavior, an S3 leader no longer has to direct the follower on what to do, but rather becomes a facilitator for the follower to get the task done. 4. S4: Low relationship / low task leader behavior. When a leader has moved to an S4 style of leadership behavior, they have moved to a complete “delegating” approach. A follower that has an S4 leader does so because he is high in ability as well as has great willingness to get the job done and has demonstrated responsibility for directing their own behavior to the satisfaction of the leader. Basically, this leader will take a “hands-off” approach to leadership, only providing support and feedback when needed or requested. With the knowledge of these vast situations, it becomes evident why a situational leader must be able to adapt to their follower. This can be accomplished by altering the degree of task or relationship focus. Unlike the leadership grid, these alternations can be made with little or great impact to the other variable. The differences between the Situational Leadership Theory and Management by Principles, such as the Leadership Grid, can be demonstrated with the following top ten leadership principles. (Blake & Mouton, 1981) THE LEADERSHIP GRID 13 As is evident in the above outline, the two theories have vast differences in practice of basic principles. Conclusion In an attempt to find the “best” leadership style, two theories have seemed to emerge as being the most predominantly favored: The Leadership Grid and Situational Leadership. While there are some that contend that there are similarities between the two, others challenge that the differences are too great to be called equivalent. The basis for both seems to have solid foundation and seem practical in application. The ideology from both could be merged to accomplish the ultimate goal – effective leadership. Integrating the two very well could give THE LEADERSHIP GRID 14 way to a leader that demonstrates all the necessary behaviors needed to influence his followers. Such behaviors that might come from this combination could be a leader that: Sets clear goals Is a model of integrity and fairness Has high expectations Encourages Provides support and recognition Stirs people’s emotions Gets people to look beyond their self-interest Inspires people to reach for the improbable (Blake Mouton Managerial Grid, 2011) Within both of the dominating leadership theories, many of these characteristics reside. A talented leader would be one that could use a hybrid of both theories to reach their definitive objective. THE LEADERSHIP GRID 15 References Blake, R.R., & Mouton, J.S. (1982). Comparative Analysis of Situationalism and 9, 9 Management by Principle. Organizational Dynamics, 20 – 43. Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1981). Management by Grid Principles or Situationalism: Which? Group and Organizational Studies, 439. Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. (1975). An Overview of the Grid. Training & Development Journal, 29(5), 29. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1967). The Managerial Grid In Three Dimensions. Training & Development Journal, 21(1), 2. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Blake Mouton Managerial Grid. (2011). Retrieved July 29, 2011 from Mindtools: http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newLDR_73.htm Brolly, M. (1967). The Managerial Grid. Occupational Psychology, 41(4), 231-237. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Gupta, A. (2009, March 19). Situational Leadership. Retrieved July 29, 2001 from Practical Management: http://practical-management.com/Leadership-Development/Situational-Leadership.html Managerial Grid. (2001). Dictionary of Human Resource Management, 214. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Promoting thought leadership. (n.d.). Retreived July 29, 2011 from Alagse: http://www.alagse.com/leadership/l9.php Robert R Blake and Jane S Mouton: The Managerial Grid (2002) Retrieved July 28, 2011 from http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-1551684/Robert-R-Blake-and-Jane.html